1.Introduction

The process of world economic integration continues to change the spread and use of languages and has a profound impact on the diversity of human languages. The dominant position of the national common language has been highlighted, occupying a major position in cultural communication and daily communication and having a huge social and cultural influence. As a result, local indigenous languages (lengua propia) are constantly under attack, and the importance of their protection and inheritance is becoming increasingly prominent, which further affects the language choice and language attitudes of people in local language communities.

On the basis of the introduction of the native language of Galicia and the linguistic diversity of the region, this paper summarizes the three main ways in which the government of Spain, the autonomous region, and civil society protect the Galician language: legislation, education, and cultural media evaluate the effect of the language protection policies that have been implemented; and examine the changes in the use of the language, the specific situation of inheritance, and social attitudes. On this basis, the paper analyzes the challenges of language protection in Galicia, puts forward some suggestions to improve the existing language protection policy, and looks forward to the future language protection work.

2.Overview of the Galician Language

A Gleanician (Galician/Polemonium) is a Western Ibero-Romance language belonging to the Indo-European family of languages. Galician is now spoken by about 2.4 million people, mainly in the autonomous region of Galicia in northwestern Spain, where it is considered a lingua propia, co-official with Spanish, the first language of the local administration and government, and officially administered by the Royal Academy of Galicia. Galician is also spoken in some border regions of Spain, such as Asturias, Castile, and Leon, as well as among Galician immigrant communities in other parts of Spain, Latin America (including Puerto Rico), the United States, Switzerland, and other parts of Europe.

Although today in the largest city of Galicia, the most common language spoken on a daily basis is Spanish, not Galician (the result of a long process of linguistic transformation), Galician is still the main language spoken in rural areas. The vocabulary of Galician is mainly derived from Latin, although it also contains a moderate number of Germanic and Celtic words, as well as other underlying words and loanwords, and has also received some nouns from Andalusian Arabic, mainly through Spanish.

3.Language Protection Policies in Galicia

3.1.Laws and Measures

Although Galician was officially recognized in Galicia alongside Castilian (also known as Spanish) for the first time during the brief period of the Second Spanish Republic (1931-1939), it endured severe repression and discrimination against its language and culture under Francisco Franco’s centralized military dictatorship following the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939). Throughout Franco's regime (1939-1975), Castilian (Spanish) became the exclusive language used in administration, education, and media, relegating Galician to informal conversations within domestic settings.

However, after Franco’s demise in 1975 and the restoration of democracy along with the enactment of the Spanish Constitution, Article 3 acknowledged Galicia as one of the autonomous regions of Spain, accepting the Galician language as its co-official language [1]. In 1981, Article 5 of the Galician Autonomy Act embraced Galician as the common language of Galicia, further promoting its use across all public domains and at every level. The Act on the Standardization of the Galician Language was approved by the Galician Parliament in 1983, designating Galician as both a language specific to and representative of Galicia while affirming that all individuals from this region possess an inherent right to know and use it. Subsequently, through amendments made until 2008, knowledge of the Galician language became obligatory for all employees within the public sector. Despite challenges, these policies have contributed to the revitalization and promotion of the Galician language.

3.2.Language Policies in the Educational System

The legal and political framework for language policy in Galicia over the past decades has been the 1978 Constitution. Article 2 provides for the autonomy of the national peoples and Article 3 provides that the languages of the national peoples are official languages. Thus, the Galician Autonomy Act (1980) declares Galician as the "language of Galicia," establishes its official status, and obliges the authorities to promote the use of the Galician language "at all levels of public, cultural, and informational life" and to facilitate its dissemination (Art. 5) [2].

In 1983, the Galician Parliament passed the Act on the Standardization of the Galician Language, which covers the language rights of Galicians, the teaching of the Galician language and its presence in the education system and the media. In summary, these provisions aim to safeguard children's right to receive education in their mother tongue, promote the use of the Galician language in education, and ensure that students are not treated unfairly in the educational system due to language differences. Additionally, the educational goal is to enable students to master both Galician and Castilian languages, so they can effectively communicate and express themselves in a multilingual environment.

The Bilingual Education Act regulates the number of classes in which the Galician language is taught, as well as courses in Spanish or Galician, depending on the mother tongue of the student, the requirements of the parents and the means available. The Act also stipulates that anyone wishing to teach the Galician language must apply to the Joint Committee, accompanied by a request from the Parents' Association. This makes the procedure for teaching Galician very cumbersome. In May 1982, therefore, the Galician Council abolished the Dual Grammar to make the procedure more flexible.

A 1995 decree (Decree No. 247/1995) stipulates that at least one third of the subjects should be taught in Galician [3].

In 2004, the Galician Parliament unanimously adopted the Master Plan for the Standardization of the Galician Language, which provides for a 50% increase in the minimum threshold for the use of the Galician language in compulsory education. In 2009, the People's Party won the regional elections in Cilicia. In 2010, Decree No. 79/2010 was issued in the context of the delegitimization of language regulation. The decree states that in pre-school education, teachers will use the students' main mother tongue (Galician), but must take into account the languages of the surrounding region and ensure that the students master another official language of Galicia. In primary and secondary education, the decree provides for the equal use of the two official languages and the gradual inclusion of the third language, English, on an equal basis with the first two. In practice, the multilingualism decree of 2010 means that Spanish is mandatory in most Galician schools in early childhood education, with a 50/50 split between Galician and Spanish in primary, compulsory secondary and Baccalaureate education.

4.Evaluation of Implementation Effects of Protection Policies

4.1.Survey of Language Usage and Inheritance

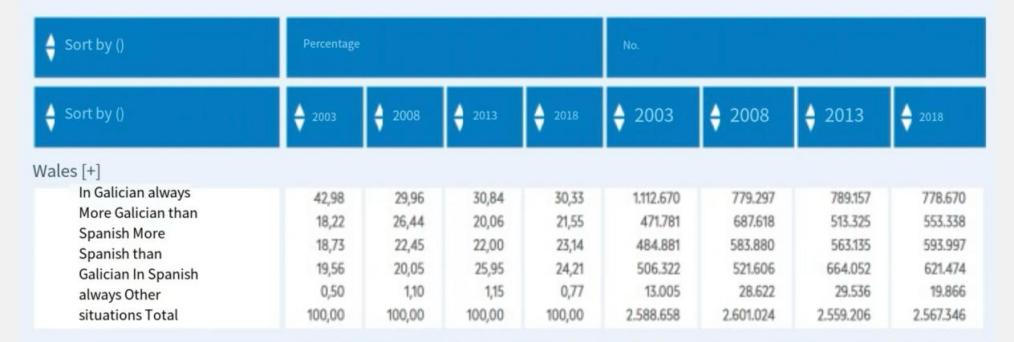

According to the survey data of the Galician Statistics Institute (IGE), in general, the number of people who always speak the Galician language has been declining year by year, accounting for 30.33% in 2018. The number of people who always speak Spanish has been increasing year by year, accounting for 24.21% in 2018, and the number of people who speak more Galician than Spanish is about the same as the number of people who speak more Spanish than Galician, both fluctuating between 18% and 26%.

Figure 1: People according to the language they normally speak, Galicia and other provinces [4].

Figure 1 shows that the survey results of the above four groups of people are roughly balanced in quantity, but very unbalanced in quality: highly polarized distribution in place of residence (urban-non-urban), level of education (low-medium or high), social status (rich-medium), and age (young-old) [5]. For example, in two regions of the Department of La Coruna (Costa da Morte and South-eastern), more than 90% of the population always or mostly speaks Galician, while in the city of Vigo, only 15.2% of the population speaks Galician.

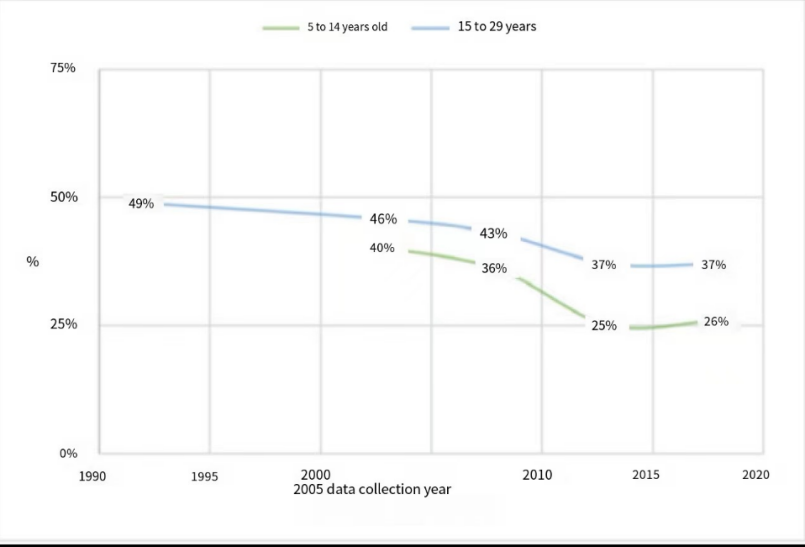

As shown in Figure 2, from 2000 to 2018, the number of Galician speakers in the adolescent population (5-29 years old) showed a significant decline, with the number of Galician speakers in the 5-14 year old population speaking only Galician or other languages falling by 14%, and the number of Galician speakers in the 15-29 year age group falling by 9%.

Figure 2: Evolution of the percentage of galician speakers in the population aged 5 to 14 years and 15 to 29 years. (own creation) [6].

4.2.Analysis of the Correlation between Educational Outcomes and Language Protection

Throughout the 1990s, the use of Galician in teaching gradually increased, reaching about one-third by the end of the decade. Between 2003 and 2008, the proportion of teaching in Galician was more than two-thirds. In 2013, that number dropped to 50% (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Common language used by Ames pupils according to their educational level [7].

In various studies, schools have been identified as an important place to acquire bilingualism in Galician and Spanish as well as foreign languages [8]. In terms of language acquisition, school education not only plays a central role in teaching, but students also engage in a range of social or extracurricular activities (games, sports, training, family activities, etc.) in the campus space that significantly strengthen their language skills.

According to the information provided by teachers, Galician is very common in teaching materials for teachers, students and parents. However, these professionals reported deficiencies in their language training and little knowledge of the language acquisition process or the different modes of language intervention in a bilingual society.

In an analysis of the sociolinguistic geography survey of the Ames area, many primary and secondary school students rated their Spanish proficiency as significantly superior to their Galician proficiency. This concept is formed from the first few years of school to the completion of compulsory education. These results can be extrapolated to Galicia as a whole, especially among Spanish-speaking students living in urban or suburban areas. They found that 25 to 30 percent of schoolchildren had good Spanish skills and poor Galician skills. Moreover, such language characteristics still exist at the end of compulsory education, which is not in line with the equal use status of the two languages expected in the language standardization law.

An analysis of the attitudes towards the Galician language shows that about 30% of primary and secondary school students have a negative or indifferent attitude towards the Galician language. There is a close relationship between students' attitude towards language and their usage of language. In fact, the analysis showed that among high school students who regularly spoke Spanish, those who had the least exposure to Galician expressed the most negative attitudes toward the language. On the other hand, attitudes, values or stereotypes begin to form in primary school and become established in secondary school. It can be seen that adequate exposure and use of Galician at school age play an important role in the relatively disadvantaged language acquisition in a bilingual environment.

5.Challenges

Since the 21st century, the implementation of the Galician language protection policy has not been satisfactory. In 2010, the current Galician government passed a new decree called the Decree on Multilingualism (Decreto de Plurilinguismo (DDP)), which amended the existing policy on language education. According to the Government, the decree is based mainly on a survey of Galician parents to find out what language parents would like to be the language of instruction for their children in pre-school education. Although the new policy purported to ensure the continuation of Galician and Castilian languages in primary and secondary schools, Castilian, the language of instruction it allowed, instead became the mother tongue of children, leading directly to the policy having the exact opposite effect. Since Castilian has always been the most widely spoken language in urban/semi-urban areas, most Galician children tend to be taught Galician in Castilian by their Castilian-speaking parents. Thus, with the implementation of the DDP policy, Castilian automatically became the language of instruction in pre-school education courses in the city. Ultimately, the current policy on the language of education further limits the access of pre-school children in urban/semi-urban areas to the Galician language.

With the arrival of the Bourbon monarchy in Spain in the 18th century, Galician's status, like that of other regional Spanish languages, was greatly reduced, and its social identity gradually weakened. So much so that by the end of the 19th century, it was considered a "bad dialect." Many Galicians dare not even speak to doctors or lawyers in their native language because it is not "elegant.".Some also feel that those who insist on speaking Galician are old-fashioned and not modern enough.

In December 2014, IGE provided macro data showing that the number of teenagers who have never spoken Galician has increased by 17% in the past five years. Government stakeholders, including President Alberto Nunez Feijoo, said in a press release that the current policy situation is pro-Galician and in no way discriminates against the Galician language. He argued that the intergenerational transmission of the Galician language should be in the family, not in the education system, and thus explained why the DDP's policy was detrimental to the spread and preservation of the Galician language. In his view, speaking Galician or Castilian is a matter of personal choice.

Jesus Vazquez Abad, former minister of education in the Galician government, and Dario Villanueva, director of the Real Academia Espanola Villanueva also echoes Alberto Nunez Feho's claim that "freedom of individual language choice in a bilingual society" is the reason for the continuous shift of Galician speakers to Castilian, that is, the decline in the use of Galician is due to the spontaneous choice of Castilian by the population [9].

6.Conclusion

Despite the protection and promotion of the Galician language in law and in social and cultural activities, survey data show that the use of the Galician language is declining year by year, and this trend is even more serious among adolescents. In addition, the attitude of students towards Galician is generally negative, especially among urban students who have fully mastered the language. In addition, some of the overly aggressive conservation policies caused antagonism between classes and social classes, and some members of the social elite saw the implementation of the Galician language policy as imposing the Galician language on them. At the same time, issues of socio-cultural identity and language preference also affect the transmission and use of Galician, and many teenagers choose not to use Galician anymore, but to switch to Castilian, leading to a further decline in the status and use of Galician. The pressure from Castilian and the ongoing language shift put the intergenerational spread of Galician at risk.

The construction of Galician language schools and the opportunity of globalization are the main means we propose. Strengthen the education of the Galician language by supporting the construction of Galician schools, especially in urban areas, in order to promote the inheritance and development of the language. Secondly, Galicia should take advantage of the opportunities of globalization to promote the Galician language as a bridge language between Spanish and Portuguese, strengthen ties with Portugal and other Portuguese-speaking countries, and cooperate in cultural, economic, humanistic and other fields in order to enhance the international status of the Galician language. At the same time, Galicia also needs to actively respond to the challenges posed by globalization, improve the education system, and protect and promote linguistic diversity,so that the Galician language can be fully developed and transmitted in the era of globalization.

References

[1]. Spanish Constitution. Article 3, 1975: 1-55. Retrieved from https://documents.law.yale.edu/sites/default/files/Spain%20-%20Constitution%20of%201978.pdf.

[2]. Xunta de Galicia. Legal Status. [Online Resources] retrieved from https://www.lingua.gal/basic-data-on-galician-language/legal-status.

[3]. Act No.247/1995 Coll. Act on the Parliament of the Czech Republic and on Amendments to Certain Other Acts. Zakony Prolidi. 1995. Retrieved from https://www.zakonyprolidi.cz/cs/1995-247.

[4]. Xunta de Galicia. Basic Data on Galician Language. [Online Resource] retrieved from https://www.lingua.gal/to-know/basic-data-on-galician-language

[5]. Monteagudo, H., Loredo, X., and Vazquez, M. Language and Society in Galicia: The Sociolinguistic Evolution. Royal Galician Academy, 2016: 117-131.

[6]. Seminar on sociolinguistics 19951 and the galician institute of statistics (2003, 2008, 2013, 2018). https://publicacions.academia.gal/

[7]. Benard Odoyo Okal. Benefits of Multilingualism in Education, Universal Journal of Educational Research 2(3): 223-229, 2014

[8]. X. Loredo Gutiérrez, Variables Associated with Grammatical and Lexical Competence in Galician and Spanish of Students in Galicia [J]. Journal of Education Research, 2014, 12 (2), 191-208.

[9]. Nandi, A. Parents as stakeholders: Language management in urban Galician homes [J]. Multilingua, 2018, 37(2), 201-223.

Cite this article

Sun,J. (2025). Local Language Preservation in Galicia, Spain: Status and Challenges. Communications in Humanities Research,65,35-40.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of 3rd International Conference on Interdisciplinary Humanities and Communication Studies

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Spanish Constitution. Article 3, 1975: 1-55. Retrieved from https://documents.law.yale.edu/sites/default/files/Spain%20-%20Constitution%20of%201978.pdf.

[2]. Xunta de Galicia. Legal Status. [Online Resources] retrieved from https://www.lingua.gal/basic-data-on-galician-language/legal-status.

[3]. Act No.247/1995 Coll. Act on the Parliament of the Czech Republic and on Amendments to Certain Other Acts. Zakony Prolidi. 1995. Retrieved from https://www.zakonyprolidi.cz/cs/1995-247.

[4]. Xunta de Galicia. Basic Data on Galician Language. [Online Resource] retrieved from https://www.lingua.gal/to-know/basic-data-on-galician-language

[5]. Monteagudo, H., Loredo, X., and Vazquez, M. Language and Society in Galicia: The Sociolinguistic Evolution. Royal Galician Academy, 2016: 117-131.

[6]. Seminar on sociolinguistics 19951 and the galician institute of statistics (2003, 2008, 2013, 2018). https://publicacions.academia.gal/

[7]. Benard Odoyo Okal. Benefits of Multilingualism in Education, Universal Journal of Educational Research 2(3): 223-229, 2014

[8]. X. Loredo Gutiérrez, Variables Associated with Grammatical and Lexical Competence in Galician and Spanish of Students in Galicia [J]. Journal of Education Research, 2014, 12 (2), 191-208.

[9]. Nandi, A. Parents as stakeholders: Language management in urban Galician homes [J]. Multilingua, 2018, 37(2), 201-223.