1. Introduction

Just like writers write historical records, novels and fictions, filmmakers make documentaries, comedies, or science fictions, artists produce different genre and format of artworks. They serve as a different angle stating a fact objectively, setting a plot or show with satirical meaning, or creating an output based on a whimsical inspiration allowing others who find resonance to enjoy that external benefit. Art could be used to spread religion and culture. We may find different architectural design and painting styles comparing southeast Asian countries versus European countries since they have different ancestral lineage and fundamental culture. Artistic expressions in form of painting and literature reflect the artist’s inner world as well as the historical context [1, 2], for example Qingzhao Li, a female poet in Qing Dynasty China, not only expressed her emotions and values poetically but also contextualized those beautiful words into thematic wash paintings. Art is a decorative interior design referring to the Sistine Chapel Ceiling which leaves people in awe and wonder to both the religious context and Michelangelo’s talent. It is a documentation of historical movements with agitative influence thinking of Liberty Leading the People by Eugene Delacroix 1830. Also, it can establish an attitude and make a stance without necessarily copy a specific movement or book, i.e. Olympia by Edouard Manet 1863. It is a representation of literature, for example Sandro Botticelli visualized The Map of Hell from Dante’s The Divine Comedy. Naturalism and realism paintings are like painters acting as photographers capturing live moments into concrete hard copies. Art exists everywhere from refined bourgeoisie in Paris salons to ordinary countryside factory workers. Artists paint a wide range of objects, and they are willing to emerge themselves with ordinary people, to understand their life and perspective, as well as to empower a painting from a technique-focused and patronized work to an innovative and meaningful artwork. Therefore, the evolution of art form and theme is generally in line with the society’s movement; it documents and expresses tacitly yet powerfully. With, some of the artworks will be heavily spread or strongly banned depending on the topic they portray under which country’s control. Ever since Columbus traveled across the Atlantic Ocean and found the New World, an era of European imperialism had initiated, and racial superiority were coined under the flag of the White Men’s Burden [3]. Human civilization is a collective group; yet, with the distinction over territories, resource allocations, race inferiorities, and nationalism, exploitations and colonialism happened out of different interest parties’ initiatives. The drop of nuclear bombs furthered the degree of damage national conflict could bring to humankind. Thus, after WWII, the Paris Peace Treaty and international organizations like UN, IMF were established to protect individual human rights as well as to guard those “ex-colonial, newly-independent, non-aligned countries” from bullies [4, 5]. Post-war and post-colonial world order is re-shaped, and the shocking impact of imperialism leaves human and society a collective mental illness [6].

2. Literature Review

2.1. Are the artworks created freely or politicized

U.S. Bill of Rights 1789 and Universal Declaration of Human Rights 1948 justifies and protects individual rights in modern nation state and in international arena. States and international organizations emphasize that their power and legitamacy only pertain within the realm of protecting individual’s freedom and rights if individuals’ bond to society’s consensual principles, as stated by John Mill’s On Liberty [7]. The studies on democracy and state’s limited control are so prevalent in the present day, that this highly held approval of democracy has become, to an extent, a totoalitarian doctrine, contested by Gearon F. Liam [8, 9]. This egalitarian society wouldn’t necessarily promote the advancement of society or individuality for they would likely fall into comformity and mediocrity as posed by Nietzsche’s last man theory [10]. Artworks are creative representation of not only artists’ personal expression but also a documentation of historical timeframe. How, then, has the art world evolved especially in parallel with the democratization of western world is the question to be examined and which would lead to the next discussion of fundamental concept of aesthetics.

2.2. Critique of Judgement and Transcendental Idealism

Kant discusses aesthetic judgment, focusing on the nature of beauty and the experience of the sublime. He argues that unlike cognitive judgments (which are based on concepts), aesthetic judgments are based on subjective feelings of pleasure or displeasure. He introduces the concept of "free play" suggesting that in aesthetic judgment, we appreciate beauty for its own sake, without any personal interest [1, 11]. The cognitive process of letting one’s imagination conform to their understanding without any deliberations or constraints would meet a state of transcendence. Freedom is achieved under free play as one may use their creativity and interest boundlessly; their understanding and attention will meet their fantasies instinctively in perfect harmony. Makkreel states that free play would be an activity of conceptual freedom without any empirical evidences to back up or to examine the legitimacy [11]; Ginsborg defended that judgement of beauty is subjective for its own sake referring to Kant’s “autonomy of taste”, highlighting the independence of our judgement of taste no matter whether the aesthetic normativity, or universal validity, exists or not [12, 13]. Interestingly, on Kant’s judgment of fine art, he recounts that artists should create works following fine art’s rule and set the objectivity; yet, he believes “nature gives rule to art” as these gifted genius make “sensible rational ideas of invisible beings” [1, 14]. Anthropologist Gehlen would argue human nature is known for not having any specialized instinct [11-13]. He seeks to reconcile the realms of nature and freedom, arguing that while nature operates according to deterministic laws, human beings possess moral freedom. Aesthetic and teleological judgments play a role in this reconciliation by allowing us to see the world as both determined and as if designed for moral purposes.

2.3. Kandinsky, art is a rhythmic composition from heart

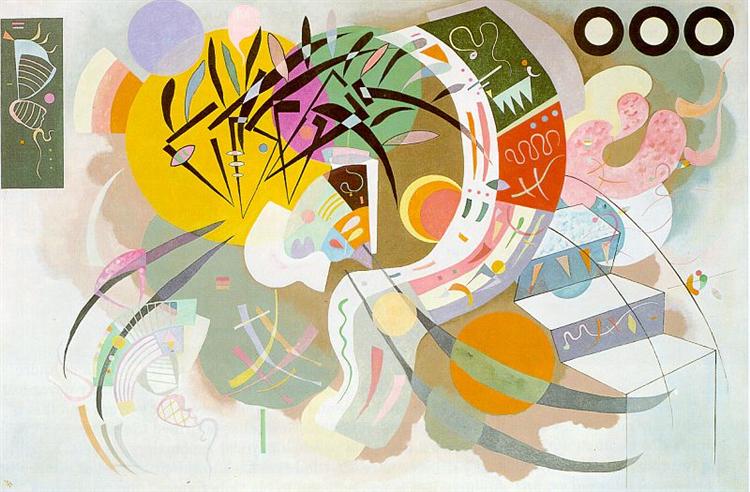

As Vasily Kandinsky stated in Concerning the Spiritual in Art, art focused more on the technical and decorative aspects are lacking in spiritual meaning. He believed artworks are outward representation of artists’ gifted talent. Artists being sentimental and transforming themselves as pure media between the actual works and inner calling are aesthetic because the artwork that composed wholeheartedly aligning with one’s soul is different from the artwork made focusing too much on precision and representation [2]. To Kandinsky, art is like music, and he gives two allegories: artworks based on simple composition is called melodic and complex one called symphonic. The format being performed by the “musician”, or in this case the artist, can be grouped into 1). “Impression”: an artistic performance based on impression; 2). “Improvisation”: a creation out of a spontaneous urge, often time happened naturally and unconsciously; 3). “Composition”: a conscious expression of the inner world that came slowly into maturity. Art is spiritually fulfilling because it expresses ideas and opinions evolved from original school of thoughts in Ancient Rome and Greece all the way through the enlightenment to the contemporary, allowing people to wander in either hope, despairs, contemplations, critiques, discontentment, or inspirations. In his abstract painting Dominant Curve 1936, shown in Figure 1 [15], he used complex layers of form and shapes interwoven ambiguously to create a dynamic and vivid image. His work shows the graphic and coloristic feature more than a genuine figurative reference; the color combination would evoke psychological implications which is subjective to each’s interpretation. Further, the organized lines on the upper left corner, sequenced circles on the upper right corner, as well as the straight line stairs show a compositional clarity between overlapping planes.

Figure 1: Dominant Curve 1936, Vasily Kandinsky [15].

Vasily’s works shift from saturated color combination with thick brushstrokes to geometric planes with chromatic turbulence and sense of depth is a process of him falling further into an abstract expressionist, aligning with his own moral principle of transcendental. Similar artworks are resonating with his abstract style and theoretical allegory of art with music, as we dive into Cubism and Pablo Picasso’s different version of Guitar Player as he plays with dimension, geographical format, compositional depth, and collage with other elements.

3. Case Studies

3.1. Post-WWI German Art in 1930s: finding the transcendental in the harsh reality

The Weimar Republic after WWI and before the reign of Hitler was a time frame of trauma and depression as Germany went through a humiliating war result and the economy was staggering with people readjusting to the shattered society. Albeit, Berlin was prospered with experimental ideas philosophically, scientifically, politically and artistically. Bauhaus was established during this time by Walter Gropius, philosophical and scientific leaders like Hannah Arendt, Martin Heidegger and Albert Einstein were in Germany finishing their studies. The influence of Dada and Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity) propose a denunciation of romantic expressionism and a cling to ruthless realistic depiction of post-war Germany [16]. Living in the turbulent time between WWI and WWII, German artist Wilhelm Heinrich Otto Dix portraits brutal reality of German society in an anguished and dark tone [17]. “I had the feeling that there was a dimension of reality that had not been dealt with in art: the dimension of ugliness” [16-18]. Skin Graft reveals a mad, hyper-sensory, and nightmarish image of a soldier’s distorted face after transplantation surgery. Surprisingly, Dix views battlefield and war as an exciting muse to his artistic creation: “the war was a dreadful thing, but there was something awe-inspiring about it” [19, 20]. The Celebrities (Constellation), one of his etching portfolios, depicts his dark fantasy of four heads symbolizing love, order, fatherland, and dada in one suit and tie body giving a skeptic undertone “the present appeared as an amalgam of distinct, often outmoded traditions vying with one another in the chaos of everyday life” [16-18]. The New Objectivity artists portray the reality unsentimentally and satirically, which still follows Kandinsky’s binding of soul if they are expressing their true opinions, allegorically or factually. Abstract distortion is a trace from expressionism, while collage of different elements/mediums is a character of Cubism. In Kandinsky’s Blue Rider, Yellow, Blue and Red, he used geometric shapes and blurred hues to show an abstract composition without a specific representation. When the artwork loses in form and leans toward expressing an idea, this is also where as Kant has discussed imagination meets with understanding. The understanding of sublime and transcendental character where the physical meets the spiritual. Referring to what Dix said, there is the ugliness in art too. The process of binding the soul to the visualization of either the beauty or the ugliness from expressionism to realism realizes freedom of expression [19, 20]. The search of spiritual and allegorical side as a revolt from realism they follow their urges of the subconscious only to expose them and focus more on the human experience, they offer the world’s transition and a nihilistic attitude as an escape from or a rebellion against reality, leading to a closer look at the counterculture movement in 1960s [21].

3.2. Counterculture in 1960s: art redefined, welcome to a revolutionary social movement and a freedom of consumerism

Guided by the Invisible Hand and being a lender to other countries post WWII, the continued inflation of dollar lead to the broke of U.S. stock market and the Great Depression in 1929. To stimulate household consumption, despite the poor income and high unemployment rate after wars, mass media and marketing strategies designed to trigger purchases take place to incentivize consumers buying products. Art in 1950-60s become more functionalized into commercial and applied art. In But Today We Collect Ads, Smithsons claim fine art retains its vitality through pop art and the later enhances its respectability by the correlation with fine art [22]. Andy Warhol, founder of pop art, show images from consumer goods and mass media messages in bold and straight-forward representation, adding an entertaining mood subjective to his taste of wit and irony [23]. Warhol’s escort and recommendation of African American artist Jean-Michel Basquiat makes Basquiat a well-known young talented; his works are collected with decent pay thanks also to gallery and media’s marketing effort. Marcel Duchamp, leading figure of avant-grade dadaism art further blurred the boundary of refinement with everyday art in his iconoclastic work Fountain 1917. Anti-Vietnam War sentiment and young middle-class hippies’ rebellion against traditional western culture and patriarchy brought marginalized groups’ voice on the table. Citing from Jacques Renciere in Dissensus: On Politics and Aesthetics 1911, “critical art is an art that aims to produce a new perception of the world, and therefore to create a commitment to its transformation” [24]. Protests racial discrimination, fight for women’s rights and equal opportunities for the LGBTQ group let these marginalized group of people be heard and their rights be defended in the Beatles lyrics, the hippies’ lifestyles, the photographies, etc.

4. Future Directions

4.1. Commercial art as an economic output: freedom of expression in a free market

Roman philosopher Paolo Virno discusses the relationship between creativity and today’s economics in an interview with philosopher Sonja Lavaert and sociologist Pascal Gielen in 2009 [25]. Scholars question the aesthetic value from the measurement of economic output in modern day capitalistic perspective. Would modern art both intrinsically and formally show the art of labor power as well as the entire production process? Critics challenge if the post-Fordist art exists as Wittgenstein stated in margin. Do artists (given the premise of creative media art, commercial art and web designers are enlisted as a part of modern artists) have autonomy in the capitalistic society if there is no longer a clear distinction between artists, politics, and means of production. Virno refers Marx idea of formal subsumption that capitalists look after a production cycle and pay for the intelligence each has contributed in this collective cycle to reach surplus. It’s a managerial discretion for the degree of autonomy given to creative positions (advertisement, creative news media, web designers, etc) to yield desired amount of economic output/business intelligence, avoiding the loss of productivity resulted from excessive exploitation. On the other hand, Jack Sagbar from University of Goteberg publishes Artistic Production in the Context of Neoliberalism, Autonomy and Heteronomy Revisited by Means of Infrastructural Critique in PARSE argues that ever since neo-liberalism, the production of art has fundamentally changed from state-supported to a market-oriented model, propelling creators to think in an organizational level with a basic goal of self-sufficiency [26]. The artistic production has taken self-autonomy under the free market of capitalization and gig economy once an artist also needs to take care of education and curation, as Nick Srnicek and Alex Williams have laid out in Inventing the Future. Similar opinions from Wendy Brown and Osborne that artists within this precarious policy-dependent free market become entrepreneurs [27]. Brown criticizes the effect of neo-liberalism as the total economization: “what happens when the practices and principles of speech, deliberation, law, popular sovereignty, participation, education, public goods, and shared power entailed in rule by the people are submitted to economization?”[27]. Not-for-profit art organizations on charitable basis are geared towards commercial success and financially rewarding to the patronage in non-marketized or commodifiable sense [26, 27].

5. Conclusion

The concept of democracy and specifically the freedom of expression is questioned on its application to art. Adopting the Kantian philosophy of aesthetics and transcendental idealism, we found that the definition of beauty and sublime should render to one’s intrinsic disinterested preference and should follow the law of nature. The standard of beauty in artworks is defined by talented genius, who create artworks in a similar fashion as above mentioned way, following one’s inner calling. Art changes from classical to Impressionism and abstract expressionism is a shift from realistic capture of facts to allegorical expression from one’s perception of the outside world. Expressionists like Kandinsky and Mondrian use geometric shapes and dimensional space to stage the art with certain emotions and context, echoing with Kant’s advocacy of natural self-manifestation. Then, we applied this theoretically proven freedom of expression into historical context of 1930s Germany and 1960s U.S. to test if it still holds its truth. Resulted in a conclusion that albeit different political ideologies (totalitarian Nazi government vs. democratic republic U.S. government), art transits freely from being ambiguously abstract to blatantly realistic. Whether in the case of Renaissance, a resurgence to classical art; New Objectivity, an insistence on rationality; or the countercultural movement’s expression against capitalism and longing for peace, art is a crucial medium to document historical context, to make a wit or satirical stance, and to propel the productivity of economy in a capitalistic perspective. The freedom of expression is achieved in art world theoretically and contextually.

References

[1]. Kant, I. (2006). The critique of Aesthetic Judgement. Digireads.Com

[2]. Kandinsky, W. (1910) Concerning the Spiritual in Art. the Floating Press

[3]. Frankenburg, R. (1993). White Women, Race Matters: The Social Construction of Whiteness (1st ed.). Routledge.

[4]. von Lazar, A., Worsley, P. (1966) Review of The Third World, The Journal of Politics,

[5]. Leonardo, Z. (2004). The Color of Supremacy: Beyond the discourse of “white privilege”. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 36 (2), pp137–152.

[6]. Fanon, F., Sartre, J., Farrington, C. (1968) The wretched of the earth (First Evergreen Black Cat Edition). Grove Press, Inc.

[7]. Mill, J. S. (1956). On liberty. Indianapolis, Bobbs-Merrill. Chpt 4, p134-167

[8]. Gearon F. Liam (2010). The Totalitarian Imagination: Religion, Politics, and Education. International Handbook of Inter-Religious Education p933-947

[9]. Riesman, D., By, Continetti, M., Soloveichik, M. Y., Ali, A. H. (2016) The origins of totalitarianism, by Hannah Arendt. Commentary Magazine. https://www.commentary.org/articles/david-riesman/the-origins-of-totalitarianism-by-hannah-arendt/

[10]. Nietzsche, F. (n.d.). Thus Spake Zarathustra. Project Gutenberg. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/1998/1998-h/1998-h.htm

[11]. Makkreel, Rudolf A., 1990, Imagination and Interpretation in Kant: The Hermeneutical Import of the Critique of Judgment, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

[12]. Hannah Ginsborg. (1990a) Kant’s aesthetics and teleology. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/kant-aesthetics/#FreePlayImagUnde

[13]. Hannah Ginsborg, (1990b) Reflective Judgment and Taste, Noûs, 24(1): 63. Reprinted in Ginsborg 2015: essay 6

[14]. Stang, N. F. (2016) Kant’s transcendental idealism. Stanford Encyclopedia ofPhilosophy. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/kant-transcendental-idealism/

[15]. Kandinsky: Dominant Curve, (1936) Solomon R, Guggenheim, New York. Kandinsky | Art Gallery of NSW. (n.d.). https://www.artgallery.nsw.gov.au/whatson/exhibitions/kandinsky/

[16]. Tate. (n.d.). Nine ways artists responded to the first World War. https://www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-britain/aftermath/nine-ways-artists-responded-first-world-war

[17]. Biro, Matthew. (2001). History at a Standstill: Walter Benjamin, Otto Dix, and the Question of Stratigraphy. Res: Anthropology and aesthetics. 40. 153-176

[18]. Consumer Goods, mass media, and popular culture | MoMA. MoMA. (n.d.). https://www.moma.org/collection/terms/pop-art/consumer-goods-massmedia-and-popular-culture

[19]. Bunyan, M. (2016) New Objectivity: Modern German Art in the Weimar Republic:1919-1933 at LACMA. Art Blart, art and cultural memory archive. https://artblart.com/tag/german-art-of-the-1930s/

[20]. Roy, Karcher. Artblart. p16 https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/dix-education.pdf

[21]. Hoggard, L. (2016) The revolutionary artists of the 60s’ colourful counterculture. The Guardian.https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2016/sep/04/revolutionary-artists-60s-counterculture-v-and-a-you-say-you-want-a-revolution

[22]. Smithson, A., Smithson, P. (1998) “But Today We Collect Ads”. In S. Madoff (Ed.), Pop Art: A Critical History. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp3-4. https://doi.org/10.1525/9780520920477-005

[23]. Greenberg, C., Meyer, J. (2023) Pop art. Artforum. https://www.artforum.com/columns/pop-art-169704/

[24]. Rancière, J. (1970). Dissensus: On politics and aesthetics. Internet Archive. https://archive.org/details/dissensusonpolit0000ranc/page/n1/mode/2up

[25]. Virno, P. General intellect. In Lessico Postfordista. Zanini and Fadini (2001). Milan: Feltrinelli.

[26]. Segbars, J. Artistic Production in the Context of Neoliberalism, Autonomy and Heteronomy Revisited by Means of Infrastructural Critique, 2019, PARSE. Issue 9, https://parsejournal.com/article/artistic-production-in-the-context-of-neoliberalism-autonomy-and-heteronomy-revisited-by-means-of-infrastructural-critique/

[27]. Brown, W. Undoing the Demos: Neoliberalism’s Stealth Revolution. (2015) Zone Books. New York

Cite this article

Wang,Z. (2025). The Art World: Freely Innovative or Politicized?. Communications in Humanities Research,56,88-94.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of 3rd International Conference on Interdisciplinary Humanities and Communication Studies

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Kant, I. (2006). The critique of Aesthetic Judgement. Digireads.Com

[2]. Kandinsky, W. (1910) Concerning the Spiritual in Art. the Floating Press

[3]. Frankenburg, R. (1993). White Women, Race Matters: The Social Construction of Whiteness (1st ed.). Routledge.

[4]. von Lazar, A., Worsley, P. (1966) Review of The Third World, The Journal of Politics,

[5]. Leonardo, Z. (2004). The Color of Supremacy: Beyond the discourse of “white privilege”. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 36 (2), pp137–152.

[6]. Fanon, F., Sartre, J., Farrington, C. (1968) The wretched of the earth (First Evergreen Black Cat Edition). Grove Press, Inc.

[7]. Mill, J. S. (1956). On liberty. Indianapolis, Bobbs-Merrill. Chpt 4, p134-167

[8]. Gearon F. Liam (2010). The Totalitarian Imagination: Religion, Politics, and Education. International Handbook of Inter-Religious Education p933-947

[9]. Riesman, D., By, Continetti, M., Soloveichik, M. Y., Ali, A. H. (2016) The origins of totalitarianism, by Hannah Arendt. Commentary Magazine. https://www.commentary.org/articles/david-riesman/the-origins-of-totalitarianism-by-hannah-arendt/

[10]. Nietzsche, F. (n.d.). Thus Spake Zarathustra. Project Gutenberg. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/1998/1998-h/1998-h.htm

[11]. Makkreel, Rudolf A., 1990, Imagination and Interpretation in Kant: The Hermeneutical Import of the Critique of Judgment, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

[12]. Hannah Ginsborg. (1990a) Kant’s aesthetics and teleology. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/kant-aesthetics/#FreePlayImagUnde

[13]. Hannah Ginsborg, (1990b) Reflective Judgment and Taste, Noûs, 24(1): 63. Reprinted in Ginsborg 2015: essay 6

[14]. Stang, N. F. (2016) Kant’s transcendental idealism. Stanford Encyclopedia ofPhilosophy. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/kant-transcendental-idealism/

[15]. Kandinsky: Dominant Curve, (1936) Solomon R, Guggenheim, New York. Kandinsky | Art Gallery of NSW. (n.d.). https://www.artgallery.nsw.gov.au/whatson/exhibitions/kandinsky/

[16]. Tate. (n.d.). Nine ways artists responded to the first World War. https://www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-britain/aftermath/nine-ways-artists-responded-first-world-war

[17]. Biro, Matthew. (2001). History at a Standstill: Walter Benjamin, Otto Dix, and the Question of Stratigraphy. Res: Anthropology and aesthetics. 40. 153-176

[18]. Consumer Goods, mass media, and popular culture | MoMA. MoMA. (n.d.). https://www.moma.org/collection/terms/pop-art/consumer-goods-massmedia-and-popular-culture

[19]. Bunyan, M. (2016) New Objectivity: Modern German Art in the Weimar Republic:1919-1933 at LACMA. Art Blart, art and cultural memory archive. https://artblart.com/tag/german-art-of-the-1930s/

[20]. Roy, Karcher. Artblart. p16 https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/dix-education.pdf

[21]. Hoggard, L. (2016) The revolutionary artists of the 60s’ colourful counterculture. The Guardian.https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2016/sep/04/revolutionary-artists-60s-counterculture-v-and-a-you-say-you-want-a-revolution

[22]. Smithson, A., Smithson, P. (1998) “But Today We Collect Ads”. In S. Madoff (Ed.), Pop Art: A Critical History. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp3-4. https://doi.org/10.1525/9780520920477-005

[23]. Greenberg, C., Meyer, J. (2023) Pop art. Artforum. https://www.artforum.com/columns/pop-art-169704/

[24]. Rancière, J. (1970). Dissensus: On politics and aesthetics. Internet Archive. https://archive.org/details/dissensusonpolit0000ranc/page/n1/mode/2up

[25]. Virno, P. General intellect. In Lessico Postfordista. Zanini and Fadini (2001). Milan: Feltrinelli.

[26]. Segbars, J. Artistic Production in the Context of Neoliberalism, Autonomy and Heteronomy Revisited by Means of Infrastructural Critique, 2019, PARSE. Issue 9, https://parsejournal.com/article/artistic-production-in-the-context-of-neoliberalism-autonomy-and-heteronomy-revisited-by-means-of-infrastructural-critique/

[27]. Brown, W. Undoing the Demos: Neoliberalism’s Stealth Revolution. (2015) Zone Books. New York