1. Introduction

With the development of the internet economy, the presence of "digital nomads" is becoming increasingly prominent. Bloggers, streamers, programmers, freelance writers, and others can theoretically all be categorized as "digital nomads," and they are becoming more visible in daily life. It is estimated that by the end of 2023, the number of digital nomads and potential digital nomads in China will range from 70 million to 100 million people [1]. Additionally, data shows that the domestic flexible labor market has already surpassed 1 trillion yuan [2], highlighting the vast potential of this group.

In recent years, digital nomad communities have sprung up in suburban and rural areas across China, gradually becoming ideal places for digital nomads to work. In response to this trend, many cities and regions are creating and developing digital nomad spaces. For example, Beijing, Guangzhou, Zhejiang, Henan, Jiangxi, Hubei, Shandong, Inner Mongolia, and other areas have established digital nomad spaces of varying scales to attract more young people for work and travel. Notable examples include the 706 Dali Youth Space in Dali Ancient Town, the DNA Digital Nomad Commune in Anji, and the NCC Digital Nomad Community in Huangshan.

There are some distinctions between Chinese and Western digital nomads. Western digital nomads often have an elite profile, primarily consisting of programmers or remote-working white-collar workers. They tend to have a higher income, live globally, and often settle in places with good environments and low living costs. In contrast, digital nomads in China do not necessarily have this elite or professional attribute; their focus is more on the experiential aspect of the lifestyle. In the Chinese context, digital nomadism is not necessarily viewed as a career or way of life in the Western sense. Instead, it is seen as a way for young people to balance their digital lifestyle with career development. From a professional or individual development perspective, digital nomadism in China may not be sustainable.

Therefore, this study aims to focus on the digital nomad group in China, analyzing their unique motivations for mobility, lifestyle management, and philosophy.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Definition of Digital Nomads

The term "digital nomads" originates from the English term "Digital Nomads" and is sometimes referred to as "digital nomads." According to Yao, "digital nomads" is a more fitting term. He argues that "in the transition from 'solid' to 'liquid' society, mobility has become a significant characteristic of modern life. In this social context, digital nomads break the geographical boundaries through the use of digital tools for remote work, allowing them to 'freely roam' between natural, organizational, and mobile spaces" [3]. This perspective gradually replaces the stigmatized meaning of the term "nomad."

The concept of "digital nomads" was first proposed by Makimoto and Manners in their 1977 book Digital Nomads. They defined digital nomads as people who use the internet to find online work and take advantage of the differences in income and living costs between different countries and regions, allowing them can freely switch between work and travel. Many Western scholars have widely accepted this definition. Some scholars argue that digital nomads are professionals who choose extreme forms of mobile work (extreme forms of mobile work) and can balance their love for travel with remote work. This means that digital nomads can leverage geographical arbitrage, earning income from developed countries while living in regions with lower living costs.

Scholars Wang and Wen define digital nomads as "people who use the virtual characteristics of digital technologies to break free from the constraints of specific time and place, engaging in knowledge production, content output, and business management globally through the internet, enjoying autonomy in work while earning an income" [4]. Yao and Yang suggest that digital nomads "are driven by personal interests and hobbies, seeking a dynamic balance between work and leisure, aiming to achieve personal freedom" [5]. A report suggests that most digital nomads are young people, typically from the Global North, represented by the United States, and they travel to regions with lower living costs, engaging primarily in remote digital knowledge work, such as travel bloggers, web designers, and online marketers [6].

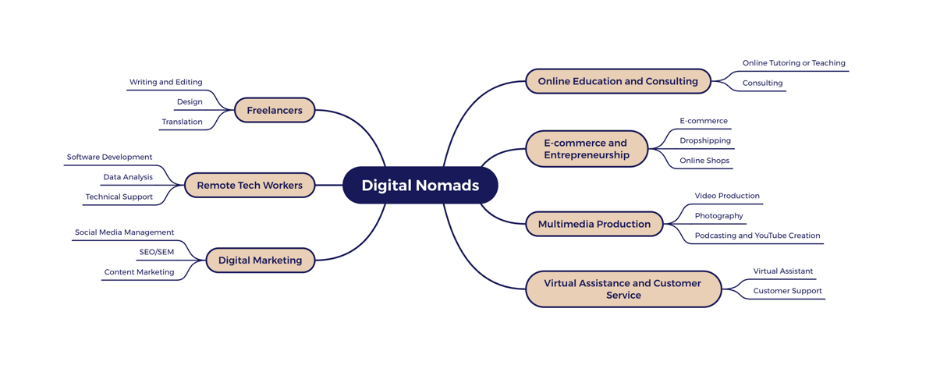

In this study, digital nomads are classified into seven categories, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Categorization of Remote and Digital Professional Services and Specializations.

2.2. The Global Research Landscape of Digital Nomads

Existing research on digital nomads includes studies by Bono, Arrows, and Estaniaxi, who explored the commercialization and romanticization of the digital nomad lifestyle. They mainly discuss how Digital Nomad Lifestyle Promoters (DNLPs) influence other digital nomads' identity work through online narratives, and social media's role in constructing identity in lifestyle professions. They identify four classic archetypes of DNLPs, including motivators, guides, community managers, and influencers [7]. Mancinielli, Germain-More, and others have focused on the interaction between digital nomads and the fluid mobility system. They argue that digital nomads do not simply comply with or resist national governance in their pursuit of freedom. Instead, the mobility system is both an art of governance and living for digital nomads [8]. Reisinger explores how digital nomads seek comprehensive freedom in both work and leisure. She notes that the group mainly comprises young professionals who see career, spatial, and personal freedom as inseparable [9]. Other scholars have analyzed digital nomadic work and its technological applications, identifying four key elements: digital work, gig work, nomadic work, and adventure and global travel. They examine the close connection between these elements and digital technologies [10].

Zhang and Zhan discuss how digital youth, dissatisfied with the social status quo, spontaneously create digital nomadic communities. They see digital nomadism as a dual revolution against modern work systems and consumerism, with the nomadic identity serving as a personalized expression. Digital nomadic communities may, however, be a utopia that is continuously sought and abandoned [11]. Other scholars have explored how digital nomads integrate into rural communities, examining their motivations for returning to their hometowns and how their practices, technologies, and relationships drive rural development and governance [12].

Some scholars have explored establishing digital nomad bases in rural China, using youth mobility to integrate with the rural revitalization strategy, thus enabling rural areas to thrive through mobility and promoting high-quality development [13]. Wu analyzed the weak motivations and strong driving forces of digital nomad mobility. Through research on nomadic youth residing in Qingpu District, Shanghai, Wu proposed that digital nomads should be guided to transition from self-fulfillment to social innovation, thereby contributing to local development [14]. Zhang and Zhang examined the disembedding and re-embedding of digital nomad identities. They argued that the construction of a uniquely Chinese digital nomad identity relies on the process of media-driven manufacturing. Competing interests among different groups continuously appropriate, revise, contest, and negotiate the identity of digital nomads within the media sphere, resulting in a complex, diverse, and distinctively Chinese collective identity [15]. Niu and Chen explored the formation of "media spaces" within the context of nomadism. They suggested that interactions between digital nomads and their spaces follow a four-layered logic, emphasizing that digital nomad communities result from "inter-formation" in media spaces. The concentration of digital nomads in dedicated communities reflects their survival needs, which are shaped by the "nomadization" of social media [16].

Some scholars have also investigated the sense of place among young digital nomads. They noted that "through reproducing local meanings, young nomads construct cultural identities and social significance in their destinations. In the process of 're-territorialization' in different places, they create their imagined sense of 'home'" [17]. The concept of "home" often underpins the establishment of a sense of belonging. Additionally, some scholars have proposed that "platforms like social media nurture and reinforce the identity and collective sense of belonging among digital nomads" [18]. However, existing research on how digital nomads establish a sense of belonging or find a sense of "home" remains scarce.

This study aims to focus on the logic behind the formation of a sense of belonging among digital nomads. The researcher argues that this is not a simple linear process. While digital nomads begin their journey in search of belonging and may indeed experience a sense of "home" in foreign lands, from the perspective of long-term life planning, such nomadic living is only a temporary deviation and cannot form a true and lasting sense of belonging.

3. Research Methodology

This study adopts the method of online ethnography, focusing on the observation and interviews of the digital nomad community on Rednote. Rednote is a social media platform centered around lifestyle sharing. Since its establishment in 2013, it has quickly developed into a leading community-based e-commerce platform in China. Rednote encourages users to share aspects of their lives through posts and short videos, covering areas such as movies, food, and travel. As of now, Rednote has over 300 million monthly active users, with 50% being post-95s and 35% post-00s, making it a platform predominantly used by young people [19].

Online ethnography, developed by Kozinets in the late 1990s, is an adaptation and extension of traditional ethnographic methods. It applies traditional ethnographic techniques, such as observation and interviews, to the virtual world to study online communities, cultures, and behavioral patterns. This method is particularly suitable for studying digital nomads, as they are an active cultural group in online communities and digital environments. On the one hand, digital nomads frequently form or participate in online communities. On the other hand, they share their unique lifestyle and work patterns within these global digital nomad communities, providing a rich material base for research. Applying this method enhances the breadth and depth of the research and allows researchers to conduct effective cultural exploration on a global scale.

This study searched for the keyword "digital nomads" on Rednote and found that related posts have accumulated over 170 million views, with more than 60,000 notes. The tags related to digital nomads include digital nomad communities, remote work, nomadic living, freelance, and "bare resignation." Many bloggers on Rednote share their experiences as digital nomads, and their posts receive many views and comments. For example, the "Nomadic Couple" account primarily shares their life as digital nomads and currently has over 400,000 followers. In addition, the digital nomad communities on the Red Notes have also accumulated 4.175 million views. The main digital nomad communities in China include the DNA Digital Nomad Community in Anji, the DN Yucun Digital Nomad Community, the Thousand Island Lake Digital Nomad Community in Hangzhou, the NCC Community in Dali, and 706 Dali Youth Space. Many Chinese digital nomads also choose to live abroad in places like Bangkok and Chiang Mai in Thailand or Lisbon in Portugal, where the low cost of living and beautiful local culture make them popular destinations. Furthermore, discussions related to digital nomads on Rednote have sparked widespread debates, including topics like digital nomads and rural revitalization, freedom and responsibility among digital nomads, and digital nomads in cultural tourism.

The researcher observed specific digital nomad cases on Rednote and recruited digital nomads for interviews. Heterogeneous sampling was used to ensure that a diverse range of interviewees was covered, reflecting the differences among the studied subjects.

Table 1: Digital Nomad Observation Subjects

ID Name | Followers | Residence Locations | Profession | Duration as digital nomad | Age | Gender |

Nomadic Couple | 203K | Dali,Chengdu,Spain, etc. | Community Manager | 5 years | 90s | couple |

April’s Roaming Diary | 236K | Huizhou | Self-media Blogger, Entrepreneur | 1 year | 27 | Female |

Tommy’s 100 Lifestyles | 31K | Altai, Bali | Self-media Blogger | 4 years | 28 | Male |

A pot | 8K | Ili, Xinjiang | iTravel Group | 1 year | 22 | Male |

Table 2: Digital Nomad Interview Subjects

Interview ID | Residence Locations | Profession | Duration as Digital Nomad | Age | Gender |

S1 | Home | Animal Communication | 4 years | 23 | Female |

S2 | Dali,Anji, Zhejiang | Designer | 3 years | 24 | Female |

S3 | Tanzania, Thailand | E-commerce | 10 years | 35 | Male |

S4 | Home | Self-media, Insurance Broker | 1 year | 29 | Female |

S5 | Indonesia | Chinese Teacher, PPT | 6 months | 24 | Female |

S6 | Quit Digital Nomadism | Cultural Design, Online Shop | 6 months | 23 | Female |

S7 | Singapore | E-commerce Live Streaming | 1 year | 27 | Male |

S8 | Home | Backend Support | 1 year | 30+ | Female |

In the field observations on Rednote, the researcher found that the highly visible bloggers using customized digital nomad tags do not fully meet the characteristics of a digital nomad. Firstly, many of these bloggers constantly travel around the world and do not have a fixed residence, which does not align with the principle of geographical arbitrage. Secondly, some of these bloggers do not engage in online work for economic compensation but label themselves as digital nomads primarily to capitalize on the term's popularity and generate traffic for monetization. This reflects the unique characteristics of the Chinese digital nomad group, which aligns with China's current developmental stage, and in some ways, is an adaptation of the Western definition of digital nomadism.

4. Research Results

4.1. Disembedding: Dual Considerations of Life Welfare and Economy

The initial motivation for digital nomads to leave their long-term residences or work locations is the awakening of personal autonomy. With the rapid development of modern information technology, traditional time and space models have been altered, and people increasingly feel the compression of time and space. Faced with the pressures of career advancement and salary increases, individuals are often trapped in a so-called "involution" of over-competition, which prevents them from forming a sense of work identity and instead leads to physical exhaustion and mental distress. In this social context, the overly competitive society also forces people to contend with the invasion of social media into their private lives and time, with time becoming an invisible control mechanism. People are often required to be online constantly, feeling monitored, controlled, oppressed, and deprived of personal autonomy. In The Scent of Time, Han Byung-chul argues that "the crisis of time today is not the acceleration of time, but its dissolution and atomization. The modern crisis of time arises from a poor experience of time, which causes people to lose their ability to linger or dwell in their lives." People feel their social time is overly consumed, and their private space is severely violated, which has led to an increasing call for the return of individual autonomy. Many people wish to break free from restrictive work environments, leading to the emergence of digital nomads. For example, Rednote blogger @Tommy’s 100 Lifestyles chose to resign from his 400K job in 2023 and became a digital nomad, traveling the world and now has four remote side jobs, including copywriting and blogging. In his posts, he mentions that he became a digital nomad to escape social capital constraints, stop being "a cog in the machine" in a fixed job, and find a lifestyle he truly enjoys [20].

Some professionals choose the digital nomad lifestyle also for economic reasons. Geographical arbitrage becomes their guiding principle. Workers in large cities often do not feel a sense of belonging at home because economic constraints force them to share rented spaces in cramped rooms with limited opportunities to personalize their living space. As a result, their residence becomes only a place to sleep and rest, rather than a home where they can enjoy leisure and entertainment. They can rent larger and more comfortable rooms by choosing more cost-effective travel destinations. For example, the Red Notes blogger @A Pot (一只盆盆)once stayed in a small wooden house in Hemu, Xinjiang, and he mentioned that "even though it was a rented wooden house, it felt like home" as he arranged the room in his comfortable way.

4.2. Independent Lifestyle and Work Approach

4.2.1. Shift in the Mindset of Digital Nomads

As digital nomads pursue freedom, they also accept a certain degree of loneliness or detachment. Digital nomads seek a way of life that allows them to be alone. In fact, they do not want to deal with complex interpersonal relationships in an office setting, as this can increase the risk of isolation, unnecessary social pressure, and interpersonal conflicts. They prefer to focus purely on their work tasks. As one interviewee (S2) stated: "Whether it’s in a dormitory or an office, there are always small groups, and after a while, it leads to anxiety about not fitting in." Another interviewee (S8) added, "I enjoy being alone. I hate pointless socializing."

After a long period of mobility, many digital nomads begin to feel weary of constant movement and relocation. However, for those new to this lifestyle, there is often an initial excitement about mobility, as they look forward to experiencing different ways of life, immersing themselves in various cultural differences, and enjoying the freedom of mobility. As one interviewee (S2) mentioned: "Whenever I think of the office cubicle, with just a computer and a cactus sitting next to it, it feels like even the cactus has lost its soul."

The sense of belonging for digital nomads has shifted from traditional embeddedness in physical communities to a more virtual environment. They increasingly rely on online communities and the recognition of their labor value. Many interviewees expressed that their online work also requires integration into certain virtual networks, and through communication in these online networks, their sense of emptiness or loneliness is alleviated. Additionally, digital nomads often work in various fields, which gives them access to broad online social networks for communicating with clients and marketing products. This, coupled with a continuous cash flow from their work, allows them to receive constant real-time feedback, reinforcing their sense of self-worth and recognition in the market. Their sense of belonging is increasingly tied to their work value rather than familial bonds.

As one interviewee (S2) shared: "At the same time, the work rewards are very high. Before, in traditional jobs, I received a fixed monthly salary. Now, I make money every day, and it feels much less tiring. The income is instant, and I can see my results right away, while also getting feedback from others." Another interviewee (S5) explained: "This sense of stability comes from self-recognition, or the accumulation of money."

4.2.2. Practical Changes in the Digital Nomad Lifestyle

When choosing their travel destinations, digital nomads tend to prioritize the ability to work from home. Even while traveling, they pay more attention to the quality of their living conditions, with economic costs often becoming a secondary concern. Many digital nomads adopt a multi-tasking approach, maintaining a steady and light primary job while continuously expanding their online business to earn additional income. For example, S1, a Chinese teacher in Indonesia, has a relatively relaxed job, allowing time for online business development in addition to her main work. The digital nomadic lifestyle enables greater flexibility in managing time and space. They can focus more on their current experience and better balance work with leisure. While work brings some fatigue, this fatigue is significantly less than that of traditional office jobs. As S6 mentioned: "There is fatigue, but compared to that, I think going to the office every day to clock in is much more tiring."

However, on the other hand, in the face of a constantly changing economic environment, digital nomads are increasingly uncertain about the future direction of their work. The difficulty of generating income has increased compared to the past, and the economic downturn has brought additional pressure and challenges. One interviewee (S4) expressed: "The sense of fatigue has definitely appeared in recent years. This might be related to the economy. In the past, money seemed easier to make, but since the pandemic, things have changed, including my mindset and many other aspects." Another interviewee (S4) explained: "E-commerce is unpredictable. No one can say how long it will last, especially with the rapid development of AI. We’ll have to wait and see what the future holds."

As a result, digital nomads are constantly required to improve their skills to keep up with the evolving trends. In this process, they strengthen their sense of belonging by continually learning and growing. As S8 said: "Once you find a job, it's not a one-time thing. You need to keep learning and face the pressure of being eliminated at any time." S2 added: "As long as you always work on self-improvement and staying active, you won’t feel anxious. If you just rely on your old job, that's when the anxiety sets in."

5. Conclusion

This study primarily explores why digital nomads leave their traditional residences and adopt a more mobile lifestyle, and how they establish a sense of belonging through shifts in both mindset and practice.

First, Chinese digital nomads exhibit unique characteristics that reflect the local context. While geographical arbitrage is an essential principle in traditional definitions of digital nomadism, Chinese digital nomads do not solely make decisions based on economic considerations. They place greater emphasis on a high-quality lifestyle. In their mobile practices, their income often exceeds what they would earn in a fixed job. This paper argues for the distinctiveness of Chinese digital nomads. Future research on digital nomads should consider the cultural and institutional differences across geographic regions, enriching the concept through localization.

Second, this study finds that digital nomads no longer base their sense of belonging on community or family environments defined by kinship. In today’s highly mobile societal structures, young people place their sense of belonging in the value of their work and virtual social connections. In other words, when the market recognizes their labor value, they receive a steady stream of income to meet their living needs, and this sense of self-sufficiency provides them with a stronger sense of security than that offered by kinship relationships.

References

[1]. Yao, J. H. (2024). A cool reflection on the "digital nomad fever". People's Tribune, (07), 86-89.

[2]. iResearch Consulting Group. (2022, September 23). 2022 China flexible employment market research report. iResearch. https://report.iresearch.cn/report/202209/4066.shtml

[3]. Yao, J. H. (2024). Research on digital nomads from the perspective of communication political economy. Journal of Nanjing University (Philosophy, Humanities and Social Sciences), (02), 126-129.

[4]. Wang, Y. L., & Wen, J. (2024). Building autonomy in uncertainty: Reflections on digital nomads' daily labor practices. Zhejiang Academic Journal, (01), 45-54+239. https://doi.org/10.16235/j.cnki.33-1005/c.2024.01.005

[5]. Yao, J. H., & Yang, H. G. (2023). Western digital nomad research review and Chinese implications. China Youth Study, (11), 81-89. https://doi.org/10.19633/j.cnki.11-2579/d.2023.0142.

[6]. “2023 Digital Nomads Report: Nomadism Enters the Mainstream,”MBO Partners (blog), 2023, https://www.mbopartners.com/state-of-independence/digital-nomads/。

[7]. Bonneau, C., Aroles, J., Estagnasie, C., Yao, J. H., & Zhang, Y. L. (2024). The commodification and romanticization of digital nomad lifestyle: Online narratives and professional identity formation. Open Times, (03), 183-198.

[8]. Mancinelli, F., Germann Molz, J., Yao, J. H., & Liu, R. R. (2024). Between compliance and resistance: Digital nomads and frictional mobility regimes. Journal of Jishou University (Social Science Edition), 1-11.

[9]. Reichenberger, I., Yao, J. H., & Xu, S. S. (2024). Digital nomads: Pursuing comprehensive freedom in work and leisure. Trade Union Theoretical Research, (02), 71-79. https://doi.org/10.19434/j.cnki.ghllyj.2024.02.005

[10]. Nash, K., Jalasi, M. H., Sutherland, W., Phillips, G., Yao, J. H., & Xu, S. S. (2023). Beyond "digital nomads": Digital nomadic work and its technological applications. Youth Exploration, (06), 102-110. https://doi.org/10.13583/j.cnki.issn1004-3780.2023.06.009.

[11]. Zhang, P., & Zhan, Y. Y. (2024). Meaning crisis and imagination of neo-tribalism: Research on youth digital nomadic communities. Youth Exploration, (02), 36-48. https://doi.org/10.13583/j.cnki.issn1004-3780.2024.02.004

[12]. Wang, Y. L. (2024). From "wandering" to "settling": Digital nomads' rural embedding and transformation. China Youth Study, (06), 68-77+67. https://doi.org/10.19633/j.cnki.11-2579/d.2024.0078

[13]. Sha, Y. (2024). Mobility as method: Digital nomads in Chinese countryside. Journalism Bimonthly, (04), 28-35+47. https://doi.org/10.15897/j.cnki.cn51-1046/g2.2024.04.001.

[14]. Wu, W. Y. (2024). From self-actualization to social innovation: Guidance for youth digital nomad trends. Youth Studies Journal, (01), 57-62.

[15]. Zhang, W. J., & Zhang, L. K. (2024). Unfinished identity: Mediatized construction and negotiation of Chinese-style digital nomad identity. News and Writing, (07), 76-90.

[16]. Niu, T., & Chen, X. (2024). The generation of "media space" in nomadism: Research on the quadruple logic of digital nomads' spatial production. Journalism Review, (07), 15-30. https://doi.org/10.16057/j.cnki.31-1171/g2.2024.07.001

[17]. Xu, L. L., & Wen, C. Y. (2023). "Where is home?": Research on digital nomads' sense of place in mobile society. China Youth Study, (08), 70-79. https://doi.org/10.19633/j.cnki.11-2579/d.2023.0119

[18]. Sun, Y. K., & Zhou, C. L. (2024). Freedom and identity: Research on digital nomad culture and localized social practices. Intelligent Society Research, (03), 1-17.

[19]. QianGu Data. (2024, April 10). 2024 active user research report (Xiaohongshu platform). https://baijiahao.baidu.com/s?id=1795934648296161044&wfr=spider&for=pc

[20]. Han, B.-C. (2017). The Scent of Time: A Philosophical Essay on the Art of Lingering (D. Steuer, Trans.). Polity Press.

Cite this article

Xu,Y. (2025). How to Define a Home: A Study on the Sense of Belonging among Digital Nomads. Communications in Humanities Research,60,58-65.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Literature, Language, and Culture Development

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Yao, J. H. (2024). A cool reflection on the "digital nomad fever". People's Tribune, (07), 86-89.

[2]. iResearch Consulting Group. (2022, September 23). 2022 China flexible employment market research report. iResearch. https://report.iresearch.cn/report/202209/4066.shtml

[3]. Yao, J. H. (2024). Research on digital nomads from the perspective of communication political economy. Journal of Nanjing University (Philosophy, Humanities and Social Sciences), (02), 126-129.

[4]. Wang, Y. L., & Wen, J. (2024). Building autonomy in uncertainty: Reflections on digital nomads' daily labor practices. Zhejiang Academic Journal, (01), 45-54+239. https://doi.org/10.16235/j.cnki.33-1005/c.2024.01.005

[5]. Yao, J. H., & Yang, H. G. (2023). Western digital nomad research review and Chinese implications. China Youth Study, (11), 81-89. https://doi.org/10.19633/j.cnki.11-2579/d.2023.0142.

[6]. “2023 Digital Nomads Report: Nomadism Enters the Mainstream,”MBO Partners (blog), 2023, https://www.mbopartners.com/state-of-independence/digital-nomads/。

[7]. Bonneau, C., Aroles, J., Estagnasie, C., Yao, J. H., & Zhang, Y. L. (2024). The commodification and romanticization of digital nomad lifestyle: Online narratives and professional identity formation. Open Times, (03), 183-198.

[8]. Mancinelli, F., Germann Molz, J., Yao, J. H., & Liu, R. R. (2024). Between compliance and resistance: Digital nomads and frictional mobility regimes. Journal of Jishou University (Social Science Edition), 1-11.

[9]. Reichenberger, I., Yao, J. H., & Xu, S. S. (2024). Digital nomads: Pursuing comprehensive freedom in work and leisure. Trade Union Theoretical Research, (02), 71-79. https://doi.org/10.19434/j.cnki.ghllyj.2024.02.005

[10]. Nash, K., Jalasi, M. H., Sutherland, W., Phillips, G., Yao, J. H., & Xu, S. S. (2023). Beyond "digital nomads": Digital nomadic work and its technological applications. Youth Exploration, (06), 102-110. https://doi.org/10.13583/j.cnki.issn1004-3780.2023.06.009.

[11]. Zhang, P., & Zhan, Y. Y. (2024). Meaning crisis and imagination of neo-tribalism: Research on youth digital nomadic communities. Youth Exploration, (02), 36-48. https://doi.org/10.13583/j.cnki.issn1004-3780.2024.02.004

[12]. Wang, Y. L. (2024). From "wandering" to "settling": Digital nomads' rural embedding and transformation. China Youth Study, (06), 68-77+67. https://doi.org/10.19633/j.cnki.11-2579/d.2024.0078

[13]. Sha, Y. (2024). Mobility as method: Digital nomads in Chinese countryside. Journalism Bimonthly, (04), 28-35+47. https://doi.org/10.15897/j.cnki.cn51-1046/g2.2024.04.001.

[14]. Wu, W. Y. (2024). From self-actualization to social innovation: Guidance for youth digital nomad trends. Youth Studies Journal, (01), 57-62.

[15]. Zhang, W. J., & Zhang, L. K. (2024). Unfinished identity: Mediatized construction and negotiation of Chinese-style digital nomad identity. News and Writing, (07), 76-90.

[16]. Niu, T., & Chen, X. (2024). The generation of "media space" in nomadism: Research on the quadruple logic of digital nomads' spatial production. Journalism Review, (07), 15-30. https://doi.org/10.16057/j.cnki.31-1171/g2.2024.07.001

[17]. Xu, L. L., & Wen, C. Y. (2023). "Where is home?": Research on digital nomads' sense of place in mobile society. China Youth Study, (08), 70-79. https://doi.org/10.19633/j.cnki.11-2579/d.2023.0119

[18]. Sun, Y. K., & Zhou, C. L. (2024). Freedom and identity: Research on digital nomad culture and localized social practices. Intelligent Society Research, (03), 1-17.

[19]. QianGu Data. (2024, April 10). 2024 active user research report (Xiaohongshu platform). https://baijiahao.baidu.com/s?id=1795934648296161044&wfr=spider&for=pc

[20]. Han, B.-C. (2017). The Scent of Time: A Philosophical Essay on the Art of Lingering (D. Steuer, Trans.). Polity Press.