1. Introduction

Victor Hugo’s Les Misérables has long been recognized as a literary masterpiece, combining powerful narrative techniques with historical commentary to create a rich and multifaceted text. Among the many aspects of Hugo’s work that invite scholarly attention, the June 5, 1832 revolt stands out as a critical historical event that intertwines with the characters’ fates and the broader plot development [1]. The narrative complexity in Hugo’s novel calls for analytical tools that can dissect not only the textual structures but also the underlying thematic and rhetorical dimensions. One such tool is the Segmented Discourse Representation Theory (SDRT), a discourse analysis framework developed by Asher and Lascarides [2] which integrates dynamic semantics with rhetorical structure to explore the interaction between meaning and discourse.

Various linguistic theories such as Systemic Functional Linguistics (SFL), Corpus Linguistics, and Discourse Analysis have been employed, yet their limitations in handling semantic and rhetorical complexities suggest the need for alternative frameworks like Segmented Discourse Representation Theory (SDRT). This theory offers a promising approach to overcoming these limitations by combining discourse structure theory with AI-driven dynamic semantics. It focuses on the rhetorical relations between discourse segments, providing a more refined analysis of text structure and ambiguity. SDRT’s ability to handle semantic vagueness and polysemy makes it particularly suited for analyzing Hugo’s narrative, where metaphors, rhetorical devices, and symbolic meanings often play a central role [3]. One key principle of SDRT is the Right Frontier Constraint (RFC), which limits new discourse units to connecting only with those on the "right frontier" of the discourse structure [4]. While this principle helps maintain coherence, Hugo’s narrative frequently challenges RFC through sudden shifts between historical commentary and symbolic storytelling, creating a layered discourse that resists linear interpretation.

Moreover, Hugo’s intricate narrative structure invites diverse interpretations, aligning with Reader-Response Theory, which emphasizes the role of the reader in constructing meaning. As Hugo intertwines historical digressions, personal fates, and symbolic gestures, the text offers multiple interpretative paths, prompting readers to actively engage with these layers of meaning. This interplay between structure and interpretation makes SDRT particularly valuable for analyzing the implicit connections Hugo draws between historical events and character trajectories.

This study specifically addresses the question: How does Hugo’s integration of historical commentary influence narrative coherence and character fate, and how can SDRT effectively analyze the complex interplay between symbolic and historical layers in Les Misérables. With a particular focus on the June 1832 revolt, this study will analyze Hugo’s integration of historical commentary with narrative. Through both global and micro-level analyses, this research will investigate how discourse structures contribute to the overall thematic and rhetorical coherence of the text. Additionally, the study will engage with ongoing discussions surrounding the RFC in SDRT and examine the theory's application to metaphorical and symbolic interpretations within literature.

By combining a detailed review of linguistic approaches with a specific focus on SDRT, this paper seeks to contribute to the growing body of research on discourse analysis in literary studies, while also addressing some of the theoretical and methodological challenges involved in applying SDRT to complex literary works.

2. Literature review

When applying linguistic theories to literary analysis, various frameworks have been proposed. Systemic Functional Linguistics (SFL) views language as a social semiotic resource, emphasizing social contexts of language use; however, its reliance on specific cultural contexts may limit broader applicability [5-7]. Corpus Linguistics quantitatively analyzes literary texts through keywords and thematic frequency, offering objective insights into text structure, but potentially neglecting nuanced rhetorical and symbolic dimensions due to methodological constraints [8,9]. Discourse Analysis, particularly Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA), highlights ideological implications within social, cultural, and historical contexts, yet struggles with conceptual ambiguities and the challenge of integrating linguistic analysis into traditional literary interpretation frameworks [10,11].

Considering these strengths and limitations, this paper adopts Segmented Discourse Representation Theory (SDRT) as the primary analytical framework. SDRT, established by Asher and Lascarides [2], combines dynamic semantics and rhetorical structure theory to analyze how meanings and structures interact within texts. At the core of SDRT is the concept of rhetorical relations, such as Narration, Elaboration, Contrast, and Explanation, which explicitly define how discourse segments logically connect and build coherent structures beyond the sentence level. This approach makes SDRT particularly adept at handling literary texts characterized by complex thematic relationships, symbolic storytelling, and subtle rhetorical cues [3].

Additionally, SDRT introduces advanced concepts such as "glue logic" and the MDC (Maximization of Discourse Coherence) principle. Glue logic addresses semantic underspecification and allows analysts to determine pragmatically preferred interpretations when multiple meanings coexist within literary texts [12,13]. Meanwhile, the MDC principle emphasizes selecting the most coherent interpretation among competing discourse structures, which significantly benefits analyses involving literary ambiguity and narrative polysemy. Furthermore, SDRT incorporates an expressive logical language known as Lulf, capable of representing nuanced semantic details and capturing complex inter-segment relations. This logical framework provides clarity and precision when modeling intricate discourse structures typical of literary narratives [14].

Moreover, a central principle of SDRT—the Right Frontier Constraint (RFC)—limits new discourse units to attaching to the most recent or structurally relevant units in discourse, thereby ensuring coherence and logical progression [4]. However, this principle faces challenges when analyzing literary texts that frequently employ symbolic, metaphorical, or non-linear narrative structures. For instance, Victor Hugo’s narratives, which interweave historical commentary and symbolic episodes, often deviate from linear discourse attachment patterns prescribed by RFC. These complexities necessitate a flexible approach within SDRT, enabling symbolic elements to form parallel narrative layers and thus maintain interpretive depth while preserving theoretical consistency.

By effectively integrating dynamic semantic modeling, rhetorical relations, and pragmatic principles, SDRT offers distinctive advantages for interpreting Victor Hugo’s sophisticated narrative architecture, capturing how personal fates intertwine with historical symbolism and ideological undercurrents.

3. Methodology

Since this study involves the application of theory, a qualitative research method will be adopted, potentially including textual analysis, case studies, or comparative research. The paper will select several key chapters or themes from the target text and conduct an in-depth analysis using Segmented Discourse Representation Theory (SDRT) to explore how the author uses segmented discourse to express complex emotions and ideas.

Data collection will primarily rely on the text itself. The study will identify significant text excerpts, particularly those that display clear characteristics of historical commentary or literary narrative. SDRT tools and techniques will be employed to analyze these texts, identifying how different discourse segments construct meaning and how these segments interact to enhance the overall effect of the text.

Following data analysis, the findings will be related to the theoretical framework of SDRT, explaining how these findings align with the theory. Additionally, the paper will discuss the significance of these findings in understanding the overall meaning of the target text and how they help in better comprehending the author’s narrative techniques and intentions.

3.1. Global analysis and result

The global analysis will focus on Part Four, Book Ten, "June 5, 1832," primarily examining how Hugo's historical commentary on the riot and revolt is connected to the preceding and following events in the narrative from the structural perspective.

First, this article will present Hugo's historical attitude towards revolts and riots as depicted in the book. Through the analysis of historical events, Hugo distinguishes between revolts and riots: a revolt seeks to restore justice and rights, whereas a riot is often blind and unjust. He asserts that a revolt is always a spiritual phenomenon with a just and noble goal, such as the Parisians' revolt against the Bastille. In contrast, a riot is usually driven by material realities like hunger and poverty. Although its starting point may be justified, its methods and forms are often wrong, leading to unnecessary violence and chaos. He also emphasizes that oppressive and despotic regimes in history often lead to people's resistance, but such resistance is considered a revolt only if it is based on justice and reason; otherwise, it is merely a riot. At the end of this chapter, Hugo defines the June 5, 1832 insurrection as a revolt, not a riot [1].

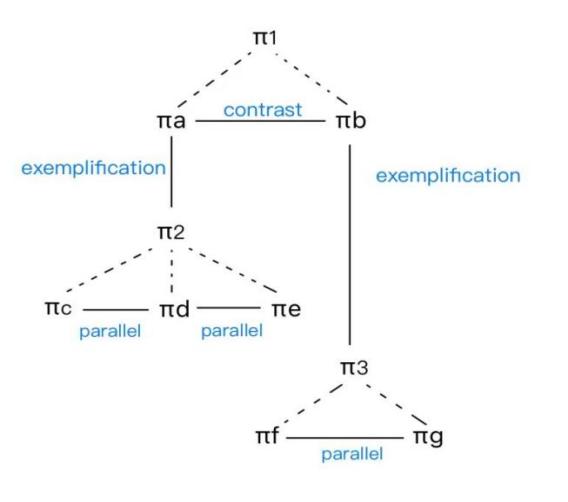

In SDRT, the symbol π is typically used to denote discourse units. Each π represents a specific segment or unit of discourse, which are the fundamental building blocks of discourse structure. These discourse units are used to analyze and describe the coherence relations between different parts of the discourse.

The discussion and narrative surrounding the 1832 revolt will be presented in this manner.

πa: A revolt seeks to restore justice and rights,

πb: While a riot is often blind and unjust.

πc: Marius's thoughts before entering the barricade. He initially fears the harm that civil unrest could bring to society and the nation, but this concern gradually transforms into the belief that "such a war will bring peace [1]."

πd: Enjolras's speech after shooting Le Cabuc. He demands that the insurgents "observe the discipline of the revolt in the eyes of the revolution [1]."

πe: Gavroche builds a barricade using a worker's wheelbarrow, signed "French Republic," reflecting his belief that the resistance he participates in is not a riot against the nation, but a rebellion and revolution pushing the nation forward.

πf: Monsieur Mabeuf is informed by the gardener in a "most ordinary tone" that a "riot" has broken out [1].

πg: The bourgeoisie avoids and disdain the "riot" of the insurgents.

The Figure 1 overall presents a trend of vertical distribution. According to SDRT, the vertical edges of the graph represent subordinating coherence relations, while the horizontal edges represent coordinating coherence relations [3]. Centered around π1, which is Hugo's perspective on riots and revolts, πa and πb unfold vertically downward as two major semantic units subordinate to π1. This step unfolds the concepts of riots and revolts in two completely opposite directions. π2 and π3 serve as collections of exemplifications subordinate to πa and πb, respectively, connecting the abstract historical concepts to the subsequent specific events. Below π2 and π3, specific examples are listed that are in coordinating relationships with each other. The examples of πc, πd, and πe parallel as just revolts, forming a sharp contrast with πf and πg, which parallel as unjust riots.

When the text is converted into an SDRT graph, it becomes apparent that Hugo uses a combination of general statements and specific narratives in the composition of his novel. In the graph, π1, which occupies the top of the subordination chain, represents his overall historical discussion on riots and revolts in the original text. The segments πc-πg, which serve as specific narratives, represent the plot developments surrounding his historical discussion in the original text. This structure allows the historical discussion to lead and summarize the plot narratives. Under this arrangement, the implicit historical trends in the historical discussion also subtly encompass the characters' experiences and fates in the plot narratives.

Figure 1: Global analysis

At the same time, in the narrative of the story, the contrasting attitudes of people from different perspectives towards the revolt echo the distinctions between riots and revolts in the historical discussion. In πa, where a revolt seeks to restore justice and rights, Marius gradually believes that such a war will bring peace, which aligns with the historical argument that revolts are progressive and can lead to social advancement. Enjolras demands that the participants in the revolt adhere to discipline, reflecting the critique of the indiscipline and barbarity of riots in the historical discussion. Gavroche building a barricade with a craftsman's wheelbarrow, signing it "French Republic," similarly demonstrate his belief in the legitimacy of his actions. He sees his actions not as causing chaos but as bringing progress, which aligns with the historical discussion's explanation of the purposes of riots and revolts. In the examples subordinate to πb, which state that riots are blind and unjust actions, the gardener's indifference and misunderstanding of the action reflect the public's blindness due to a lack of social awareness, echoing Hugo's critique in the historical discussion. The repeatedly depicted bourgeoisie, who mock and sneer at "riots", represent their disregard for the legitimacy of such resistance. This misunderstanding echoes Hugo's historical argument that "the true bourgeoisie cannot grasp the subtle differences between revolts and riots; to them, it is all civil disorder, purely rebellion, an act of watchdogs rebelling against their masters [1]."

However, a structural challenge arises when applying SDRT to this passage — the Right Frontier Constraint (RFC). According to RFC, new discourse units can only attach to the most recently introduced unit or its ancestors along the right frontier, ensuring a linear progression of meaning [4]. Yet, in this passage, the symbolic resonance between Hugo’s historical discourse and the characters’ personal convictions causes certain segments to bypass immediate narrative units, forging connections with earlier ideological assertions. For instance, πc — Marius’s evolving belief that "such a war will bring peace" — does not merely follow from the immediate preceding events but resonates with πa’s broader historical justification of revolt, creating a non-linear attachment that challenges RFC.

One effective strategy to resolve the RFC conflict is to treat Hugo’s symbolic language as forming parallel narrative layers. Instead of forcing the symbols into SDRT’s traditional discourse relations, they can be analyzed as metaphorical expansions of the narrative, allowing for more flexibility while preserving SDRT’s core principles. In this interpretation, πa functions as both a historical assertion and a symbolic anchor, guiding the ideological undercurrents that shape individual characters’ choices. This layered structure acknowledges the symbolic dimension as a separate but intertwined narrative layer, mitigating the apparent RFC violation by offering a richer interpretive framework.

Thus, it is evident that Hugo’s arrangement of the plot’s narrative logic is structured around the core themes of his historical discourse segments. His construction of the article’s structure strictly revolves around these theoretical discussions. In SDRT, this is reflected in his prevalent use of subordinating structures when arranging the text. This structure allows the plot to exist as subordinate to the arguments, guided and controlled by the theories. From the perspective of the story itself, the subordination of the plot to the arguments signifies that the characters’ fates and storylines cannot escape the control of historical laws. The development of the plot is ultimately determined by the objective trends of historical development.

By embracing the interpretation of parallel narrative layers, the apparent violation of RFC transforms from a structural flaw into a deliberate narrative choice, reflecting Hugo’s intent to blur the boundaries between history and story, ideology and action. This refined understanding not only resolves the theoretical tension within SDRT but also enriches our reading of Les Misérables, revealing a narrative architecture where personal destinies and historical imperatives converge.

3.2. Micro analysis and result

The micro analysis will focus on the passage from Part Four, Book Twelve, Chapters Seven to Eight, where Enjolras shoots Le Cabuc. In this section, this paper will explore how Hugo, from a rhetorical perspective, places the characters' fates under the control of history.

First, to facilitate the subsequent analysis, this paper will present the specific events of this section. Le Cabuc, suspected to be a member of the Parisian underworld, mingles with the insurgents amid the chaos. While constructing the barricades, he demands that the residents of a nearby house let them in to occupy a strategic position. When they refuse, Le Cabuc shoots and kills an innocent resident. Enjolras then executes Le Cabuc and delivers a speech, calling on the participants of the revolt to adhere to the justice and discipline of the revolution [1].

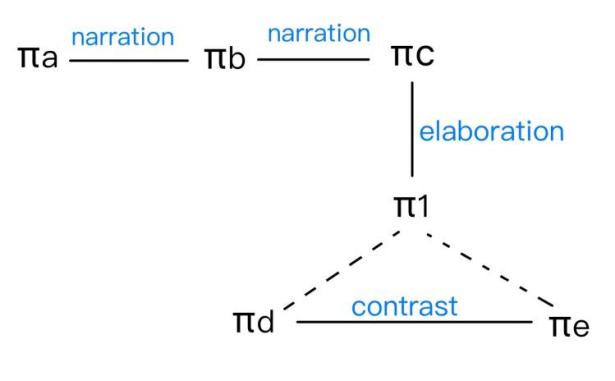

This section will present the discourse structure according to principles of SDRT. Since the purpose of this article is to explore how the destinies of Hugo's characters are controlled by the historical laws depicted by him, although the historical discussion about the riot and revolt will not be included in this chart, it will also be included in the future discussion of this part.

πa: Le Cabuc is a rude drunkard, and no one here knows his true identity.

πb: Le Cabuc argued that they must enter the houses on the street to be safe, and when the residents refused to open the door for him, he shot and killed an innocent resident.

πc: Upon hearing the gunshot, Enjolras executed Le Cabuc.

πd: Enjolras is a delicate twenty-year-old youth, yet authoritative, just, and angry.

πe: Le Cabuc is a broad-shouldered, robust man, but fearful and unable to resist Enjolras' authority [1].

Since this section pertains to the specific narrative, the overall Figure 2 shows a trend of horizontal distribution. According to SDRT theory, narration belongs to the coordinating coherence relations, represented in the graph by the horizontal edges connecting πa-πc. In the original text, the scene of Enjolras executing Le Cabuc is elaborately embellished and described by Hugo, so this part exists as an elaboration subordinate to πc.

Figure 2: Micro analysis

Regarding the specific scene where Enjolras kills Le Cabuc, Hugo employs a significant amount of contrastive rhetoric. Here, the symbolic nature of this rhetorical device is adopted for further analysis.

From the perspective of characters' backgrounds and motivations, Le Cabuc, a member of the gang "Iron Teeth," participates in this revolt purely out of irrationality, aiming solely for destruction and chaos. In contrast, Enjolras, the leader of the student revolutionaries, leads the resistance driven by a desire for reform and progress and with fearless revolutionary enthusiasm. In his previous historical discussions, Hugo mentioned that the motivation for riots is "a latent hostility in the soul for status, life, and fate," while revolts are armed resistance to reclaim one’s rights [1]. Here, the contrasts created in the narrative and those in the historical commentary echo each other. From the perspective of characters’ physical characteristics, Hugo portrays Enjolras as “a delicate twenty-year-old youth,” “pale-faced, with an open collar, disheveled hair, and a face almost feminine,” “clear as crystal”; whereas Le Cabuc is described as “gesticulating and speaking gruffly, with a face like a brutal drunkard,” “a strong, broad-shouldered porter.” As a rhetorical reflection of the earlier historical theory, riots “though powerful, act brutally, although strong, are utterly barbaric,” while the just actions of revolts can be "ideally pure as snow" [1].

Based on these obvious symbolic metaphors, Enjolras represents the just and rational revolt, while Le Cabuc symbolizes the rough and brutal riot. Therefore, Enjolras's act of killing Le Cabuc is imbued with this metaphorical significance: although riots may be powerful and fierce, they ultimately cannot withstand the righteous brilliance of revolts. The irrational and socially detrimental actions of resistance will ultimately fail and be overshadowed by the progress brought about by revolts.

However, when translating this passage into an SDRT graph, a significant structural challenge arises: the symbolic nature of Hugo’s narrative complicates the application of the Right Frontier Constraint (RFC). As previously discussed, RFC mandates that new discourse units attach only to the most recently introduced unit or its right frontier ancestors, ensuring linear discourse progression [4]. Yet, in this passage, the symbolic interplay between Enjolras and Le Cabuc resists straightforward alignment with the historical commentary. The narrative, rich with metaphor and symbolism, blurs the lines between immediate causality and broader ideological undercurrents, challenging the RFC’s constraints.

Additionally, the historical commentary is presented in a summarized form, using concise statements to encapsulate large segments of discourse, while the narrative portion unfolds with greater granularity, each EDU covering relatively little content. This creates a notable disparity in semantic density between the two segments, making it difficult to integrate them into a cohesive diagram. The symbolic layer further complicates the structure, as the connection between Enjolras’s actions and Hugo’s historical reflections lies more in metaphorical resonance than direct causation.

One strategy to address this issue is to interpret the symbolic contrasts between Enjolras and Le Cabuc as forming a parallel narrative layer. Rather than forcing these symbolic actions into SDRT’s traditional discourse relations, they can be viewed as metaphorical reflections of the historical commentary, creating a more flexible interpretive space. In this layered structure, the historical discourse serves as a macro-level ideological framework, while the narrative events unfold as micro-level manifestations of these ideological tensions. The symbolic interplay thus bridges the semantic gap between historical commentary and narrative, subtly guiding the reader toward deeper thematic connections.

Moreover, from the perspective of Reader-Response Theory, Hugo’s symbolic storytelling creates an interpretive space where the reader plays a crucial role in constructing meaning. Initially, the historical commentary appears detached from the immediate actions of Enjolras and Le Cabuc. However, as the reader engages with the text, the symbolic contrasts invite a more active interpretation — one where the reader bridges the gap between history and narrative, ideology and action. The absence of explicit narrative cues compels the reader to discern these connections, transforming the act of reading into a dynamic process of meaning-making.

Overall, Hugo employs a great deal of metaphor in his narration of specific events, and the true imagery these metaphors symbolize aligns with the content of his historical commentary. Therefore, the author's historical commentary can be seen as a guide for the arrangement of subsequent events. The direction of the plot is arranged under the macro guidance of the historical commentary, and the characters' fates ultimately cannot escape the constraints of historical trends. By embracing the notion of parallel narrative layers and recognizing the interpretive space left for the reader, the structural challenges posed by RFC transform into a narrative strategy — one that enriches the complexity of Hugo’s storytelling while inviting deeper reader engagement.

4. Discussion

4.1. Global analysis

In the global analysis, the primary challenge lies in reconciling Hugo’s symbolic language with SDRT’s RFC. Hugo’s narrative structure complicates this principle. The symbolic resonance between historical commentary and personal narratives creates non-linear connections that disrupt the expected sequence of discourse units.

A notable example is the connection between π2 and πa in the graph, where the symbolic interpretation of events, such as the gardener’s indifference representing societal blindness, bypasses intermediate narrative layers to anchor directly onto broader ideological assertions. This deviation from RFC suggests that Hugo’s symbolic discourse operates on a parallel narrative layer, where historical reflections subtly guide character actions and ideological awakenings.

To address this, interpreting these symbolic layers as metaphorical expansions of the narrative offers a pathway to preserve SDRT’s core principles while accommodating Hugo’s complex narrative structure. By allowing symbolic discourse units to attach non-linearly, we acknowledge that the historical discourse isn’t merely background but rather an active force shaping the characters’ destinies. This layered approach transforms the perceived RFC violation into a deliberate narrative strategy that enriches the interplay between history and personal fate.

4.2. Micro analysis

On the micro level, the primary issue is the semantic disconnect between historical commentary and narrative action. The historical reflections are presented as concise ideological statements, while the narrative unfolds through vivid symbolic storytelling. This creates a disparity in semantic density that complicates establishing direct discourse relations in the SDRT framework.

Moreover, the symbolic contrast between Enjolras and Le Cabuc — representing justice versus chaos — operates more as metaphorical reflection than causal progression. This symbolic layer challenges RFC by creating interpretative spaces where the connection between action and ideology is not explicitly stated but inferred by the reader. This ambiguity invites readers to actively engage with the text, constructing meaning between historical commentary and symbolic narrative. Hugo’s storytelling doesn’t enforce a single interpretation but rather creates a dialogue between history and action, where personal narratives become echoes of broader ideological currents.

In this sense, the structural tension posed by RFC is not merely a theoretical obstacle but an essential part of Hugo’s narrative complexity. By embracing parallel narrative layers and acknowledging the reader’s role in meaning-making, the tension between historical inevitability and personal agency becomes a space for interpretive freedom, enriching the text’s depth and resonance.

5. Conclusion

Victor Hugo masterfully crafts long tragic novels, weaving historical commentary into personal narratives to shape the fates of his characters. In Les Misérables, the protagonists appear bound by the ideological currents and historical forces of their time, unable to escape the invisible constraints of fate. Moreover, Hugo’s tendency to intersperse extensive historical reflections within the narrative creates a complex reading experience, where the interplay between history and story can obscure the plot’s progression. This paper applies SDRT to analyze Les Misérables, focusing on how Hugo embeds personal destinies within broader historical movements.

Given the novel’s vast length, this study concentrated on Book Four, Chapter Ten to Book Five, Chapter One, which recounts the barricade revolt of June 5, 1832. Through global analysis, the research examined Hugo’s distinction between riots and revolts, analyzing how this historical discourse subtly guides the narrative trajectory and character fates. The micro analysis focused on the scene of Enjolras’s execution of Le Cabuc, exploring how Hugo employs symbolic contrasts to deepen the ideological undercurrents beneath the immediate action.

The analysis revealed that Hugo’s historical commentary serves as a guiding framework, shaping the story’s structure through parallel and contrasting scenarios. These moments act as exemplifications of historical judgments, subtly influencing narrative events and reinforcing the inevitability of historical forces in shaping personal destinies. Furthermore, Hugo’s frequent use of metaphorical descriptions and symbolic language bridges the gap between historical discourse and narrative action.

The study also revealed significant challenges in applying SDRT to this analysis. In the global analysis, the diagrams often violated the RFC, where newly introduced elements formed non-linear connections with higher-level ideological assertions, bypassing intermediate discourse units. This disruption stemmed from the symbolic meanings embedded in Hugo’s narrative, which operate on a parallel narrative layer rather than adhering strictly to linear discourse progression. To address this, the study proposed interpreting these symbolic elements as metaphorical expansions of the historical discourse and allowing them to attach non-linearly. In the micro analysis, additional challenges arose from the semantic disparity between historical commentary and narrative action. The historical discourse, summarized into concise ideological statements, contrasted sharply with the detailed symbolic storytelling of the narrative, making it difficult to establish direct discourse relations. Furthermore, the conflict between symbolic meaning and literal meaning complicated the diagram’s construction.

These challenges underscore the complexity of applying SDRT to literary texts rich in symbolism and layered meanings. Future research might further examine how SDRT could better accommodate non-linear discourse structures shaped by symbolic language would provide further insights. Integrating perspectives from Reader-Response Theory may also enrich the analysis by considering how readers actively construct meaning when faced with ambiguous narrative structures.

Ultimately, this study highlights SDRT’s potential as a tool for dissecting the interplay between historical commentary and narrative structure in literary texts. While challenges remain, especially concerning RFC and symbolic language, embracing a layered interpretive approach reveals Hugo’s narrative as a rich tapestry where personal fates echo the deeper currents of history, inviting readers to unravel these connections and partake in the meaning-making process.

References

[1]. Hugo, V. (1987). Les Misérables (N. Denny, Trans.). Penguin Classics. (Original work published 1862).

[2]. Asher, N., & Lascarides, A. (2003). Logics of conversation. Cambridge University Press.

[3]. Asher, N. (2017). The Logical Foundations of Discourse Interpretation. In Logic Colloquium'96: Proceedings of the Colloquium held in San Sebastián, Spain, July 9–15, 1996 (Vol. 12, p. 1). Cambridge University Press.

[4]. Danlos, L., & Hankach, P. (2008). Right frontier constraint for discourses in non canonical order. In Proceedings of the Third International Workshop on Constraints in Discourse (CID'2008).

[5]. Eggins, S. (2004). An introduction to systemic functional linguistics. Continuum.

[6]. Martin, J. R. (2016). Meaning matters: A short history of systemic functional linguistics. Word, 62(1), 35-58.

[7]. Rubtcova, M., Pavenkov, O., Khmyrova-Pruel, I., Malinina, T., & Dadianova, I. (2016). Systemic functional linguistics (SFL) as sociolinguistic and sociological conception: Possibilities and limits of theoretical framework.

[8]. Muhsinovna, R. M., & Aminovich, U. A. (2022). The Implementation of Corpus-based Techniques to Analyze Literary Works. Open Access Repository, 8(04), 88-91.

[9]. Biber, D. (1990). Methodological issues regarding corpus-based analyses of linguistic variation. Literary and linguistic computing, 5(4), 257-269.

[10]. Widdowson, H. G. (1995). Discourse analysis: a critical view. Language and literature, 4(3), 157-172.

[11]. Baxter, J. (2010). Discourse-analytic approaches to text and talk. Research methods in linguistics, 117-137.

[12]. Lascarides, A., & Asher, N. (2007). Segmented discourse representation theory: Dynamic semantics with discourse structure. In Computing meaning (pp. 87-124). Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands.

[13]. Schilder, F. (1998). An underspecified segmented discourse representation theory (USDRT). In 36th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and 17th International Conference on Computational Linguistics, Volume 2 (pp. 1188-1192)

[14]. Vieu, L. (2007). On blocking: The rhetorical aspects of content-level discourse relations and their semantics. Aurnague, M., Korta, K. et Larrazabal, JM (eds) Language, Representation and Reasoning. Memorial Volume to Isabel Gómez-Txurruka, 263-282.

Cite this article

Zheng,H. (2025). Symbol, History, and Destiny: Narrative Coherence in Victor Hugo's Les Misérables Through Segmented Discourse Representation Theory. Communications in Humanities Research,60,91-100.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Literature, Language, and Culture Development

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Hugo, V. (1987). Les Misérables (N. Denny, Trans.). Penguin Classics. (Original work published 1862).

[2]. Asher, N., & Lascarides, A. (2003). Logics of conversation. Cambridge University Press.

[3]. Asher, N. (2017). The Logical Foundations of Discourse Interpretation. In Logic Colloquium'96: Proceedings of the Colloquium held in San Sebastián, Spain, July 9–15, 1996 (Vol. 12, p. 1). Cambridge University Press.

[4]. Danlos, L., & Hankach, P. (2008). Right frontier constraint for discourses in non canonical order. In Proceedings of the Third International Workshop on Constraints in Discourse (CID'2008).

[5]. Eggins, S. (2004). An introduction to systemic functional linguistics. Continuum.

[6]. Martin, J. R. (2016). Meaning matters: A short history of systemic functional linguistics. Word, 62(1), 35-58.

[7]. Rubtcova, M., Pavenkov, O., Khmyrova-Pruel, I., Malinina, T., & Dadianova, I. (2016). Systemic functional linguistics (SFL) as sociolinguistic and sociological conception: Possibilities and limits of theoretical framework.

[8]. Muhsinovna, R. M., & Aminovich, U. A. (2022). The Implementation of Corpus-based Techniques to Analyze Literary Works. Open Access Repository, 8(04), 88-91.

[9]. Biber, D. (1990). Methodological issues regarding corpus-based analyses of linguistic variation. Literary and linguistic computing, 5(4), 257-269.

[10]. Widdowson, H. G. (1995). Discourse analysis: a critical view. Language and literature, 4(3), 157-172.

[11]. Baxter, J. (2010). Discourse-analytic approaches to text and talk. Research methods in linguistics, 117-137.

[12]. Lascarides, A., & Asher, N. (2007). Segmented discourse representation theory: Dynamic semantics with discourse structure. In Computing meaning (pp. 87-124). Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands.

[13]. Schilder, F. (1998). An underspecified segmented discourse representation theory (USDRT). In 36th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and 17th International Conference on Computational Linguistics, Volume 2 (pp. 1188-1192)

[14]. Vieu, L. (2007). On blocking: The rhetorical aspects of content-level discourse relations and their semantics. Aurnague, M., Korta, K. et Larrazabal, JM (eds) Language, Representation and Reasoning. Memorial Volume to Isabel Gómez-Txurruka, 263-282.