1. Introduction

1.1. Research background and significance

The 1950s and 1960s, spanning from Stalin’s death through Khrushchev’s rule to the early years of Brezhnev’s leadership, marked a critical turning point in Soviet history and have attracted significant attention from researchers. During this period, the Soviet Union witnessed a transformation from its previously highly restrictive cultural and political-economic system to one of more openness, with a shift from rigidity to “thawing.” The Soviet animation industry was one of the beneficiaries of these policy changes, as the reform of cultural policies and the significant advancements in Soviet film theory and technology during the early 20th century played a role in the flourishing and transformation of Soviet animation. In 1954, the “Animation Production Plan” was introduced. According to the third issue of Soviet Cinema Art in 1954, the Ministry of Culture of the Soviet Union approved a “resolution to expand the production plan of the animation film joint production studio,” with twenty films slated for production in that year—an increase of about ten films compared to the previous year. Besides the rise in quantity, another notable trend during this transitional period in the animation industry was the nationalized style.

However, the desire to lead the people of various nations through the political ideals of Soviet spirit also led, to some extent, to a lack of self-identity and spiritual belonging for the Soviet people. Furthermore, the Russians, with their long history of “Europeanization,” were also striving to restore the cultural values of their own ethnicity. Politically, there was an active exploration of cultural reawakening, particularly in the context of competition with the capitalist bloc, placing greater emphasis on cultural industries with Soviet characteristics to enhance cultural soft power.

This paper explores the national characteristics of Soviet animation from 1953 to 1960, examining its visual presentation, creative concepts, and stylistic development through representative works and key figures. It also investigates the aesthetic motivations and international influences shaping Soviet animation, offering insights into the nationalization of China’s contemporary animation industry.

Focusing on three emblematic Soviet animated films—The Twelve Brothers-Months, Big Troubles, and Man in A Frame—analyzing their creation background, visual presentation, and stylistic construction. Through the analysis of these works, the paper will offer new perspectives on the formation and evolution of nationalized styles in Soviet animation and explore their deeper artistic influences.

2. Research content and methodology

2.1. Research content

This paper explores the evolution of Soviet animation in the 1950s and 1960s, examining its historical and political context, ethnic cultural influences, and theoretical foundations through case studies. It is structured into three chapters: the first traces the transition of Soviet animation into its golden age from the late 1950s to the 1960s, analyzing its development through political, cultural, and artistic perspectives; the second provides an iconographic analysis of two representative animated films; and the third expands on this analysis through a comparative study of works from Soviet Film Production Studios, offering further iconographic interpretation of the selected films.

2.2. Research methodology

The primary research method used in this paper is iconography. Through the analysis of visual elements in animated films, this method aims to interpret the cultural, historical, social, and symbolic meanings behind the imagery. Additionally, the paper employs methods such as collection and inductive analysis, literature review and textual analysis, and interdisciplinary research. A substantial amount of animated film data will be collected and reviewed, including related film reviews and background information on the filmmakers. The analysis focuses on the audiovisual material from an iconographic perspective, using individual case studies to derive general conclusions.

3. Literature review

While Soviet animation remains a niche scholarly focus globally, foundational contributions exist. Chinese scholarship predominantly examines its developmental history and cultural symbolism, yet lacks rigorous analysis through iconographic, artistic, or stylistic lenses. Seminal works like Duan Jia’s World History of Animated Film and Yu Weizheng’s Notes for Animators provide valuable historical frameworks, while translated volumes such as History of Soviet Film (China Film Publishing House) and Animation Art History of the World (Central Compilation and Translation Bureau) offer broad chronological surveys. However, their expansive scopes often sacrifice granularity—a gap this paper addresses by analyzing three landmark films to dissect Soviet animation’s nationalistic stylization.

International scholarship demonstrates greater thematic diversity. Works like The Animation Studio: The World History of Animation and Orlando Figes’ Natasha’s Dance: A Cultural History of Russia contextualize Russian animation within broader cultural trajectories. Specialized studies, such as Russian Animation of the 1960s and the Khrushchev Thaw, scrutinize policy impacts on creative practices, while Realization of “Russian Character” in Soviet Animation decodes nationalist iconography through character design. Surrealist influences under Soviet censorship are explored in The Discreet Charm of Surrealism in Eastern European Animation, and East Slavic Mythology as Content for the Russian Animation Industry links folklore revival to state cultural agendas. Collectively, these works inform this study’s methodology, bridging historiographical breadth with targeted formal analysis.

4. Main text

4.1. “Thaw” and comprehensive development in the 1950s and 1960s

The development of Soviet animation in the 1950s and 1960s was deeply influenced by political, cultural, and technological changes. During this period, the political environment and social atmosphere in the Soviet Union provided unique conditions for animation creation, with both strong domestic momentum and external stimuli from international artistic movements.

Under Stalin’s rule, the Soviet cultural system was highly centralized, subjecting all artistic forms, including animation, to strict political oversight. Socialist realism was institutionalized as the official artistic doctrine, requiring works to serve socialist construction, promote collectivist ideals, and glorify revolutionary values. While largely devoid of critical or experimental elements, animation from this period carried strong political undertones and reflected contemporary social realities.

Following Stalin’s death, Khrushchev’s rise to power ushered in the “Thaw” period, easing ideological constraints and expanding artistic freedom. His policies of mass amnesty and denunciation of the personality cult fostered a more open creative environment, allowing animation to break free from rigid state control. This shift encouraged greater thematic and stylistic diversity, particularly in social satire and political critique. By the early 1960s, Soviet animation underwent a profound transformation, as realist aesthetics and naturalistic designs gave way to a more stylized cartoon approach, paving the way for experimental animation [1].

Moreover, the Soviet Union’s diverse cultural landscape significantly influenced its animation industry. As a multi-ethnic state, it integrated a wide range of artistic traditions, blending Russian heritage, religious influences, and Soviet ideology. This fusion created a distinctive artistic environment, offering animators a rich source of creative inspiration. The nation’s complex ethnic composition fostered a variety of artistic styles and narrative approaches, ensuring that Soviet animation transcended a singular aesthetic framework.

On the technological front, Soviet animation inherited traditional techniques while also embracing external innovations. Since the 1930s, Soviet animation had borrowed from montage techniques, a method introduced by film master Sergei Eisenstein. Initially used in film narrative, this technique was later adopted in animation creation. The application of montage made the narrative of animation more rhythmic and impactful, extending beyond mere entertainment to serve political propaganda as well. Moreover, the influence of socialist realism on animation creation meant that many works focused on socialist ideals. While these works rarely reflected the critical or fantastical elements seen in Western animation, they were characterized by a strong sense of the era in their integration of form and content.

With technological advancements, Soviet animation refined its production methods. By the late 1950s, international techniques, particularly from Disney, enhanced character fluidity and background design. The adoption of cel animation improved precision, continuity, and visual quality, while the shift from stop-motion to 2D animation increased creative flexibility and complexity.

The creative process also evolved from individual efforts to collective production. The establishment of Soyuzmultfilm marked a new era of professionalism, gathering top talent and providing extensive resources. Soviet animation also absorbed global influences, incorporating advanced techniques from the U.S. and France while the Zagreb School encouraged expressive, experimental approaches. Romanticism and avant-garde movements further drove artistic innovation, fostering bold stylistic exploration.

In conclusion, the development of Soviet animation in the 1950s and 1960s was shaped by political, cultural, technological, and artistic forces. While adhering to socialist ideology, it embraced greater artistic diversity and technical sophistication. Political shifts allowed more creative freedom, while international influences enriched visual expression and narrative depth, forming a unique animation language and artistic identity.

4.2. Stylized presentation of animated imagery

Big Troubles is a delightful satirical animation created by the Brumberg sisters. The film, told from the perspective of a young girl, uses a childlike drawing style to depict her family. Her father is corrupt and accepts bribes, her brother is foolish and spends his days partying, and her sister is uneducated, only dreaming of marrying into wealth. The text off-screen tells the story of the little girl as she repeats phrases she doesn’t understand, and these expressions are drawn literally according to how she imagines them. In the film, the narrator is both a character in the story and its creator, which emphasizes the film’s layered structure. In this structure, the world that a child sees contrasts dramatically with the real world she inhabits, and this juxtaposition is key to the film’s success [2].

Figure 1: A graphic representation of the idiom “whip vodka in a hurry” from Big Trouble

As shown in the image above, “whip vodka in a hurry” is a Russian idiomatic expression meaning “to get drunk,” but in the animation, the little girl doesn’t understand the idiom, so she depicts it literally as “riding vodka at full speed.” The combination of the visual image and the childlike voice-over commentary contrasts the literal meaning understood by the child with the metaphorical meaning understood by adults, highlighting the satirical nature of the piece [2].

In terms of artistic expression, this animation does not follow the naturalistic style of realism or the Disney style. Instead, it draws inspiration from the Constructivist style, which originated in architectural design. The Constructivist style belongs to the “non-objective art” proposed by Russian artist Wassily Kandinsky, which does not refer to natural or real-world objects in painting. Rather, it explores the inherent qualities of art such as color, tone, weight, texture, shape, movement, spatial awareness, and the balance of composition, aiming to construct art for a new era and a new order. This aligns with the political environment in Russia at the time.

At the same time, the materials used for the artwork, such as markers and watercolors, which are commonly seen in children’s drawings, are retained, with brushstrokes visible, making the piece appear more authentic. As shown in the image above, the watercolor’s uneven wet streaks are kept intact.

(a) (b)

Figure 2: (a) Character appearance from Big Trouble (b) watercolor hand-painted marks in the drawing

In the image above, the animation exaggerates the physical features of the five family members through simple shapes and bold contrasting colors. This creates distinct and clear character representations, allowing the audience to form certain impressions of the characters’ personalities based on their appearance.

It is also worth mentioning the way characters move in this animation. Since it is presented through flat, childlike drawings, perspective is rarely used. The characters’ movements are flattened, as seen in the image above where the girl’s brother walks sideways. This creates a humorous and exaggerated effect, reinforcing the satirical tone, which fits the film’s setting.

(a) (b)

Figure 3: (a) Shows that the characters in “Big Trouble” do not walk in a realistic way

(b) characters in Big Trouble move a lot

The scenes and characters in this animation are relatively simple but not rigid or monotonous. Apart from the engaging plot and novel expression methods, the rapid pace, exaggerated and unconventional movements, and creative scene transitions further enhance the expressiveness of the piece. For instance, in the image below, the teacher pulling the brother’s ear is exaggerated, intensifying the action of building up and releasing tension. The teacher’s movements are also depicted as unbalanced and irregular, highlighting the expressiveness.

Overall, this work presents a fresh and unique mode of expression. Its subject matter, different from the glorification of socialism and collectivism of the old era, directly confronts reality with sharp satire. It opens the door to a new style and has had a significant impact on the films of the 1960s [2].

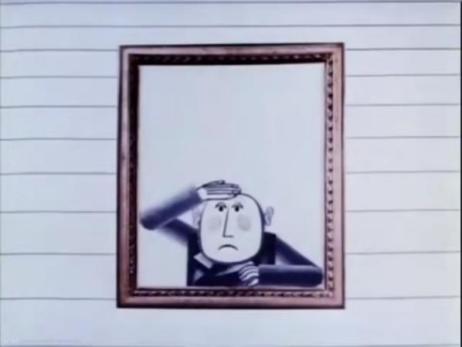

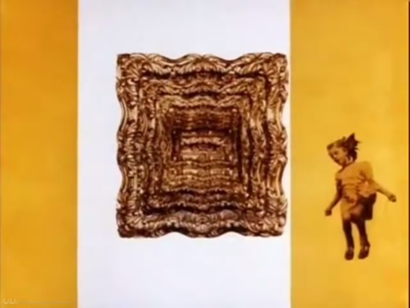

In contrast, Man in a Frame (1966), an animation created by Fyodor Khitruk, tells the story of a young official who, upon entering the political arena, nails a frame around himself. As he advances in his career through flattery, rejecting love, and sacrificing his life, the frame around him grows larger, thicker, and more ornate, until it ultimately consumes him.

his work is a sharp satire of bureaucracy, using symbolic visuals to enhance its critique. The characters, reduced to simple geometric shapes, resemble cogs in the system, prioritizing career advancement over real human experience, highlighting bureaucratic rigidity and indifference.

The frame symbolizes ideological constraints, power, and status, with its position and ornamentation reflecting official rank. Occasional flashes of realistic imagery, such as a girl skipping rope, contrast the bureaucratic monotony, symbolizing childhood innocence and life beyond work. The film’s masterful use of symbolism reinforces its critique of the dehumanizing effects of the system.

(a) (b) (c)

Figure 4: (a): Character shape made of flat geometric shapes (b): montage of girl jumping rope (c): montage of parent-child relationship

In terms of artistic style and expression techniques, the work does not use voice-over dialogues; instead, the characters’ speech is presented in written form on the screen. The rigid, heavy printed text reflects the impotence of human speech and the authoritative power of official documents. The scenes with the frame appear like patterns printed on lined notebook paper, possessing the aesthetic of prints, yet also conveying the cold and rigid nature of the bureaucratic system. These scenes also allow the inherent compositional strengths of Soviet art to be better showcased.

(a) (b)

Figure 5: (a) Dialogue written for print (b) bureaucrats in frames

The montage editing technique and the way the camera switches between shots allow the characters’ real lives, work, and inner worlds to be simultaneously presented to the audience, expanding the amount of information in the film. The montage in this film alternates with comic and realistic styles, which seems to be influenced by collage art. These expression techniques enhance the expressiveness of the work.

Figure 6: The frame engulfs the protagonist

Overall, the work’s mode of expression is highly symbolic. Different images symbolize different states of life, with the intuitive images downplaying dialogue, actions, scenes, and other narrative elements, thereby strengthening the core of the story and making the theme more prominent.

4.3. The nationalization exploration of animation imagery

Unlike the two films previously introduced, the next film, The Twelve Brothers-Months, is a relatively typical joint production by animation film studios. Its subject matter, production method, theme, and aesthetic style can be seen as representative of Soviet animated films from the 1950s. At the time, the cultural policy assigned animation the main task of educating children, spreading knowledge, returning to tradition, exploring national culture, and conveying the values promoted by socialism.

The Twelve Brothers-Months was adapted by Ivan Ivanov-Vano from Samuil Marshak’s children’s fairy tale drama of the same name, and it was released in 1956. The story tells of a girl, mistreated by her wicked stepmother and stepsister, who is forced to search for snowdrops that bloom only in April during the harsh winter. Ultimately, she wins the help of the twelve month deities due to her virtuous character.

From the perspective of subject matter, the original work is based on folk legends, where, at the New Year, one has the opportunity to meet the twelve month brothers and experience all twelve months in a single moment. The story focuses on the different treatments two girls receive after encountering the twelve month brothers. Marshak’s children’s play adaptation introduced the character of a petulant little queen to intensify the dramatic nature of the story. The animated version further incorporates the admiration of the character April for the little girl, making the role of April and others more prominent.

On the level of national culture, the film integrates many traditional Russian mythological elements. The Russian people have long practiced polytheism. Although the concept of “twelve gods of the seasons” is not explicitly recorded in traditional Slavic mythology and folklore, there are similar worships of deities or spirits. In the animation, the twelve deities not only represent different months but also symbolize the natural phenomena and changes in flora and fauna according to Slavic customs. While the animation maintains its playful nature, it also carries a strong educational undertone, introducing audiences to knowledge related to the seasons, farming, and other topics associated with Russian folklore.

For example, in the opening scene of the animation, the rabbit and squirrel are playing a traditional Slavic game, similar to “hide and seek,” where one person in the front tries to catch the people running out from the back of each team and prevent them from holding hands. The losers become the new “fire,” and the other two return to the team, thus passing the “fire.” Originally, this was a game for expressing affection between men and women, held in early spring, symbolizing the welcoming of spring.

(a) (b)

Figure 7: (a) Twelve-month deity roasting a bonfire (b) rabbit and squirrel playing traditional Slavic games

Another When the female protagonist encounters the twelve deities in the forest, they gather around a campfire, which not only provides warmth but also symbolizes Slavic spring rituals. These rituals include lighting bonfires to welcome Yarilo, the deity of spring and fertility, and burning effigies of Marzanna, representing winter and death, marking the seasonal transition in Slavic tradition.

Production-wise, the film showcases distinct Disneyan influences through its anthropomorphic fauna, elastic character movements, and dynamic squash-and-stretch techniques. The juxtaposition of lush oil-painted naturalistic backdrops against stylized 2D figures exemplifies a hybrid aesthetic—Western technical frameworks reinterpreted through Soviet visual idioms. This synthesis highlights Soviet animation’s ability to assimilate Western methods while preserving its unique artistic identity.

In terms of artistic style, The Twelve Brothers-Months differs from the similarly produced A Red Flower in the Soviet Film Production Studios, which is known for its meticulous and lavish scene designs and pursuit of large depth of field and long shots. In The Twelve Brothers-Months, the majority of the shots use medium and close-up framing, and the scene designs appear somewhat flattened. This choice of framing helps concentrate the viewer’s attention on the story, facilitates character portrayal, and advances the plot, though it does make the visuals feel somewhat lacking in spatial depth.

(a) (b)

Figure 8: Comparison of scene design between Twelve Months and One Little Red Flower (a) from Twelve Months and (b) from One Little Red Flower

As seen in the images: Figure 1 shows a still from The Twelve Brothers-Months, and Figure 2 shows a still from A Red Flower.

Overall, the film expresses admiration for the working people through the support and praise of the twelve deities for the protagonist and the punishment of the oppressive stepmother, stepsister, and queen. Through the folk fable genre, it conveys the central ideas in line with the mainstream values of the time, serving an educational purpose. It also reflects that during the early years of the “thaw,” outstanding animated films were still government-led productions, thus limiting them in various ways.

Through the analysis of The Twelve Brothers-Months, the differences in style and themes between the “thaw” period and earlier works become apparent. After the “thaw,” Soviet animation, particularly in Big Troubles and Man in A Frame, gradually shifted towards a focus on real-life issues, presenting deeper reflections on societal, political, and personal dilemmas.The Russian people in the twentieth century experienced an extraordinary series of events. Two revolutions, two disastrous wars, industrialization and collectivization, and the Stalinist Terror changed the lives of millions of people. As we look back on this bloody recent history, we wonder how those who experienced both excitement and fear saw and understood the changes that were taking place around them[3]. The creators, a new generation of intellectuals, the so-called “progressive social activists,” emerged during this period. They embraced social democracy and the de-Stalinization of society, attitudes they maintained for decades[4].

Figure 9: Kolya doing jazz in Big Trouble

Kapa, the protagonist’s sister, embodies a shallow materialism, aspiring to marry a wealthy man but failing repeatedly—a trait condemned by traditional Soviet values. The film satirizes systemic corruption through figures such as the girl’s bureaucrat father and bribed officials, critiquing both institutional flaws and the younger generation’s increasing materialism and hedonism under Western capitalist influence. It sparked significant debate upon release and continues to provoke societal reflection.

Man in A Frame, released during the late“thaw” and early Brezhnev era, coincided with greater artistic freedom, fostering the rise of experimental animation. Influenced by symbolism, minimalism, abstract expressionism, and the Zagreb School, this period saw a diversification of aesthetic and creative approaches. The film, targeting an adult audience, critiques bureaucratic rigidity not only through institutional flaws but also by examining the psychological deterioration of officials. The protagonist, consumed by ambition and power, isolates himself, becoming indifferent to life’s beauty and the people’s concerns. This reflects the Russian concept of byt (daily routine and stagnation) versus bytie (spiritual existence), a central theme in Russian intellectual thought [5].

A comparative analysis of these films reveals that Soviet animation from the mid-1950s to the 1960s was deeply rooted in national identity while developing a distinct artistic style. By integrating socialist values with evolving historical contexts, these works embodied national characteristics through their themes, aesthetics, and ideological perspectives. Their synthesis of folk traditions and socialist realism offers valuable insights for contemporary national animation.

5. Conclusion

In the 1950s and 1960s, Soviet animation underwent a transformation from a style clearly oriented toward naturalism and ideological “socialist realism” to a gradual awakening of individual consciousness and personal style. In this process, the presentation of national identity was reflected not only in the traditional patterns, costume symbols, natural imagery, and distinctive constructivist style of the animation but also in the values conveyed and the reflection of social realities. This paper draws the above conclusions through the analysis of animation case studies, but there are still many shortcomings. This paper does not involve a large amount of data, and the sample size is insufficient. Additionally, Chinese animation was not included as part of the comparison. The national visual presentation in Soviet animation and the experiences and explorations of animators remain topics that can offer numerous insights for contemporary animation creation and deserve further in-depth exploration and research.

References

[1]. Gu Qijun." The Evolution of Modern Animation Aesthetics in Soviet Russia." Film Arts 6(2018):9.

[2]. Pontieri, Laura. Russian Animation of the 1960s and the Khrushchev Thaw, Yale University, United States -- Connecticut, 2006. ProQuest,https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/russian-animation-1960s-khrushchev-thaw/docview/304980452/se-2.

[3]. Kenez, and Peter. Cinema and Soviet society from the revolution to the death of Stalin /-[New ed. updated]. I.B. Tauris, 2001.

[4]. M. R. Zezina, L. R. Kershman, and B. S. Shulykin. Russian Cultural History. Shanghai Translation Publishing House, 2005.

[5]. Perloff, M. . "Common Places: Mythologies of Everyday Life in Russia." modern language quarterly 56.4(1995):519-523.

Cite this article

Zhao,X. (2025). Exploration of Nationalization and Stylistic Presentation in Soviet Animation of the 1950s-60s from an Iconographic Perspective. Communications in Humanities Research,57,146-155.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Literature, Language, and Culture Development

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Gu Qijun." The Evolution of Modern Animation Aesthetics in Soviet Russia." Film Arts 6(2018):9.

[2]. Pontieri, Laura. Russian Animation of the 1960s and the Khrushchev Thaw, Yale University, United States -- Connecticut, 2006. ProQuest,https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/russian-animation-1960s-khrushchev-thaw/docview/304980452/se-2.

[3]. Kenez, and Peter. Cinema and Soviet society from the revolution to the death of Stalin /-[New ed. updated]. I.B. Tauris, 2001.

[4]. M. R. Zezina, L. R. Kershman, and B. S. Shulykin. Russian Cultural History. Shanghai Translation Publishing House, 2005.

[5]. Perloff, M. . "Common Places: Mythologies of Everyday Life in Russia." modern language quarterly 56.4(1995):519-523.