1. Introduction

The adaptation of Shakespeare’s works into various cultural forms, particularly in cinema, has been an area of vibRant academic inquiry. While numerous studies have analyzed the general dynamics of such adaptations, significant gaps remain, particularly regarding the specific influences of Japanese artistic traditions like Noh and Kabuki on filmmakers like Akira Kurosawa. Additionally, there is a lack of in-depth exploration of how historical contexts—such as Japan’s feudal society and the tumultuous post-war period—impact the interpretation of Shakespearean narratives.

In King Lear localization can be carried further [1]. The complexity in the relationship between Shakespeare's King Lear and Akira Kurosawa's film Ran is augmented by the differences in medium, century, and the East - West divide [2]. Scholars increasingly examine how adaptations of Shakespeare's works, like King Lear, bridge cultural divides and reinterpret timeless themes. Kurosawa's Ran notably tRansports these elements into a Japanese context, enriching them with his cinematic language. Both works grapple with existential questions, particularly regarding the fragility of human relationships and the consequences of pride, highlighting cultural innovation while preserving Shakespeare's insights into the human condition.

This paper explores the interplay between King Lear and Ran, focusing on the film's visual language, narrative structure, and thematic resonances, particularly how these elements reflect Renaissance ideals. The study addresses several critical questions: This paper compares King Lear and Ran, focusing on character dynamics and plot. It looks at how Kurosawa adapts the play to Japanese culture. The role of visual storytelling in moral dilemmas is examined. Key areas include the influence of Noh and Kabuki, Japanese philosophy, and innovations in script, costume, and cinematography. Employing comparative analysis and insights from performance studies and film theory, this research aims to illuminate the broader implications of cross-cultural adaptations and their impact on global artistic expression.

2. Contextual framework

2.1. The story background

Shakespeare’s King Lear is a representative work of the Renaissance’s humanist sentiments, depicting the struggle between humanism and the darker, more greedy aspects of human nature, as well as the turbulent social conflicts that arise. Three hundred years later, on the other side of the world, a master from the East—Akira Kurosawa—became deeply interested in this play. The film tells a story that is as literal as its title, lit. ‘tumult or chaos’. The story, as depicted in the film, is set in 16th-century Japan during the Sengoku period, a time of civil war and territorial division among warring feudal lords. The Ichimonji Hidetora family, through slaughter and plunder, expands its power and secures a dominant position. Through this film, Kurosawa mirrors the real historical situation of Japan, which after decades of war was unified by Tokugawa Ieyasu, leading to the establishment of the Tokugawa shogunate. The political landscape during this period was both peaceful and despotic. Political instability and rampant ambition led Ieyasu to believe that foreign influence was the root cause of the wars and violence. As a result, he sealed Japan’s borders, ushering in a period of isolation that lasted for centuries. During this time, rebellions were rampant, and civil war continued for nearly a hundred years.

Sometimes, the process of adaptation becomes more preoccupied with culture rather than focusing on a close reinterpretation of the source text. Adaptations may sometimes comment on the politics of the source text or those of the background, or both, usually utilizing modification or addition [3]. The context of post-World War II Japan adds another layer of meaning to the film. Trousdale sees performance as moving beyond the stage and functioning throughout society, a characteristic of the culture as a whole [4]. The tragic themes of revenge and murder in Shakespeare’s work resonated deeply with a nation recently scarred by war. By 1950, Japan was in the midst of rebuilding, but the turmoil was widespread. As a defeated nation, the Japanese people sought not only economic recovery but also an outlet for their long - pent - up anger and frustration. Shakespeare's tragedy thus provided a profound cultural backdrop for Kurosawa's adaptation.

He took the film seriously as he said this, Ran would round out his life's work in film, he will put all of his remaining energy into it [5].

2.2. Similarities and differences between King Lear and Ran

As both the creator and victim of the chaos, the perpetrator of violence and the object of vengeance, Hidetora in Kurosawa’s film is not just a ‘man’—he is a ‘man of sin.’ In Ran (1985), therefore, he undertakes to give lchimonji Hidetora, Lear's counterpart, a history: "l try to make clear that his power must rest upon a lifetime of bloodthirsty savagery" [6]. This parallels King Lear. As king, Lear believes everything belongs to him and sees himself as the defender of order and morality, surrounded by flattery due to his former absolute power.

The positive characters in Shakespeare's plays and Akira Kurosawa's cinematic works often exhibit comparable moral characteristics. In King Lear, the youngest daughter, Cordelia, is depicted as straightforward and benevolent, demonstrating her devotion to her father by saving his life and upholding loyalty. In Ran, Tango Hirayama, a loyal retainer, arguably exemplifies the true spirit of the samurai. When Hidetora is not calm enough to ask for an abdication, Tango Hirayama boldly dares to admonish him with a blunt piece of advice.

Both King Lear and Hidetora share a similar anger towards their youngest child—Lear toward his daughter and Hidetora toward his son. Just as Lear is enraged by his daughters' failure to openly express their love, Hidetora is shocked by his son's perceived disloyalty. Both characters misinterpret familial affection, which causes them to lose their sanity and even their lives.

Kurosawa avoids idealizing the ending to please the audience. Saburo’s rescue of his father mirrors Cordelia’s act in King Lear, but both meet tragic deaths. Despite their willingness to save their fathers and leave governance to their siblings, the greed and thirst for vengeance of the others lead to a tragic conclusion.

Another subplot in King Lear involves Gloucester, who, deceived by his illegitimate son Edmund, exiles his legitimate son Edgar. Later, after sympathizing with Lear, Gloucester is blinded. While wandering as a beggar, he is unknowingly helped by Edgar. Kurosawa’s Tsurumaru shares qualities with both Gloucester and Edgar: like Gloucester, he is blinded, and like Edgar, he lives in isolation who, as a figure of self-redemption, spends his days comforted by the sound of his flute, without being a creator or avenger of hatred.

3. The making of Japan’s King Lear

3.1. Noh theatre and Kabuki

In terms of artistic expression, Ran draws heavily from traditional Japanese Noh theatre, enhancing the film's oriental cultural atmosphere. Noh, a medieval Japanese theatre form, combines dance, theatre, music, and poetry, with minimal dialogue. The performances in Ran are clearly influenced by Noh. Ran draws heavily from traditional Japanese Noh theatre, enhancing its oriental cultural flavor.

The performances in Ran are clearly influenced by Noh theatre, especially in the character of Kyoami. Through chant-like dialogue and exaggerated physical movements, Kyoami highlights Hidetora's plight, driven by the conflict with his two sons, leading to his eventual exile and ruin.

The acting style of characters such as Hidetora and Lady Kaede in Ran is influenced by Japanese Noh Theatre, which highlights the passionate, callous, and single-minded qualities of these characters. Long intervals of static motion and silence followed by impetuous and wild change in manner and the heavy ghostlike make-up of Hidetora resembles the masks of Noh performers [3].

Tsurumaru, a multifaceted character created by Kurosawa, expresses his inner pain through art. As a figure of self-redemption. He lives in a hovel on the heath, playing the flute—an instrument associated with madness or the supernatural in Kabuki.

3.2. Japanese philosophy: Shinto and Buddhism

Akira Kurosawa created Japan's version of King Lear through his film Ran.

At the beginning of the film, Hidetora, along with his three sons and his ministers. Everyone gathered together, setting out to hunt wild boars. The point of this activity is not necessarily to catch, but to pursue the boar. In Japanese philosophy, physical exertion causes the material world to fade, guiding the body toward Buddha Amita. This idea, deeply valued in Japanese thought, plays a central role throughout the film. Shinto and Buddhism - these religious and philosophical beliefs have a profound influence on artistic creation, with an emphasis on themes such as nature, destiny, and human behavior [7].

The film repeatedly conveys a critical philosophy, such as Kyoami’s line: "In a chaotic world, it’s normal to be insane." This line, spoken by an insignificant character, cleverly critiques the disorder of the time. Kyoami, loyal yet ridiculed, embodies the absurdity of the situation. His candid remarks reveal the truth, but who listens? In a world of chaos, how can anyone hear the wisdom of the powerless? Thus, everything is in disorder, which is why the film is titled Ran.

In both King Lear and Ran, natural imagery plays a significant role, expanding the scope and depth of the narrative. In the famous heath scene (Act 3, Scenes 2-4) of King Lear, Lear after being cast out by his daughters, finds himself at the mercy of the storm. He equates the storm with his inner turmoil, stating, "Within this small body of mine, a struggle more intense than the storm is raging. On such a night... I entrust everything to the unknown forces [8]." Here, the weather not only drives the plot but also reflects the characters' psychological and emotional shifts.

In Kurosawa’s film, Hidetora’s suffering amid the harsh elements and the disorienting maze reflects the chaos he himself has sown. Kurosawa suggests that Hidetora is not only shaped by his environment but, in a deeper sense, is responsible for it. This concept mirrors Shakespeare’s portrayal of Lear on the heath, where the storm externalizes his inner turmoil, while also expanding on the Japanese philosophical view of the interconnectedness between humans and their surroundings.

4. Film re-adaptation of audiovisual language

4.1. Script adaptation and innovation

Ran should be considered as an adaptation of King Lear, not a tRanslation. since, unlike other adaptations of King Lear, the film seeks neither to remain faithful Shakespeare's language nor to provide “visual equivalents” in another medium [9]. Classic drama adaptations often face the challenge of maintaining the stage-bound narrative style, especially in works like Shakespeare's, which feature intricate structures and complex dialogue. Overly adhering to the original text can result in a film with rigid plotlines and uneven pacing, while too much alteration may diminish the original's charm. Ran's successful adaptation is a breakthrough and innovation by Akira Kurosawa in tackling this dilemma.

In adapting Ran, Kurosawa cleverly tRansplanted the historical setting of Shakespeare's King Lear to Japan's Warring States period, completely breaking free from the constraints of traditional stage drama. The film visually captures the story background of King Lear while dismantling the formalized structure of the play, allowing the narrative to flow more dynamically.

Thematic-wise, Ran has the advantage over King Lear of being conciseness full-bodied and multifaceted. In addition to the theme of revenge, it addresses power, hatred, ambition, cruelty, betrayal, samurai spirit, masculism and women's issues, forming a gRand epic of war. The adaptation of Ran is the result of Kurosawa's ingenious craftsmanship, artistic brilliance, and a fresh approach to the source material.

4.2. Costumes

In terms of the film's visual expression, Ran also showcases Akira Kurosawa's deep understanding and respect for ancient Japanese culture. Through careful costume and prop design, he vividly presents the social and cultural atmosphere of 16th-century Japan.

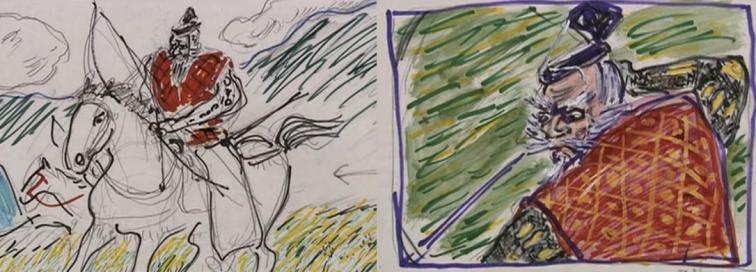

For several years, when Kurosawa was unable to secure funding, he had to create hand-drawn drafts of the film's footage one after another (As shown in Figure 1). In his statement, Akira Kurosawa said, "As you work on the drawings, your ideas gradually become clearer. Everyone's mental state, even their lighting and costumes, is drawn out" [10].

Figure 1: Akira Kurosawa's film manuscripts [10]

The vibRant colors contrast sharply with the weight of the tragedy, and the screen is filled with a variety of colorful hues for much of the film. At the beginning, the three sons gather with their father, Hidetora. The eldest son, Taro, wears red, while the second son, Jiro, wears yellow. However, after Taro’s death, Jiro adopts red as his signature color, while Saburo is dressed in blue. Hidetora begins in golden attire, later turning to white, and his skin becomes a ghastly pale white. The use of these colors not only highlights the personalities of the characters but also enhances the visual impact of the film. Bonnie Melchior argues that Kurosawa had a deeper understanding of color usage and color theory than his contemporaries in the film industry: Like the use of camera angles, use of color becomes a means to distance spectators, to make them view Hidetora’s choices and the consequences of those choices from a social and cosmic rather than personal perspective [11]. The impact of the colors is overwhelming, almost like a painting.

4.3. Cinematography and audiovisual language

Akira Kurosawa's cinematography is an aesthetic delight, with each frame resembling a work of art, blending a strong sense of storytelling with artistic expression. The smooth tRansitions between shots effectively convey a Range of emotions and plot developments, leaving a powerful impact on the viewer.

His use of natural landscapes is equally impressive. Through the depiction of mountains, rivers, mist, and seasonal changes, he successfully creates the ambiance of Japan's Warring States period. At the same time This film notable for its large-scale battle scenes and gRand production design. Technically, for example, Kurosawa opposes close-ups and favours long shots. Par from letting you look into a character's soul, he argues, close-ups merely encourage an actor to be lazy and not to act with his whole body [12].

Through the use of shot tRansitions and movement, the film immerses the audience in a completely unfamiliar world. This narrative style not only makes the film's pacing more intense but also allows the audience to deeply feel the characters' inner worlds and emotional changes.

5. Conclusion

This study has analyzed the tRansformation of characters and themes from King Lear to Ran, highlighting the adaptation of Shakespeare’s universal themes of power, family, and betrayal through the lens of Japanese culture. The analysis focused on the differences and similarities between the two works, particularly in how Kurosawa reinterprets these themes using traditional Japanese aesthetics, including influences from Noh and Kabuki theatre, and the philosophical frameworks of Shinto and Buddhism. Kurosawa’s innovative approach in adapting the script, his choices in costumes, and his visual storytelling techniques were also explored, revealing how these elements contribute to the thematic depth of the film while maintaining the essence of the original play.

The findings show that Kurosawa successfully adapted King Lear into a narrative that resonates with both Japanese cultural values and global humanistic themes. His film underscores the destructive consequences of personal desires, internal conflicts, and betrayal, presenting characters whose moral struggles mirror those of the Shakespearean play. Furthermore, Kurosawa’s reworking of the narrative emphasizes the universality of Shakespeare’s exploration of human nature, while also offering a unique commentary on Japanese historical and cultural contexts.

However, this study has some limitations. While the research draws from a wide Range of secondary sources, including scholarly articles, books, and interviews with film critics, it did not incorporate primary empirical research methods, such as direct surveys or audience studies, which could provide more insights into how viewers interpret and respond to the film in different cultural contexts. Additionally, although the study covered the adaptation of key themes and visual elements, a more detailed analysis of the cinematographic techniques and their emotional impact could further enrich the understanding of Kurosawa’s visual storytelling.

Future research could explore a broader Range of perspectives, such as more extensive interviews with filmmakers or critics, and empirical studies that assess the audience's reactions to Ran compared to King Lear. Further studies could also delve into a deeper comparative analysis of other adaptations of King Lear across different cultures and cinematic traditions, offering a more comprehensive understanding of how Shakespeare's work tRanscends cultural boundaries.

As Kurosawa himself states, he is "committed to finding a balance between Western and Eastern art."

In conclusion, Kurosawa's "Ran" is a remarkable adaptation of "King Lear". It retains Shakespeare's exploration of human - related themes and integrates them into Japan's rich cultural and philosophical context. This study highlights how Kurosawa’s artistic innovations offer a fresh perspective on the play, bridging cultural and temporal divides.

References

[1]. Orgel, S., Keilen, S. (1999) Shakespeare and History. [online] Google Books, p. 75. Available at: https://books.google.com.hk/books?hl=zh-CN&lr=&id=klxj_ecxIqcC&oi=fnd&pg=PP7&dq=Orgel

[2]. Hoile, C. (1987) "King Lear and Kurosawa's Ran: Splitting, Doubling, Distancing." Pacific Coast Philology, 29–34. https://doi.org/10.2307/1316655

[3]. BalachandRan, A. (2019) "From Text to Screen: The Metamorphosis of King Lear to Ran," p. 436. https://stmcc.in/public/NAAC/PB%20j%202019%20Arya%20JETIR1907204(1).pdf

[4]. Orgel, S., Keilen, S. (1999) Shakespeare in the Theatre. Garland, New York, pp.Introduction. https://books.google.com/books?hl=zh-CN&lr=&id=g4Fp7FiRGOcC&oi=fnd&pg=PP9&dq=Orgel,+Stephen+Shakespeare%27s&ots=lFOTfzcvtA&sig=BzRDELJyJ8-jd9kn_VaPbDYSoW8#v=onepage&q=Orgel%2C%20Stephen%20Shakespeare's&f=false

[5]. Kurosawa, A. (1983) Something Like an Autobiography. Vintage Books, New York.

[6]. Grilli, P. (1985) "Kurosawa Directs a Cinematic Lear: Interview with Peter Grilli." New York Times, Dec. 15, 1985, Section 2: 1.

[7]. Donahue, A. (2009) "From Text to Film: Culture, Color, and Context in Akira Kurosawa’s Ran," pp. 83–85. https://jsimonconsulting.com/fc/pdf/2009_SP_83-93.pdf

[8]. Shakespeare, W. (1608) King Lear, Act 3, Scenes 2-4. https://www.shakespeare.org.uk/

[9]. Parker, B. (1986) "Ran and the Tragedy of History." University of Toronto Quarterly, 55: 412–423. [CSA] https://muse.jhu.edu/pub/50/article/514930/pdf

[10]. Toho Masterworks. (2025) Akira Kurosawa: It Is Wonderful to Create - A 30-minute documentary on the making of Ran. Bilibili. https://www.bilibili.com/video/BV1kr4y1878P/?spm_id_from=333.337.search-card.all.click

[11]. Melchior, B. (2005) "King Lear and Ran: Identity TRanslated and TRansformed." East-West Connections: Review of Asian Studies, 5.1: 41–53.

[12]. Lai, M. L. (1993) Akira Kurosawa's use of Noh in The Throne of Blood, his film adaptation of William Shakespeare's Macbeth. California State University, Long Beach.

Cite this article

Yang,C. (2025). A Localized King Lear: Adaptation, Innovation and Tradition in Kurosawa’s Ran. Communications in Humanities Research,57,198-203.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Literature, Language, and Culture Development

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Orgel, S., Keilen, S. (1999) Shakespeare and History. [online] Google Books, p. 75. Available at: https://books.google.com.hk/books?hl=zh-CN&lr=&id=klxj_ecxIqcC&oi=fnd&pg=PP7&dq=Orgel

[2]. Hoile, C. (1987) "King Lear and Kurosawa's Ran: Splitting, Doubling, Distancing." Pacific Coast Philology, 29–34. https://doi.org/10.2307/1316655

[3]. BalachandRan, A. (2019) "From Text to Screen: The Metamorphosis of King Lear to Ran," p. 436. https://stmcc.in/public/NAAC/PB%20j%202019%20Arya%20JETIR1907204(1).pdf

[4]. Orgel, S., Keilen, S. (1999) Shakespeare in the Theatre. Garland, New York, pp.Introduction. https://books.google.com/books?hl=zh-CN&lr=&id=g4Fp7FiRGOcC&oi=fnd&pg=PP9&dq=Orgel,+Stephen+Shakespeare%27s&ots=lFOTfzcvtA&sig=BzRDELJyJ8-jd9kn_VaPbDYSoW8#v=onepage&q=Orgel%2C%20Stephen%20Shakespeare's&f=false

[5]. Kurosawa, A. (1983) Something Like an Autobiography. Vintage Books, New York.

[6]. Grilli, P. (1985) "Kurosawa Directs a Cinematic Lear: Interview with Peter Grilli." New York Times, Dec. 15, 1985, Section 2: 1.

[7]. Donahue, A. (2009) "From Text to Film: Culture, Color, and Context in Akira Kurosawa’s Ran," pp. 83–85. https://jsimonconsulting.com/fc/pdf/2009_SP_83-93.pdf

[8]. Shakespeare, W. (1608) King Lear, Act 3, Scenes 2-4. https://www.shakespeare.org.uk/

[9]. Parker, B. (1986) "Ran and the Tragedy of History." University of Toronto Quarterly, 55: 412–423. [CSA] https://muse.jhu.edu/pub/50/article/514930/pdf

[10]. Toho Masterworks. (2025) Akira Kurosawa: It Is Wonderful to Create - A 30-minute documentary on the making of Ran. Bilibili. https://www.bilibili.com/video/BV1kr4y1878P/?spm_id_from=333.337.search-card.all.click

[11]. Melchior, B. (2005) "King Lear and Ran: Identity TRanslated and TRansformed." East-West Connections: Review of Asian Studies, 5.1: 41–53.

[12]. Lai, M. L. (1993) Akira Kurosawa's use of Noh in The Throne of Blood, his film adaptation of William Shakespeare's Macbeth. California State University, Long Beach.