1. Introduction

National image refers to a country’s perception and reputation on the international stage. Boulding defines national image as how a nation perceives its identity and its relationships with other entities within the global arena[1]. It represents a country’s outward manifestation and reflects the external expression of its core identity and values[2]. National image and soft power are deeply interconnected, with the formation of national image playing a crucial role in the projection of a country’s soft power. According to Nye, soft power relies on attraction, fostering shared aspirations through appeal rather than coercion. It is a non-coercive form of influence that relies on a country’s culture, political values, and foreign policies to extend its impact on others[3].

The enhancement of national soft power is facilitated by cultural diplomacy and international cultural exchanges and guides national public diplomacy. Kazuo posits that cultural diplomacy employs cultural instruments to augment a nation’s geopolitical leverage and constitutes an integral aspect of foreign policy. Conversely, international cultural exchange prioritizes reciprocal inspiration over political objectives. Public diplomacy aims to influence global public opinion about a country or its policies, and the two overlap in their efforts to enhance national image through cultural activities [4]. In this paper, soft power refers to a country’s ability to enhance its national image through attraction, with cultural diplomacy, public diplomacy, and international cultural exchanges as important means to achieve this goal. Culture plays a vital role as a resource in this process.

The Japanese government has consistently promoted the development of the cultural industry, engaged in public diplomacy activities, and utilized international sporting events as platforms for cultural dissemination. Through the execution of the “Cool Japan” initiative, Japan has assimilated components such as anime, culinary arts, and fashion into its national branding, enhancing the nation’s global allure and underscoring the distinctiveness of Japanese culture [5]. Guided by the “Cool Japan” Strategy, Japan leveraged the export of popular culture (including animation, music, film, and television) to stimulate its economy, enhance its national image, and strengthen its soft power after World War II, which gained widespread acceptance both in Asia and globally. For instance, during the 1970s, Japan began to surpass the United States as the dominant source of pop culture in Asia. By the 1980s and 1990s, its pop culture had become particularly popular among the younger generation across the region [6].

This paper investigates how the “Cool Japan” cultural policy reshaped Japan’s international image after World War II. Moreover, how the “Cool Japan” cultural policy has contributed to the development of Japan’s soft power. This study enriches Joseph Nye’s soft power framework by empirically validating its application in a non-Western context. By analyzing Japan’s “Cool Japan” strategy, the paper demonstrates how cultural assets can serve as non-coercive tools for shaping national image and fostering international influence. It expands the discourse on soft power beyond traditional political and institutional frameworks, emphasizing cultural industries as critical drivers of global attraction.

2. “Cool Japan” strategy

“Cool Japan” is an initiative by the Japanese government to shape the national brand and enhance soft power. It integrates and promotes Japan’s unique culture, products, and lifestyle, emphasizing its attractiveness to strengthen international influence and stimulate economic growth. The strategy incorporates elements from various fields, including anime, music, cuisine, fashion, and technology, to create a Japanese image that holds global appeal [7].

Following the 1990s collapse of Japan’s bubble economy, traditional industries experienced stagnation, while youth-centric sectors like anime and video games rapidly emerged as vital export industries. The “Cool Japan” image has supplanted the traditional “Corporate Japan” narrative. Concurrently, Japan faces international challenges, including waning industrial competitiveness and adverse public sentiment due to historical grievances. In response, the Japanese government initiated an intellectual property strategy focused on innovation and creative products in 2002, leading to the development of the “Cool Japan” strategy [8].

In 2014, the Cool Japan Movement Promotion Council issued the COOL JAPAN PROPOSAL, which redefined the “Cool Japan” Strategy as a broad concept of expressing Japan’s attractiveness to other countries [9]. Based on areas such as food, anime, and pop culture, it has the potential for infinite growth, extending across various sectors in response to evolving global interests. “Cool Japan” aims to position Japan as a nation that provides creative solutions to global challenges.. After experiencing a period of rapid economic growth, Japan faces numerous social issues, such as an aging population, disappearing communities, and environmental and energy concerns, which other countries may also encounter in the future. Japan wants to combine its experiences in addressing domestic issues with its creative industries to offer valuable innovations to the world, thereby demonstrating its global significance.

To achieve this mission, Japan has outlined a three-step approach. The first step focuses on fostering domestic development by enhancing communication capabilities with foreign countries. This includes offering engaging courses, improving study abroad programs, promoting English-language broadcasting, and establishing English-speaking districts to help citizens develop international communication skills. The second step is to strengthening Japan’s international presence by cultivating a more positive global image. This involves creating a new brand identity, updating slogans, showcasing “Japanese design,” and improving government procurement practices. Japan aims to enhance the flow of information and cultural products through inbound websites, translating tourism logos, and supporting content translation. The third step focuses on positioning Japan as a nation that contributes to global well-being by addressing domestic and global challenges. This involves visualizing these issues through information design, disclosing government data, and integrating these insights into the design process. Ultimately, Japan aims to advance its traditional philosophy through the establishment of JAPAN LABO, the organization of international craft festivals, the construction of a Japanese design museum, and the promotion of aesthetic development among Japanese youth [9].

3. The evolution of Japan’s international image following the implementation of the “Cool Japan” strategy

After World War II, Japan implemented post-war reforms under the guidance of the United States, revised its constitution, embarked on a democratization process, and sought to transform its post-war image from militarism to a peace-loving democratic nation.

The “Cool Japan” Strategy has significantly enhanced Japan’s global image. A 2015 survey of respondents from France, Germany, Poland, Spain, and the UK revealed that 93% recognized Japan’s rich traditions and culture, 90% acknowledged its robust economy and advanced technology, and 75% noted its commitment to peace since World War II. Additionally, 75% appreciated Japan’s natural beauty, 69% acknowledged its cultural dissemination, and 66% cited its high living standards. Interest in Japanese culture, including traditional, popular, and culinary aspects, was expressed by 73%, while 70% showed interest in its history. Notably, responses varied by age, gender, and education, with 74% of those aged 18-29 interested in culture and 68% in history, compared to 69% and 67% of respondents aged 60 and above, respectively [10].

Driven by the “Cool Japan” policy, Japan’s international image has expanded from a single “animation power” to a crucial link in the chain of global relations. For example, at the World Economic Forum’s Annual Meeting in 2024, experts affirmed Japan’s important role as a bridge between Asia and the rest of the world. Taro Kono, Japan’s Minister of Digital Transformation, asserts that Japan is uniquely positioned to serve as a mediator between diverse groups, highlighting the country’s ability to act as a genuine intermediary in connecting various stakeholders [11].

4. The impact of the “Cool Japan” strategy on Japan’s soft power

4.1. The promotion of Japanese cultural communication

Under the Cool Japan strategy, Japan has exported its cultural industries globally, with anime being the foremost and most renowned among them. Although the term “anime” is commonly used in Japanese to refer to all animated works, it is employed in other countries to specifically describe animation produced in Japan or to denote a distinct aesthetic associated with Japanese animation and related media. In 2023, the anime sector achieved an unprecedented total revenue of 33.5 trillion yen, with international earnings from Japan’s animation industry experiencing consistent growth, reaching around 17.2 trillion yen for the first time in 2023 [12]. This segment is projected to expand at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 3.9% from 2024 to 2030 [13].

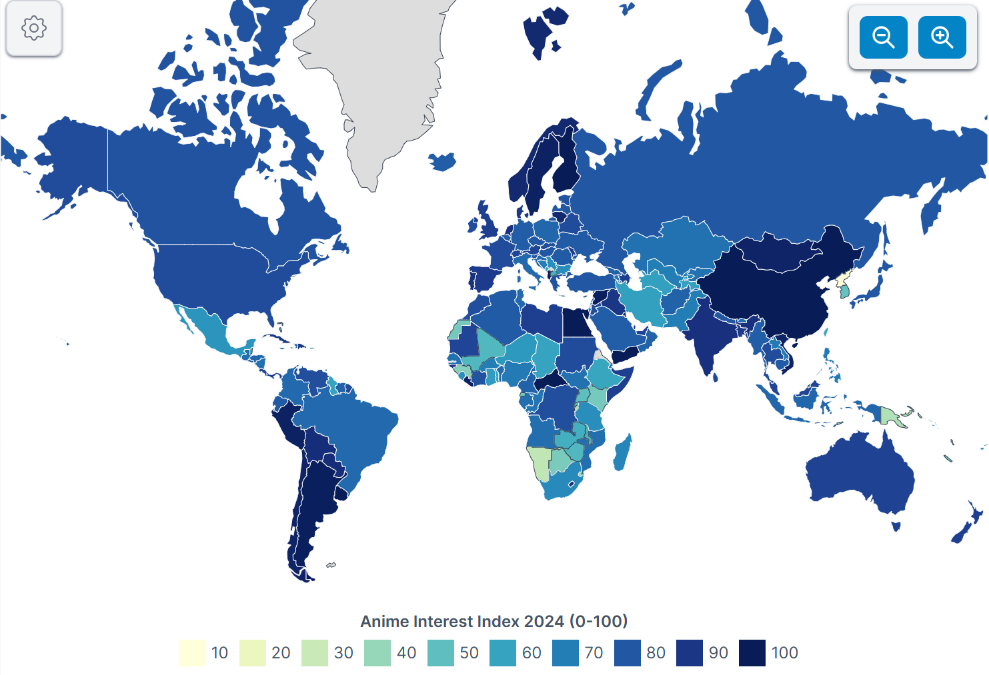

Japanese anime has a large and dedicated global fanbase, enjoying widespread popularity across diverse regions. According to recent statistics, 2024, twelve countries exhibited the highest popularity for Japanese anime in 2024, each with a popularity score of 100. Additionally, 146 countries recorded a popularity rating of 70 or higher for Japanese anime. The ten countries with the greatest increase in favorability toward Japanese anime compared to 2023 are Kiribati, China, Anguilla, Luxembourg, DR Congo, Macau, French Guiana, Taiwan, Sudan, and the Republic of the Congo[14].

Figure 1: Anime interest index 2024 (0-100) [14]

Table 1: Anime interest index [14]

Country | AnimePopularityInterest2024 | AnimePopularityInterest2023 |

Kiribati | 100 | / |

China | 100 | 12 |

Anguilla | 100 | 16 |

Luxembourg | 100 | 38 |

DR Congo | 82 | 26 |

Macau | 63 | 16 |

French Guiana | 83 | 36 |

Taiwan | 59 | 13 |

Sudan | 83 | 38 |

Republic of the Congo | 72 | 28 |

The growth of the Japanese anime industry has also spurred the development of related sectors, such as the media industry, karaoke, and tourism. Anime is no longer confined to printed works; it is now animated and streamed on platforms such as Netflix. Additionally, the emphasis on producing theme songs has further fueled the growth of karaoke and enhanced market vitality. As a result of anime’s global promotion, Japan has seen a significant influx of foreign tourists, with statistics indicating that the number of international visitors will reach 36,869,900 in 2024 [15]. Social media is a key tool of soft power, offering countries a platform to directly share cultural content with a global audience. Japan has effectively leveraged social media to accelerate the global expansion of the anime industry, broaden its viewership, and innovate the methods of anime communication. Anime fans actively cosplay their favorite characters and discuss related topics on social media, fostering a dynamic exchange and communication among anime enthusiasts from different countries.

4.2. International recognition

The “Cool Japan” Strategy seeks to position Japan as a nation capable of offering innovative solutions to global challenges. Japan has strived to take leadership across a wide range of areas, including international trade, politics, and regional cooperation. Following the United States withdrawal from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) in January 2017, Japan assumed a leading role in the expansion negotiations, navigating the crisis and securing the implementation of the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) with the remaining 11 countries in 2018. Furthermore, Japan has implemented the concept of Data Free Flow with Trust (DFFT), advocating for the establishment of rules governing cross-border data flow and spearheading international efforts to bring this vision to fruition.

The 2021 Tokyo Olympics represents a significant opportunity for the advancement of Japan’s soft power. Sports diplomacy serves as a facet of Japan’s public diplomacy strategy. Despite initial pessimistic forecasts related to the pandemic, the Tokyo 2021 Games, which were postponed, ultimately proceeded without major disruptions, and the transmission of the virus was effectively managed [16]. However, there is still public controversy over Japan’s opening and closing ceremonies, which shows the problems and exoticization of Japan’s cultural displays and the furtherance of its “Cool Japan” strategy. It positions the country beyond Asia and outside of Europe, an awkward position that can lead to a dilution of national identity to a certain extent.

5. Conclusion

The “Cool Japan” strategy has played a transformative role in reshaping Japan’s post-war international image and enhancing its soft power on the global stage. By strategically leveraging cultural exports such as anime, cuisine, fashion, and technology, Japan has successfully transitioned from a nation historically associated with wartime militarism to one recognized for its innovation, modernity, and cultural vibrancy. The strategy’s success lies in its ability to align cultural diplomacy with economic goals, cultivating a dynamic national brand that appeals to diverse audiences.

The “Cool Japan” Strategy has significantly bolstered Japan’s global image. A 2015 survey across France, Germany, Poland, Spain, and the UK indicated that 93% recognized Japan’s cultural heritage, 90% acknowledged its strong economy and advanced technology, and 75% noted its post-World War II commitment to peace. Furthermore, 75% appreciated Japan’s natural beauty, 69% recognized its cultural influence, and 66% cited its high living standards. Interest in Japanese culture, encompassing traditional, popular, and culinary elements, was expressed by 73%, while 70% showed interest in its history. Notably, responses varied by demographics, with 74% of respondents aged 18-29 interested in culture and 68% in history, compared to 69% and 67% among those aged 60 and above, respectively.

References

[1]. Boulding, K. E. (1959). National Images and International Systems. The Journal of Conflict Resolution, 3(2), 120–131. https://www.jstor.org/stable/173107

[2]. Hai-ming, Z., Qian, X., Rong-chun, J., & Sen, Z. (2021). On the Discursive Construction of National Image from the Perspective of Appraisal Theory. English Language, Literature & Culture, 6(2), 37. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.ellc.20210602.13

[3]. Nye, J. S. (1990). Bound To Lead: The Changing Nature Of American Power. Basic Books. ISBN 9780465001774. Retrieved 1 March 2020.

[4]. Ang, I., Isar, Y. R., & Mar, P. (2018). Cultural diplomacy: beyond the national interest. In Cultural Diplomacy: Beyond the National Interest? (pp. 11-27). Routledge.

[5]. Izuyama, M. (Ed.). (2022). EAST ASIAN STRATEGIC REVIEW [Review of EAST ASIAN STRATEGIC REVIEW].

[6]. Lux, G. (2021). Cool Japan and the Hallyu Wave: The Effect of popular culture exports on national image and soft power.

[7]. Tamaki, T. (2019). Repackaging national identity: Cool Japan and the resilience of Japanese identity narratives. Asian Journal of Political Science, 27(1), 108-126.

[8]. Daliot-Bul, M. (2009). Japan Brand Strategy: The Taming of “Cool Japan” and the Challenges of Cultural Planning in a Postmodern Age. Social Science Japan Journal, 12(2), 247–266. https://doi.org/10.1093/ssjj/jyp037

[9]. Cool Japan Movement Promotion Council. (2014). COOL JAPAN PROPOSAL.

[10]. Kunert, M., Hofrichter, J., & Anja Miriam Simon, A. (n.d.). Image of Japan in five European countries A representative survey on behalf of the Embassy of Japan in Germany.

[11]. Naoko Tochibayashi, & Kutty, N. (2024, January 22). Japan’s pivotal global role: Insights from Davos 2024. World Economic Forum. https://www.weforum.org/stories/2024/01/japan-insights-davos-2024/

[12]. Anime industry in Japan. (2024, February 19). Statista. https://www.statista.com/topics/7495/anime-industry-in-japan/#topicOverview

[13]. Japan Anime Market Size, Share & Growth | Report, 2030. (n.d.). Www.grandviewresearch.com. https://www.grandviewresearch.com/industry-analysis/japan-anime-market-report

[14]. World Population Review. (2024). Anime Popularity by Country 2024. World Population Review. https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/anime-popularity-by-country

[15]. Japan National Tourism Organization. (2025). Number of foreign visitors to Japan (December 2024 and annual estimates).

[16]. Carminati, D. (2022). The State of Japan’s Soft Power After the 2020 Olympics.

Cite this article

Yang,D. (2025). An Analysis of the Evolution and Influence of Japan’s “Cool Japan” Strategy on National Image and Soft Power. Communications in Humanities Research,60,66-71.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Literature, Language, and Culture Development

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Boulding, K. E. (1959). National Images and International Systems. The Journal of Conflict Resolution, 3(2), 120–131. https://www.jstor.org/stable/173107

[2]. Hai-ming, Z., Qian, X., Rong-chun, J., & Sen, Z. (2021). On the Discursive Construction of National Image from the Perspective of Appraisal Theory. English Language, Literature & Culture, 6(2), 37. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.ellc.20210602.13

[3]. Nye, J. S. (1990). Bound To Lead: The Changing Nature Of American Power. Basic Books. ISBN 9780465001774. Retrieved 1 March 2020.

[4]. Ang, I., Isar, Y. R., & Mar, P. (2018). Cultural diplomacy: beyond the national interest. In Cultural Diplomacy: Beyond the National Interest? (pp. 11-27). Routledge.

[5]. Izuyama, M. (Ed.). (2022). EAST ASIAN STRATEGIC REVIEW [Review of EAST ASIAN STRATEGIC REVIEW].

[6]. Lux, G. (2021). Cool Japan and the Hallyu Wave: The Effect of popular culture exports on national image and soft power.

[7]. Tamaki, T. (2019). Repackaging national identity: Cool Japan and the resilience of Japanese identity narratives. Asian Journal of Political Science, 27(1), 108-126.

[8]. Daliot-Bul, M. (2009). Japan Brand Strategy: The Taming of “Cool Japan” and the Challenges of Cultural Planning in a Postmodern Age. Social Science Japan Journal, 12(2), 247–266. https://doi.org/10.1093/ssjj/jyp037

[9]. Cool Japan Movement Promotion Council. (2014). COOL JAPAN PROPOSAL.

[10]. Kunert, M., Hofrichter, J., & Anja Miriam Simon, A. (n.d.). Image of Japan in five European countries A representative survey on behalf of the Embassy of Japan in Germany.

[11]. Naoko Tochibayashi, & Kutty, N. (2024, January 22). Japan’s pivotal global role: Insights from Davos 2024. World Economic Forum. https://www.weforum.org/stories/2024/01/japan-insights-davos-2024/

[12]. Anime industry in Japan. (2024, February 19). Statista. https://www.statista.com/topics/7495/anime-industry-in-japan/#topicOverview

[13]. Japan Anime Market Size, Share & Growth | Report, 2030. (n.d.). Www.grandviewresearch.com. https://www.grandviewresearch.com/industry-analysis/japan-anime-market-report

[14]. World Population Review. (2024). Anime Popularity by Country 2024. World Population Review. https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/anime-popularity-by-country

[15]. Japan National Tourism Organization. (2025). Number of foreign visitors to Japan (December 2024 and annual estimates).

[16]. Carminati, D. (2022). The State of Japan’s Soft Power After the 2020 Olympics.