1. Introduction

Interest rates, as one of the fundamental variables in financial markets, have undergone continuous adjustments and fluctuations in recent years. These changes have had profound implications for supply and demand dynamics as well as price levels within the real estate market. Given that the real estate sector constitutes a crucial component of national economies across many countries, fluctuations in property prices exert significant influence on economic stability and growth.

The impact of interest rate changes on real estate prices operates through multiple mechanisms. One of the primary channels is the cost of property acquisition for buyers. When interest rates rise, borrowing costs increase, discouraging potential homebuyers and leading to a decline in housing demand, which subsequently results in falling property prices. Conversely, a decrease in interest rates lowers borrowing costs, stimulating housing demand and driving property prices upward. Empirical research shows a negative correlation between short-term real interest rates and property prices data from 35 large and medium-sized cities in China between 2000 and 2012 [1]. Thus, an increase in interest rates tends to suppress property price growth.

However, the relationship between interest rates and real estate prices is not universally straightforward. For instance, while lower interest rates reduce homeownership costs, their effect on property prices remains limited in the absence of sufficient market demand. In Japan, pro-longed periods of low interest rates have not necessarily translated into significant property price increases [2]. In other words, declining interest rates do not always guarantee rising property values if underlying economic conditions do not support sustained housing demand. Additionally, changes in interest rates influence investment behavior in the real estate sector. In a low-interest-rate environment, real estate assets become relatively more attractive compared to other investment options, leading to increased capital inflows into the property market and driving up prices. Conversely, in a high-interest-rate environment, capital may shift toward alternative financial assets offering higher yields, thereby exerting downward pressure on property prices. A notable example of this dynamic is observed in China’s response to the 2008 Global Financial Crisis. The People’s Bank of China (PBOC) implemented a series of interest rate cuts to stimulate the real estate market, resulting in a rapid rebound in housing prices, highlighting the stimulatory effect of low interest rates on property values [3].

This study aims to examine the mechanisms through which interest rate fluctuations impact property prices, with a particular focus on the differing responses of the real estate markets in China and Japan. By analyzing the development trajectories of the property sectors in both countries and conducting comparative analyses, this research seeks to uncover the extent to which interest rate policies shape housing market dynamics in distinct economic and institutional contexts.

2. Overview of China and Japan’s real estate market

Over the past two decades, China’s rapid economic growth has exhibited a strong positive correlation with the prosperity of its real estate market, which has become a major driver of economic development. However, excessive reliance on real estate has also introduced the potential significant risks for real estate market bubbles which increased particularly when property prices rise too quickly. In response, the Chinese government has implemented a series of regulatory measures in recent years, including Housing Purchase Restriction Policy, Loan Restriction Policy, and Interest Rate Cut Policy, in order to curb speculation and prevent excessive price inflation. These measures are all aimed at influencing property prices.

Similarly, Japan’s real estate market has undergone notable fluctuations. Between 1956 and 1990, substantial housing demand was fueled by strong economic growth and a rapidly expanding population, but it also contributed to the formation of a real estate bubble. The combination of loose monetary policy, financial liberalization, and speculative investment behavior further exacerbated market overheating [4]. In an attempt to curb excessive real estate speculation, the Japanese government adopted contractionary monetary policies and raised the benchmark interest rate between 1991 and 2008. However, the overly stringent regulatory measures led to a sharp collapse of the real estate bubble, triggering a prolonged period of economic stagnation known as the “Lost Two Decades” [5]. Since 2009, Japan’s economy has shown signs of recovery, under the Abenomics, a set of economic policies aimed at revitalizing growth. Household incomes have gradually increased, and the real estate market has experienced a moderate rebound. Additionally, a persistently low-interest-rate environment has effectively reduced the cost of homeownership, leading to a gradual release of pent-up housing demand.

3. China’s real estate market

Interest rate fluctuations have a significant impact on both homebuyers and property sellers. For homebuyers, interest rate adjustments directly affect mortgage loan rates. When the central bank lowers the Loan Prime Rate (LPR), mortgage rates decrease correspondingly, reducing monthly repayment obligations and overall homeownership costs. This reduction enhances affordability and strengthens buyers’ willingness to enter the market. In 2024, the PBOC cut policy rates twice, totaling 0.3 percentage points, which led to cumulative reductions of 0.35 percentage points for the one-year LPR and 0.6 percentage points for the five-year or longer LPR [6]. These adjustments improved homebuyers’ purchasing power and contributed to increased housing demand.

For property sellers, lower interest rates can stimulate the demand, which led to an intensifying market competition and potentially driving up housing prices. In such conditions, sellers may achieve higher transaction prices and expanding their profit margins, as a result creating a more active property market. However, the supply-demand balance was influenced by the environment of China’s real estate market, which are continuously evolving due to ongoing urbanization and demographic shifts. In cases of housing oversupply, even with lower interest rates, the potential for significant price increases may be constrained.

3.1. The impact of decreasing interest rates

Interest rate fluctuations influence real estate prices not only by affecting homebuyers and developers, but also by shaping real estate market dynamics across different geographic regions, particularly between first-tier and second-tier cities. One of the key factors shaping this difference is the Price-to-Rent Ratio, which varies across cities and affects housing demand dynamics.

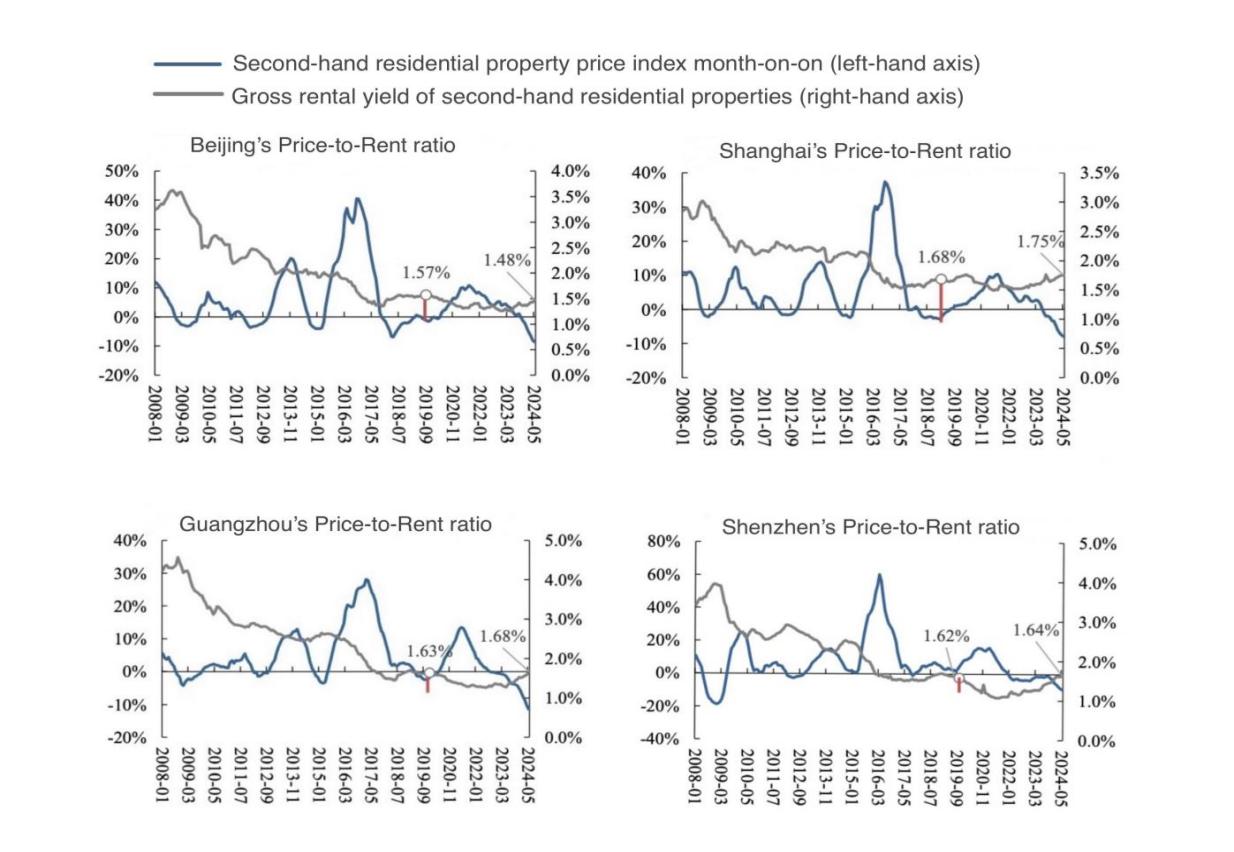

Figure 1: Price-to-Rent Ratio from 2008 to 2024 in Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou and Shenzhen (data from: wind, China National Bureau of Statistics (NBS), Soochow Securities)

Interest rate adjustments, along with the introduction of China’s Housing Purchase Restriction Policy, have influenced the supply-demand balance in the real estate market. In China, the Price-to-Rent Ratio differs significantly among cities, affecting buyers’ decisions. When this ratio is high, purchasing a home becomes more attractive compared to renting, increasing demand for homeownership. Conversely, when the ratio is low, renting becomes a more attractive option. First-tier cities generally have lower Price-to-Rent Ratios compared to second-tier cities. This is primarily due to their stronger economic development, higher population density, and elevated housing prices. As shown in Figure 1, the rental yields in Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, and Shenzhen were 1.48%, 1.75%, 1.68%, and 1.64%, respectively as of May 2024. Notably, apart from Beijing, the rental yields in the other three first-tier cities have surpassed their previous peak levels recorded in 2019 [7].

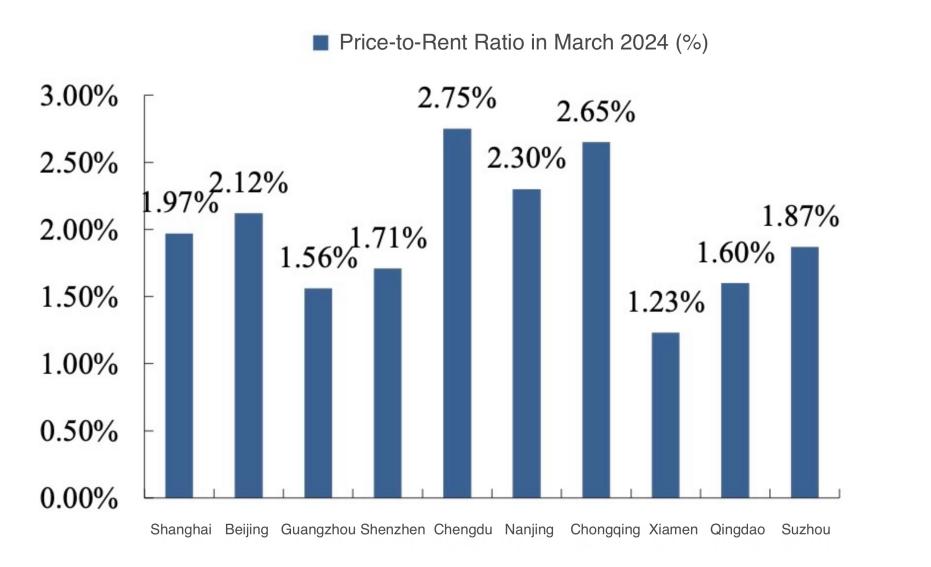

Figure 2: The Price-to-Rent Ratio of major Chinese cities in March 2024 (data from: wind, Soochow Securities)

Figure 2 shows a comparison for the Price-to-Rent Ratio between first-tier cities and second-tier and lower-tier (for example, third- and fourth-tier cities) in China [8]. In first-tier cities such as Beijing and Shanghai, where housing demand remains strong, policy interventions tend to have a more immediate and pronounced effect. In contrast, housing price are more closely linked to local economic growth and population dynamics in second-tier cities like Chengdu and Chongqing. Following the removal of China’s home purchase restrictions in the third quarter of 2024, the real estate market did not experience the expected recovery. Instead of stabilizing, housing prices continued to decline, particularly in second- and third-tier cities, as well as in smaller urban areas. There are studies indicating that some of these cities are facing an oversupply of housing, where new construction has outpaced demand [9]. The combination of increased housing supply and population outflows has resulted in excessive inventory, weakening market momentum and limiting the potential for price increases.

3.2. The impact of Chinese policy adjustment

An interesting and somewhat counterintuitive phenomenon following the removal of home purchase restrictions is that housing prices in the most central areas of major cities have risen rather than declined. This trend has been particularly evident in first-tier cities, where high-income individuals have significantly increased their purchasing power. As housing prices increase, middle- and lower-income families often find it increasingly difficult to afford homes in central areas, pushing them toward suburban districts or second-tier cities. In contrast, high-income households continue to acquire premium properties in prime locations with relative ease. At the core of this phenomenon lies a severe imbalance in supply and demand. Land availability in the central districts of first-tier cities is highly constrained, making it difficult to meet the continually growing demand for housing. The concentration of both population and capital in these areas has led to persistent supply shortages. Even with the relaxation of purchase restrictions, the limited increase in housing supply has been insufficient to accommodate rising demand. As a result, prices have continued to escalate, driven by the fundamental supply-demand imbalance. This trend has broader implications for economic inequality and regional disparities in China. While a booming real estate market contributes to economic growth, excessive increases in housing prices can also exacerbate structural imbalances and intensify social tensions.

To address these challenges, the Chinese government must implement effective measures to regulate the supply-demand dynamics of the housing market, promote balanced economic development, and ensure adequate housing accessibility for middle- and lower-income groups to foster social stability and equity.

4. Japan’s real estate market

In Japan, the influence of interest rates on the real estate market is closely tied to their interaction with exchange rate fluctuations. These two factors are interrelated and collectively shape Japanese market dynamics. Focusing on the period following the accumulation of Japan’s real estate bubble (1956–1989), a pivotal turning point occurred in May 1989, when the Bank of Japan (BOJ) raised the official discount rate from 2.5% to 3.25% as part of a contractionary monetary policy [10].This adjustment signaled the beginning of a slowdown in Japan’s real estate market. Over the following year, in an effort to curb economic overheating and speculative activity in the property sector, the BOJ implemented multiple interest rate hikes. By August 1990, the official discount rate had surged to 6%, a level that severely undermined market confidence and leading to reduced investment activity [11]. As capital outflows increased, investor sentiment deteriorated ultimately contributing to Japan’s prolonged economic stagnation, often known as Japan’s “Lost Two Decades.”

For both domestic and international buyers, higher interest rates meant higher mortgage costs. The increased borrowing expenses forced many local buyers to delay or abandon their pervious housing purchase plans, exacerbating the cooling trend in Japan’s real estate market activities.

4.1. The impact of rising interest rates

With rising interest rates, Tokyo’s real estate market provides a relevant case for our analysis. As Japan’s capital and economic hub, Tokyo has a strong labor market, higher levels of economic development, and a dense population. These factors contribute to a more dynamic real estate market compared to cities such as Osaka and Kobe, with consistently strong housing demand.

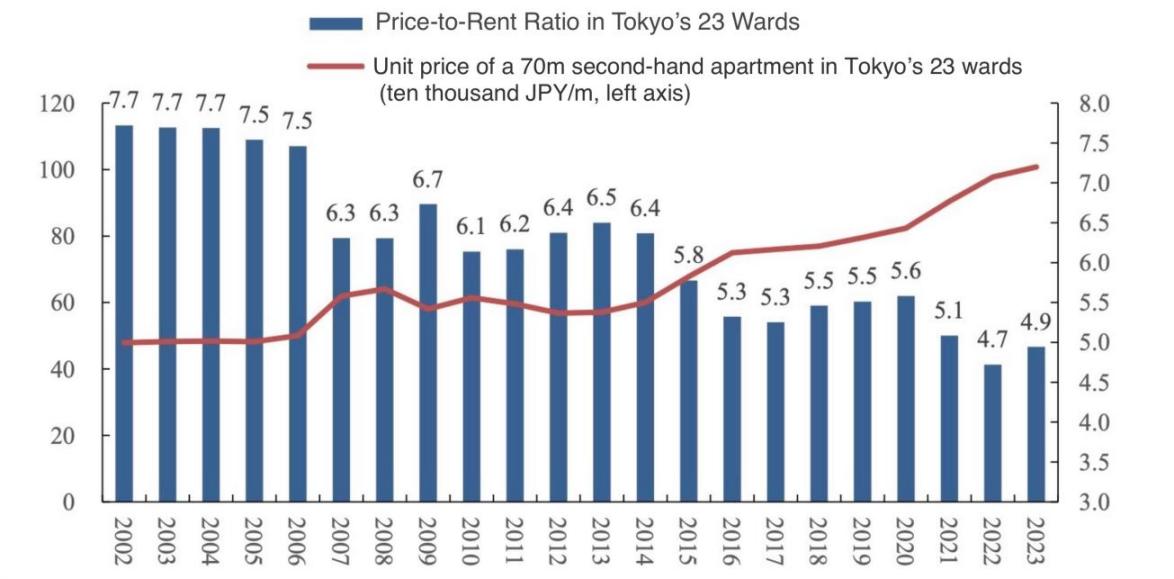

Rental yields in Tokyo’s 23 wards exhibit observable trends in response to interest rate fluctuations, as illustrated in Figure 3. The rental yield for standard apartments in Tokyo’s 23 wards was 7.7% in 2002. The returns remained attractive even after deducting holding costs of approximately 1.2% to 1.5%, thus it has attracted a number of investments from real estate private equity funds based in Singapore, Europe, and North America [12]. However, over the past two decades, rental yields have declined steadily and reaching 4.9% in 2023.This decline reflects a broader trend of diminishing investment returns in Tokyo’s real estate market, particularly in the context of rising interest rates. A decline in rental yields not only reflects lower income for investors but also indicates potential pressures for market adjustments. In a high-cost property market like Tokyo, where many homebuyers rely on mortgage financing. As interest rates increase their mortgage costs, which place a greater financial strain on potential buyers. Higher mortgage expenses reduce the affordability and may discourage some prospective buyers from entering the market, leading to a decline in transaction volumes and a slowdown in overall market activity.

Figure 3: Rental yield in Tokyo’s 23 wards from 2002 to 2023 (data from: Tokyo Kantei, Soochow Securities)

These effects are particularly evident in Japan, because of the stagnating population growth and an aging demographic have contributed to weakening housing demand. In response, sellers may need to adjust pricing strategies to align with shifting market conditions, potentially resulting in slower or even declined price growth rate. As a result, some potential homebuyers may delay purchasing decisions and instead opt for long-term rentals which increases the demand in the rental market. This trend could place upward pressure on rental prices, especially in areas with concentrated rental demand, such as Tokyo’s central districts and other major metropolitan areas.

A decline in rental yields may prompt investors to reconsider their asset allocation strategies. As returns diminish, some investors may reallocate capital toward alternative investment opportunities offering more competitive returns, such as financial markets or overseas real estate. Altering the market’s financing structure and potentially contributing to downward pressure on property prices, these shifts in capital flows could result in an outflow of funds from Tokyo’s real estate market.

4.2. Exchange rate fluctuations and Japanese policy adjustment

During this period, fluctuations in Japan’s exchange rate also played a significant role in shaping the real estate market. The continuous appreciation of the Japanese yen weakened the international competitiveness of Japanese exports, which places the pressure on the country’s export-driven economic structure and contributing to broader economic challenges. As the yen appreciated, the rising exchange rate increased the cost of converting foreign currencies into yen for investment, making Japanese real estate less attractive to overseas investors. This decline in foreign capital inflows contributed to a contraction in demand within the real estate market. Thus, the combined effects of interest rate adjustments and exchange rate fluctuations played the key roles in shaping the prolonged stagnation of Japan’s real estate sector from the 1990s.

Recognizing the challenges posed by these economic shifts, the Japanese government and the BOJ reassessed the interaction between monetary policy and real estate market stability. This shift in approach became more evident in the 21st century, especially in the aftermath of the 2008 Global Financial Crisis, when policymakers adopted a more cautious and flexible monetary strategy to prevent a recurrence of past market instability. In April 2013, the BOJ introduced Qualitative and Quantitative Monetary Easing (QQE), a policy aimed at increasing market liquidity and lower funding costs through large-scale purchases of government bonds and other financial assets [13]. By lowering borrowing costs, such low-interest-rate environment was expected to encourage borrowing and investment, theoretically stimulating real estate market being actively. However, despite the sustained large-scale bond purchases by the BOJ, Japan’s inflation rate has remained below the 2% target level as of January 2025 [14]. Moreover, while these measures have influenced market conditions, lingering concerns from the collapse of the earlier real estate bubble continue to affect local homebuyers. As a result, investor and consumer confidence in the real estate market has become slowly to recover.

5. Comparison between China and Japan’s real estate market

The real estate markets of China and Japan are similar, yet distinct. They have both experienced the rapid expansion periods followed by the bursting of market bubbles, which influenced by fluctuations in interest rates, differences in governments’ policy interventions, and their respective economic states, as well as their own historical background of real estate bubbles.

5.1. Real estate bubble formation

The formation mechanisms of real estate bubbles in China and Japan exhibit fundamental differences. In China, the real estate bubble has been primarily policy-driven. Over the past two decades, China’s real estate sector has expanded rapidly, with its bubble fueled by local governments’ reliance on land-based fiscal revenue, extensive credit availability stimulating housing demand, and speculative investment activity. In certain cities, property prices have surged at a rate far exceeding household income growth, exacerbating market imbalances.

Whereas in Japan, it was largely driven by global financial dynamics. Particularly following the 1985 Plaza Accord, which led to a sharp appreciation of the Japanese yen. This currency shift combined with prolonged credit easing and a surge in foreign capital inflows, caused property prices far beyond their fundamental economic values. During the 1980s, commercial land prices in Japan appreciated at a much higher rate than residential land values, with major metropolitan areas, such as Tokyo and Osaka, experiencing extreme overvaluation. The eventual collapse of this bubble resulted in a prolonged economic downturn, commonly referred to as the “Lost Two Decades.”

5.2. Variations in market investment returns

China and Japan’s return on investment (ROI) in the real estate sector following financing difference. In China, a high-interest-rate environment has constrained returns on property investments, as elevated borrowing costs have diminished profitability. Conversely, Japan’s longstanding low-interest-rate policies have supported a relatively stable investment return, estimated at approximately 4%. Moreover, Japan’s implementation of low interest rates and QQE initially stimulated housing price growth by lowering financing costs. However, this approach has encountered structural limitations in the long run, as broader economic conditions and demographic shifts have exerted a stronger influence on market stability. This suggests that monetary policy alone is insufficient to sustain real estate market recovery, highlighting the need for structural adjustments in economic planning and housing policies to sustain long-term market growth.

5.3. Policy adjustments

Although the Chinese and Japanese governments adopted different regulatory strategies in response to the bursting of their respective real estate bubbles, both experienced delays in policy adjustments. As a result, prolonged stagnation in the property market remains a shared characteristic lasting between two to three decades.

In China, a series of policy adjustments were introduced to curb speculative overheating in the housing market. These included purchase restriction policy, higher mortgage interest rates, and adjustments to land finance. While these interventions succeeded in tempering rapid price escalation, they also reduced market liquidity and dampened overall real estate activity. A fundamental feature of China’s property system, the state-controlled land system which supports urbanization and infrastructure development, has led to regional disparities in land supply, contributing to market imbalances. Additionally, an oversupply of housing in many second- and third-tier cities has resulted in rising inventory accumulation level, which in turn weakens future demand. In the short term, local governments have continued to rely on land sales as a primary revenue source; but in the long run, an over-reliance on land-based fiscal revenue may weaken their financial sustainability. Furthermore, China’s housing policy emphasizing residential use over speculative investment has reinforced the residential function of real estate while diminishing its role as a financial asset, thereby reducing market liquidity and investment appeal.

In contrast, Japan operates under a private landownership, where supply and demand mechanisms primarily regulate land allocation, with minimal government intervention. While this system allows for greater flexibility in land transactions, Japan’s policy response to its real estate crisis was marked by delayed intervention. Intervention remained limited during the speculative boom, but after the bubble collapsed, policymakers implemented a series of aggressive monetary policies, including aggressive interest rate hikes and strict credit controls, later followed by low interest rates and QQE. These sudden policy reversals triggered a sharp market contraction, leading to a rapid decline in housing prices and broader economic repercussions. Furthermore, rising interest rates weakened Japan’s export competitiveness exacerbating the economic stagnation. Consequently, Japan’s real estate market has remained mired in long-term stagnation, with limited prospects for a sustained recovery.

5.4. Supply-demand imbalances

Although China and Japan’s real estate markets analogous in structural imbalances, they are distinct in the causes of supply and demand mismatch. China’s primary challenge lies in supply-side excess, particularly in second- and third-tier cities, where excessive housing supply has outpaced the demand leading to persistent price declines. Major metropolitan areas have maintained greater price stability because its strong economic activity and continuous population inflows. Consequently, the future trajectory of China’s real estate market will be influenced not only by monetary policy adjustments but also by urbanization trends, demographic shifts, and industrial restructuring.

However, Japan faces a demand-side contraction. As an aging population and declining birth rates have led to a diminished housing demand. Older generations have reduced housing needs, while younger individuals who burdened by economic pressures and employment uncertainties, demonstrated weaker purchasing intentions. With a persistent supply-demand imbalance has made price recovery increasingly difficult, this persistent demographic trend has contributed to prolonged stagnation in Japan’s real estate market.

Given all these differences above, China’s real estate market retains some capacity for adjustment, whereas Japan faces greater structural constraints with demand continuing to weaken over the long term. These interacting factors have shaped the distinct trajectories of real estate development in the two countries.

6. Conclusion

The primary objective of this paper is to analyze the impact of interest rate adjustments on real estate markets in China and Japan, exploring how shifts in monetary policy interact with distinct institutional frameworks and supply-demand dynamics to influence housing prices. Additionally, this paper makes a comparison through four different aspects between two countries due to interest rate adjustments.

The analysis of decreasing interest rates in China reveals that the reason for high property prices but with low rental yields in major urban centers is the persistent supply-demand imbalances, based on a comparison of price-to-rent ratios in first- and second-tier cities. This trend has contributed to economic disparities, income inequality, and structural imbalances within the broader economy, intensifying social tensions and financial risks. In contrast, the study of rising interest rates in Japan demonstrates that as increased mortgage rates have further suppressed real estate activity. Simultaneously, higher interest rates have weakened its exports international competitiveness, further dampening economic growth. Additionally, the lingering effects of the past real estate bubble collapse continue to erode investor and consumer confidence, resulting in a prolonged recovery cycle for the real estate market.

Thus, this paper emphasizes that only monetary adjustments cannot fully resolve long-term structural challenges, though interest rate policies are essential tools for regulating real estate markets. Therefore, the government needs to adopt a more comprehensive policy framework, integrating industrial restructuring, population mobility strategies, and fiscal policy measures to promote market equilibrium and economic stability. In China, in order to correct structural inefficiencies, future policy should focus on balancing the land supply, improving population mobility and strengthening the rental market, as well as reducing fiscal dependence on real estate. Furthermore, addressing affordable housing accessibility for middle- and low-income groups is critical to ensuring social cohesion and long-term economic stability. However, there are still three key challenges need to consider by government, namely how to manage speculative risks, to find the way to guide market adjustments effectively, and to reduce excessive reliance on real estate as a primary economic driver. For Japan, where prolonged market stagnation has constrained economic growth, comprehensive population policies and restructuring on property market and industry are necessary to counter the decline in demand for homeownership and to promote long-term market recovery.

References

[1]. Lin, X., Shi, Y., and Wang, M. (2014) On the Impact of Interest Rate Fluctuation on the Housing Prices in the Framework of Partial Balance Analysis, 46(1), 128.

[2]. Ito, T. I. and K. Rose, A. (2006) Monetary Policy with Very Low Inflation in the Pacific Rim. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

[3]. Lu, L. (2017) The Study of the Influential Factors of China’s Real Estate Price. Advances in Social Sciences, 06(08), 1071–1078.

[4]. Kerr, D. (2002) The ‘Place’ of Land in Japan’s Postwar Development, and the Dynamic of the 1980s Real-Estate ‘Bubble’ and 1990s Banking Crisis. Environment and Planning. D, Society & Space, 20(3), 345–374.

[5]. Wakatebe, M. (2012) Japan’s “Lost Two Decades” and ‘fiscal Crisis.” SERI Quarterly (Seoul), 5(2), 41-43.

[6]. He, Y. (2025) Monetary Policy Implementation Report of China for Q4 2024 2024. Retrieved from www.gov.cn website: https://www.gov.cn/lianbo/bumen/202502/content_7003589.htm

[7]. Fang, C., Xiao, C. and Bai, X. (2024) Seeing Through the Flames: How to Anticipate and Identify Turning Points in the Real Estate Market. SOOCHOW Securities Research Reports—In-depth Industry Reports—Real Estate, 2024(7), 1-19.

[8]. Fang, C., Xiao, C. and Bai, X. (2024) Land Acquisition in the Real Estate Sector: What Expectations Should We Have and What Will Be the Outcomes?. SOOCHOW Securities Research Reports—In-depth Industry Reports—Real Estate, 2024(6), 1-25.

[9]. Liow, K. H. and Newell, G, (2012) Investment Dynamics of the Greater China Securitized Real Estate Markets. The Journal of Real Estate Research, 34(3), 399 – 428.

[10]. Bank of Japan. (2017) Financial System Report. Retrieved from https://www.boj.or.jp/en/research/brp/fsr/fsr170419.htm

[11]. Cline, W., Kenneth, K., Posen, A. S. and Schott, J. J. (2014) Lessons from Decades Lost: Economic Challenges and Opportunities Facing Japan and the United States. Peterson Institute for International Economics Briefing, 14-4.

[12]. Fang, C., Xiao, C. and Chen, L. (2024) Japan’s Real Estate Market Poised for Significant Uptrend. SOOCHOW Securities Research Reports—In-depth Industry Reports—Real Estate, 2024(4), 1-16.

[13]. Kozo, H. and Toshiki, J. (2023) The effects of quantitative easing policy on bank lending: Evidence from Japanese regional banks, Japan and the World Economy. Japan and the World Economy, 67, 101193.

[14]. Hausman, J.K. and Wieland, J.F. (2015) Overcoming the Lost Decades? Abenomics after Three Years. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Fall 2015, 385-413.

Cite this article

Shi,Z. (2025). The Impact of Interest Rate Adjustments on Real Estate Prices in China and Japan. Communications in Humanities Research,60,72-80.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Literature, Language, and Culture Development

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Lin, X., Shi, Y., and Wang, M. (2014) On the Impact of Interest Rate Fluctuation on the Housing Prices in the Framework of Partial Balance Analysis, 46(1), 128.

[2]. Ito, T. I. and K. Rose, A. (2006) Monetary Policy with Very Low Inflation in the Pacific Rim. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

[3]. Lu, L. (2017) The Study of the Influential Factors of China’s Real Estate Price. Advances in Social Sciences, 06(08), 1071–1078.

[4]. Kerr, D. (2002) The ‘Place’ of Land in Japan’s Postwar Development, and the Dynamic of the 1980s Real-Estate ‘Bubble’ and 1990s Banking Crisis. Environment and Planning. D, Society & Space, 20(3), 345–374.

[5]. Wakatebe, M. (2012) Japan’s “Lost Two Decades” and ‘fiscal Crisis.” SERI Quarterly (Seoul), 5(2), 41-43.

[6]. He, Y. (2025) Monetary Policy Implementation Report of China for Q4 2024 2024. Retrieved from www.gov.cn website: https://www.gov.cn/lianbo/bumen/202502/content_7003589.htm

[7]. Fang, C., Xiao, C. and Bai, X. (2024) Seeing Through the Flames: How to Anticipate and Identify Turning Points in the Real Estate Market. SOOCHOW Securities Research Reports—In-depth Industry Reports—Real Estate, 2024(7), 1-19.

[8]. Fang, C., Xiao, C. and Bai, X. (2024) Land Acquisition in the Real Estate Sector: What Expectations Should We Have and What Will Be the Outcomes?. SOOCHOW Securities Research Reports—In-depth Industry Reports—Real Estate, 2024(6), 1-25.

[9]. Liow, K. H. and Newell, G, (2012) Investment Dynamics of the Greater China Securitized Real Estate Markets. The Journal of Real Estate Research, 34(3), 399 – 428.

[10]. Bank of Japan. (2017) Financial System Report. Retrieved from https://www.boj.or.jp/en/research/brp/fsr/fsr170419.htm

[11]. Cline, W., Kenneth, K., Posen, A. S. and Schott, J. J. (2014) Lessons from Decades Lost: Economic Challenges and Opportunities Facing Japan and the United States. Peterson Institute for International Economics Briefing, 14-4.

[12]. Fang, C., Xiao, C. and Chen, L. (2024) Japan’s Real Estate Market Poised for Significant Uptrend. SOOCHOW Securities Research Reports—In-depth Industry Reports—Real Estate, 2024(4), 1-16.

[13]. Kozo, H. and Toshiki, J. (2023) The effects of quantitative easing policy on bank lending: Evidence from Japanese regional banks, Japan and the World Economy. Japan and the World Economy, 67, 101193.

[14]. Hausman, J.K. and Wieland, J.F. (2015) Overcoming the Lost Decades? Abenomics after Three Years. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Fall 2015, 385-413.