1. Introduction

In John Ashbery’s poem A Blessing in Disguise (selected from poetry collection Rivers and Mountains), a large number of personal pronouns are dispatched, with the use of “you” and “I” being particularly innovative. The use of personal pronouns is a crucial entry point for understanding his poetry. In Ashbery's poems, the shifting and ambiguous use of personal pronouns often poses comprehension challenges for readers. At its core, this is due to his multiple denotations. Each possible denotation contributes to a level of meaning in the poem, and these dimensions interweave each other, enhancing emotional expression or creating conflicting oppositions. The interwoven and interdependent nature of pronouns allows readers to examine the poet's complex inner emotions from a more diverse perspective, fostering a broader and richer emotional resonance.

2. Literature review

Marjorie Perloff, one of the most classic critics on John Ashbery’s poetry, utilizes the term “Indeterminacy” to describe the techniques and meaning represented in his poems. Apropos John Ashbery, she interprets his indeterminacy as “mysteries of construction”. The techniques adopted by John Ashbery have contributed to the inscrutability of his poetry, for instance, the loose blank verse, the frequent shift of pronouns, and the reality-dream-reality structure. In his poetry, the article of person can be used to refer to anyone: “ ‘I’, ‘we’ and ‘you’ may well refer to the poet himself” [1].

Vincent [2] also finds the specificity of “you” in John Ashbery’s works. In his monograph John Ashbery and You in 2007, he makes a thorough research upon the distribution of “you” in most of Ashbery’s collections, and further points the complex functions and their effects of “you” on the relationship between readers and texts. This article mainly refers to Vincent’s article in 2006.

AbdelFattah [3] focuses on the permutation in Ashbery’s strata poems, in which he categorizes three effects relating to this technique: psychological effect, geometric effect, and graphosyntatic effect. All these effects are reached via Ashbery’s poetic techniques such as the shift of tenses and personal pronouns, the use of punctuation, and added clauses.

Zhang & Peng [4] expound the Derridean deconstructive writing in Ashbery’s poem “Self-Portrait in a Covex Mirror”, in which the shift of signifier in his poems creates endless interpretations. The transferring between multiple views and identities extends its meaning into infinity, thus no definite signified can be traced in his poems.

Above all, a question comes to the surface that how should we readers reach to his poetry via his versatile poetic techniques? This article will present a cognitive poetic analysis upon his poem A Blessing in Disguise, analysing the presentment of the personal pronouns “you” and “I” in order to uncover the cognitive process of readers generating their understanding.

3. Background

All these researches have made clear the deployment of personal pronouns contributes to the opaqueness of his poetry, which might cause special effects upon the readers. Considering the link between his poems and the cognitive process, the approach of interpreting his poetry via cognitive poetic theory might be feasible.

In traditional cognitive linguistic theories, the linguistic symbols are the combination of both the form and the meaning. The aim of cognitive linguistics is to find the relationship between our cognition and the linguistic symbols as well as the way our thinking patterns are being presented in language expressions. However, things go slightly different when it comes to post-modernism poetry, following Ashton’s implication [5] that traditionally the openness of the text, the participation of the reader, and the indeterminacy of the meaning differentiate postmodern poetry from modern one. In response to this, Ashbery always exhibits in his poems fragmented images one by one, seemingly illogical as well as incoherent. Apropos our way of thinking, this supposition still makes sense, which all lead to the cognitive analysis challenging. Nevertheless, there are still researches upon Ashbery pertaining to the cognitive dimension.

The most representative research of applying cognitive theories into John Ashbery’s poetry can be seen in Kherbek’s doctoral dissertation [6]. He argues the interrelation between Ashbery’s poetry and cognitive theories in total four chapters among which the first two chapters utilize syntactic theory, and cognitive “theory of context” writing to examine Ashbery’s poetic writing, revealing the cognitive relations presented in his poetry. The last two chapters “consider cognitive questions using Ashbery’s poetry as a means of entry into controversial areas in formal cognitive studies”.

4. Theoretical framework

This research adopts the cognitive poetic theory of “literary resonance” developed mainly by Peter Stockwell [7-8]. As he explains this term:

“The notion of resonance is commonly encountered in non-scholarly readers’ comments about their own experiences of literary reading. Texts resonate if they persist in the memory long after the actual physical reading has taken place. Resonance is a feeling of the affective power of an encounter with a piece of literature. It is vague and subjective, it is both psychological and socially mediated, and it is a metaphor whose target is intangible and whose source is impressionistically understood: for all these reasons, it is a difficult concept to pin down, and it is a concept that is avoided in scholarly discussions. This makes it an intriguing and attractive notion for cognitive poetic exploration” [7]: 28, [8]: 76.

This theory posits itself in the attention-perception basis, developing a cognitive-literary approach of analyzing literature. Readers’ standpoint is center to this model. Postmodernism literature possesses an open text, and this also falls into John Ashbery’s poetry. The openness to readers composes an important dimension of appreciation as well as analysis. Therefore, the theory of resonance provides with a novel perspective to deepen the understanding upon the readers’ effect.

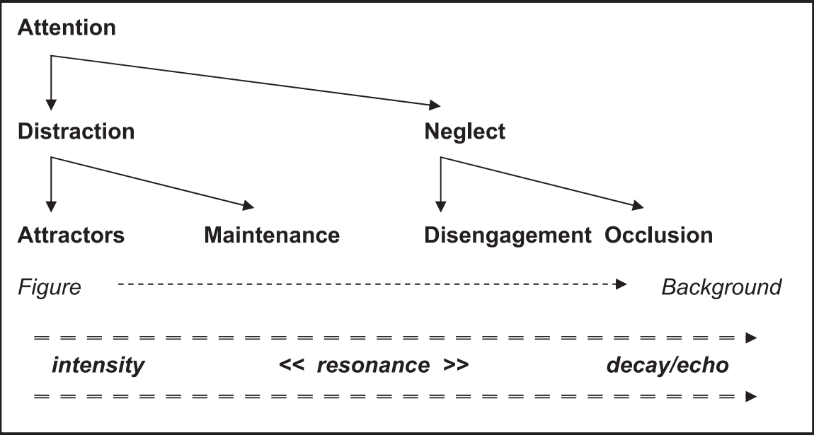

Figure 1: A general model of attention-resonance [7]: 29

Figure 1 shows a general model of attention-resonance. Readers attention gets distracted by attractors. The attractor, according to Stockwell, “is a conceptual effect rather than a specific linguistic feature” [7:29]. It remains prominence through maintenance, which, according to Stockwell, can be the sustaining of focus, or the non-shift devices. These prominent parts form the traditional concept of “figure” in cognitive linguistics. “Certain elements in a visual field are selected for attention, and these will typically be the elements that are regarded as figures” [8:75].Elements being rendered hidden from the focus are what being neglected. When attractors are deprived of maintenance, it is in the state of disengagement. When an attractor is explicitly wiped out of attention, through negation or other approaches, and being occluded by an alternative one, a new attractor appears and the model starts from the beginning. These non-prominent part constructs the ground, responding to figure. In this sense, the alternation of attractors is being reached via the shift of attention.

All these explanations form the continuum of literary resonance from intensity (prominent figures on the left side) to decay / echo (non-prominent ground on the right side). This model reveals the inner interaction between figure and ground, presenting a dynamic schema of readers’ cognitive pattern of attention-resonance.

5. Discussions on the poem’s cognitive processing

The term pluralism has been adopted in present article to further discover new interpretation on it. This term mainly refers to the possible plural interpretations upon John Ashbery’s poetry.

5.1. Discussions on the poem’s attractor and maintenance

In Ashbery’s poetry, one can always discover the shift among different personal pronouns. The twisting of identities brings bewilderment in our focuses, in that it leads to the misguided maintenance of its correspondent attactor. In Stockwell’s model, the attractors being neglected are set offstage (which is the ground part when it comes to the schematic mode of figure-ground) during the cognitive process, though it can be reactivated. In this way, when one voice is profiled, and maintained to be onstage, the other keeps silent and offstage before it is activated through distraction generated by a new attractor.

In Ashbery’s deployment of multiple identities, however, the personal pronouns, though shifted frequently, are arranged ingeniously. As he writes in A Blessing in Disguise [9]:

Yes, they are alive and can have those colors,

But I, in my soul, am alive too.

I feel I must sing and dance, to tell

Of this in a way, that knowing you may be drawn to me.

(62)

According to Stockwell, specific persons are the most highlighted type of attractor, in which speaking elements more perceivable than hearing elements. In this poem, the pronouns are easily fetched by the reader that the distance between “I” and “you” is generated. The verb “drawn” here specifies the distance and the direction of “you” coming close to “I”. The next stanza consolidates this distance that “I” and “you” are separated identities:

And I sing amid despair and isolation

Of the chance to know you, to sing of me

Which are you. You see,

You hold me up to the light in a way.

(62)

The maintenance “despair and isolation” underscores the separation of selfness, presenting “I” as an image with a strong sense of loneliness. The “you” here serves as a symbol of a savior, with its maintenance of “hold me up” and “light”. These two stanzas with their personal attractors and corresponding maintenance lay the fundamental image schema of selfness and otherness, while not be able to recognize there referents. However, if “you” are drawn to me, why “I” still feel isolated and despaired? In the third stanza, to our surprise, the relationship between these two pronouns are stated:

I should never have expected, perhaps

Because you always tell me I am you,

And right. The great spruces loom.

I am yours to die with, to desire.

(62)

A few simplest words spoil all the other assumptions built by the former stanzas. The border between “you” and “I” becomes looming, and bewildering. However, this is not the voice from “you”, instead retold by “me”. “You” and “I” appear all along the poem, there is only a single voice from “me”. The proposition that “I am you” is introduced by the stance of “you”. Then the acknowledgement is further made via “and right”. If “you” and “I” are in an integrity, then how can such lines as “I am yours to die with, to desire” and “you be drawn to me” appear? These obviously illogical maintenance underpin the dubiousness of reader to confirm the relationship between “you” and “I”. Ashbery seems not aiming to explain this, turning out to draw more questions:

I cannot ever think of me, I desire you

For a room in which the chairs ever

Have their backs turned to the light

Inflicted on the stone and paths, the real trees

That seem to shine at me through a lattice toward you.

If the wild light of this January day is true

I pledge me to be truthful unto you

Whom I cannot stop remembering.

(62)

The chairs had their backs turned to the light, with stone, paths, and real trees outside the window. A pastoral scenery is presented through a psychological image. But the word “inflicted” implies that “I” don’t want to go outside to inflict the sunlight on myself. The light, shed on things outside the window, passes through and shines on “me”. The second stanza says “you hold me up to the light in a way // I should never have expected”, and its maintenance comes in the forth stanza. “You” say to “me” that “I am you”, but the light shines at me “through a lattice toward you”. There are no chairs facing, for the chairs turned their backs to the light, but “you” are facing toward the lattice. These lines depict a contradictory scene in which “you” and “I” are of the same entity, with contrary directions; “I” refuse the light, while “you” want “me” to embrace it. All those maintenance show the reluctance of leaving “you”, but not be able to do it. Because “you” are “me”, physically, but not “me” psychologically.

Remembering to forgive. Remember to pass beyond you into the- -day

On the wings of the secret you will never know.

Taking me from myself, in the path

Which the pastel girth of the day has assigned to me.

(62)

When Ashbery writes “taking me from myself”, he seems to acknowledge that “you” equals “I”, and the latter decides to surpass the former. The selfness alienated the soul to be the “otherness” excluded from myself. “I” myself decide to escape from my soul, and lead the way with colors from “pastel girth of the day”, as the first line of this poem suggests: “I” am alive with my soul, but without those colors. How can “I” remain alive without my soul, without “you” that I am to die with? The most emotive call appears after this:

I prefer “you” in the plural, I want “you,”

You must come to me, all golden and pale

Like the dew and the air.

And then I start getting this feeling of exaltation.

(62)

These two “you” annotated by quotation marks in this line are different from those without it. They suggest the dire need of companionship as “I” pass beyond my soul. “I” am seeking the soul same as mine, and “I” want this soul. My soul cannot speak to me, while it is deeply adored by me. But with it, “I” am kidnapped by soleness just as the word “sole” shares the same pronunciation with “soul”. Images of “the dew and the air” appear in an ancient Chinese poem Que Qiao Xian which writes:

金风玉露一相逢,便胜却人间无数

(When wind and dew in gold and pure meet each other, countless in the mundane shall lose their colors.)

This line praises the love between a beloved pair, with the images “wind” and “dew”. When “I” meet the other with a desired soul, just like a pair of lovers meet each other, the exaltation at last starts waxing, as Vincent (2006: 96) discovers that this poem “has erotic generosity and charm”.

The interwoven pronouns depict Ashbery’s multiple selfness. The deployment of “you” underscores the distance between “I” and my soul. Soul in this poem is considered an individual other than the concept of selfness, though interrelated. “Desire”, “drawn”, “want” all suggest a sense of longing for what doesn’t belong to the self. When these words are assigned to “you”, the exclusiveness is therefore conveyed. The relatedness between the self (“I”) and the other (“you” or my soul) is just like a crossing-star, separated as well as intertwined. Ashbery dexterously arranges the pronouns and their maintenance, constructing a vortex of contradiction and harmonious, just like the title “A Blessing in Disguise.”

The frequent shift of attractors interrupts the shaping of the processing of figure-ground schema, resulting in not only the pluralism of his poetry, but also readers’ troublesome feelings upon it. Besides, this frequent shift also to some extent represents how poems are composed in the poet’s mind, and this process resonates with its readers, leaving them an impression of dream as well as indeterminacy.

5.2. Pluralism in the relationship between “You” & “I”

The above analysis deploys a great amount of words on the use of “you”. Based on aforementioned resonance theory, this word bears privilege to attracting the reader’s focus. However, once being captured, one is never clear about the relationship between “you” and “I”, due to the puzzling maintenance, as stated in the former chapter. The statements such as “you may be drawn to me”, and “You hold me up to the light in a way” incorporate together, demarcating the border between “you” and “I”. As the lines go on, this demarcation becomes vague and twisting, and the understanding from the reader changes, as well. “Because you always tell me I am you” tells us the fusion of two identities, with the maintenance “I am yours to die with, to desire”. As the poem comes to this stanza, the connotation of “you” is endowed with dual meanings, the one is the external deixis outside of the subject “I”, the other the internal deixis inside of the subject. The former indicates the demarcation of “you” and “I”, while the latter implies that “you” may be used to refer to “me”. This internal deixis comes to its climax when the line comes to “Taking me from myself”. “Myself” almost declares the overlap of “you” and “I”, and “my” desire to “you” drives “me” to escape from “you/myself”. Combining the emotional transformation from despair and isolation (“And I sing amid despair and isolation”) to desire (“I am yours to die with, to desire”), it can be deduced that the poet’s emotion here reaches a climax of ridding the isolation through deducting “you” from the part of mine. Hence, Ashbery says: “I prefer ‘you’ in the plural, I want ‘you’, indicating his open desire to something outside himself. The expression “ ‘you’ in the plural” can be viewed through two dimensions. First, it stands for the poet’s need of more than one person, comparing to the despair and isolation. The other comes after the poet’s erotic calling. John Ashbery belongs to sexual minorities (gay) and he once called for the ongoing well-being of this group in his early works, as Vincent points. Hence, the plural here can also refer to the sexual pluralism other than numbers more than one. At last, when the erotic partner comes to him, “I start getting this feeling of exaltation”. His dexterous practices of the polysemy and multi-deixis of words contribute greatly to the understanding of his pluralism.

5.3. Pluralism in readers’ interpretation

What exactly does the intricate deployment of pronouns bring to the readers? In fact, there shall never be a concrete and precise answer upon this question. Derrida’s concept différence reveals that meaning is always disseminating itself, leaving its trail, while interacting with others. But the ultimate goal of meaning is denied. Ashbery inherits this idea, incorporating into his writings, as Zhang & Peng [4] have suggested. Thus, the interpretations upon his poem shall in turn be in plurality, while his invitation to readers turns out to enhance this pluralism. In 4.1, the subject of the explicit deixis of “you” is not clarified, as well as cannot be. How to interpret this deixis depends on the reader’s personal experience and interpretation. At the end of 4.1, one of the possibilities is presented as his erotic partner. Moreover, it can also be viewed as the one who is reading this poetry. Apart from Ashbery’s sexual orientation, he is, fundamentally, a poet. He wants to communicate with his readers by using plain words and simple syntax. In this sense, this poem can also be read as an invitation to his readers, and his emotions presented in the poem are endowed with more meanings on different levels. His isolation, desire to “you”, and the final exaltation can be viewed as the process of reaching to his readers who understand him and gaining emotional climax. Whatever meanings the reader perceives, the situation will be righted properly, as Vincent [2:95] says: “This poem, like so many Ashbery’s, begins with untenable situation,..., and rights the situation by its close”.

6. Conclusion

John Ashbery deploys the vagueness of signifiers to create his pluralism in both the poems itself and the reader’s interpretation. Thus, there is no “right” way to understand his poetry, or in other words, any plausible interpretation upon his poetry is right. This is probably what Ashbery himself wants to convey via his oeuvres. What have been discovered are as follows: 1) he dislocation between attractors and maintenance in Ashbery’s poetry: the attractor “you” is deployed with its multi-reference function, and the word “plural” with its polysemic characteristics. Those dexterous applications contribute partly to the poem’s pluralism. 2) The readerly participation with the constructing of meaning is available, as long as its resonance accords the readers’ experience and psychology, no matter what meaning one may perceive.

The limitation lies in: This study only presents a limited vision upon cognitive poetic theory. Only a single poetry text is selected, which is too narrow to be a thorough research. In order to further on this subject, more poems shall be included, and theoretical approach needs deepening, as well.

The delimitation lies in: The starting point of cognitive-resonance theory comes from readely attention upon specific words, which, to some extent, limits the scope. There are more approaches to apply, such as phonological elements. There are more areas to explore, more barriers to exterminate.

Acknowledgement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

This article was supported by the R&D Program of Beijing Municipal Education Commission (SM202010009006).

References

[1]. Perloff, M. (1981). The poetics of indeterminacy: Rimbaud to Cage. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

[2]. Vincent, J. E. (2006). John Ashbery and you. Raritan: A Quarterly Review, 25(3), 94–111.

[3]. AbdelFattah, R. A. A. (2023). The art of permutation in John Ashbery’s str-ata poetry. Cogent Arts & Humanities, 10, 2249285. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311983.2023.2249285

[4]. Zhang, H. X. & Peng. Y. (2017). The deconstructive writings in Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror. Foreign Languages Bimonthly, 40(6), 142–149.

[5]. Ashton, J. (2005). From modernism to postmodernism: American poetry and theory in the twentieth century. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

[6]. Kherbek, W. (2014). Chinese whispers Chinese rooms: The poetry of John Ashbery and cognitive studies [D]. London: Birkbeck University of London.

[7]. Stockwell, P. (2009). The cognitive poetics of literary resonance. Language and Cognition, 1(1), 25–44.

[8]. Stockwell, P. (2020). Cognitive poetics: An introduction (2nd edition). London; New York: Routledge.

[9]. Ashbery, J. (1985). Selected poems. New York: Viking Press.

Cite this article

Zhao,X. (2025). A Case Study on the Personal Pronouns in John Ashbery’s Poem “A Blessing in Disguise”: A Cognitive Poetic Perspective. Communications in Humanities Research,66,74-80.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Literature, Language, and Culture Development

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Perloff, M. (1981). The poetics of indeterminacy: Rimbaud to Cage. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

[2]. Vincent, J. E. (2006). John Ashbery and you. Raritan: A Quarterly Review, 25(3), 94–111.

[3]. AbdelFattah, R. A. A. (2023). The art of permutation in John Ashbery’s str-ata poetry. Cogent Arts & Humanities, 10, 2249285. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311983.2023.2249285

[4]. Zhang, H. X. & Peng. Y. (2017). The deconstructive writings in Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror. Foreign Languages Bimonthly, 40(6), 142–149.

[5]. Ashton, J. (2005). From modernism to postmodernism: American poetry and theory in the twentieth century. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

[6]. Kherbek, W. (2014). Chinese whispers Chinese rooms: The poetry of John Ashbery and cognitive studies [D]. London: Birkbeck University of London.

[7]. Stockwell, P. (2009). The cognitive poetics of literary resonance. Language and Cognition, 1(1), 25–44.

[8]. Stockwell, P. (2020). Cognitive poetics: An introduction (2nd edition). London; New York: Routledge.

[9]. Ashbery, J. (1985). Selected poems. New York: Viking Press.