1. Introduction

In recent years, with the continuous development of internet technology, an increasing number of diverse social media platforms have become major participants in communication activities. Social Networking Services (SNS), with their User-Generated Content (UGC) production model, have broken the monopoly of professionals over discourse power, promoting spontaneous communication among ordinary users and fostering a space for the flourishing of niche subcultures.

As East Asian countries, China and Japan share similar cultural foundations. The languages they use have commonalities in meaning, and their social atmospheres are also more alike. This provides a natural foundation for grassroots cultural exchanges. However, similar to other communication activities, subcultures inevitably present a more localized appearance in the final decoding stage of their dissemination process.

This paper selects the "Jirai Kei" (地雷系) culture originating from Japan, as an example, tracing its history and development in both China and Japan." It is more effective to discuss subcultures on the basis of discussing society. The analysis of fictional worlds is closely related to the understanding of the real world "[1].

Most previous research has focused on the dissemination process of subcultures or the psychological challenges faced by subcultural groups [2][3][4]. Few studies have conducted detailed comparisons of a specific subculture between two countries and explored the communication activities involved.

This paper aims to provide a reference case for future cross-cultural research and to enhance the objective understanding of the "Jirai Kei" culture group by the outside world.

2. Main discussion

2.1. The history of Jirai Kei culture in Japan

The origins of Jirai Kei culture can be traced back to the term "Jirai Onna" (地雷女), a popular internet catchphrase used around 2010 on the Japanese anonymous forum 2 channel (2ちゃんねる). This term was used to describe women who appeared cute on the surface but had serious issues in intimate relationships. Due to their seemingly harmless exterior hiding a potentially destructive nature—similar to a "ticking time bomb"—they were labeled as "Jirai Onna" or "landmine women." When used to describe others, the term carries a derogatory connotation, often implying that the person suffers from mental illness.

Other similar catchphrases include "Pien-kei" (ぴえん系) and "Menhera" (メンヘラ). "Pien-kei" is widely believed to have emerged around 2018 in the Kabukicho (歌舞伎町) area, named after the popular EMOJI "Pleading Face" (ぴえん) frequently used by Japanese youth. The rise of Pien-kei girls is closely tied to Kabukicho's host club industry. Sasaki Chiwawa [5] argues that "Pien-kei girls essentially desire to be cute, but not everyone can achieve the 'mainstream' cuteness of actresses or models on TV. As a result, they gather in Kabukicho, where spending money can earn them compliments on their cuteness, and they fulfill their desires by spending on hosts." Through this behavior, which differs from traditional romantic relationships and is referred to as "oshi" (推し), they find meaning in their lives [6].

The word "Menhera" emerged around the same time as "Jirai Onna." It is a Japanese internet adaptation of the English term "mental health" and first appeared in the mental health section of 2channel. This term is most frequently used in Japanese research on Jirai Kei culture and is often associated with mental illnesses such as borderline personality disorder [7].

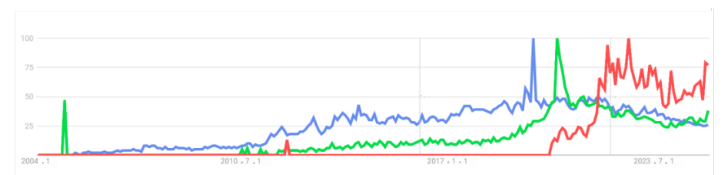

Google search data also shows that "Jirai Onna" and "Menhera" had similar search frequencies during the same period, while the search curve for "Pien-kei" clearly reflects the characteristics of a new catchphrase emerging around 2020.

Figure 1: Global search popularity of "Jirai Onna" (Blue Line), "Menhera" (Green Line), and "Pien-kei" (Red Line) from January 2004 to February 13, 2025

Although the three catchphrases—"Jirai Onna," "Menhera," and "Pien-kei"—differ in their etymology, origins, and time of emergence, they share similar meanings. All are used to describe individuals (primarily women) who appear delicate and pitiable on the surface but are emotionally unstable or mentally troubled. We collectively refer to these three catchphrases as "Jirai Kei" in the following sections.

2.2. The current state of Jirai Kei in Japan

2.2.1. Jirai Kei as a standalone fashion culture

In contemporary Japan, Jirai Kei has evolved beyond its original catchphrase to become a distinct fashion subculture. This transformation reflects the complex interplay between online identity and real-world expression of young people.

Jirai Kei is characterized by its mix of cuteness and darkness, often incorporating elements such as pastel colors, frilly dresses, and childlike accessories alongside darker motifs like crosses, bandages, and gothic-inspired details. This aesthetic serves as a visual metaphor for the inner turmoil and emotional instability associated with the Jirai Kei identity.

The rise of Jirai Kei as a fashion trend can be attributed to its resonance with individuals who feel marginalized or misunderstood by mainstream society. By adopting this style, they express their struggles with mental health, relationships, and societal pressures in a way that is both personal and communal. Social media platforms, particularly Instagram and Twitter, have played a significant role in popularizing Jirai Kei fashion, allowing individuals to share their outfits, connect with like-minded people, and build a sense of belonging. Jirai Kei as a youth subculture reflect the values of youths today and resist elements of society in a visually stimulating way [8].

However, the commercialization of Jirai Kei fashion had sparked debates. Some critics argue that the subculture's origins in mental health struggles and emotional vulnerability are being diluted as it becomes more mainstream.

2.2.2. To-yoko kids(トー横キッズ) with Jirai Kei

Next to the Toho Building in Kabukicho, there are often many young people gathered alone, wandering outside. Most of them are between 12 and 19 years old, having chosen to run away from home due to conflicts with their parents. Their numbers are so large that it has become a social phenomenon, and they are referred to by a specific term: "To-yoko kids" (トー横キッズ).

Many of these To-yoko kids are minors who have not completed their education and lack the skills to make a living, making it difficult for them to participate in regular work. To cover daily expenses, many young women turn to "sugar dating" (パパ活 ) relationships to earn money. Some girls choose to wear "Jirai Kei" fashion. This cute style not only enhances their physical attractiveness but also helps them quickly become the part of To-yoko kids community.

Many people living here have no time to plan for the future, and they can only drift through the red-light district. The culture of the red-light district subtly influences their habits. Many To-yoko kids have unhealthy practices such as drug overdose, self-harm, and prostitution [9]. These behaviors serve as desperate ways for them to cope with the harsh realities they face.

It can be said that the To-yoko kids are the group that most closely aligns with the original definition of "Jirai Onna" today, and their expressions of it have become even more extreme. This phenomenon reflects structural deficiencies in Japanese society regarding youth protection and educational support.

2.3. The development of Jirai Kei culture in China

The introduction of "Jirai Kei" to China occurred later than its emergence in Japan. Initially, it spread through anime and music, becoming integrated with otaku culture. In the early Chinese internet context, "Jirai Kei" did not carry a negative connotation but was instead seen as a "cute" associated with anime characters. The dangerous and emotionally unstable aspects of "Jirai Onna" were downplayed, transforming the image into one of a cute, well-dressed girl.

A cute example is "Menherachan", a character who gained popularity on Bilibili in 2018. Another example closer to the original meaning of "Jirai Onna" is the VOCALOID song "Venom" (ベノム), released the same year. These two distinct perceptions of Jirai Kei culture became recognized as part of “otaku culture” in China, though they had not yet fully entered the mainstream internet lexicon.

The turning point for the development of "Jirai Kei" in China came after the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2019. Compared to the past, the pandemic lockdowns brought greater mental stress, forcing the younger generation to spend more time online.

In 2022, the release of the game “NEEDY GIRL OVERDOSE” further propelled the spread of the "Jirai Onna" label in China, as the game's protagonist embodied the typical appearance and mental state of a "Jirai Onna." To cope with the pressures of daily life and seek emotional satisfaction and freedom, netizens began to freely create symbols and mock any form of rigidity [10][11]. Despite knowing that "Jirai Onna" originally carried a derogatory meaning, many people adopted self-deprecating humor to embrace and role-play as "Jirai Onna," using it as a way to accept their unchangeable reality and gain a sense of belonging online [12], forming new interest-based communities. In China, these communities are primarily rooted in social platforms with a majority female user base, such as Redbook and Weibo.

2.4. Similarities and differences between Chinese and Japanese Jirai Kei culture

Japan's "Jirai Kei" culture started as a way to categorize real-life individuals or groups, reflecting societal realities. Essentially, it evolved from offline to online but never fully detached from its red-light district roots. This connection means the culture not only emerged from the red-light district but also draws those who identify as "Jirai Onna" or "Jirai Otoko" back into that environment.

In China, "Jirai Kei" culture began online and has since taken root in major social media platforms, forming virtual communities without physical gathering spaces. Unlike in Japan, Chinese enthusiasts focus less on internal struggles and more on their social media appearance, striving to match the standard Japanese "Jirai Onna" aesthetic. In anonymous forums, criticism often targets photos for having a "China style" (中味), citing issues like body shape, light makeup, or skin tone that deviate from the traditional "Jirai Onna" look. A brand hierarchy has also emerged, with Japanese labels favored over local ones, despite their higher cost.

While Japanese "Jirai Onna" culture initially aimed to attract male attention and build relationships, its Chinese counterpart has blended with radical feminist ideas. Many Chinese "Jirai Onna" reject men entirely, criticizing them solely for their gender, even if they show interest in the culture. As a result, men are often excluded from participating or speaking in these communities.

3. Conclusion

Despite the many differences between Chinese and Japanese Jirai Kei cultures, there is one key similarity: just as Jirai Kei culture is gaining popularity in China, its prominence in Japan has also been rising in recent years. The resurgence of Jirai Kei culture symbolizes a shared societal pressure in both countries—unhappy family environments and overly competitive, "involutionary" social systems have forced young people, who feel unable to participate in this competition, to choose a path of rebellion. Through social media, ordinary people are exposed to a broader world and more possibilities, but the stark contrast between the idealized hologram of happiness online and the harsh realities of life creates a sense of helpless disconnection. Identifying with pre-modern subcultures may be a way to seek security and escape reality.

We need more unbiased understanding to clarify the root causes of these phenomena. It is hoped that future research will provide opportunities to delve deeper into the lives of Jirai Kei communities in both China and Japan, exploring how cultural dissemination operates and how geographical, economic, and political factors have shaped the same external culture into different core identities.

References

[1]. Uno Tsunehiro(2018). Lecture Notes on Subculture Theory for Young Readers

[2]. Kawamura, Yuniya. "Fashioning Japanese Subcultures." (2013): 1-192.

[3]. Seko Y, Kikuchi M. Mentally ill and cute as hell: Menhera girls and portrayals of self-injury in Japanese popular culture[J]. Frontiers in Communication, 2022, 7: 737761.

[4]. Kose Yunia and Matsumoto Takuma. "Toward schools where reciprocal help is possible:The influence of attitudes toward ‘Menhera’ on help-seeking".Annual report of the Faculty of Education, Gifu University. Humanities and social science 72(1):2023,p.155-164.

[5]. Sasaki, Chiwawa,”The Disease Called "Pien": Consumption and Validation in the SNS Generation.”(2021)

[6]. Shūkan Bunshun(2022).What’s the Difference Between "Pien-kei Girls, " "Jirai-kei Girls, " and "Mass-Produced Girls"? A Former Host Club Enthusiast Female College Student Talks About the Reality of Kabukicho and Gen Z.Available at: https://bunshun.jp/articles/-/51425?continueFlag=4f9f73bd848c7680e8a79370187455f0/ (Accessed: 15 February 2025).

[7]. Terada, H. and Watanabe, M. (2021). A study on the history and use of the word “Menhera.” [Japanese] Hokkaido University Bull. Counsel. Room Dev. Clin. Needs 4, 1–16.

[8]. Park, Judy. "An investigation of the significance of current Japanese youth subculture styles." International Journal of Fashion Design, Technology and Education 4.1 (2011): 13-19.

[9]. Masuya Jirou. (2023)“Tōyoko Kids” and Psychiatry). In Proceedings of the 54th Annual Conference on Mental Health and Society, pp. 14–19. Japan Society for Mental Health.

[10]. Shi, Lei.(2017). Powerlessness, Decadence, and the Dissolution of Resistance—An Interpretation of the Online "Sang Culture" Phenomenon, Journal of FuJian Normal University (Philosophy and Social Sciences Edition).2017, (06).pp, 168-174+179.

[11]. XiaoJing, Li (2025)(Ideological Concerns and Governance Pathways of the "Two-Dimensional" Subculture [J].Education Review, 2025, (02):37-46.

[12]. Sano Atusi, (2023) Jirai Onna are proliferating among Chinese Z generation.Available at: https://note.com/sano2019/n/na5878f205cf8 (Accessed: 14 February 2025).

Cite this article

Sun,R. (2025). An Examination of the History and Current State of Jirai Kei in China and Japan. Communications in Humanities Research,69,9-13.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Literature, Language, and Culture Development

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Uno Tsunehiro(2018). Lecture Notes on Subculture Theory for Young Readers

[2]. Kawamura, Yuniya. "Fashioning Japanese Subcultures." (2013): 1-192.

[3]. Seko Y, Kikuchi M. Mentally ill and cute as hell: Menhera girls and portrayals of self-injury in Japanese popular culture[J]. Frontiers in Communication, 2022, 7: 737761.

[4]. Kose Yunia and Matsumoto Takuma. "Toward schools where reciprocal help is possible:The influence of attitudes toward ‘Menhera’ on help-seeking".Annual report of the Faculty of Education, Gifu University. Humanities and social science 72(1):2023,p.155-164.

[5]. Sasaki, Chiwawa,”The Disease Called "Pien": Consumption and Validation in the SNS Generation.”(2021)

[6]. Shūkan Bunshun(2022).What’s the Difference Between "Pien-kei Girls, " "Jirai-kei Girls, " and "Mass-Produced Girls"? A Former Host Club Enthusiast Female College Student Talks About the Reality of Kabukicho and Gen Z.Available at: https://bunshun.jp/articles/-/51425?continueFlag=4f9f73bd848c7680e8a79370187455f0/ (Accessed: 15 February 2025).

[7]. Terada, H. and Watanabe, M. (2021). A study on the history and use of the word “Menhera.” [Japanese] Hokkaido University Bull. Counsel. Room Dev. Clin. Needs 4, 1–16.

[8]. Park, Judy. "An investigation of the significance of current Japanese youth subculture styles." International Journal of Fashion Design, Technology and Education 4.1 (2011): 13-19.

[9]. Masuya Jirou. (2023)“Tōyoko Kids” and Psychiatry). In Proceedings of the 54th Annual Conference on Mental Health and Society, pp. 14–19. Japan Society for Mental Health.

[10]. Shi, Lei.(2017). Powerlessness, Decadence, and the Dissolution of Resistance—An Interpretation of the Online "Sang Culture" Phenomenon, Journal of FuJian Normal University (Philosophy and Social Sciences Edition).2017, (06).pp, 168-174+179.

[11]. XiaoJing, Li (2025)(Ideological Concerns and Governance Pathways of the "Two-Dimensional" Subculture [J].Education Review, 2025, (02):37-46.

[12]. Sano Atusi, (2023) Jirai Onna are proliferating among Chinese Z generation.Available at: https://note.com/sano2019/n/na5878f205cf8 (Accessed: 14 February 2025).