1. Introduction

Italy, Rome: The Pantheon, a cultural icon in the heart of Rome, an architectural marvel for all to see, and a historical symbol carrying centuries of history with it, is unrivalled in its grandeur. This historical symbol, steeped in centuries of rich history, showcases the ingenuity and artistry of ancient Roman engineering. With its magnificent dome and striking portico, the Pantheon not only embodies the grandeur of classical architecture but also serves as a testament to the enduring legacy of Roman civilization [1]. However, as we move further into the modern era, the Pantheon has undergone significant transformations that reflect broader societal changes. From its original function as a temple dedicated to the gods to its current role as a church and tourist attraction, the Pantheon has adapted to the evolving needs and values of society. These changes serve as essential context to consider regarding the preservation of historical integrity and the impact of modernization on cultural heritage. This essay explores the various ways in which the Pantheon has changed over time, examining how contemporary influences have shaped its role and significance in today's world, while also considering the challenges and opportunities that arise in the preservation of such an iconic monument. This exploration helps us gain a deeper understanding of how the Pantheon continues to resonate with both locals and visitors, bridging the past and present in a rapidly changing world.

2. Cultural and historical context

Entering the Piazza della Rotunda in Rome, packed full of vendors and tourists, the first thing you see is the towering obelisk in the marble fountain [2]. Centred right in the square, the 16th-century fountain is a prelude to what stands at the front of the square in all its domed glory, the Pantheon. As you approach the Pantheon, the exterior presents a striking blend of grandeur and simplicity. The monumental portico, with its 16 massive Corinthian columns, commands attention and creates a sense of awe. Each column, made of Egyptian granite, is topped with intricately carved capitals that showcase the skill of ancient artisans [1]. The façade, with its large stone blocks, features a triangular pediment adorned with a simple yet elegant inscription that honours the building's purpose and its dedication to the gods. The entrance is framed by a wide flight of steps, inviting you to ascend and experience the majesty within. Surrounding the Pantheon, you observe the harmonious integration of the structure with its urban environment. The building's circular form contrasts beautifully with the rectangular streets of Rome, drawing your eye upward. The dome, a masterpiece of engineering, rises dramatically from the rotunda, showcasing its impressive height and smooth curvature. At the apex of the dome, the oculus serves as the only source of natural light for the interior, creating a dynamic interplay of shadows and illumination that shifts throughout the day. The exterior is finished with a combination of brick and concrete, demonstrating the innovative construction techniques of the Roman architects [1].

Figure 1: Photo of Pantheon and courtyard in 21st century [3]

The Pantheon has been an unmoving figure in Rome, since being built by Marcus Agrippa (during the reign of Augustus, 16 January 27 BC – 19 August AD 14), to both be a religious building, as well as a monument of the Roman Empire. The architectural innovation as well as the engineering of the building has made it a truly unique and memorable architectural structure, the meticulously crafted domed roof standing as an example of a near-perfect spherical dome to this day in the 21st century. The size of the Pantheon is striking, standing as the record for the largest dome built till modern times, standing at 142 feet (43 meters) in diameter and rising to a height of 71 feet (22 meters) above its base.

While the original structure has been damaged and changed many times since its original building, its name and location in the Campus Martius neighbourhood have remained constant. The Pantheon was completely rebuilt by Emperor Hadrian (11 August 117 – 10 July 138), constructed between July of 118 and sometime between 125 and 128 AD [4]. It was named "Pantheon" in honour of the Pantheon of Roman gods, as it was designed to worship all the deities in polytheistic Rome [1]. The polytheistic deities were the multiple gods that existed in ancient Roman culture, with many of these deities being carried from polytheistic Greece, each deity having a specific domain of rule. Jupiter the god of sky and thunder, and king of gods, is one of the most prominent ones. These deities range in prominence and fame throughout Rome.

After more than 600 years as a temple dedicated to the Roman gods, the Pantheon was converted into a church in 609 AD [1]. It has largely retained its original structure since that conversion, resembling its present form. The current form of the Pantheon is memorable in our time, as well as in ancient times. Two factors contribute to the success of the Pantheon, the excellent quality of the mortar used in the concrete and the careful selection and grading of the aggregate material, which ranges from heavy basalt in the foundations of the building and the lower part of the walls, through brick and tufa (a stone formed from volcanic dust), to the lightest of pumice toward the center of the vault. In addition, the uppermost third of the drum of the walls, seen from the outside, coincides with the lower part of the dome, seen from the inside, and helps contain the thrust with internal brick arches [2].

While its overall frame has remained unchanged, the Pantheon has experienced numerous modifications over time. Its surroundings have evolved, and various parts have been added or removed, along with decorative changes that reflect the eras and people it has coexisted with. These alterations contribute to changes in the Pantheon’s overall identity, the identity that is heavily connected to the overall cultural identity of Rome, even as some features fade into obscurity with time.

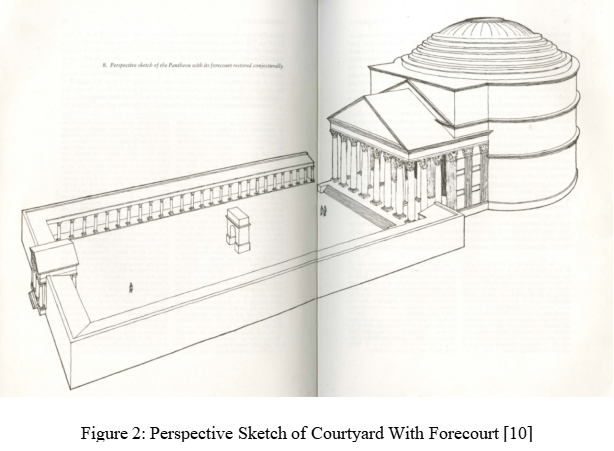

Some changes have occurred abruptly, introduced and removed within a few decades, while other elements have persisted for many years before being taken away. For example, in Roman Antiquity, a forecourt that had been in front of the Pantheon for quite some time was removed when it was converted into a church [1].

Figure 2: Perspective sketch of courtyard with forecourt [1]

An illustration in The Pantheon by William L. MacDonald depicts a sketch of the old complex with the forecourt intact (See Figure 2). The forecourt was long and rectangular, with its width slightly wider than that of the Pantheon itself. An entrance into the forecourt was located in the wall opposite the front, while an arch stood in the center, parallel to it. The walls of the forecourt slanted inward, supported by columns, and the front porch acted as the fourth wall, enclosing the court. This porch was supported by columns, forming a portico with a triangular gable above it, and was elevated by a set of stairs leading from the forecourt to the flat plane of the porch. The porch was attached to a rectangular structure, with the columns of the portico continuing, embedded in the Pantheon until the dome began. This forecourt had remained with the Pantheon throughout most of the Roman Empire's existence, and its removal, along with many adjacent buildings, signified a period of intense change after a significant length of time.

In modern times, modifications have been made continuously. One prominent example is the transformation of the Pantheon at the turn of the 20th Century, a project initiated by the Italian government in the 1890s, which marked a pivotal moment in the monument's history, significantly impacting its relationship with the surrounding urban landscape. Prior to this initiative, the Pantheon was somewhat enclosed by nearby buildings, which obscured its grand façade and limited public access. The government recognized the need to enhance the visibility of this iconic structure, a symbol of Rome's rich history. To achieve this, several adjacent buildings were demolished, clearing the area around the Pantheon and creating a more spacious piazza [4]. The redesign of the entrance played a crucial role in this transformation. A new, more prominent entrance was established, which not only improved access but also created a sense of grandeur that matched the scale of the Pantheon itself. The open space allowed visitors to appreciate the architectural beauty of the Pantheon from a distance, creating a more dramatic approach. Alongside the structural modifications, the Pantheon underwent updates that incorporated modern amenities. This included enhanced lighting systems that illuminated the interior and exterior, making the monument accessible for evening visits and enhancing its visual impact at night. Additionally, improvements in visitor facilities, such as informational displays and guided tours, were introduced to cater to the growing number of tourists [4].

This redevelopment was not merely about aesthetics; it also reflected a broader cultural movement in Italy during this period, where there was a strong emphasis on preserving national heritage while embracing modernization. The Pantheon, as a symbol of ancient Rome, became central to this narrative, representing the continuity of Roman identity through the ages. The changes led to an increase in tourism, as the Pantheon became more of a focal point for visitors exploring Rome's rich history. The newly created piazza became a vibrant public space, facilitating social interactions and community events, while also serving as a venue for religious ceremonies and gatherings. By balancing preservation with modernization, these modifications ensured that the Pantheon remained a vital part of the city's cultural and historical landscape, inviting both locals and tourists to engage with its storied past in a contemporary context. This adaptability is a testament to the Pantheon’s enduring legacy as one of the most important architectural feats of ancient Rome. The modifications made to the Pantheon, particularly in the early 20th century, resonate with its conversion from a Roman temple to a Christian church in several key ways. By removing surrounding buildings and creating a more open piazza, the Pantheon became more accessible, enhancing its function as a place of worship. The redesigned entrance facilitated the flow of people for liturgical activities, while modern lighting and visitor facilities catered to contemporary needs, blending its historical significance with active church use.

One factor that impacted changes in the Pantheon quite greatly was the idea of patronage, where a wealthy group or individual with power was able to fund the pantheon in return for a certain repayment. In most cases, the Pantheon being the Pantheon, that repayment came in the form of public acknowledgement of the patronage through the Pantheon itself. In the late 1500s, one individual who greatly impacted the pantheon was Pope Urban VIII (1521-1590), who made numerous changes to its structure under the guise of repairs. He replaced the bronze trusses with a new system of timber rafters, collars, purlins, struts, and braces, implemented by Francesco Borromini (1599-1667) [4]. To enact these changes, some parts had to be removed, including the 13th-century bell towers that had previously been part of the structure. In compensation, he added twin towers and repaired the missing column on the northeast corner of the portico. A Barberini bee was carved onto the capital of this column, forever marking the Pantheon with his family symbol for all to see [4]. (See figure 3) This transformation not only demonstrated Pope Urban VIII’s power over the building but also highlighted its importance as a site of cultural and social value.

Figure 3: Photo of Barberini bee carved into portico column [5]

By inscribing a family crest onto the Pantheon, it indicated that the structure was deemed valuable enough to warrant control and influence from a powerful family like the Barberini [1]. This marked a shift in the Pantheon’s role within the city, evolving from a temple dedicated to the gods to a symbol of political significance. The space of the area indicates the intention of the space, originally being designed to be a temple, the structure conveys a sense of ritual worship, with an open area and a majestic interior, resembling the awe-inspiring nature of gods, leading it to work well as a church, also an area of worship. It pushes on into modern times as the space and structure continue to convey majesty and awe, leading it to have a sense of importance and magnitude, as more people come from around the world just to see it.

These changes also reflect a broader cultural narrative of preserving national heritage while embracing modernization. The Pantheon symbolizes Rome’s enduring religious and cultural identity, fostering community engagement through public gatherings and events. Additionally, structural reinforcements aimed at preserving the building's integrity echo the initial conversion efforts in the 7th century. Overall, these modifications reinforce the Pantheon’s role as a living monument honoring its past while adapting to modern demands, highlighting its unique ability to connect ancient and contemporary worlds.

3. Interpretations and public response

As time has passed, the attitudes toward the Pantheon have shifted significantly, reflecting a transition from the perspective of the powerful to that of the ordinary citizen. Initially, the building served as a sacred site for the elite patrons who commissioned it, seen as an untouchable and holy space dedicated to the gods. However, over the centuries, people have increasingly modified the Pantheon to cater to public pleasure and contemporary whims. This stark contrast to its original sacred nature highlights how the building evolved into a multifunctional space, reflecting the desires of the broader community rather than just the elite.

In recent years, there has been a growing interest in conservation and preservation, prompting a return to maintaining the Pantheon in its original form [4]., This shift signifies a new respect for its historical and architectural integrity, treating it as a cultural artifact rather than merely a space for public enjoyment. Thus, the Pantheon is slowly becoming less of a canvas for alteration and more of a monument to be cherished in its untouched state, albeit for different reasons than in its early days.

Figure 4: Digital image of tomb of Jean Moulin in Panthéon [6]

As the centuries progressed, the Pantheon continued to evolve, reflecting deeper cultural shifts and the changing perceptions of Roman and later European society. The structure, originally conceived as an emblem of divine power, had come to symbolize much more: from a temple of pagan gods to a center for Christian worship, and eventually to a celebrated monument of historical and architectural significance.

During the Middle Ages, the Pantheon’s role as a Christian church allowed it to remain relevant, even as many other ancient structures in Rome fell into ruin. As Christianity became the dominant religion in the Roman world, the Pantheon’s survival owed much to its repurposing [4]. This transition marked a crucial moment in the history of the building, but also in the history of Rome. The continuity of the structure ensured that, despite the changing social, political, and religious context, the Pantheon retained its physical presence and symbolic importance in the cityscape.

The 16th-century Renaissance brought a renewed reverence for classical antiquity, which included a reappraisal of buildings like the Pantheon. Artists, architects, and scholars admired the Pantheon not only for its technical brilliance but also as a symbol of a golden age of knowledge and creativity. This revival of classical ideals was not merely nostalgic but a deliberate attempt to align contemporary culture with the high achievements of the past. As a result, Renaissance-era interventions did not simply seek to preserve the building; they sought to enhance it and integrate it into the aesthetic and spiritual fabric of the time.

In the 19th century, the Pantheon became a focus of national pride, particularly as the unification of Italy brought a new sense of collective identity. The building, now a secular monument to Rome’s imperial past, was reimagined as a symbol of the enduring greatness of Roman civilization. This period saw the beginning of its status as a tomb for famous Italians, starting with the painter Raphael in 1520 and followed by kings and other prominent figures [4]. The Pantheon’s transformation into a mausoleum further solidified its role as an emblem of Italy’s historical continuity, bridging ancient Rome and the modern Italian state.

By the 20th century, the Pantheon had become a major tourist destination and a symbol of global cultural heritage. As Italy and much of the world entered an era of increasing mobility, the Pantheon’s influence grew beyond its local context. Its architectural form—particularly its dome, one of the largest unreinforced concrete domes in the world—became a symbol of human ingenuity, inspiring modern architects and engineers [4]. The Pantheon, thus, was no longer just a relic of Rome's imperial past; it had become a universal icon of architectural innovation and a reminder of the enduring power of human creativity.

Figure 5: Black and white photo of the Pantheon in the Piazza della Rotonda with two towers built upon it [7]

Through these various phases, the Pantheon’s treatment and significance have reflected broader cultural shifts. From its beginnings as a tool of imperial propaganda to its adaptation as a site of Christian worship, to its eventual reemergence as a symbol of both national pride and global cultural heritage, the Pantheon embodies the dynamic interplay between architecture and society. Its continued transformation underscores how monuments are not static relics but living symbols that evolve in response to the changing values, beliefs, and needs of the societies that preserve and reinterpret them. The Pantheon’s story reveals how buildings, through adaptation and preservation, can serve as lasting witnesses to history, acting as both a mirror of cultural change and a bridge to the past.

4. The Pantheon in relation to the public

As more and more, people have been willing to change and modify the Pantheon to public pleasure, and their whims, a stark contrast to the past sacred nature of the building, as untouchable and holy. However, with a recent turn and interest in conservation and preservation, the building is slowly returning to being untouched, this time for a different reason.

Originally the Pantheon was designed with the idea of deities and gods in mind, with that symbolism shining through. The rising structure symbolized a dedication and reach toward the gods in the sky, however as times changed social norms changed too. A turning point, in the history of the Pantheon is when the social standard changed from adding symbols and ideals onto the Pantheon to preserving and fixing what is present. From gods to symbols leading to the absence of symbols, social structure changes and changes how people treat the Pantheon and with modern times came a rise in the idea of preservation. In the 18th and 19th centuries, significant renovations were undertaken, including restoring the portico and the dome [4]. More recently, ongoing preservation efforts aim to protect the structure from pollution and environmental degradation, ensuring it remains a vital part of Rome's architectural heritage.

Two towers added in the 19th century serve as a prominent example of the change in the role of the Pantheon [8]. (See Figure 5) Illustrations often highlight the structure in an urban environment of a public courtyard, depicting it without the forecourt and with buildings attached.

The Pantheon is portrayed at the side of a clearing, surrounded by buildings, with a fountain in the middle. It is slightly elevated from ground level, with a couple of steps leading to the plane of the porch. The porch itself is surrounded by columns and features a triangular roof, which is connected to the rectangular volume of the Pantheon. This rectangular structure leads to the cylindrical form and dome behind it, rising slightly higher than the triangular roof of the porch. The rectangular structure has two towers built atop it, each occupying one side of the rectangle. These identical round towers extend along the length of the rectangular structure, with a width of approximately one-third of its overall width. The towers rise just above the height of the dome behind them and feature arches cut into the walls on all four sides. The cupola on top of the towers is pyramid-shaped, with outward-curving edges and spires at the apex. Within the towers, bells signify the structure's status as a church, as bell towers are typically found in churches. This transformation firmly established the Pantheon as a Christian structure, distinguishing it from its ambiguous Roman origins and signalling its new purpose.

In modern times, the Pantheon continues to serve as an active place of worship, hosting religious services and ceremonies. These events draw both locals and tourists, fostering a sense of community and continuity in a historical setting. The Pantheon began shaping and influencing traditions and actions beyond its local scope, such as being a part of a key destination in the Grand Tour, a coming-of-age tour of Europe that young upper-class European men partook in [9]. The integration of contemporary changes within such an ancient structure highlights the ongoing relevance of the Pantheon in today’s society. The Pantheon has adapted to the demands of modern tourism. Measures have been implemented to manage the flow of visitors, including timed entry tickets and guided tours, enhancing the visitor experience while preserving the sanctity of the site. These changes reflect a balance between cultural heritage and the commercial aspects of tourism, making the Pantheon accessible to millions each year [3]. The Pantheon in Rome is perceived as a vital repository of cultural identity and history. The site reflects the artistic, architectural, and historical achievements of civilizations, serving as icons that connect present and future generations to their past. The Pantheon, with its remarkable dome and ancient design, stands as a testament to Roman engineering and cultural significance.

Figure 6: Painting of young European nobles touring the countryside on the Grand Tour [10]

This significance is also carried into the modern days, with new-age technological engineering also advancing the experience of the Pantheon, and adding to the Pantheon itself. Recent technological advancements such as augmented reality (AR) applications and digital guides offer visitors interactive ways to engage with the history and architecture of the site. One such example is the company Aeon Reality which offers an immersive history lesson on the Pantheon through their augmented reality solutions on their platform EON-XR [11]. These tools enhance educational opportunities and provide deeper insights into the Pantheon’s significance. The Pantheon, while an ancient monument, continues to evolve in the modern era. Its transformation from a temple to a church, ongoing restoration efforts, cultural relevance, and adaptation to tourism and technology reflect the dynamic relationship between history and contemporary society. As a result, the Pantheon remains not only a symbol of ancient Rome but also a living space that bridges the past with the present. It is currently considered a part of the UNESCO World Heritage Site of the Historic Center of Rome, seen as a major monument of antiquity included in the site along with areas such as the Colosseum and the Roman Forum. The protection of heritage sites is crucial for preserving these irreplaceable resources [12]. Organizations like UNESCO (the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization) play a pivotal role in this effort. UNESCO designates World Heritage Sites based on their outstanding universal value, which helps raise awareness and mobilize resources for their conservation. This designation not only recognizes the cultural significance of sites like the Pantheon but also promotes global cooperation in their preservation.

Many online platforms offer virtual tours and 3D reconstructions of the Pantheon, allowing users to explore the interior and exterior at their own pace. These projects often provide detailed information about architectural features, enhancing the overall experience. One of the primary merits of virtual tours is their accessibility. They make the Pantheon reachable to a global audience, especially for those unable to visit in person. Additionally, these tours frequently include historical context and architectural insights, enriching users' understanding of the site. AR applications have also been developed to enhance the visitor experience at the Pantheon. These apps allow users to point their devices at the monument and see overlays of historical information, reconstructions, or artistic interpretations. The engagement factor here is significant; AR can make learning interactive and appealing, drawing in younger audiences and tech-savvy users. Furthermore, these applications enable users to visualize how the Pantheon looked in different historical periods, providing a richer understanding of its evolution.

Community projects and crowdsourced content are other noteworthy aspects of Pantheon-related initiatives. Some platforms encourage users to upload their photos, stories, and interpretations of the monument, fostering a sense of shared ownership and highlighting diverse perspectives. This inclusivity allows for a wide range of voices to be heard, reflecting various cultural and personal connections to the Pantheon. The content is constantly updated, offering fresh insights and narratives [11]. Numerous educational websites and blogs also focus on the Pantheon, providing articles, videos, and infographics about its history, architecture, and cultural significance. These platforms often feature scholarly articles and expert interviews, offering well-researched insights that deepen users' understanding. The variety of formats, including text, video, and images, caters to diverse learning preferences.

Overall, the public appreciation of historical buildings has generally increased in modern times, driven by several key factors that reflect a growing awareness of cultural heritage, architectural significance, and community identity. As educational initiatives and public awareness campaigns about cultural heritage have expanded, more people recognize the importance of preserving these structures. Schools, museums, and cultural organizations increasingly emphasize the value of history and architecture, fostering a deeper appreciation for historical sites. Technological innovations, particularly in digital media and communication, have also made historical buildings more accessible to a global audience. Virtual tours, augmented reality applications, and online resources allow people to explore and learn about these structures from anywhere in the world, broadening public engagement and interest. The rise of cultural tourism further contributes to this appreciation, as many cities promote their historical sites as attractions, drawing visitors eager to experience cultural heritage. This influx of tourism often leads to increased funding for preservation efforts and community initiatives aimed at maintaining these building

5. Modern impact

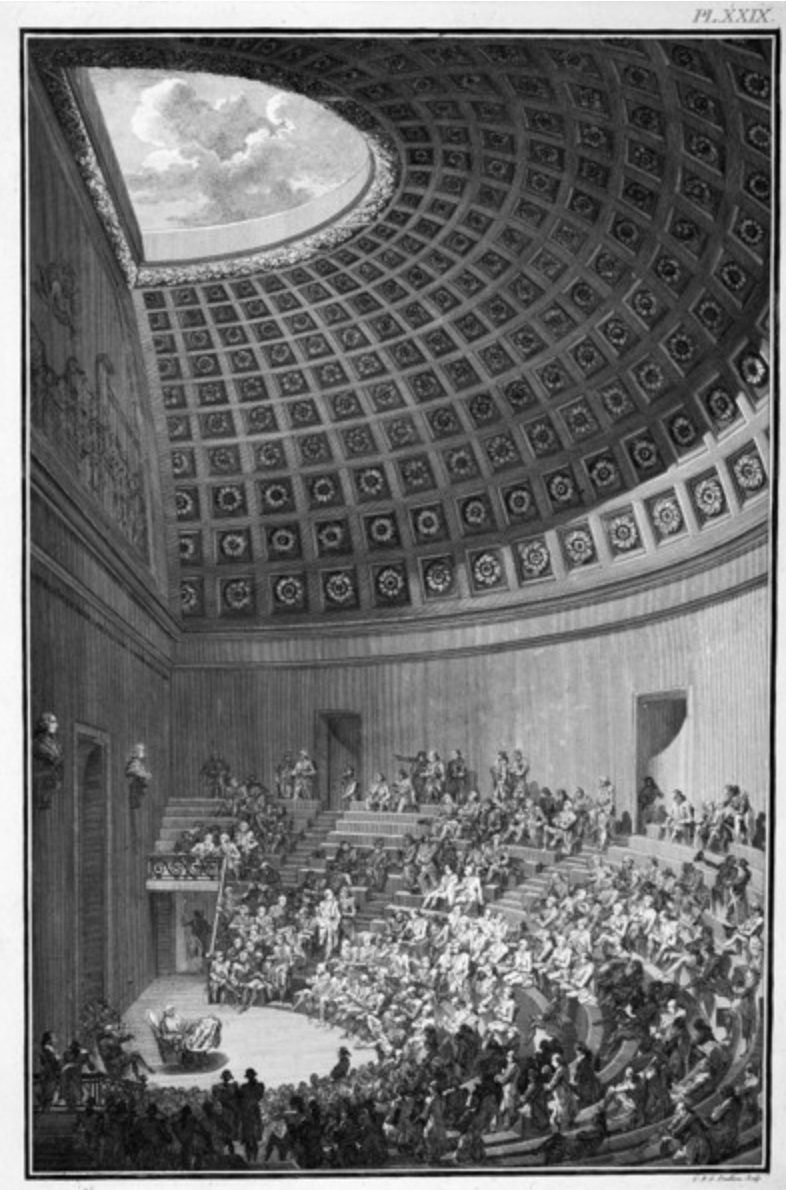

The Pantheon's impact on the modern world has only grown, serving as an important architectural inspiration and symbol well beyond the city of Rome. It carries the legacy of the past, attracting visitors from all over the globe. Its perfect dome, surrounded by exterior pillars and rising from the second interior ring cornice of the rotunda, has inspired countless contemporary buildings across various usages and origins. Examples include the medical operation amphitheatres of the School of Surgery in Paris, the Guggenheim Museum in New York, and the Altes Museum in Berlin [13] Although all these locations were built in wildly different times and places, they all share the common traits of the Dome of the Pantheon. All of these buildings have drawn influence from the Pantheon as an architectural motif and replicated the most iconic part, the dome upon their buildings.

Figure 7: Drawing of the anatomy theatre in the Ecole de Chirurgie [14]

The School of Surgery in Paris is an effective example of such an occurrence, taking motifs and inspiration from the Pantheon while adapting the structure to the needs of the building itself. A neoclassical print from 1780 by Jacques Gondon, a French architect and designer, shows the School of Surgery (Ecole de Chirurgie) in Paris, specifically the anatomy theatre also designed by Jacques Gondon. (See figure 7) The anatomy amphitheatre was used to show students practical applications of medicine, such as surgery or anatomical body parts. The image shows a semicircular room with a flat wall on the left and a rounded wall on the right, to form a semicircular room. The room has rows of ascending benches that follow the curve of the curved wall, forming a semi-circle around the focal point of the opening at the bottom of the benches, where the presenter would demonstrate surgery to the students. The roof of the room has the shape of a half dome with an oculus on the top of the dome, giving the room the sensation of a circular domed room cut in half with a flat wall. The dome is coffered, with rosettes in each square coffer arranged linearly. It’s quite visible that the School of Surgery took inspiration from the Pantheon through the dome. The roof of the amphitheatre extends into a perfect semicircular dome, both keeping similar coffers and the oculus of the Pantheon itself. However, it adapted the design to the needs of the school, cutting the design in half not only to attach it to the rest of the school but also to adapt the oculus to be larger to illuminate the room as visibility is quite important in an amphitheatre.

This widespread influence extended beyond Rome and into global notoriety, serves as a signifier of change The Pantheon serves as a symbol of Roman history and culture, with its dome playing a central role in that identity. As time progresses, the Pantheon’s role and vision in society continue to change. These historical shifts reflect the evolving context around it, contributing to its current identity. The Pantheon has transitioned from a religious meeting place to a site of political importance and now stands as a renowned tourist attraction. Despite the many changes it has undergone, at its core it remains acknowledged as an important and marvellous feat of Roman architecture and engineering, the idea staying stable even as the Pantheon's role is changed. It physically remains and continues to hold significance in the minds of people, with hopes of enduring for many more years to come.

The Hagia Sophia embodies both Christian and Islamic heritage, making it a crucial site for understanding the historical and cultural interactions between these two major world religions. Its innovative design, particularly the massive dome, has influenced countless structures around the world, including mosques and churches [15]. Similarly, originally built as a temple for Roman gods, the Pantheon was later converted into a church in the 7th century [1]. Like the Hagia Sophia, it reflects the shift from paganism to Christianity and has maintained its architectural integrity through the centuries. Both structures serve as examples of how religious sites can adapt to changing cultural contexts while retaining their historical significance. The Pantheon exists as a religious and architectural historical monument in Italy, much like the Hagia Sophia does in Turkey [15]. Its preservation as a cultural heritage site showcases the complexities of cultural coexistence and memory in a post-colonial context. This ongoing project represents a blend of religious devotion and architectural innovation, drawing comparisons to the Hagia Sophia's historical significance and ongoing relevance. The Hagia Sophia's status has been deeply intertwined with political agendas throughout its history. The conversion of the Hagia Sophia into a mosque was a powerful political statement by the Ottomans, symbolizing their conquest and the establishment of Istanbul as a center of Islamic culture [15]. In the early 20th century, the secularization of the Hagia Sophia into a museum reflected the nationalist and secularist reforms of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, aimed at modernizing Turkey and distancing it from its Ottoman past [15]. The 2020 reconversion of the Hagia Sophia into a mosque by President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has been seen as part of a broader political strategy to assert Islamic identity and heritage in Turkey [16]. This move has garnered both domestic support and international criticism, highlighting ongoing tensions between secularism and religious identity in contemporary Turkish politics. The Hagia Sophia serves as a powerful symbol of the interplay between religion, culture, and politics throughout history. Its transformations reflect broader global contexts and the complex narratives that shape religious sites today. By examining the Hagia Sophia through a comparative lens with structures like the Pantheon and understanding its political significance, we gain deeper insights into the challenges and opportunities of cultural heritage in a rapidly changing world.

6. Conclusion

The Pantheon in Rome serves as a profound testament to the enduring interplay between architecture, religion, and cultural identity. The structure has navigated significant transformations over the centuries, reflecting the shifting tides of societal values and political landscapes. From its origins as a temple dedicated to the divine to its current roles as symbols of heritage and resilience, these monuments embody the complexities of human history and the narratives that shape our understanding of the past.

As we consider the Pantheon’s journey through time—from a revered temple to a church and now a vital tourist attraction—we recognize the importance of preserving such sites not only for their architectural brilliance but also for their capacity to foster connections between cultures and generations. The ongoing efforts to maintain the Pantheon and similar heritage sites underscore the necessity of balancing modernization with the integrity of historical structures, ensuring that they continue to inspire awe and reflection. The adaption to the use of technology significantly enhances accessibility to the Pantheon, allowing for virtual tours and augmented reality experiences that enable people worldwide to appreciate its grandeur without needing to visit in person. Online resources provide detailed historical context, while streamlined ticketing and navigation apps make visiting easier for tourists. As technology continues to evolve, these projects can further enrich the understanding and experience of the Pantheon, bridging the gap between the ancient and modern worlds. However, the accuracy and reliability of content can vary, so users should approach these resources with a critical eye.

The preservation and appreciation of historical buildings carry significant implications for cultural identity and societal values. The evolution of monuments like the Pantheon, from temples to churches and now vital tourist attractions, highlights their deep cultural and historical significance. These sites serve not only as architectural marvels but also as essential connections between diverse cultures and generations. As historical structures adapt to contemporary needs, it becomes crucial to balance modernization with the integrity of their original design, ensuring they continue to inspire awe and reflection.

Moreover, historical monuments remind us of our shared heritage, emphasizing the importance of cultural legacy in our increasingly globalized world. They invite exploration of our diverse paths and instill a sense of identity and continuity, reinforcing the notion that understanding our past is vital for navigating the future. The responsibility to protect and honour these irreplaceable symbols falls on current generations, fostering a deeper understanding of cultural heritage and encouraging respect for the narratives encapsulated in these structures. Ultimately, the preservation of historical buildings is a vital endeavour that shapes cultural identity, promotes understanding, and connects us to our shared history in a rapidly changing world.

In a world increasingly defined by rapid change and globalization, the significance of these monuments remains steadfast. They remind us of our shared history and the diverse paths we have traversed. The Pantheon and the Hagia Sophia stand as living legacies, inviting us to explore the rich tapestry of our cultural heritage while challenging us to protect and honour these irreplaceable symbols for future generations. Through their preservation, we cultivate a deeper understanding of who we are and where we come from, fostering a sense of continuity in an ever-evolving word.

References

[1]. MacDonald, William Lloyd. The architecture of the Roman Empire. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1988.

[2]. Kostof, Spiro, and Greg Castillo. A history of architecture: Settings and rituals. New York: Oxford University Press, 2023.

[3]. Campbell, Jeffrey S. Pantheon. Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, November 6, 2009. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Pantheon-building-Rome-Italy#/media/1/441553/129566.

[4]. Marder, Tod A., and Mark Wilson Jones. The pantheon: From antiquity to the present. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019.

[5]. Leatherbarrow, David. Building time: Architecture, event, and experience. London: Bloomsbury Visual Arts, 2021.

[6]. Prieur, Benoît. Tomb of Jean Moulin in Panthéon. Wikimedia Commons. Wikipedia, August 8, 2023. https://commons.m.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Tomb_of_Jean_Moulin_in_Panth%C3%A9on,_August_2023.JPG.

[7]. The Pantheon, Rome, Italy. United States Library of Congress’s Prints and Photographs Division. Library of Congress, 1870. https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/93512726/.

[8]. Meeks, Carroll L. “Pantheon Paradigm.” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 19, no. 4 (December 1, 1960): 135–44. https://doi.org/10.2307/988113.

[9]. Gelléri, Gábor. Lessons of travel in eighteenth-century France: From grand tour to school trips. Woodbridge: The Boydell Press published in association with BSECS, 2020.

[10]. Carl Spitzweg, English Tourists in Campagna, Blindex (Blindex, 1845), https://www.bildindex.de/document/obj02531950?part=0.

[11]. Kjallstrom, Brita. “Immersive History - Ar Roman Pantheon.” EON Reality - AI Assisted XR-based knowledge transfer for education and industry, December 9, 2024. https://eonreality.com/immersive-history/.

[12]. Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. “Historic Centre of Rome, the Properties of the Holy See in That City Enjoying Extraterritorial Rights and San Paolo Fuori Le Mura.” UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Accessed February 8, 2025. https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/91. Carl Spitzweg, English Tourists in Campagna, Blindex (Blindex, 1845), https://www.bildindex.de/document/obj02531950?part=0.

[13]. GONDOIN, Jacques. Description des écoles de chirurgie. Riba. RIBA Collections, 1737. https://www.ribapix.com/school-of-surgery-ecole-de-chirurgie-paris-the-anatomy-theatre_riba10071.

[14]. GONDOIN, Jacques. Description des écoles de chirurgie. Riba. RIBA Collections, 1737. https://www.ribapix.com/school-of-surgery-ecole-de-chirurgie-paris-the-anatomy-theatre_riba10071.

[15]. Lozanovska, Mirjana. “Hagia Sofia (532–537AD): A Study of Centrality, Interiority and Transcendence in Architecture.” The Journal of Architecture 15, no. 4 (August 16, 2010): 425–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/13602365.2010.507521.

[16]. “Hagia Sophia: Turkey Turns Iconic Istanbul Museum into Mosque.” BBC News, July 10, 2020. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-53366307.

Cite this article

Yuan,E.Y. (2025). The Cultural Impact of the Pantheon Post Classical Era. Communications in Humanities Research,69,61-73.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Literature, Language, and Culture Development

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. MacDonald, William Lloyd. The architecture of the Roman Empire. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1988.

[2]. Kostof, Spiro, and Greg Castillo. A history of architecture: Settings and rituals. New York: Oxford University Press, 2023.

[3]. Campbell, Jeffrey S. Pantheon. Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, November 6, 2009. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Pantheon-building-Rome-Italy#/media/1/441553/129566.

[4]. Marder, Tod A., and Mark Wilson Jones. The pantheon: From antiquity to the present. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019.

[5]. Leatherbarrow, David. Building time: Architecture, event, and experience. London: Bloomsbury Visual Arts, 2021.

[6]. Prieur, Benoît. Tomb of Jean Moulin in Panthéon. Wikimedia Commons. Wikipedia, August 8, 2023. https://commons.m.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Tomb_of_Jean_Moulin_in_Panth%C3%A9on,_August_2023.JPG.

[7]. The Pantheon, Rome, Italy. United States Library of Congress’s Prints and Photographs Division. Library of Congress, 1870. https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/93512726/.

[8]. Meeks, Carroll L. “Pantheon Paradigm.” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 19, no. 4 (December 1, 1960): 135–44. https://doi.org/10.2307/988113.

[9]. Gelléri, Gábor. Lessons of travel in eighteenth-century France: From grand tour to school trips. Woodbridge: The Boydell Press published in association with BSECS, 2020.

[10]. Carl Spitzweg, English Tourists in Campagna, Blindex (Blindex, 1845), https://www.bildindex.de/document/obj02531950?part=0.

[11]. Kjallstrom, Brita. “Immersive History - Ar Roman Pantheon.” EON Reality - AI Assisted XR-based knowledge transfer for education and industry, December 9, 2024. https://eonreality.com/immersive-history/.

[12]. Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. “Historic Centre of Rome, the Properties of the Holy See in That City Enjoying Extraterritorial Rights and San Paolo Fuori Le Mura.” UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Accessed February 8, 2025. https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/91. Carl Spitzweg, English Tourists in Campagna, Blindex (Blindex, 1845), https://www.bildindex.de/document/obj02531950?part=0.

[13]. GONDOIN, Jacques. Description des écoles de chirurgie. Riba. RIBA Collections, 1737. https://www.ribapix.com/school-of-surgery-ecole-de-chirurgie-paris-the-anatomy-theatre_riba10071.

[14]. GONDOIN, Jacques. Description des écoles de chirurgie. Riba. RIBA Collections, 1737. https://www.ribapix.com/school-of-surgery-ecole-de-chirurgie-paris-the-anatomy-theatre_riba10071.

[15]. Lozanovska, Mirjana. “Hagia Sofia (532–537AD): A Study of Centrality, Interiority and Transcendence in Architecture.” The Journal of Architecture 15, no. 4 (August 16, 2010): 425–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/13602365.2010.507521.

[16]. “Hagia Sophia: Turkey Turns Iconic Istanbul Museum into Mosque.” BBC News, July 10, 2020. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-53366307.