1. Introduction

Kucha (Qiuci), described by Han Shu as one of the “Thirty-six countries in the Western Regions”, [1] is an important oasis kingdom on the northern Silk Road path across the Tarim basin in modern-day Xinjiang. It is situated in the central region of Eurasia, linking Central and Southern Asia with inner China. Because of its position, Kucha has long been the center of economic and cultural changes in Eurasia.

Buddhism, being founded in Southern Asia, was spread into the Indus Valley and along the Silk Road by monks and merchants in later centuries. It is found that in 91 CE, if not earlier, the royal family of Kucha had already converted to Buddhism. [2]

The Kizil caves, situated 65 km west of Kucha, are one of the most famous architectures indicating the development of Buddhism in ancient Kucha state. [3] There are overall 236 caves in Kizil, constructed between the end of the 3rd century CE and the 8th century CE. [4] Observing a connection between the development of commercial trade and Buddhism in the 6th and 7th centuries CE through analysis of the mural paintings in Kizil caves, this article works to identify the interdependent relationship between Buddhism and commerce. Kizil caves No.17 and No.205 will be used as evidence in this article. Caves No.205 will be used to support the hypothesis that commerce promotes Buddhism because of the accumulation of wealth, while the mural paintings in caves No.17 will be analyzed to prove that Buddhism helped to dignify the practice of commerce.

2. Commerce promotes Buddhism through the contribution of wealth

A parallel timeline between the Silk Road trade’s peak and the Kizil caves’ construction is found through historical records and journals, therefore supporting the argument of commerce promoting Buddhism. The commercial activities on the northern and middle paths of the Silk Road became increasingly prosperous and frequent during the Sui and Tang dynasties (6th century CE to 9th century CE), bringing great wealth and exchanges of goods to Kucha, the centric kingdom. Figure 1 is from a manuscript discovered in Kucha, recording the flow of population between inner China and the ancient Kucha. [5] Each caravan contains about fifty merchants entering the Kucha state and different caravans pass by frequently. This material indicates the flourishing trade between China and Kucha during the Tang dynasty.

Figure 1: Kucha manuscript [5]

Large amounts of luxurious goods and wealth are therefore deduced to be brought into the Kucha kingdom through trade. Paralleled with flourishing commerce, the Kizil caves, as the representation of Buddhist culture in Kucha, were constructed on a large scale during the period between 550 CE and 650 CE, the Sui and Tang dynasties. [6] Therefore it is speculated that the wealth gained by Kucha through trade promoted the development of Buddhism. This section analyzes the images of patrons on the walls of Kizil caves No. 205 to support the speculation.

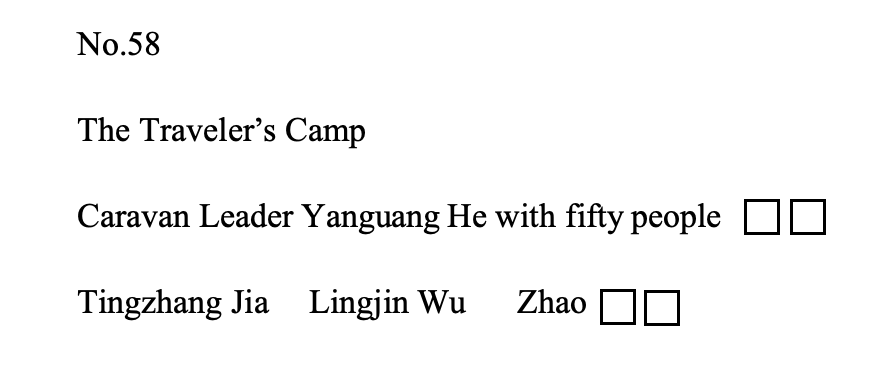

Cave No. 205 was built at the end of the 6th century CE. [7] It is a central pillar cave with images of its donor on the lower level of the northern wall. [8] The male and female figures in the middle of the image stand out because of the cartouche placed behind them, indicating noble positions. The identity of the female is recorded by the Brahmi inscription written on the wall -- “Kuci[maha](de)[vya]svaya(m)pra[bh](a)”, which means the Great Kucha Queen, Svayamprabhā. [9] This material indicates the royal identities of figures on the wall, with the male being King Tottika, the husband of Queen Svayamprabhā. [8] The king is dressed in a robe with black, blue, and green stripes of ornaments. The sleeves are tight and pinched, with yellow wristbands made of gold. Ornamental lines of white dots that might be diamonds or embroidery are decorated on the cloth around the king’s chest and the hem of the robe. The king is wearing a gold belt and holding an incense in his left hand. A string of round white spheres like pearls is also found around the king’s neck, but the right part is destroyed so it couldn’t be identified clearly. Queen Svayamprabhā’s image is also depicted exquisitely. She wears an elegant dress decorated with green, black, and blue stripes. The hem of her dress is full of fancy and beautiful embroidery which seems like butterflies and flowers. The queen’s lapel is also interspersed with little white dots. A long riband adorned with jewelry and precious stones intertwines around her neck. The extremely fancy and luxurious clothing with precious ornaments like gold, pearls, and several kinds of jewelry dressed by the royal patrons on the wall indicate the great wealth possessed by the Kucha state.

Figure 2: Kizil Cave 205 donor image, Asian Art Museum, Berlin [10]

It is argued that the wealth of Kucha is gained through commerce along the Silk Road. The similarity appearing between the clothing of Kucha royal patrons and Central Asia residents supports the existence of goods exchanges in Kucha. Presented in the mural painting, the king and the queen’s clothing outstands in its unique style --- robe with a triangular collar and patterns decorated on it, a belt around the waist, skinny pants, and pointed boots. This kind of dressing is quite different from the clothing style in inner China, however highly similar clothes are found in Central Asia.

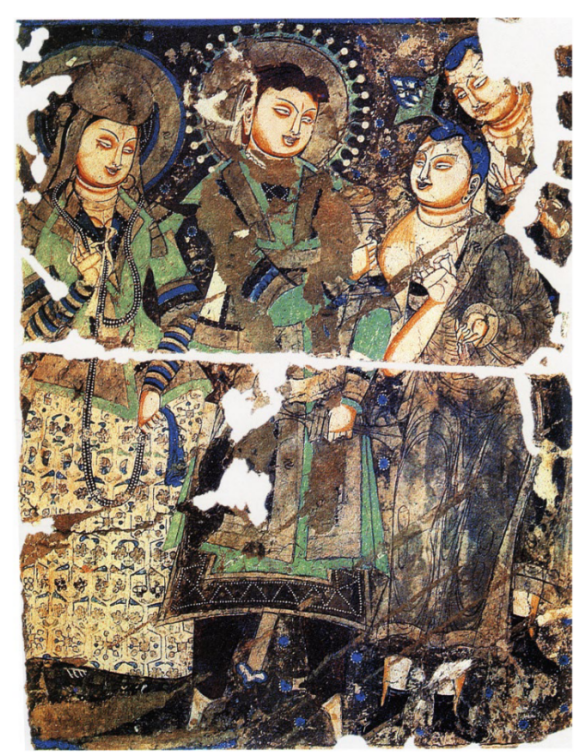

Figure 3: Kushan male figures, room No.16, northeastern corner of the Dilberjin Tepe, Blkh, Afghanistan [11]

Figure 3 is from the wall paintings in Dilberjin Tepe, an archaeological site for ancient city centers under the Kushan empire in modern-day Afghanistan. This painting can be traced back to around the 6th century, parallel with the construction of Kizil caves in time. [11] The same kind of robe, triangular collar, belt, skinny pants, and pointed boots are identified from the male figures in the picture, suggesting an exchange of goods and culture between the Kushan empire and Kucha. The Kushan Empire is situated in the Bactrian region in Central Asia, north of the Hindu Kush Mountain. Therefore, the commerce between Kushan and Kucha may have constituted part of the flourishing Silk Road trade between Central and Eastern Asia during the Sui and Tang dynasties.

By analyzing images of the Kizil cave donors and comparing them to paintings in Central Asia, it can be deduced that under the historical context of prosperous Silk Road trade during the 5th to 7th century CE, Kucha, as a centric state along the roads, gained a large amount of money and luxurious goods from the commerce, which enriched the royal family and enabled them to support Buddhism and construct the Kizil caves extensively. Therefore, the conclusion of commerce promoting Buddhism can be drawn.

3. The practice of Buddhism dignifies commerce

In addition to the promotion of commerce towards Buddhism, the spiritual activities and doctrines of Buddhism help to dignify commerce and merchants. Being an oasis kingdom watered by the glacier-melted water from the Tian Shan range, Kucha is always an agricultural society and merchant is overall a rare lifestyle adopted. As recorded by Xuanzang when he passed here, “The soil is suitable for rice and corn, also (a kind of rice called) keng-t'ao; produces grapes, pomegranates, and numerous species of plums, pears, peaches, and almonds, also grow here.” [12] However, the increasing practices of Buddhism in Kucha improved and emphasized the status of commerce through the stories in Buddhist doctrines that praise merchants. This is shown in the mural paintings in the Kizil caves.

Figure 4: The merchant Safur, cave No. 17, the Kizil caves, Kucha, Xinjiang province, China [13]

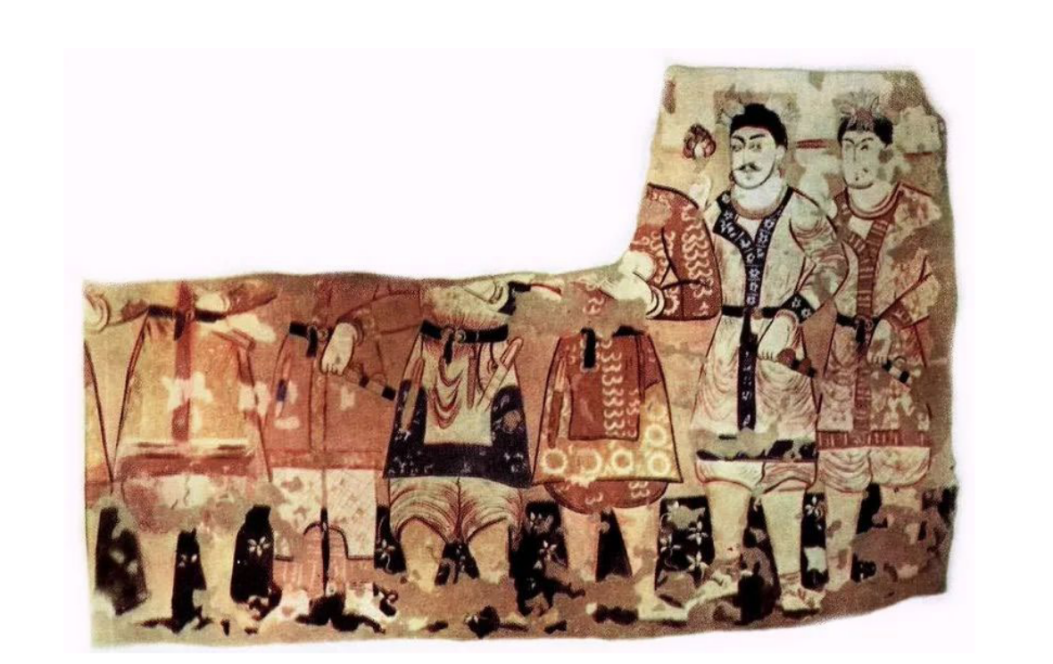

Figure 4 is a mural painting from cave No. 17, which tells the story of a merchant called Safur in the Xianyu Sutra, a classical Buddhist story collection. The story is that there is a caravan of five hundred merchants that lost its way in a forest. The sky is getting dark and the howl of beasts can be heard from a distance. Even worse, it is said there are bandits attacking passengers in this area, All the merchants are extremely scared and begin to cry for help, except one named Safur. He is kind-hearted and willing to help others. Out of other’s surprise, he takes out a roll of cloth, soaks it with grease, and wraps it on both of his arms. Then he lights up the cloth as a torch to lead a way in the front. Encouraged by his deed, the merchants finally walk out of the forest after three days of traveling. [14] By describing Safur as a noble and self-giving person who accords with the doctrines of Buddhism, merchants are dignified and praised by Buddhism, therefore increasing their status. The image of merchants in Figure 4 is depicted authentically, in the clothing of robe, skinny pants, and pointed boots, which points to the cultural and commercial interaction between merchants along the Silk Road.

The same Buddhist story of merchants is also found on the mural paintings in caves No. 8, No. 38, No. 58, No. 114, and No. 178. Other stories involving and praising merchants in Kizil caves are identified by the clothing and goods of the figures. This visual presence of Jataka Tales in Buddhist architecture helps to increase people’s embracement towards merchants. Therefore, the practice of Buddhism dignifies commerce.

Figure 5: The merchant of Safur, cave No. 38, the Kizil caves, Kucha, Xinjiang province, China [13]

4. Conclusion

In conclusion, this article argues for the interdependent relationship between Buddhism and commerce in Kucha history based on the Kizil caves. To support the argument, this article works on the analysis of mural paintings inside the Kizil caves, a primary source indicating Buddhism in ancient Kucha. Images of royal patrons found inside cave No. 205, painted during the Chinese Tang dynasty, indicate the extreme extravagantness and luxuriousness of Kucha elites, with jewelry ornaments and clothing obtained through cross-regional commerce. Patronized caves are built only after the 5th and 6th centuries, together with the flourishing of the Silk Road exchange and the inflow of wealth from trade, therefore demonstrating the promotion of commerce to the development of Buddhism. Analysis of the merchant story on mural painting discovered in caves No. 17 supports the argument that the construction of Kizil caves and other Buddhist spiritual architecture can dignify merchants and therefore their commercial practices, further promoting commerce in Kucha, an originally agricultural kingdom. This article contributes to a more comprehensive understanding of the development of Buddhism along the Silk Road in ancient times, suggesting an important link with commercial activities. However further study is needed to determine the change in merchants’ status in Kucha resulting from the construction of Kizil caves and the mural paintings about commerce inside.

References

[1]. Ban Gu. (209BCE). Han Shu

[2]. Jinxin Li. (2009). Sichou Zhilu Zongjiao Yanjiu (Xinjiang People's Publishing House).

[3]. Walter, M.N. Tokharian Buddhism in Kucha: Buddhism of Indo-European Centum Speakers in Chinese Turkestan before the 10th Century C.E.

[4]. Subai. (2019). Zhongguo Shikusi Yanjiu.

[5]. Trombert, É.A. du texte. (2000) Les manuscrits chinois de Koutcha : fonds Pelliot de la Bibliothèque nationale de France.

[6]. Casalini, A. Towards a new approach to the study of the Buddhist rock monasteries of Kuča (Xinjiang), 19.

[7]. Albert von Le Coq. Die Buddhistische Spätantike in Mittelasien, 7 vols.

[8]. Sun, R. (2023). Cultural Connections Between China and Foreign Civilizations Through the Kucha Donor Images in the Kizil Caves.

[9]. Ebert, Jorinde. The Sasanian and Other Civilizations' Impacts on Clothing of Royals in the Tarim Basin from The Stories of Kucha Queen Svayamprabha. 2nd ed.

[10]. Xinjiang Grotto Research Institute. (2015). Xiyu Bihua Quanji Kezier Shiku Bihua, vol. 2, 128.

[11]. Ahmad Hasan Dani and B. A. Litvinsky, Dilberjin Fresco. (1996). photograph, History of Civilizations of Central Asia: The crossroads of civilizations, A.D. 250 to 750, UNESCO.

[12]. Xuanzang. Xuanzang’s Record of the Western Regions.

[13]. Qiuci Yanjiu Yuan. Qiuci Shiku Bihua Zhongde Shanyuai.

[14]. Translated by Samana Hui Kyaw. (445). Xianyu Sutra.

Cite this article

Zhang,M. (2025). Explore the Ancient Kucha: Connection Between Commerce and Buddhism. Communications in Humanities Research,70,23-28.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Interdisciplinary Humanities and Communication Studies

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Ban Gu. (209BCE). Han Shu

[2]. Jinxin Li. (2009). Sichou Zhilu Zongjiao Yanjiu (Xinjiang People's Publishing House).

[3]. Walter, M.N. Tokharian Buddhism in Kucha: Buddhism of Indo-European Centum Speakers in Chinese Turkestan before the 10th Century C.E.

[4]. Subai. (2019). Zhongguo Shikusi Yanjiu.

[5]. Trombert, É.A. du texte. (2000) Les manuscrits chinois de Koutcha : fonds Pelliot de la Bibliothèque nationale de France.

[6]. Casalini, A. Towards a new approach to the study of the Buddhist rock monasteries of Kuča (Xinjiang), 19.

[7]. Albert von Le Coq. Die Buddhistische Spätantike in Mittelasien, 7 vols.

[8]. Sun, R. (2023). Cultural Connections Between China and Foreign Civilizations Through the Kucha Donor Images in the Kizil Caves.

[9]. Ebert, Jorinde. The Sasanian and Other Civilizations' Impacts on Clothing of Royals in the Tarim Basin from The Stories of Kucha Queen Svayamprabha. 2nd ed.

[10]. Xinjiang Grotto Research Institute. (2015). Xiyu Bihua Quanji Kezier Shiku Bihua, vol. 2, 128.

[11]. Ahmad Hasan Dani and B. A. Litvinsky, Dilberjin Fresco. (1996). photograph, History of Civilizations of Central Asia: The crossroads of civilizations, A.D. 250 to 750, UNESCO.

[12]. Xuanzang. Xuanzang’s Record of the Western Regions.

[13]. Qiuci Yanjiu Yuan. Qiuci Shiku Bihua Zhongde Shanyuai.

[14]. Translated by Samana Hui Kyaw. (445). Xianyu Sutra.