1. Introduction

It is a common misconception that the establishment of the Silk Road during the Han dynasty was to promote interstate trade and commerce. Many believe that Zhang Qian started the Silk Road to enhance economic ties with Central Asia under the command of Emperor Wudi. However, this view tends to simplify the early functions of the Silk Road. The initial purpose of the Silk Road started by the Han dynasty, was to weaken and divide the Xiongnu Empire by forming diplomatic alliances with states in Central Asia. This strategic move, rooted in diplomatic and military necessity, was designed to erode the Xiongnu's power base and ensure the security of the Han Empire.

2. Early Han diplomatic strategies

In the early years of the Han dynasty, the empire was relatively weak, and its primary strategy for dealing with the powerful Xiongnu Empire was the policy of heqin (和親), or marriage alliances. However, this approach shifted dramatically during the reign of Emperor Wudi (140–87 BCE), when the Han began adopting more aggressive tactics. The diplomatic missions sent to Central Asia by Zhang Qian laid the groundwork for what would later be known as the Silk Road. This network of routes connecting China to Central Asia was originally intended to establish alliances and weaken the Xiongnu by cutting off their connections to other nomadic tribes and Central Asian states.

The Han dynasty's primary aim was not to create an avenue for trade but to gain strategic advantages. As recorded in Shiji, the Xiongnu leader, the Shan-yu, confronted Zhang Qian, stating: "The Yue-chi are located to our north; how is it possible for China to send envoys to them? If I wanted to send envoys to Yue [Kiangsi and Ch'okiang], would China be prepared to yield to us?"[1] This highlights the Xiongnu's awareness of Han's diplomatic strategy aimed at undermining their control through foreign alliances.

3. Zhangqian’s report analysis

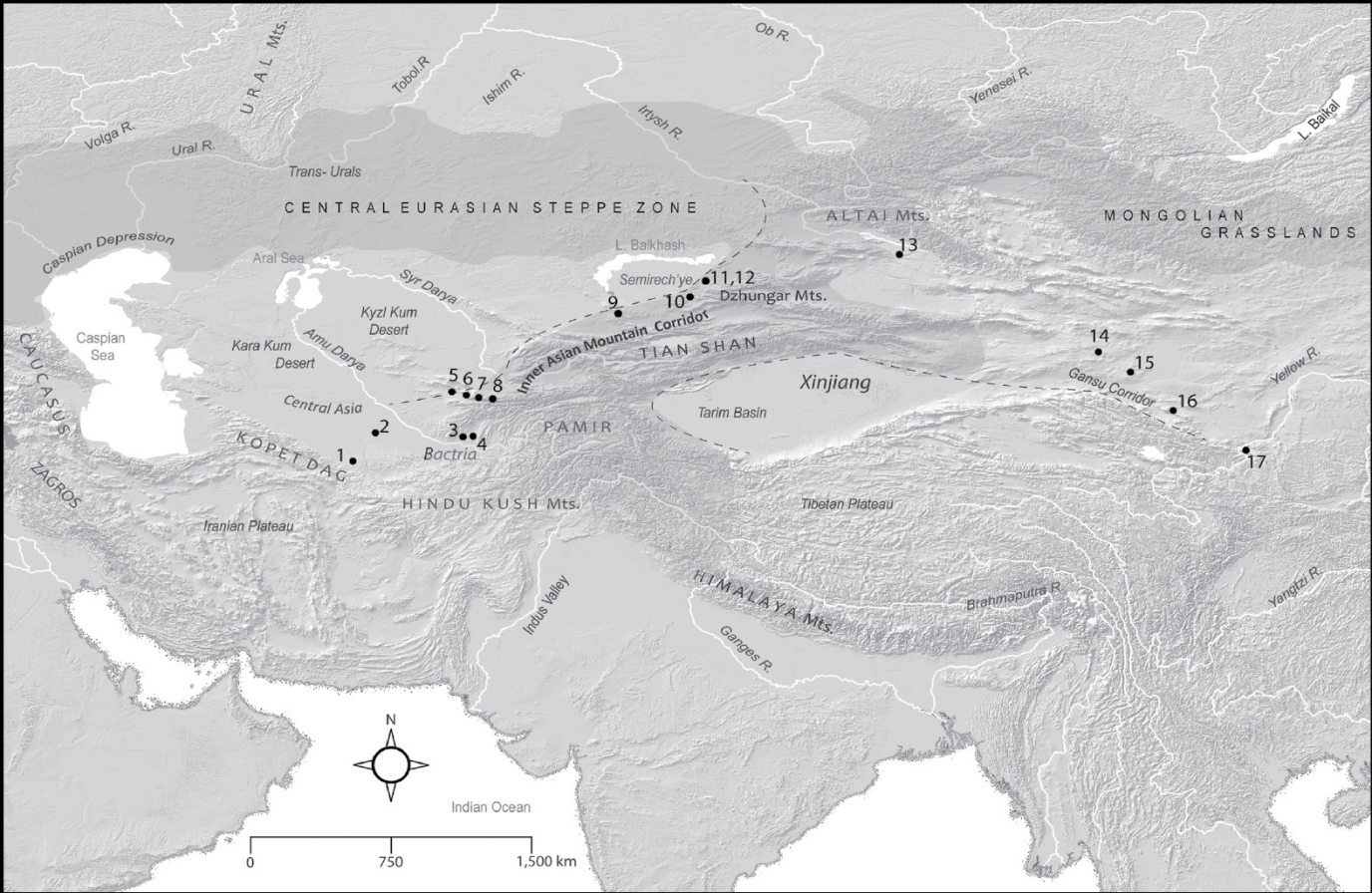

Zhang Qian’s reports, as documented in the Hanshu, provide valuable insights into the early diplomatic missions of the Han dynasty. Zhang Qian’s diplomatic journey to Ta-hia (Bactria) and other Central Asian states revealed that goods from China were already present in these regions, though not through direct trade with China. His discovery of Shu (Sichuan 四川) cloth in Ta-hia, which had been brought there via India, demonstrates that even before the formal establishment of the Silk Road, indirect trade routes already existed.[2] However, Zhang Qian’s mission was not focused on establishing trade but on creating diplomatic ties that would undermine the Xiongnu, and this recommendation highlights Han’s cautious yet strategic planning in ensuring diplomatic missions were successful and safe from interference by the Xiongnu.

Figure 1: Zhangqian’s routes for making diplomatic relationships with Ta-Hia(Bactria) [3]

Moreover, the Shiji account of the Xiongnu emphasizes that the Han court saw the Silk Road primarily as a tool to sever the Xiongnu's ties with their allied states. For instance, the Han’s marriage alliances, such as sending a Han princess to marry the Wusun ruler, were designed to sow discord between the Xiongnu and their allies. As recorded, in an attempt to cause a rift between the Xiongnu and the western powers that had previously helped and supported them, they had sent an imperial princess to wed the ruler of the Wusun people and established alliances with the Yuezhi people and Daxia (Bactria) farther west.

4. Role of the postal stations

The construction of military outposts along the Silk Road, such as the Xuanquan postal stations, was primarily for military and diplomatic purposes, as outlined in Jidong Yang's study of the Xuanquan Manuscripts. These stations were not built to facilitate trade but to ensure the safety and mobility of diplomats and military personnel, as well as to monitor population movements along the Han's borders.[4] Documents were required to pass through these stations, reflecting the strict control the Han government exerted over the movement of people.[5] The strategic positioning of military stations in the Gansu Corridor and beyond was crucial in ensuring the Han could sustain diplomatic relations with Central Asian states. The Hanshu also recounts that “previously, they were under the authority of the Xiongnu, but they grew powerful enough that, despite retaining a formal status as vassals, they declined to participate in court assemblies.” [6, 7] This description illustrates how the Han leveraged growing discontent among Xiongnu vassal states, encouraging them to align with Han interests.

Furthermore, Hanshu states that "China's interactions with the Western regions began during the reign of Emperor Wu-ti (140-87 B.C.). Initially, thirty-six kingdoms were established, but over time, they gradually split into more than fifty, all located west of the Xiongnu and south of the Wusun.”[8] This highlights the extensive diplomatic efforts of Emperor Wudi’s reign, which laid the foundation for the strategic use of the Silk Road to isolate the Xiongnu while opening relationships with Central Asian states.

5. Tang and Han Dynasty Silk Road

The role of the Silk Road evolved significantly from the Han to the Tang dynasty. While the Han primarily used the Silk Road for diplomatic and military purposes, the Tang government placed a much stronger emphasis on trade and commerce, as evidenced by their substantial infrastructure investments. The Grand Canal and the Tang government's reorganization of the larger canal system, which lowered the cost of shipping grain and other commodities, enabled trade throughout the interior of China. The Tang state managed approximately 32,100 km of postal service routes, which not only enhanced communication across the empire but also supported the expanding trade network.

This emphasized how the central government of the Tang court recognized the importance of commerce in connection with the Silk Road. The improvement of infrastructure and facilities within the empire reflects how commerce became a core priority, contrasting with the Han's earlier focus on diplomacy.

Despite the many foreign traders entering China during the Tang period, many travelers, including religious monks, noted the strict border control and dangers along the Silk Road. As the monk Xuanzang and others recorded, numerous checkpoints required travel permits, and banditry remained a persistent issue along the route, despite the strong Tang military presence This suggests that the overland Silk Road during the Tang period still faced significant dangers, even with the advancements in Tang military technology and increased postal stations. It highlights that 800 years earlier, the Han government, with its smaller and more limited control over the Silk Road, could only maintain safety across a smaller area. This limitation made the early Silk Road better suited for diplomatic missions rather than extensive trade.

Moreover, the Tang dynasty not only maintained control over the overland Silk Road but also greatly expanded maritime trade routes. Although Chinese envoys had been visiting India since the second century BC, a significant naval presence that reached the Persian and Red Seas and beyond was established during the Tang dynasty. Thousands of foreign merchants from diverse cultures, including Persians, Arabs, Indians, and others, flocked to Chinese cities to engage in trade. Guangzhou, in particular, became a bustling mercantile hub during this time.[8]

The Tang dynasty devoted significant resources to expanding its influence along both the overland and maritime Silk Road, which generated large profits through commerce with West Asia. This contrasted sharply with the Han dynasty's initial use of the Silk Road, which was focused more on diplomatic exchanges and military expeditions than on commercial profits.

6. Conclusion

The primary goals of the early Silk Road were to fortify the frontiers of the Han dynasty and to undermine the Xiongnu Empire via military and diplomatic means. To weaken the Xiongnu's power, Zhang Qian's expeditions and the formation of strategic alliances with Central Asian nations were essential. By strategically deploying their military might and using the Silk Road as a diplomatic instrument, the Han dynasty was able to weaken and split the Xiongnu, which ultimately helped them lose a war. Securing political and military control in Central Asia was the Silk Road's primary purpose under the Han dynasty, but trade and commerce would eventually come to characterize it during the Tang dynasty.

In contrast, the Tang dynasty embraced a broader Silk Road scope, incorporating overland and maritime routes. By expanding infrastructure, such as the Grand Canal, and strengthening their presence along the Silk Road, the Tang government sought to maximize trade profits, reflecting a shift from diplomacy to commerce. Unprecedented wealth resulted from the Tang dynasty's increased emphasis on commerce, which connected China to the Middle East, West Asia, and other regions. The Silk Road's purpose has evolved over time, and this fundamental change from political to commercial goals highlights the differences between the Han and Tang dynasties' use of this extensive trading network.

References

[1]. Sima Qian, Shiji [Records of the Grand Historian], trans. Burton Watson (New York: Columbia University Press, 1993), 54.

[2]. Ban Gu, Hanshu [Book of Han], trans. Homer H. Dubs (Baltimore: Waverly Press, 1938), 120.

[3]. Michael D. Frachetti and Timothy M. Earle, "Bronze Age Participation in a Global Ecumene: Mortuary Practice and Ideology Across Inner Asia," in Globalization in Prehistory, ed. Nicole Boivin and Michael D. Frachetti (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018).

[4]. Jidong Yang, “Transportation, Boarding, Lodging, and Trade along the Early Silk Road: A Preliminary Study of the Xuanquan Manuscripts,” Journal of the American Oriental Society 135 (2015): 421-432.

[5]. Xin Wen, The King’s Road: Diplomacy and the Remaking of the Silk Road (Princeton:Princeton University Press, 2023), 1-16, 201-225.

[6]. "The Han Histories" Silk Road Texts Project, University of Washington.

[7]. "Trade Under the Tang Dynasty" in World Civilization I, Lumen Learning.

[8]. "Internationalism in the Tang Dynasty (618–907)," Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, last modified October 2004.

Cite this article

Zhu,Z. (2025). The Early Function of Han Silk Road. Communications in Humanities Research,70,89-92.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Interdisciplinary Humanities and Communication Studies

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Sima Qian, Shiji [Records of the Grand Historian], trans. Burton Watson (New York: Columbia University Press, 1993), 54.

[2]. Ban Gu, Hanshu [Book of Han], trans. Homer H. Dubs (Baltimore: Waverly Press, 1938), 120.

[3]. Michael D. Frachetti and Timothy M. Earle, "Bronze Age Participation in a Global Ecumene: Mortuary Practice and Ideology Across Inner Asia," in Globalization in Prehistory, ed. Nicole Boivin and Michael D. Frachetti (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018).

[4]. Jidong Yang, “Transportation, Boarding, Lodging, and Trade along the Early Silk Road: A Preliminary Study of the Xuanquan Manuscripts,” Journal of the American Oriental Society 135 (2015): 421-432.

[5]. Xin Wen, The King’s Road: Diplomacy and the Remaking of the Silk Road (Princeton:Princeton University Press, 2023), 1-16, 201-225.

[6]. "The Han Histories" Silk Road Texts Project, University of Washington.

[7]. "Trade Under the Tang Dynasty" in World Civilization I, Lumen Learning.

[8]. "Internationalism in the Tang Dynasty (618–907)," Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, last modified October 2004.