1. Introduction

For millennia, humans have turned to religious activity for comfort, enlightenment, and fortitude. These practices are embedded in human culture, from students who carry religious amulets to the soccer field before an exam to athletes who cross themselves before a game. But do these religious superstitions really improve self-confidence?

Superstitions and religious rituals were believed to provide psychological benefits, from increasing resiliency to helping lower anxiety. Psychological theory holds that rituals, in fact, can help give people some degree of control over uncertain circumstances, boosting their mental health in the process. Although the influence of general superstitions on confidence and performance has been studied, little research has focused specifically on religiously inspired superstitions.

2. Literature review

Superstitious behavior is often linked to an individual’s desire for control, particularly in high-stress situations. [1]found that individuals experiencing higher levels of stress were more likely to engage in superstitious behaviors, suggesting that these rituals serve as a coping mechanism to mitigate anxiety and uncertainty. The theory also aligns with the illusion of control theory, which posits that people often overestimate their ability to influence uncontrollable outcomes through their actions. This effect is evident across various domains, including academic performance, sports, and decision-making.

Superstition has long been viewed through the lens of psychological theory. According to the illusion of control theory, people often overestimate their ability to influence events, particularly when outcomes are uncertain [2].Engaging in superstitious behavior offers a perceived sense of control, reducing anxiety and bolstering confidence.[3]

further explored this link by identifying superstitious behaviors as common coping strategies in academic environments. Their Safety Behaviors in Test Anxiety Questionnaire revealed that students frequently use religious or ritualistic behaviors to manage performance-related stress.[4] Similarly,found a strong association between trait anxiety and the likelihood of engaging in superstitious actions, suggesting a protective psychological function.[5]

3. Current study

More broadly, religious rituals have been associated with reduced anxiety and improved resilience. However, the overlap between religious practice and superstition is still debated, and empirical research focusing specifically on religiously motivated superstitions and their impact on self-confidence is scarce. This represents a significant gap in the literature.

While prior research has explored the role of general superstitions in performance and anxiety management, there remains a gap in understanding how religious superstitious behaviors specifically influence self-confidence.

The psychological benefits of religious practices — reduced anxiety, greater resilience — have been well documented over decades of research, but the effects of religiously superstitious behaviors on self-confidence are still a largely unexplored territory. Are such routines only placebo in their effects, or do they actually boost self-belief?

We aim to explore whether religious superstitious behaviors (like praying, wearing religious charms, or performing rituals) can boost a person’s general self-esteem.

The study offers the hypothesis that practicing religious superstition elevates self-esteem because it provides a contingency plan and reinforces the belief in divine help.

To trial the study, we will send out a survey measuring self-confidence levels after being involved in religious superstitious behavior. And if so, could people with religious faith get a better self-confidence?

The above is a brief summary of this research, which aims to open the work of religious superstitious behaviors as psychological tools that base laying a sense of self-confidence in people.

4. Methodology

Our study uses correlational design to find out the relationship between superstitious behavior and self confidence. Since our main objective is to check whether and to what degree these two variables are related, a correlational design is the most appropriate way to use. We have about 100 volunteers and the participants are all college students from University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, between the ages of 19-22. The criteria will be language proficiency that all participants should be able to read and respond to questions in English. In the study, superstitious behavior is the independent variable and self confidence is the dependent variable. Participants will complete a single online survey hosted on Qualtrics.

The survey includes religious superstitious behavior scale: Ten questions measuring behaviors related to prayer, charms, and personal routines believed to influence outcomes and self-confidence scale: Ten questions measuring participants’ perceived confidence in challenging situations. For the data, we use Cronbach’s α to determine the item's reliability. We also try to find out the mean, median, standard deviation, minimum and maximum of the data. The experiment includes histograms and plot graphs to determine their relationship. Correlation matrix is also included by using pearson’s r. For Ethical consideration, before starting the survey, participants will read a brief informed consent statement outlining the study’s purpose, procedures, and their rights as participants (including anonymity and the right to withdraw).

5. Result

The Cronbach’s α for the questions 1-10(4 is excluded)are 0.909. The Cronbach’s α for the questions 11-20(14 is excluded) are 0.901. In general, data from Cronbach's alpha shows that our questionnaire's items are internally consistent, meaning they often measure the same underlying notion in a trustworthy manner. Number of answers for the questions 1-20(4 and 14 are excluded) are 96. Mean, Median standard deviation of answers for the questions 1-20(4 and 14 are excluded) are shown below with the graphs.

Table 1: Descriptive statistics for religious superstitious behavior items (Q1–Q10, excluding Q4)

Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q5 | Q6 | Q7 | Q8 | Q9 | Q10 | |

N | 96 | 96 | 96 | 96 | 96 | 96 | 96 | 96 | 96 |

Missing | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Mean | 2.86 | 2.41 | 2.55 | 3.04 | 2.70 | 3.11 | 2.89 | 2.51 | 2.60 |

Median | 3.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 3.00 | 3.00 | 3.00 | 3.00 | 2.00 | 3.00 |

Standard Deviation | 1.41 | 1.46 | 1.51 | 1.34 | 1.42 | 1.45 | 1.25 | 1.26 | 1.41 |

Minimum | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

Maximum | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

Table 2: Descriptive statistics for confidence level items (Q11–Q20, excluding Q14)

Q11 | Q12 | Q13 | Q15 | Q16 | Q17 | Q18 | Q19 | Q20 | |

N | 96 | 96 | 96 | 96 | 96 | 96 | 96 | 96 | 96 |

Missing | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Mean | 3.14 | 3.46 | 3.25 | 3.22 | 3.21 | 3.43 | 3.52 | 3.54 | 3.76 |

Median | 3.00 | 4.00 | 3.50 | 3.50 | 4.00 | 4.00 | 4.00 | 4.00 | 43.00 |

Standard Deviation | 0.980 | 1.08 | 1.19 | 1.12 | 1.08 | 1.05 | 1.25 | 0.998 | 1.08 |

Minimum | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

Maximum | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

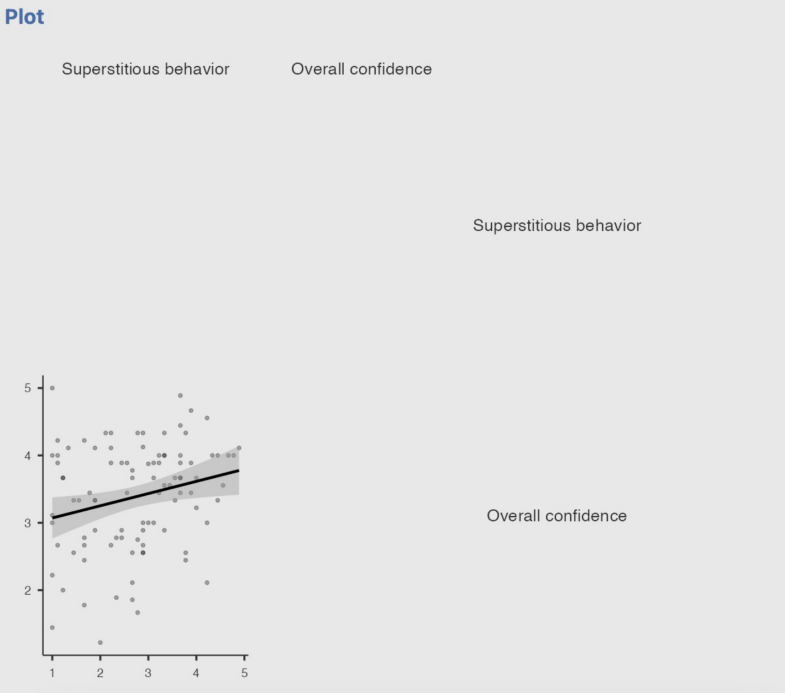

Minimum number of the questions 1-20(4 and 14 are excluded) are 1 and Maximum number of the questions 1-20(4 and 14 are excluded) are 5. The overall mean, median, standard deviation for superstitious behavior are 2.74, 2.83, 1.06 and for confidence are 3.39, 3.56, 0.802. The overall minimum, maximum number for superstitious behavior is 1.00/4.89 and for confidence is 1.22/5.00. For the correlational matrix, the pearson’s r of overall confidence is 0.240, df is 94, p-value is 0.019, and the Spearman’s rho is 0.228. Below is a graph of the correlation.

Figure 1: Overall summary statistic

The purpose of the study was to find out if religious superstitious practices enhance self-confidence. According to our hypothesis, people who practice religious superstition would feel more confident because they experience a perceived sense of divine support. Our findings supported this hypothesis, showing a positive association between religious superstitious practices and self-confidence (Pearson's r = 0.240, p = 0.019). This implies that doing religious rites, praying, or wearing religious charms can act as psychological support, making people feel safer in uncertain and important circumstances.

6. Conclusion

Although this study produced important insights into the relationship between religious superstitious behavior and self-confidence, in order to accurately comprehend the findings and lead future study, a number of limitations must be noted.

First, the correlational design limits the ability to draw conclusions about causality. While we found a positive relationship between religious superstitious behavior and self-confidence, it is unclear whether engaging in these behaviors actively enhances self-confidence or if individuals with higher self-confidence are more inclined to adopt such behaviors. It is also possible that a third variable—such as religious conviction, cultural background, or personality traits—may influence both. To clarify the direction of this relationship, experimental or longitudinal designs should be employed in future studies.

Second, generalizability is limited by the sample's homogeneity. Our participants were all undergraduate students aged 19–22 from the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. Differences that could occur in other groups are not included by this limited demographic profile. For instance, religious superstitions may be practiced differently on self-confidence by people of different ages, educational backgrounds, religious traditions, or professional circumstances. To improve the validity of the results, future research should use a more representative and varied sample.

Third, the study only used self-report measures, which are susceptible to bias in a number of ways, including self-perception bias and social desirability bias. Because they were worried about how their responses would be interpreted, participants could have overestimated their confidence or neglected their superstitious behavior. Behavioral observations, implicit measurements, and peer reports are examples of multi-method evaluations that may offer a more thorough and unbiased knowledge of the variables.

Despite these limitations, the results offer compelling evidence that religious superstitious behaviors may serve a psychological function—specifically, by enhancing an individual's self-confidence.Despite these limitations, the results offer compelling evidence that religious superstitious behaviors may serve a psychological function—specifically, by enhancing an individual's self-confidence. These results are consistent with established psychological theories, such as the self-efficacy hypothesis and the illusion of control, which contend that symbolic actions, even when they are not objectively successful, can increase self-confidence. In stressful situations, these activities may promote emotional comfort and self-assurance by acting as a perceived barrier against uncertainty.

In real life, counselors, educators, and mental health specialists should take note of these findings. Recognizing that people might find comfort in religious activities, including those that are viewed as superstitious, encourages a more comprehensive and culturally informed approach to mental health. For example, as coping mechanisms for anxiety, poor self-esteem, or performance pressure, therapists may bring up personal rituals or spiritual practices in therapy sessions—so long as they don't conflict with evidence-based treatments.

Future studies should build on these findings in a number of significant ways. First, religious superstitious conduct might be manipulated in experimental investigations to directly evaluate its effects on performance results and self-confidence. Second, cross-cultural comparisons might investigate how various religious traditions and belief systems influence the application and efficacy of superstitious activities. Third, to further understand why and how these activities affect self-belief, researchers should look at the mediating and moderating processes at play, such as the internal sense of control, anxiety reduction, or imagined divine help.

In conclusion, despite the fact that religious superstitions are sometimes written off as illogical or unscientific, the results of this study indicate that they could really have positive psychological effects, especially when it comes to boosting self-confidence. On the surface, something that seems nonsensical could actually be a reflection of ingrained psychological processes that support resilience, agency, and a sense of control. Gaining a deeper knowledge of how spirituality, religion, and ritual shape psychological functioning will require identifying these mechanisms.

References

[1]. Keinan, G. (2002). The effects of stress and desire for control on superstitious behavior. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 28(1), 102–108. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167202281009.

[2]. Rudski, J. M. (2004). The illusion of control, superstitious belief, and optimism. Current Psychology, 22(4), 306–315. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-004-1036-8.

[3]. Damisch, L., Stoberock, B., & Mussweiler, T. (2010). Keep your fingers crossed! How superstition improves.performance.Psychological.Science,21(7),1014.1020.https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797610372631.

[4]. Knoll, Ross W., et al. “Development and Initial Test of the Safety Behaviors in Test Anxiety Questionnaire: Superstitious Behavior, Reassurance Seeking, Test Anxiety, and Test Performance.” Assessment., vol. 26, no. 2, 2019, pp. 271–80, https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191116686685.

[5]. Futrell, B. (2011). A closer look at the relationship between superstitious behaviors and trait anxiety. Rollins Scholarship Online. https://scholarship.rollins.edu/rurj/vol5/iss2/5/ .

Cite this article

Wang,C. (2025). The Power of Faith: How Religious Superstitious Behavior Influences Self-Confidence. Communications in Humanities Research,67,183-187.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of ICLLCD 2025 Symposium: Enhancing Organizational Efficiency and Efficacy through Psychology and AI

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Keinan, G. (2002). The effects of stress and desire for control on superstitious behavior. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 28(1), 102–108. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167202281009.

[2]. Rudski, J. M. (2004). The illusion of control, superstitious belief, and optimism. Current Psychology, 22(4), 306–315. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-004-1036-8.

[3]. Damisch, L., Stoberock, B., & Mussweiler, T. (2010). Keep your fingers crossed! How superstition improves.performance.Psychological.Science,21(7),1014.1020.https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797610372631.

[4]. Knoll, Ross W., et al. “Development and Initial Test of the Safety Behaviors in Test Anxiety Questionnaire: Superstitious Behavior, Reassurance Seeking, Test Anxiety, and Test Performance.” Assessment., vol. 26, no. 2, 2019, pp. 271–80, https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191116686685.

[5]. Futrell, B. (2011). A closer look at the relationship between superstitious behaviors and trait anxiety. Rollins Scholarship Online. https://scholarship.rollins.edu/rurj/vol5/iss2/5/ .