1. Introduction

Palliative and hospice care, the specialized provision of physical, psychological, social and spiritual care to end-of-life patients and their families, was introduced to China in the late 1980s. With China entering the era of population aging, the quality of end-of-life care began to draw government and public attention. In 2017, China’s National Health and Family Planning Commission (NHFPC) issued a document to unify varied terminologies into “Anning Liaohu” (hospice care, HC). Also in that year, NHFPC issued three documents regarding hospice care, and designated four cities/districts to be the first batch of national HC pilot projects. The development of HC in China has been quickened up since. However, compared to many developed countries and regions, the HC practice in China is still at the early stage of development, with limited resources. Home HC is still rare, and most patients admitted to HC wards are very close to their life end.

As an integral part of HC internationally, HC family meetings are participated by the HC team and the patient family, aiming to exchange information about the patient's condition and negotiate care plans. Research has shown that such meetings play an important role in alleviating negative emotions of patients families, fulfilling patients' wishes, and achieving peace [1]. In the Chinese context, HC family meeting has emerged as a new “activity type”[2,3]or new “genre” in the HC field [4]. These meetings are often led by attending physicians, participated by HC team members such as nurses and social workers, and patients’ family members. Patients themselves are invited, but will participate only when they are conscious, in good-enough physical condition, and willing.

In Chinese culture, typically “high-context” [5] regarding communication style, high ranking on “power distance” and low on “individualism” [6], death is traditionally a discursive taboo; Confucius’ teaching in Analects, “How can one know death without knowing life?” is taken as rationale for death talk taboo. Even today, talking about death and planning the remaining life is very difficult. Death related decisions are commonly made late by the family, not known to the dying individual. There is a need to develop "death discourse literacy" [7], the competence and practice of verbalizing death and dying issues in various discourse forms, and constructing meanings of death, hence life. In the HC field, this literacy involves how medical teams bring end-of-life issues to the table for discussion with patients and families, and how patients and families effectively interact with the HC team to achieve peace in both life and death.

Research on HC family meetings in China started late [8,9], but recent years have seen breakthroughs, with case reports and intervention-based studies[10-12]. Discourse studies examined the structure, speech acts, and identities of presiding physicians, as well as challenges and coping strategies [13,14]. However, research on micro-level interaction is still lacking, especially from multimodal discourse perspectives. Most existing studies focused on the medical team, while interactions between participating parties need to be explored.

By using Norris's [15,16] multimodal analysis framework, this study examined interactions between the HC team and the patient family, especially their use of multimodal resources. The research questions were:

1.What "higher-level actions" (communication phases for particular functions) did the meeting go through to reach care decisions? What were their functions, and what result was achieved?

2.In each higher-level action, what modal resources did the presiding doctor and primary decision-making family member use? What were their "modal configurations" (hierarchical structures of the importance of each modality) and “modal densities”?

3.What identities did the doctor and the primary decision-making family member demonstrate and/or construct in various higher-level actions through the use of multimodal resources? What kind of “death discourse literacy” did they display?

2. Research methods

2.1. Corpus

The research corpus came from a hospice ward in a Beijing hospital, which is among the first batch of national HC pilot sites. Since the establishment of the ward in March 2017, family meetings have been a routine practice for each family. Participants include the HC team, all family members involved in decision-making, and patients who are willing and able to attend.

The primary corpus was a 50-minute video recording of an HC family meeting, filmed by a photographer who was also a HC volunteer, long before this research was conceived. The patient and family members respectively signed written consent forms, agreeing to the recording being possibly used for teaching, research, and public advocacy. Part of this recording was included in the anti-cancer documentary Sheng Sheng (Live the Life), Episode 2 [17]. The meeting was filmed by two cameras: one capturing a wide-angle view of the interactions; the other focusing on close-ups of the current speaker or listener. The two camera recordings were later integrated. A group photo of the ward wedding from Sheng Sheng was also included, as supplementary data.

The patient in this case, Luke (pseudonym), was a 53-year-old man with advanced colon cancer. After admitted to HC, his symptoms were fairly well controlled, and his greatest wish was to witness his son’s wedding, but his illness progression made fulfilling this wish difficult. Luke's family meeting was held in the activity room of the HC ward, one day in April 2019. Participants included three members of the medical team: the physician/ward director and two male volunteer social workers; and two family members: the patient's wife and son, Mike (pseudonym).

2.2. Analytical framework

The study has adopted Norris's[15,16]multimodal analysis framework. Following Vygotsky, Norris proposes that people as social actors use various mediating means or cultural tools to act or interact, referred to as "mediated action." Actions are always mediated and often involve multiple mediators, though not necessarily consciously. There are three types of mediated actions: (1)"lower-level mediated actions," the smallest units with pragmatic meanings, e.g., a gesture; (2) "higher-level mediated actions," composed of a series of lower-level actions, e.g., a cellphone voice interaction. Higher-level actions can include sub-level higher-level actions. (3) “Frozen actions,” completed by previous actions and contained in objects or environments, e.g., a house.

"Modal configuration" refers to the hierarchical structure of the importance of the lower-level actions that constitute a higher-level action. For example, in an academic lecture, language may be more important than gestures and postures; in an experimental demonstration, experimental items and actions may be more important than language. "Modal configurations" are used to analyze the structural distribution of modal resources in a higher-level action.

“Modal density” refers to the modal intensity and/or the modal complexity through which a higher-level interaction is constructed. This concept enables investigation of simultaneous higher-level action construction, and is often related to the amount of attention and awareness. For instance, sending a WeChat message on cellphone utilizes high modal density, involving the modes of object, object handling, gaze, and language, while transmitting the same message in person may utilize medium modal density, using modes such as posture, gesture, proxemics, and language. The latter may involve less attention and awareness.

2.3. Analytical procedure

First, higher-level actions (HLAs) in the entire meeting were identified. Second, major functions and modal configurations of the presiding physician and primary decision-making family member were identified for selected HLAs. Third, interaction episodes from various HLA were selected for linguistic transcription and image annotation, and analyzed in terms of multimodal resources used and communicative ends achieved. In addition, based on the "discourse analysis beyond the speech event" approach [18], the implementation result of the family meeting decision was briefly presented. Finally, identities and modal densities of the two parties through major HLAs were conceptualized, also their respective death discourse literacy.

3. Findings

3.1. Discourse structure in terms of higher-level actions

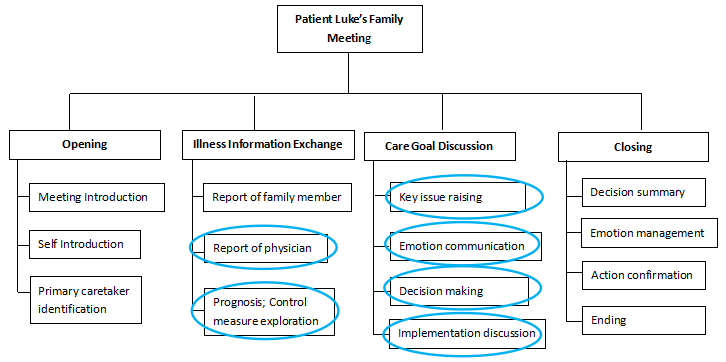

The family meeting included two major layers of HLAs (Fig. 1): the first layer aligned with the 4 major stages identified in previous research, i.e., the opening, communication of the condition, discussion of care goals and strategies, and closing [13]. The second layer consisted of specific HLAs under these 4 stages. At the opening stage, the presiding doctor introduced the meeting routine and two main tasks, invited participants to introduce themselves, and identified the primary family member who was best informed about the condition. At the communication of the condition stage, the doctor first invited the informed family member to report the medical history, and the patient’s son Mike took the task. The doctor supplemented with the current condition, pointing out its severity, and Mike explored the possibility of symptom control. At the discussion of care goals and strategies stage, the doctor raised the core issue, i.e., the patient's condition might not allow him to fulfill the wish of seeing his son's wedding. Mike expressed regret, and proposed the bride and groom visit in wedding attire. The doctor further constructed this proposal into a special “ward wedding,” and all participants joined to enrich its implementation plan. At the closing stage, the doctor summarized the ward wedding plan, Mike managed emotions and confirmed immediate action. The following analysis will focus on the second-layer HLAs highlighted inFigure 1.

3.2. Modal configurations of the presiding doctor and primary family member

3.2.1. HLC: Providing and obtaining medical information

In the HLA of doctor briefing the medical condition, the doctor's task was to fully inform the family about the patient's medical condition, making them aware of its severity. The family’s task, on the other hand, was to obtain full information of the patient’s condition. In this HLA the modal density of the doctor was high, while that that of the primary family member was low (Table 1).

|

Doctor |

Mike |

|

|

Function |

Providing medical information |

Obtaining medical information |

|

Modal Configuration |

layout > images, object handling > gesture, language > gaze |

language > gestures > gaze |

|

Modal Density |

High |

Low |

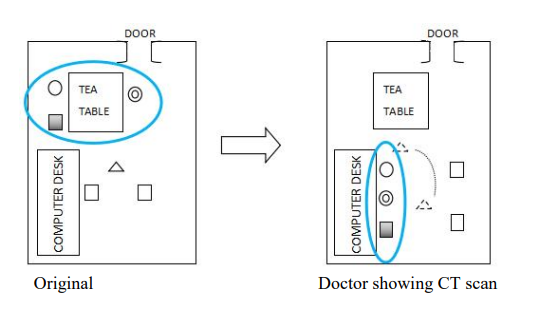

After Mike introduced his father’s medical history and condition, he said, "I don't know the results of this CT scan," hoping to gain a more specific understanding of the condition. The doctor responded, "I think it's necessary to show you his CT scan," and led Mike and his mother to the computer desk. The spacial layout therefore changed(Fig. 2).

In Table 1, the resources in modal configuration were ranked in terms of prevalence or importance, from left to right. For the doctor, the layout change—leading the family to the computer desk was the most important for her information delivery. This was followed by the CT scan images on the computer screen, a frozen action, the factual basis to be interpreted, and object handling—using the mouse to show varied CT images. The object handling allowed the family to see the patient's organs from different angles. The screen display was supplemented by gestures and verbal explanations, and less importantly, gaze shift between the screen and family members.

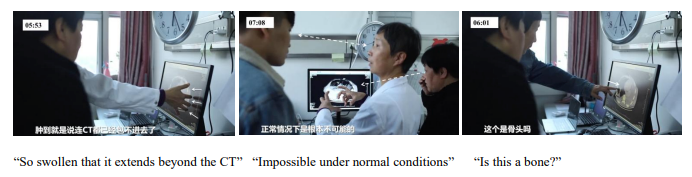

For specific images, the doctor used various gestures and verbal expressions to explain the condition. Some gestures were indexical, pointing out areas with pleural effusion to explain intestinal gas; some are metaphorical, using five fingers to scoop inward to indicate the intestine was so swollen that it looked like a "large water balloon" or "large water sac" (Fig. 3 left). Finally, the doctor used eye contact to communicate with Mike (center), expecting his understanding.

Mike was actively receiving information. Apart from verbally acknowledging information reception, “I see,” he sometimes asked clarification questions, with a gesture pointing at the CT image: “Is this a bone?” (right) or without gestures: “How long will this process take?”

3.2.2. HLA: Exploring control measures, giving prognosis, and raising the key issue

After reading the CT scan, the meeting parties returned to the original layout, seated around the tea table. Mike asked for possibilities of symptom control, hoping to sustain Luke’s life. The doctor spelt out the pessimistic disease course and raised the difficult key issue., i.e., the patient might not live long enough to witness his son’s wedding. Language was the most prevalent resource for both parties. While the modal density of the doctor was quite high, that of Mike was medium (Table 2).

|

Doctor |

Mike |

|

|

Function |

Predicting the pessimistic course of disease development; raising the key issue |

Exploring control measures |

|

Modal Configuration |

Language > gesture, facial expression, body language > paralanguage |

Language > gesture > gaze |

|

Modal Density |

Medium to high |

Medium |

Episode 1. 11:07-13:02

Doctor: So his current condition (clicks tongue) is quite dangerous. I'm not sure how long he can hold on.

Son: (3 seconds) Hmm~, (shifts downward gaze to the doctor) can his exudate and bloating be alleviated through some means? I’m not talking about a cure, just to alleviate, because cure…

Doctor: You mean to make him more comfortable, is that what you mean?

Son: Yes, more comfortable, or perhaps slightly extend his life, because major surgeries and such are too extreme. He can't accept it. He definitely can't.

Doctor: I understand.

Son: So is there a way to drain some fluid or gas, or improve eating, as you mentioned?

Doctor: Actually, (inhales, frowns, shakes head, clicks tongue) the next step in his infection is what we call septic shock, which is clinically very serious. It's fatal. When it comes to such shock, from a treatment perspective, he has to be given a lot of fluid, which requires a trial process. If this is not done, his blood pressure will drop quickly, and the person will, will pass away. If you give it, he might be sustained for a little longer, but that's not the main point now. I know he came here with a very strong wish, to live to attend your wedding.

Son: Yes.

Doctor: After seeing the CT scan today, I feel very pessimistic.

Son: (Chokes up) I understand. He might not make it to that time.

Doctor: This possibility is quite high. If that's the case, what should our strategy be? I would like to ask for your opinion. Do you think we should tell him about this?

In conversation Episode 1, Mike proposed possibilities for draining fluid, gas, and assisting with eating. To soften his suggestion or request, he used the disclaimer "not ... a cure, just to alleviate," aligning with HC principles and making it easier to accept. The doctor used high-degree adverbs and adjectives to form negative appraisal ("very serious," "fatal," "very pessimistic"), as well as high-probability modality ("the possibility is quite high"), to predict the dim future, allowing Mike to accurately receive the information: "I understand. He might not make it to that (wedding) time."

If the prominent function of verbal actions was accurate delivery and reception of information, then gestures, facial expressions, and paralanguage played a strong auxiliary role, highlighting the severity of the condition, the limitations of medical means, and emotional engagement of both parties. Figure 4 shows a contrast between Mike’s non-verbal cues of disease control, and the doctor’s doubts about this. Mike used many gestures to enhance his verbal expression, including opening his hands and moving them outward (Fig. 4 top left) to indicate draining, and clenching fists (top center) to indicate control. On the other hand, when talking about the severity of the situation, the doctor scratched her head and frowned six times (top right). She also used paralinguistic means such as slowing down her talking pace, pausing, and signing. In later interactions expressing the same idea, she kept a tight-lipped, frowning, downward-gazing expression (bottom left), made a downward gesture (bottom center), and shook her head three times with a serious facial expression (bottom right), reinforcing the uncertainty expressed verbally: "Whether it’ll really go as we hope to sustain his life, we actually don't know."

The modal densities in this HLA were at the medium range for both parties, prioritizing language supplemented by non-verbal modes. The doctor modal density was a bit higher than Mike’s, whose position was primarily receiving and processing information, though with efforts of tentatively exploring control measures. With her medical expert power, the doctor was firmly engaged in stressing the condition and challenge severity, using richer body language and paralanguage.

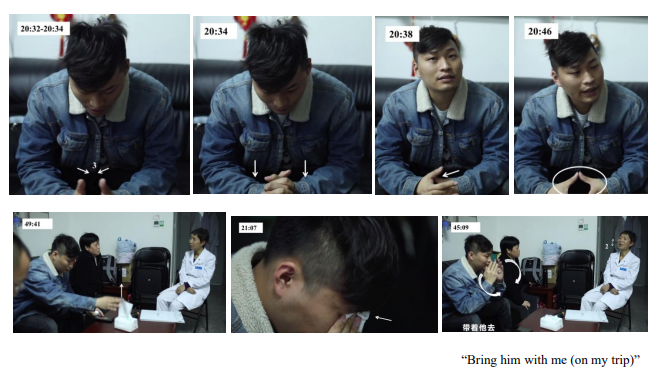

3.2.3. HLA: Expressing and empathizing emotions

At the stage of discussing care goals and strategies, there was a HLA focusing on emotions. Mike openly expressed regret over the potential inability to fulfill his father's wish of seeing him get married. The doctor listened to and empathized with his emotional discharge. Mike’s modal configuration was very rich and his model density was higher than that of the doctor (Table 3).

|

Doctor |

Mike |

|

|

Function |

Listening and empathizing |

Expressing emotions |

|

Modal Configuration |

Body language, facial expression > language, object, gaze > silence |

Language, paralanguage > gaze, gesture, facial expression > object, object handling, body language |

|

Modal Density |

Medium |

High |

Episode 2. 19:58-21:19

Doctor: So I'd like to hear your opinions, as you two know him best.

Mike: (Looks down) Mmm

Doctor: I don't know what choices he would make if he knows (Mike looks up at the doctor) that the situation is uncontrollable,

Mike: Mmm

Doctor: what choice he would make.

Mike: (Looks down, bites lips, and pauses for 4 seconds) Mmm. He should be able to, (looks up at the doctor) he should be able to accept the fact.

Doctor: You think he might—

Mike: (Looks down) But his greatest regret would be, if I told him he might (looks up at the doctor) not make it, (looks down) he might (looks at the doctor) break down. (Looks down) I think he might (looks at the doctor) feel despair. (Looks down, bites lip, taps fingers together three times, interlocks fingers tightly, and sighs)

Doctor: So what do you think we should do about this—

Mike: (Looks up) Because just now (smiles) I was talking to him (left hand pinches right hand), (looks down) and he uttered a few words, saying that he felt he was changing a lot every day. (Looks down, fingers form a ring, sighs, clicks tongue, and chokes) He was saying, "Why can't (looks at the doctor) you give me a couple more days?" (Looks down, looks up and sighs, takes tissue, wipes tears, and chokes) Actually, I also feel very regretful, if he really (looks at the doctor) can’t make it (looks down). It's just a few days. Alas! (Sighs, and wipes tears)

Episode 2 and Figures 5 show how emotions were expressed through rich modalities. When the doctor delivered the bad news that the condition was not controllable for long, Mike frequently used back-channeling "Hmm," indicating he was attentively listening and processing the information. His gaze constantly shifted among the doctor, the floor, and the ceiling, indicating he was moving between external communication and internal exploration. He used explicit affective words like "break down," "despair," and "regretful." When mentioning his father's potential despair, he paused verbally, looked down, and used rich gestures: tapping fingers inward three times (Fig. 5 top left 1), interlocking fingers and pressing down (top left 2). Later, when verbally conveying his father's reluctance and regret, his left hand pinched right hand (top left 3), and forming a ring with fingers (top right). Paralinguistic modalities were also very rich in this episode, including multiple sighs, tongue clicks, and choking up. For instance, when conveying his father's regret, Mike noticeably exhales outward, clicks his tongue, and chokes up. Conveying his father's anticipated despair was also expressing his own anticipated regret, guilt, and sadness.

Taking paper tissues to wipe tears (bottom center) was not merely a gestural modality. First, the tissue as an “object” was part of the environment and a “frozen action” participating in the live human interaction. Its central presence and placement on the table (bottom left) meant that family meeting participants were allowed to cry and openly express emotions in this holding environment. Against this was the Chinese cultural belief “Men do not easily she tears.” Second, the "object handling" of taking tissues was Mike's proactive use of the holding environment. The doctor and social workers present did not offer tissues to family members (which sometimes happened in family meetings). Mike, after verbally expressing his emotions in Episode 2, took tissues to wipe his tears (bottom center), demonstrating his autonomy in emotion display and management. A similar situation occurred later when discussing post-death arrangements. Mike stated that he wanted to turn his father's ashes into a crystal, and carry it with him on trips to show his father the world he hasn't seen. This verbal expression was also accompanied by taking tissues to wipe tears (bottom left). This action combines multiple modalities: object, object handling, gesture (bottom right), facial expression, and body language (leaning forward).

The doctor listened attentively to Mike’s expressions, by leaning forward her head (Fig. 5 bottom left). When Mike stated what he would do about his father’s ashes, “My father had a hard life, and he has not visited many places. So when I go somewhere in future…,” the doctor joined him to complete this sentence, “you will bring him with you.” While listening to this part of Mike’s story, the doctor kept close contact with him, and nodded nine times (bottom right).

Similarly in expressing deep empathy later (45:36-47:38), the doctor marveled at the patient’s eating: “I gasp with admiration. I can imagine how painful he felt, but he was forcing himself to eat under such pain. He must have a very strong supporting force.” Both the son and the wife said the patient claimed pretty good appetite. The doctor frowned an unbelievable facial expression, turning to social workers; “That’s strange. His intestines are swollen like that. Where does his appetite come from?” One of the social workers responded; “It seemed that he chose to eat for his loved ones, not for himself. He wanted to let you know he was OK.” When empathy was extended from the doctor to the whole HC team, it was also deepened. At this point Mike shed tears again.

In sum, in this HLA of emotion communication, Mike was the most active agent, letting out his strong feelings by using multiple modes, his modal density being high. The doctor listened attentively to his discharge, with synchronous nodding body language, eye contact, and silent companionship, expressing empathy and appreciation.

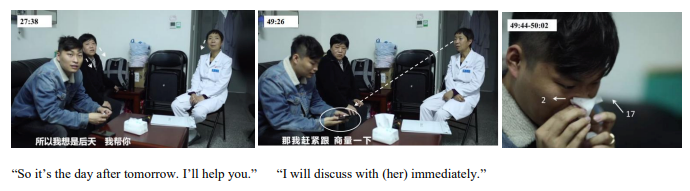

3.2.4. HLA: Proposing and constructing a creative solution

After fully understanding the condition and expressing emotions, Mike tentatively proposes the idea of a ward visit with wedding attire. The doctor built on Mike's proposed idea, and the two parties co-constructed a creative solution -- a special wedding in the ward. In this HLA of idea formation, unlike the previous one, language dominated. Mike took the initiative and his modal density was high, while that of the doctor was medium (Table 4).

|

Doctor |

Mike |

|

|

Function |

Building on the solution idea |

Providing a solution idea |

|

Modal Configuration |

Language > paralanguage |

Language > gaze, facial expression > gesture > object, object handling, paralanguage |

|

Modal Density |

Medium |

High |

Episode 3. 21:40-22:28

Mike: I don't want him (looks up at the doctor) to feel too much regret, (looks down) so from my perspective, I might still want (looks up at the doctor) to tell him the truth.

Mother: Yes.

Doctor: Mm-hmm

Mike: (Looks down) To tell him the truth, and then I'll see if there's any way to make him (looks up at the doctor) not feeling that regretful (looks down, wipes tears with tissue).

Doctor: Mm-hmm

Mike: For example, just now my wife called. I think I might want to discuss it with her later (sniffles)...

Doctor: Mm-hmm

Mother: (Interjects) He's had this illness for three years, after all. He's had this illness for long.

Doctor: (To mother) Yes.

Mike: (Turns head down, sniffles) Is it possible that, for example, I wear my clothes (looks up at the doctor) for the ceremony that day, (looks down) and have my wife (looks up at the doctor) wear her wedding dress and come over, to let him have a look?

Doctor: Hmm, you mean to hold a wedding especially for him in the ward ?

Mike: (Smiles, nodding)

Doctor: Sure, that’s OK.

Mike: (Looks down) Yes.

Doctor: (To mother) ...What do you think of your son’s idea?

Mother: (Smiles, looking at son) Good.

Aiming to make his father "feel less regretful," Mike proposed a solution. The proposal was presented in an exploratory manner, using uncertain, inquiring expressions like "is it possible" and "for example." The proposal was definitely not at the level of a formal ceremony: having himself and his wife wear wedding attire and come to the ward for his father to "have a look." This low-key statement might meant uncertainty about whether the plan could be implemented, and reluctance to burden the ward. However, the doctor, who had been listening attentively with frequent back channeling “Mm-hmm”, immediately picked up this proposal, chiming in and framing it as "holding a wedding especially for him in the ward." Mike confirmed the idea with a smile (Fig. 6 center).

While verbalizing his tentative idea, Mike maintained direct eye contact with the doctor, with a determined expression. He also used gestures, like spreading his hands outward when mentioning wearing wedding attire to the ward (left). Additionally, there were actions related to emotional processing, such as wiping tears with tissues and sniffling.

The doctor further elicited the opinion of the mother, facilitating interaction between the two in decision making. The mother confirmed Mike’s proposal with a smile, and eye contact with her son, and Mike smiled back (right). At this point, the individual proposal became a collective decision of the family and the palliative care team.

In this HLA of solution construction, language was the most indispensable. Other modalities such as gestures, mainly served to support verbal expression. Sometimes dual channels operated simultaneously: verbal expression of rational action proposals, and non-verbal and paralinguistic expression of emotions. Mike used more varied modalities than the doctor; his modal density was higher than the doctor. This matches Mike’s leading role of active proponent, while the doctor played a supporting role.

3.2.5. HLA: Discussing decision implementation

After the decision was made, the doctor invited everyone to join discussing the details of decision implementation. The issues included the location, time, participants, and things to prepare. The social workers moved from the attention background to the foreground. The bride, a non-present participant, was indirectly involved as Mike contacted her via cell phone. Compared with the medium modal density of the doctor, Mike’s modal density was high, as he simultaneously managed his emotions and handled chores such as contacting his bride (Table 5).

|

Doctor |

Mike |

|

|

Function |

Leading the team to co-construct the implementation plan |

Co-constructing the implementation plan |

|

Modal Configuration |

Language > gaze > body language |

Language > gaze, gesture > object, object handling, facial expression, body language |

|

Modal Density |

Medium |

High |

Episode 4. 29:06-30:24

Doctor: Yes, so we'll move him (the patient) to the room next door.

Social Worker 2: What about the time, tomorrow or the day after?

Doctor: (Pauses for 24 seconds) Tomorrow might be a bit rushed (laughing)?

Social Worker 1: Is a talk with him needed first tomorrow (Mike looks at Social Worker 1, and seems unconsciously folds paper tissues), to find out what he thinks, and then tell him the present idea? Would today be too rushed? (Mike looks at the doctor)

Doctor: This needs to be communicated to him quickly.

Mike: (Looks down, then up at the doctor) I will go and tell him. (Looks down) Yes, I will go and tell him. (Pauses for 7 seconds, gradually looks up at the doctor) Should we invite my parents-in-law over? (3 seconds) To make it more formal, right? And then let him—(pauses for 8 seconds, looks up, thinks, purses lips and nods slightly four times)

Doctor: I think this depends on you, you might need to discuss it with your wife.

Mike: (Looks down) Yes, yes, I will call her and discuss it (purses lips).

(After detailed discussion, 48:58—49:29)

Doctor: (Looks at social workers) So let's do this: we'll tentatively set it for Wednesday. After the antibiotics are used tonight, (turns to Mike) we'll check his condition tomorrow morning. If he feels bad, (turns to social workers) we'll do it as it is, (turns to Mike) and change the time to tomorrow afternoon. We'll just have to follow his rhythm.

Mike: No problem, no problem.

Doctor: Okay, if it's possible, we'll tentatively set it for Wednesday morning. ...

Mike: Alright, I'll contact (the bride) to discuss it immediately.

Doctor: (Looks at Mike’s mother) Is there anything else, do you have anything else to discuss, anything you don't understand or want to know?

Mother: I understand everything.

The content discussion mainly used language, while interpersonal interaction connections were also realized with gaze and body language. The doctor looked at the two social workers off the camera screen, inviting them to view opinions on the specific time for the ward wedding. At this point, the family members still looked at the doctor. Social Worker 2, after stating the necessary preparations, suggested the wedding be held the day after, and the family's gaze followed the doctor to the social worker (Figure 6 left). After the plan was settled, Mike said he would contact the bride immediately and started operating his cell phone to make the call (center). At this point, the doctor looked at Mike's phone, leaning slightly forward (right).

Mike’s modal configuration was quite complex. His pauses for thought increased (Episode 4), and his gaze shifted between the off-camera social workers (Fig. 7 left), the doctor, upward, and downward at the phone (center), accompanied by significant head turns and nodding. This indicated an increase in his external interaction partners and the need for more internal thinking time. Taking tissues to sniffle repeatedly (right) might mean emotion management. On the other hand, his determined facial expression with pursing lips might reflect resolve. The decision was turning into action, as seen in the subsequent object handling of calling the bride.

The doctor's gaze frequently shifted between the social workers, Mike and his cell phone (the bride on the other end of the call), and the patient's wife. This shift suggested the diversity of participants and the collective decision-making. Her modal density was not as high as that of Mike, which might suggest responsibilities were shifted away or diffused from her at this stage.

3.2.6. Result of the family meeting: Ward wedding

After the meeting, Mike informed Luke about his condition, and asked his opinion on the ward wedding plan. Luke agreed. The wedding preparations proceeded as planned.

On the special wedding occasion, the groom and bride thanked their parents, the bride presented flowers to the father-in-law, and the doctor, on behalf of the HC team, gave blessings. Luke shed tears and said, "I have no regrets," "I am at peace." Luke witnessed not only the wedding but also the ceremony of life's continuation before his death. His wish was fulfilled, bringing peace to both life and death (Fig. 8) [17].

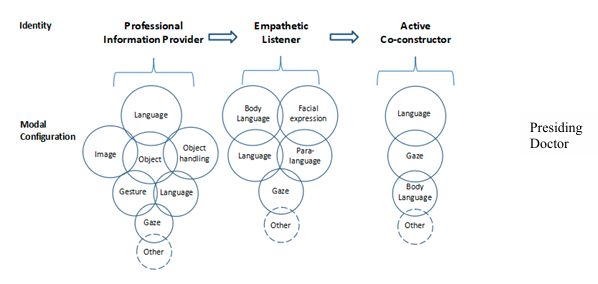

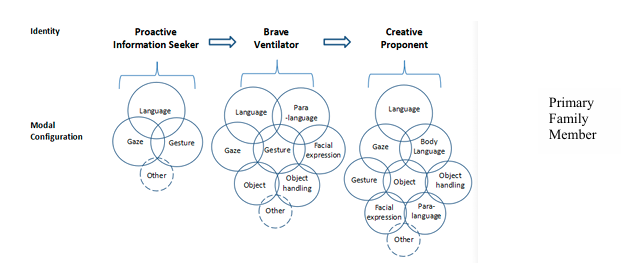

3.3. Identities and modal configuration features in different HLAs

The doctor and the primary family member Mike exercised different identities in varied major HLAs, or at different stages of the family meeting, i.e., information exchange (including the doctor’s information delivery, and the family’s exploration of control measures), emotion and will communication, and decision making (reaching a solution and implementation details). Their modal configurations and modal density are somewhat matched to those identities (Table 6).

|

Participant |

Information Exchange |

Emotion and Will Communication |

Decision Making |

|

|

Doctor |

Identity |

Professional information provider |

Empathetic listener |

Active co-constructor |

|

Modal Configuration |

Layout and object prevalent |

Body language prevalent |

Language prevalent |

|

|

Modal Density |

High |

Medium |

Medium |

|

|

Mike |

Identity |

Proactive information seeker |

Brave ventilator |

Creative proponent |

|

Modal Configuration |

Language prevalent |

Body language and paralanguage prevalent |

Language, body language and object prevalent |

|

|

Modal Density |

Low |

High |

High |

|

The doctor’s identity in the HLA of briefing the patient’s condition was that of a professional information provider. She moved positions, employed complex multimodal resources such as the layout and CT scan images to fully inform the patient’s fatal condition. While the primary family member was involved in emotion and will expression, she was an empathetic listener.

She sat still but used rich body language to show empathy. At the stage of decision making, including forming the solution and discussing its implementation, her identity was that of an active co-constructor, and her modal configuration was relatively simple, language being the most prominent mode. Although the presiding leader throughout, the doctor’s identity changed during the meeting process, from almost a lone speaker or informer, to a rather quiet listener, and then to a backseat organizer of open group discussion. Paradoxically, she had a leading role as the meeting chair, but merely a supporting role in the family’s crucial life event.

The patient’s son Mike was an proactive information seeker when he was informed about his father’s condition. While listening, he used simple, language prevalent modal configurations. He was a brave ventilator when expressing emotions and wills, employing complex body language and frozen action as well as language. At the decision making stage, his identity was that of a creative proponent; he tapped on varied modalities to express his idea. As a family member he demonstrated his agency in medical decision making to fulfil the patient’s wish, and the increase of modalities throughout the meeting process seemed to coincide with the enhancement of his agency.

Figure 9 shows identities and modal configurations of the two parties in different HLSs or at different stages. The circle size indicates degree of modal prevalence. A tendency was that while the doctor’s modal configurations decreased in complexity, those of Mike increased. This contrast seemed to coincide with their agency change: when Mike’s agency increased, the doctor to some extent retreated to the supporting background.

4. Conclusion

Through the analysis, the research questions can be answered as follows: In this family meeting, the HC team and the patient’s family reached the decision for a "ward wedding" through a series of HLAs, including exchanging information about the patient’s medical condition, raising the key issue to be tackled, communicating emotions, constructing a solution, and discussing decision implementation. The ward wedding, meant to satisfy the patient’s end-of-life desire, was successfully fulfilled.

The doctor’s modal configurations and modal density changed through HLCs. Her modal density was highest when briefing the medical condition. The extensive use of modal means such as s layout change and CT images helped to reveal the end-of-life reality. For HLCs of decision construction and plan discussion, she maintained medium modal density, mainly constrained to language and the body. As for the primary family member, the highest modal density was in later HLCs, i.e., emotion and will disclosure, solution proposal, and plan discussion. Objects and their handling, among others, helped to fulfil such functions. His modal density stayed at a low level when receiving information of the patient’s medical condition.

The use of multimodal resources, conscious or not, revealed and constructed the doctor's identities in varied HLAs: a professional information provider, an empathetic listener, and an active co-constructor of decisions. Likewise, Mike’s identities included a proactive information seeker, a brave ventilator of emotions and wills, and a creative solution proponent. The identities that the two parties constructed, or the practices that they performed, constitute part of their "death discourse literacy" [7]. The doctor’s death discourse literacy strengths lied in truthfully and meticulously informing about the terminal condition, deeply empathizing with the emotions and needs of the patient and family, and dialogically facilitating the family-proposed key issue solution. Mike’s death discourse literacy strengths lied in his agentive information seeking and effective processing, brave and open emotion and will disclosure, and creative solution proposal and negotiation with an expert team. These are particularly precious against the backdrop of China’s traditional cultural context of death discourse taboo, emotion suppression, and high power distance between medical professionals and common people. We hope that such death discourse literacy along with the new genre of HC family meeting will extend in future, which may in turn bring positive cultural change.

* Note: Two papers in Chinese were published using the case material in this presentation[19,20]. For this presentation the analytical framework is adjusted to focus on modal densities and identities of the doctor and the primary family member, and integrate data from the two sides. Efforts are also made to reorient the text to international audience/readers.

References

[1]. Cahill, P.J., Lobb, E.A., Sanderson, C. & Phillips, J.L. (2017) What Is the Evidence for Conducting Palliative Care Family Meetings? A Systematic Review. Palliative Medicine,31, 197-211.

[2]. Levinson, S.C. (1979) Activity Type and Language. Linguistics, 17, 356-399.

[3]. Sarangi, S. (2000) Activity Types, Discourse Types and Interactional Hybridity: The Case of Genetic Counseling. In S. Sarangi & M. Coulthard (eds.), Discourse and Social Life(pp.1-27). London & New York: Routledge.

[4]. Gao, Y.H. (2019). Genre Types of Death Discourse and Social Changes. Foreign Languages Research, 2019(2), 27-32.

[5]. Hall, E. T. (1976) Beyond Culture. Garden City, NY:Doubleday.

[6]. Hofstede, G. (1984) Culture's Consequences: International Differences in Work-Related Values. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

[7]. Luo, Z.P. & Gao, Y.H. (2023) Towards Death Discourse Literacy. Medicine and Philosophy,2023(8),19-23.

[8]. Zhao, W.J. & Huang, Z.(2018) Advances in Family Meetings for End-of-Life Patients. Journal of Nursing Science, 2018(19). 109-112.

[9]. Wang, M.M., Xu, T.M., Zhao M., & Yue, P. (2021) Assessment of the Clinical Practices of Palliative Care Family Meetings: A Systematic Review. Chinese Journal of Social Medicine, 2021(2), 227-232.

[10]. Liu, M., Zhang, F.L., & Zeng, T.Y. (2015) Effect of Medical Staff-Led Family Conference on Terminal Cancer Patient. Journal of Nursing (China), 2015(7),61-63.

[11]. Liu, M., Wang, C.S., Wang, S.J., & Zeng, T.Y. (2018) The Experience of Caregivers Participating in Terminal Cancer Patient’s Family Conferences: A Qualitative Study. Journal of Nursing Science, 2018(24),5-7.

[12]. Wang, M.M. (2021) A Study of Family-Based Interactive Intervention Program for End-of-Life Issues Between End-of-Life Patients and Their Family Members. Master’s Thesis, Capital Medical University.

[13]. Qin, Y. & Gao, Y.H. (2021a) Palliative-Care Family Meeting in a Chinese Context: Structure, Snags, and Strategies. Foreign Languages in China, 2021(4),54-61.

[14]. Qin, Y. & Gao, Y.H. (2021b) Palliative-Care Family Meeting in a Chinese Context: Speech Act Distribution and Physician’s Identities. Foreign Languages Research, 2021 (4), 38-45.

[15]. Norris, S. (2004) Analyzing Multimodal Interaction: A Methodological Framework. New York: Routledge.

[16]. Norris, S. (2019) Systematically Working with Multimodal Data. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

[17]. Youku China Population Publicity and Education Center. (2020) Sheng Sheng (Episode 2). https://v.youku.com/v_show/id_XNDg4MTYzNjUzMg==.html?spm=a2hbt.13141534.1_3.1&s=095cefbfbdefbfbdefbf&scm=20140719.apircmd.61517.video_XNDg4MTYzNjUzMg==

[18]. Wortham, S. & Reyes, A. (2015) Discourse Analysis beyond the Speech Event. London & New York: Routledge.

[19]. Gao, Y.H. & Qin, Y. (2022) Interactions of a Palliative (Hospice) Care Medical Team in a Family Meeting: A Multimodal Analysis. Journal of PLA University of Foreign Languages, 2022(6),1-10.

[20]. Qin, Y. & Gao, Y.H. (2022) Multimodal Analysis of Family Members’ Interaction Patterns in Palliative Care Family Meetings: The Case of “Wedding in the Hospice Ward.”Foreign Language and Literature Studies, 2022(3), 15-29.

Cite this article

Gao,Y.;Qin,Y. (2025). Multimodal Resource Use for Creative Solution Construction in a Chinese Hospice Family Meeting. Communications in Humanities Research,69,173-188.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Literature, Language, and Culture Development

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Cahill, P.J., Lobb, E.A., Sanderson, C. & Phillips, J.L. (2017) What Is the Evidence for Conducting Palliative Care Family Meetings? A Systematic Review. Palliative Medicine,31, 197-211.

[2]. Levinson, S.C. (1979) Activity Type and Language. Linguistics, 17, 356-399.

[3]. Sarangi, S. (2000) Activity Types, Discourse Types and Interactional Hybridity: The Case of Genetic Counseling. In S. Sarangi & M. Coulthard (eds.), Discourse and Social Life(pp.1-27). London & New York: Routledge.

[4]. Gao, Y.H. (2019). Genre Types of Death Discourse and Social Changes. Foreign Languages Research, 2019(2), 27-32.

[5]. Hall, E. T. (1976) Beyond Culture. Garden City, NY:Doubleday.

[6]. Hofstede, G. (1984) Culture's Consequences: International Differences in Work-Related Values. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

[7]. Luo, Z.P. & Gao, Y.H. (2023) Towards Death Discourse Literacy. Medicine and Philosophy,2023(8),19-23.

[8]. Zhao, W.J. & Huang, Z.(2018) Advances in Family Meetings for End-of-Life Patients. Journal of Nursing Science, 2018(19). 109-112.

[9]. Wang, M.M., Xu, T.M., Zhao M., & Yue, P. (2021) Assessment of the Clinical Practices of Palliative Care Family Meetings: A Systematic Review. Chinese Journal of Social Medicine, 2021(2), 227-232.

[10]. Liu, M., Zhang, F.L., & Zeng, T.Y. (2015) Effect of Medical Staff-Led Family Conference on Terminal Cancer Patient. Journal of Nursing (China), 2015(7),61-63.

[11]. Liu, M., Wang, C.S., Wang, S.J., & Zeng, T.Y. (2018) The Experience of Caregivers Participating in Terminal Cancer Patient’s Family Conferences: A Qualitative Study. Journal of Nursing Science, 2018(24),5-7.

[12]. Wang, M.M. (2021) A Study of Family-Based Interactive Intervention Program for End-of-Life Issues Between End-of-Life Patients and Their Family Members. Master’s Thesis, Capital Medical University.

[13]. Qin, Y. & Gao, Y.H. (2021a) Palliative-Care Family Meeting in a Chinese Context: Structure, Snags, and Strategies. Foreign Languages in China, 2021(4),54-61.

[14]. Qin, Y. & Gao, Y.H. (2021b) Palliative-Care Family Meeting in a Chinese Context: Speech Act Distribution and Physician’s Identities. Foreign Languages Research, 2021 (4), 38-45.

[15]. Norris, S. (2004) Analyzing Multimodal Interaction: A Methodological Framework. New York: Routledge.

[16]. Norris, S. (2019) Systematically Working with Multimodal Data. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

[17]. Youku China Population Publicity and Education Center. (2020) Sheng Sheng (Episode 2). https://v.youku.com/v_show/id_XNDg4MTYzNjUzMg==.html?spm=a2hbt.13141534.1_3.1&s=095cefbfbdefbfbdefbf&scm=20140719.apircmd.61517.video_XNDg4MTYzNjUzMg==

[18]. Wortham, S. & Reyes, A. (2015) Discourse Analysis beyond the Speech Event. London & New York: Routledge.

[19]. Gao, Y.H. & Qin, Y. (2022) Interactions of a Palliative (Hospice) Care Medical Team in a Family Meeting: A Multimodal Analysis. Journal of PLA University of Foreign Languages, 2022(6),1-10.

[20]. Qin, Y. & Gao, Y.H. (2022) Multimodal Analysis of Family Members’ Interaction Patterns in Palliative Care Family Meetings: The Case of “Wedding in the Hospice Ward.”Foreign Language and Literature Studies, 2022(3), 15-29.