1. Introduction

Architectural design goes beyond the construction of physical structures; it serves as a crucial medium for expressing cultural values and fulfilling environmental responsibilities. The design of a university campus reflects its core values, social obligations, and interaction with its natural surroundings. This paper offers a detailed comparison of the main axis architectural designs of the University of British Columbia (UBC) and Tsinghua University, focusing on differences and connections in spatial layout, cultural symbolism, and environmental sustainability.

The study argues that the main axis designs of UBC and Tsinghua University embody distinct cultural values and environmental consciousness through the integration of architectural and natural landscape integration. To support this analysis, two architectural theories are employed: the Unsettling Settler Colonial Framework and Palladio Virtuel [1-2]. The former examines how architectural spaces reshape historical narratives and promote social justice through spatial organization and cultural symbols, highlighting overlooked histories and cultural identities. The latter emphasizes that architecture is more than a functional structure; it is a symbol of societal values and cultural identity, exploring how design elements connect deeply with cultural traditions. This research holds both theoretical and practical significance. At the theoretical level, it contributes to understanding the interplay between architecture, culture, and ecological responsibilities, enriching academic discussions on campus design. Practically, the findings provide insights for university planners and architects seeking to design spaces that balance cultural expressions, functionality, and sustainability.

2. Geographical and spatial contexts of UBC and Tsinghua University

Before analyzing the main axes of UBC and Tsinghua University, it is essential to understand the geographical settings and overall campus layouts of these institutions.

UBC, located in Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada, situated on a peninsula along the Pacific coast. Its main axis begins at the Rose Garden, extends through the main square and teaching and research buildings, and ends at the Chan Centre for the Performing Arts. The axis features several iconic buildings, such as the modernist Irving K. Barber Learning Centre and the Vancouver Art Gallery, which incorporate transparent glass and natural lighting to emphasize harmony with the environment. Green spaces and sculptures flanking the axis symbolize the fusion of knowledge and culture. Influenced by modernist architectural principles, UBC prioritizes functionality and sustainability, crafted by internationally renowned architects like Arthur Erickson. His works, including the UBC Museum of Anthropology, showcase Canada’s Indigenous cultural heritage through a blend of concrete and wood. However, UBC's campus also reflects its colonial history. Built on the traditional territory of the Musqueam people, the university acknowledges its colonial past through symbolic Indigenous totem poles and commemorative installations that foster dialogue about colonial history and social justice.

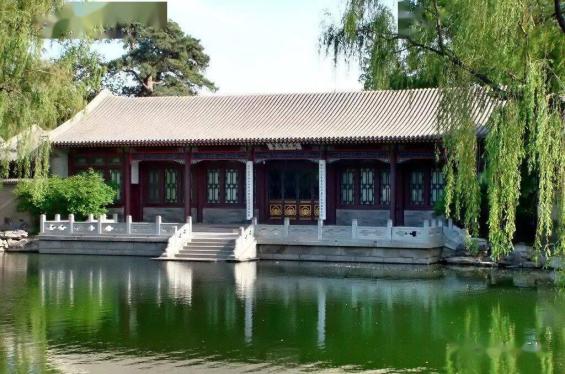

Tsinghua University is situated in the northwestern part of Beijing, China. Its main axis starts at the historical Tsinghua Garden Gate, extending to the Great Hall and the library. Academic buildings and traditional courtyards are symmetrically arranged along the axis, highlighting a classical Chinese emphasis on balance and order. Designed by architect Yang Tingbao, the Great Hall blends elements of traditional Chinese palaces and Western classical architecture, symbolizing dignity and academic authority. The campus design is deeply influenced by Chinese classical garden traditions, exemplified by the Shui Mu Tsinghua Garden, where lakes, stone bridges, and pavilions create a natural landscape that appears effortlessly harmonious. Historical buildings like Jinchun Garden and Gongzi Hall reflect Qing Dynasty imperial garden designs, symbolizing cultural heritage and educational missions. Although Tsinghua University’s development was not directly shaped by Western colonial rule, its early campus planning reflects China’s cultural positioning in the early 20th century amid international dynamics. Initially funded by the U.S. government as a symbol of Sino-American cultural and educational cooperation, the early campus architecture blends Chinese and Western elements, achieving a balance between modernity and traditional cultural revival. These two universities were selected for their representative cultural and environmental contexts, as well as the author’s personal experiences with their architectural designs and spatial functions.

3. Comparative analysis

3.1. Cultural symbols and architectural styles

The main axis buildings of UBC and Tsinghua University showcase different cultural and architectural characteristics, rooted in their respective historical and social contexts.

At UBC, architectural design emphasizes modern functionality and cultural integration. For example, the stepped glass facade of the Walter C. Koerner Library (Figure 1) symbolizes the "gateway to knowledge" while blending with the surrounding natural landscape [3]. Additionally, indigenous art installations like the "Welcome Figure" (Figure 2) highlight indigenous culture and history. According to the Unsettling Settler Colonial Framework, these installations reclaim marginalized cultural narratives, fostering awareness of cultural diversity and social justice [2]. UBC’s approach to cultural symbolism highlights the interplay between modernist architecture and the recognition of indigenous heritage, reflecting its commitment to inclusivity and reconciliation.

In contrast, the main axis buildings of Tsinghua University emphasize traditional Chinese culture and social order. The "Main Gate" of Tsinghua (Figure 3), a traditional stone structure, serves as a symbolic gateway to academic and cultural knowledge, representing historical resilience and cultural continuity [4]. Analyzing this through the Palladio Virtuel Theory, the symmetrical design of the gate demonstrates both aesthetic appeal and campus structural hierarchy [5].

Similarly, the Grand Auditorium of Tsinghua University (Figure 4) exemplifies solemnity and tradition through its grand symmetrical design and monumental style. As a venue for major academic and cultural events, its design embodies dignity and authority. According to Palladio Virtuel Theory, the Grand Auditorium’s architectural elements reinforce Tsinghua’s cultural heritage and its emphasis on social order and historical continuity.

3.2. Community interaction and social functions

The main axis layouts of UBC and Tsinghua University create different spaces for social interaction and community engagement, reflecting their cultural and institutional objectives.

At UBC, the arrangement of academic, administrative, and cultural buildings emphasizes inclusivity and collaboration. A prominnent example is The Nest (Figure 5), a student center serving as a multi-functional hub hosting events and fostering collaboration. Its central location encourages spontaneous social interactions among students [6]. Additionally, the "Reconciliation Pole" (Figure 6) on UBC’s campus commemorates colonial history and cultural renewal. According to the Unsettling Settler Colonial Framework, this installation encourages historical reflection and embeds indigenous memory into everyday campus life, enhancing cultural awareness [2].

In contrast, Tsinghua University’s main axis layout focuses more on formal events and institutional representation. The Grand Auditorium hosts international conferences, academic forums, and cultural events, symbolizing Tsinghua’s global influence and academic excellence [7]. Similarly, Gongzi Hall (Figure 7) follows a traditional courtyard layout, supporting academic discussions and cultural ceremonies. According to the Palladio Virtuel Theory, its enclosed yet open design reflects social hierarchy and cultural order, fostering both academic and social engagement.

3.3. Environmental responsibility and sustainable design

Both UBC and Tsinghua University value environmental protection, yet their approaches reflect different cultural and institutional perspectives. At UBC, environmental sustainability is central to its architectural and campus planning. The Centre for Interactive Research on Sustainability (CIRS) (Figure 8) exemplifies green building design, incorporating solar panels and a rainwater collection system to reduce energy consumption and pollution [8]. This infrastructure not only reduces the campus’s environmental footprint but also promotes innovation in sustainable design. UBC’s Botanical Garden (Figure 9) further enhances public environmental awareness through displays of natural ecosystems and conservation knowledge. Drawn from the Unsettling Settler Colonial Framework, UBC’s environmental design integrates sustainability with indigenous ecological knowledge, respecting traditional ecological practices [2].

Tsinghua University, on the other hand, emphasizes a harmonious relationship between built strcutures and the natural environment. The Shui Mu Tsinghua Garden (Figure 10), with its intricate water features, stone paths, and lush greenery, connects buildings with the natural environment [9]. Guided by the Palladio Virtuel Theory, this layered spatial design reflects a philosophical integration of humans and nature, highlighting environmental and cultural interaction. Additionally, Tsinghua’s Eco-Center (Figure 11) underscores the university’s commitment to sustainability. This facility serves as a hub for environmental research and education, embodying Tsinghua’s dedication to advancing ecological values.

3.4. Cultural expression and identity

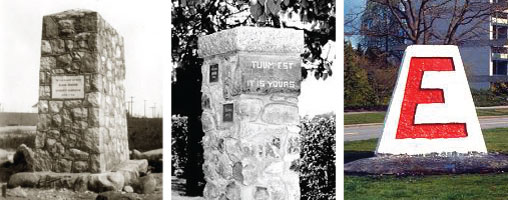

UBC and Tsinghua University express cultural identities through campus architecture. At UBC, the buildings and art along the main axis reflect cultural and social values. The Belkin Art Gallery (Figure 12) displays indigenous and modern art, helping the public connect with history and culture. The Engineering Cairn (Figure 13) is a long-standing student symbol representing campus traditions and collective identity. According to the Unsettling Settler Colonial Framework, this symbol shows how students shape campus identity through traditions and shared stories [2].

Tsinghua University highlights cultural heritage through traditional architecture. The Second School Gate (Figure 14) features red beams and decorated panels inspired by Qing Dynasty architectural styles. According to the Palladio Virtuel Theory, this design links the university’s past with its academic future through symbolic architectural elements [5]. The Grand Auditorium at Tsinghua displays classic wood carvings and traditional designs, reflecting cultural pride and academic history [7]. Its design and decorations show Tsinghua’s commitment to preserving and celebrating historical and cultural legacies.

Figure 14: The Second Gate of Tsinghua

4. Discussion and implications

The main axis designs of UBC and Tsinghua University provide compelling examples of how architecture can transcend mere functionality, becoming a symbol of cultural expression and environmental responsibility. At UBC, the architectural design emphasizes cultural diversity, environmental sustainability, and social inclusivity. The campus layout actively reflects the university’s commitment to community engagement, environmental stewardship, and the celebration of indigenous cultures. By integrating traditional cultural elements with modern eco-friendly technologies, UBC has created an open and forward-looking campus.

In contrast, Tsinghua University’s main axis design highlights historical heritage and cultural symbolism. By blending the essence of traditional Chinese architecture with garden design, Tsinghua’s main axis serves as a reminder of its historical and cultural roots. This approach underscores a deep respect for cultural preservation while reasserting its cultural identity in the context of globalization.

Future campus architectural design should balance cultural preservation with environmental responsibility. Designs should prioritize not only aesthetic and historical continuity but also respond to global environmental challenges by creating spaces that are socially and ecologically responsible. The main axis designs of UBC and Tsinghua University serve as exemplary models for multicultural expression and cultural heritage preservation, offering valuable design inspiration for future campus planning.

5. Conclusion

This paper has explored the comparative architectural strategies of UBC and Tsinghua University, focusing on the spatial, cultural, and ecological roles of their main axes. The analysis demonstrates that UBC’s campus planning prioritizes multicultural representation, sustainable design, and community inclusivity. It integrates modernist forms with Indigenous symbolism and cutting-edge environmental technology to create a campus that fosters cultural dialogue and ecological responsibility. Conversely, Tsinghua University’s axis-centered design draws on traditional Chinese garden principles, historical continuity, and Confucian spatial order to emphasize national heritage and academic dignity.

The comparative analysis of cultural symbolism, social interaction, sustainability, and identity (Sections 3.1–3.4) reveals key differences and similarities. UBC's use of transparent materials, student-centered hubs, and Indigenous installations aligns with its decolonial and environmentally conscious vision. Tsinghua’s use of axial symmetry, traditional motifs, and classical garden landscapes reflects a reverence for cultural order and intellectual tradition. Yet, both universities succeed in creating campus environments where built form resonates with larger societal narratives—be it post-colonial healing or civilizational continuity.

However, this study is not without limitations. It primarily analyzes two campuses from a qualitative and interpretive lens. Future research could incorporate more comparative case studies from other global universities and use quantitative tools like spatial mapping, user behavior analysis, or environmental performance metrics to enrich the findings. Additionally, incorporating more localized voices—such as student perspectives or Indigenous community input—would further ground the cultural analysis.

Looking ahead, future research on campus design should explore how universities can reconcile heritage with innovation. In a time of climate change and cultural globalization, main axis designs can serve as critical infrastructures for embedding sustainability, history, and inclusivity into the daily experience of academic life.

References

[1]. Eisenman, Peter, and Matt Roman Hofer. (2012). Palladio Virtuel. New Haven: Yale University Press.

[2]. Tuck, Eve, and K. Wayne Yang. (2022). Decolonization is Not a Metaphor. Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society, 1(1): 1-40.

[3]. Walter C. Koerner Library, accessed December 18, 2024, https: //www.library.ubc.ca/archives/bldgs/koernerlibr.htm.

[4]. Jun Wang. (2015). The Cultural Landscape of Tsinghua University: Tradition and Modernity Beijing: Tsinghua University Press, 13.

[5]. Peter Eisenman and Matt Roman Hofer. (2012). Palladio Virtuel. New Haven: Yale University Press, Preface.

[6]. Nest Catering & Conferences. “Nest Catering and Conferences - UBC.” June 23, 2023, https: //www.nestcatering.com/

[7]. Liu, Yishi. (2014). Building Guastavino Dome in China: A Historical Survey of the Dome of the Auditorium at Tsinghua University. Frontiers of Architectural Research, 3(2): 121–40.

[8]. Centre for Interactive Research on Sustainability (CIRS), accessed December 19, 2024, https: //www.library.ubc.ca/archives/bldgs/CIRS.html.

[9]. Jian Shen, Shubo Deng, and Jing Wu. (2021). Identifying Pollution Sources in Surface Water Using a Fluorescence Fingerprint Technique in an Analytical Chemistry Laboratory Experiment for Advanced Undergraduates. Journal of Chemical Education, 99(2): 932–40.

Cite this article

Ren,X. (2025). A Comparison of the Main Axis Architectural Design of the University of British Columbia and Tsinghua University: Cultural and Environmental Perspectives. Communications in Humanities Research,72,49-59.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of ICADSS 2025 Symposium: Art, Identity, and Society: Interdisciplinary Dialogues

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Eisenman, Peter, and Matt Roman Hofer. (2012). Palladio Virtuel. New Haven: Yale University Press.

[2]. Tuck, Eve, and K. Wayne Yang. (2022). Decolonization is Not a Metaphor. Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society, 1(1): 1-40.

[3]. Walter C. Koerner Library, accessed December 18, 2024, https: //www.library.ubc.ca/archives/bldgs/koernerlibr.htm.

[4]. Jun Wang. (2015). The Cultural Landscape of Tsinghua University: Tradition and Modernity Beijing: Tsinghua University Press, 13.

[5]. Peter Eisenman and Matt Roman Hofer. (2012). Palladio Virtuel. New Haven: Yale University Press, Preface.

[6]. Nest Catering & Conferences. “Nest Catering and Conferences - UBC.” June 23, 2023, https: //www.nestcatering.com/

[7]. Liu, Yishi. (2014). Building Guastavino Dome in China: A Historical Survey of the Dome of the Auditorium at Tsinghua University. Frontiers of Architectural Research, 3(2): 121–40.

[8]. Centre for Interactive Research on Sustainability (CIRS), accessed December 19, 2024, https: //www.library.ubc.ca/archives/bldgs/CIRS.html.

[9]. Jian Shen, Shubo Deng, and Jing Wu. (2021). Identifying Pollution Sources in Surface Water Using a Fluorescence Fingerprint Technique in an Analytical Chemistry Laboratory Experiment for Advanced Undergraduates. Journal of Chemical Education, 99(2): 932–40.