1. Introduction

With the rise of China’s comprehensive national strength and international influence, Chinese culture is steadily going global, and international Chinese language education has become an important part of the national strategy of “going out.” Against this backdrop, classical Chinese poetry—an important vehicle of Chinese culture that embodies profound philosophical thought, aesthetic sensibilities, and national spirit—has become a key component of international Chinese teaching. At present, international Chinese education has shifted from a focus on basic language skills to an emphasis on both linguistic competence and cultural literacy. As one of the core elements of intermediate and advanced Chinese instruction, the teaching of classical poetry plays an irreplaceable role in enhancing learners’ cultural understanding, intercultural communicative competence, and humanistic literacy.

However, numerous challenges arise in actual teaching. International students often report that the language of classical poetry is obscure and difficult, that cultural backgrounds create barriers, and that aesthetic experiences differ, leading to low interest, comprehension difficulties, widespread fear of difficulty, and even resistance. Such negative attitudes directly affect teaching outcomes and the effective dissemination of Chinese culture. Previous research has mostly focused on teaching methods, textbook compilation, and teacher qualifications, while paying relatively little systematic attention to the learners themselves—the attitudes of international students. Learner attitudes are a key factor influencing motivation, engagement, and ultimate outcomes. Therefore, investigating international students’ genuine attitudes toward classical poetry, the factors shaping those attitudes, and their patterns of change has urgent theoretical and practical significance for optimizing teaching strategies, improving instructional effectiveness, and promoting the deeper dissemination of Chinese culture.

2. Literature review

2.1. What content should be selected for teaching classical poetry to international students

Concerning the question of what content should be selected for teaching classical poetry to international students, Xiaonan Zhang [1] argues that foreign students’ learning of classical Chinese poetry focuses more on gaining awareness and general knowledge. Therefore, teaching should emphasize cultivating students’ literary appreciation ability by selecting accessible and high-quality works written by important and well-known poets. Huimin Gao [2], Yanli Feng [3], Yimo Zhao [4], and Wenwen Wei [5] share similar views, believing that in the early stages the selections should be simple and straightforward in content, short and concise in form, and easy to memorize. For example, in choosing works by Bai Li, Yanli Feng [3] suggests selecting relatively simple and widely celebrated poems for teaching. Huimin Gao [2] further notes that selections should have both a progressive sequence and a systematic structure. Wenwen Wei [5] also emphasizes the need to choose works with strong storytelling, vivid imagery, and the capacity to evoke emotional resonance among students. Yimo Zhao [4] proposes that works should be representative, targeted, and practical, capable of reflecting the characteristics of the era, prevailing ideas, lifestyles, and customs. Students should be able to acquire cultural information from the works while also benefiting in pronunciation, vocabulary enrichment, and grammatical correctness, thereby gaining greater knowledge of Chinese culture and mastering fundamental concepts. Shengli Long [6] further suggests that classical poetry can be taught in conjunction with musical adaptations of poems.

2.2. International students’ attitudes toward classical poetry

Regarding the question of international students’ attitudes after being exposed to classical poetry teaching, Xiaonan Zhang [1] points out that due to limitations in Chinese proficiency, differences in cultural background, the lack of immersion in Chinese cultural heritage, as well as the absence of a natural sense for the language and an ability to recognize the “beauty” of Chinese, foreign students generally find it difficult to appreciate the subtleties of Chinese classical poetry. They often experience comprehension difficulties and a sense of estrangement. More specifically, what students find most difficult to understand is the poet’s creative attitude, followed by imagery, metaphor, and allusions, then grammar, and finally the teacher’s method of explanation. Therefore, teachers need to use plain and accessible language in their explanations. Ruqi Qian [7] agrees with this view, arguing that many students lose interest in classical poetry because of difficulties in understanding word meanings and because teaching methods are often monotonous.

Wenhui Tu [8] and Lixuan Luo [9] both studied the characteristics of international students in learning and using Chinese. On this basis, Wenhui Tu [8] suggests that although international students initially lack a natural sense of the language and the ability to discern its “beauty,” through long-term instructional practice, they will develop greater understanding of and interest in Chinese literature and history. Lixuan Luo [9] observes that after studying classical poetry, students can generally grasp the content and meaning, but errors or mistakes still occur in actual application.

Ruqi Qian [7] and Yilin Li [10] both point out that when learning classical poetry, students encounter difficulties in pronunciation, semantics, grasp of emotions, understanding of the creative background, and appreciation of artistic conception, thus their motivation to learn requires improvement.

Since the HSK (Chinese Proficiency Test) rarely involves classical poetry, many international students prioritize the study of basic language knowledge instead. Hehong Gong [11] and Yilin Li [10] agree on this point and further note that because classical poetry is disconnected from modern society and lacks practicality, students tend to undervalue its teaching.

3. Research design

3.1. Research participants

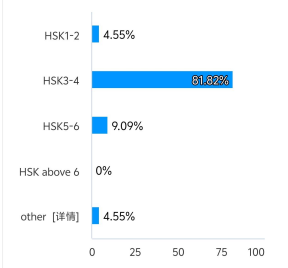

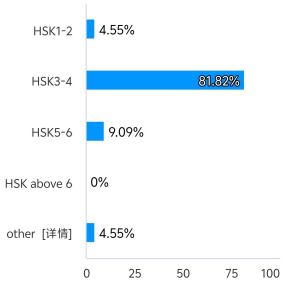

This study takes international students from the College of International Cultural Education at Northeast Agricultural University as its participants, covering groups with different levels of Chinese proficiency (beginner, intermediate, advanced), various nationalities, and different lengths of study. Using a random sampling method, questionnaires were distributed, and 22 valid responses were collected, yielding a 100% valid response rate. The basic characteristics of the sample are as follows: in terms of Chinese proficiency, beginners accounted for 9.1%, intermediate learners 81.82%, and advanced learners 9.09%. Regarding study duration, 18.18% had studied for less than one year, 13.64% for one to two years, and 68.18% for more than two years. The sample included students from Asia, Europe, and Africa, ensuring both diversity and representativeness.

3.2. Research instruments

The study employed a self-designed questionnaire titled Survey on International Students’ Learning of Classical Chinese Poetry. The questionnaire was developed based on key issues identified in the research background and literature review, and it primarily included the following dimensions:

• International students’ learning attitudes toward classical Chinese poetry (e.g., level of interest, willingness to learn).

• Difficulties encountered in learning classical Chinese poetry (e.g., language comprehension, cultural background, aesthetic experience).

• Key factors influencing international students’ learning attitudes toward classical Chinese poetry (e.g., teaching methods, teacher explanations, personal experiences).

3.3. Research methods

The study mainly adopted a questionnaire survey method. Electronic questionnaires were distributed through the Wenjuanxing (Questionnaire Star) platform to collect relevant data on international students’ learning of classical poetry. After data collection, SPSS 26.0 statistical software was used to conduct descriptive statistics (e.g., mean, standard deviation), difference analysis (e.g., t-test, ANOVA), and correlation analysis, in order to investigate the current situation, attitudes, and influencing factors of international students’ learning of classical Chinese poetry.

4. Analysis of international students’ learning of classical Chinese poetry

4.1. Cognitive dimension

4.1.1. Channels of exposure

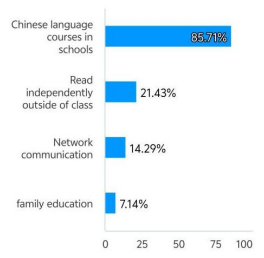

The vast majority of international students (85.71%) were first exposed to classical Chinese poetry through Chinese language courses at school. Others encountered it through the internet (14.29%) and extracurricular reading (21.43%). This indicates that classroom teaching remains the dominant channel for the dissemination of poetry, while the potential of modern online media is yet to be fully utilized.

4.1.2. Familiarity

The survey shows that only 9.09% of students reported being “very familiar” with certain classical poems, reflecting an overall low level of familiarity. Among the poets known, Bai Li was mentioned most frequently, which is closely related to the widespread circulation of his works and their frequent inclusion in textbooks. In contrast, familiarity with other poets such as Wei Wang and Haoran Meng was relatively low.

4.2. Learning attitudes

4.2.1. Level of interest

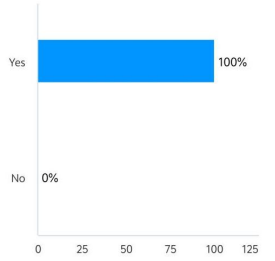

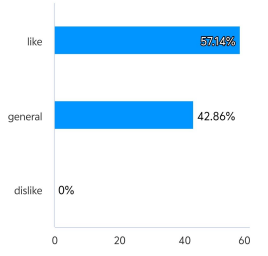

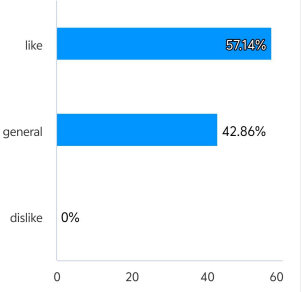

Among students who had not yet taken a classical poetry course, all expressed an interest in it. Among those who had taken relevant courses, about 57.14% indicated a certain degree of interest in learning classical poetry.

4.2.2. Language proficiency

Within the sample, 81.82% (18 students) had Chinese proficiency at HSK Level 3–4 (intermediate to upper-intermediate), and 68.18% (15 students) had studied in China for more than two years, giving them a basic foundation of cultural exposure.

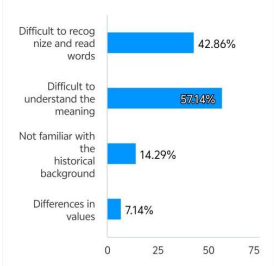

4.3. Learning difficulties

4.3.1. Language barriers

More than 57.14% of students identified vocabulary comprehension as the main obstacle. The large number of rare characters, words with different meanings in ancient and modern Chinese, and polysemy in classical poetry pose significant challenges. For example, the word kelian (可怜) often meant “lovely” in ancient poetry, which is very different from its modern meaning of “pitiful.”

4.3.2. Cultural barriers

Over 14.29% of students felt that a lack of understanding of China’s ancient historical and cultural background was a major obstacle in learning poetry. Without knowledge of ancient political systems, social customs, or religious beliefs, it is difficult to grasp the full meaning of poems. For instance, without understanding the imperial examination system, one cannot fully appreciate the exuberant joy expressed in Haoran Meng’s After Passing the Imperial Examination: “With the spring breeze in high spirits, the horse’s hooves fly; in a single day, I see all the flowers of Chang’an.”

4.3.3. Differences in values

Students’ native values differ from traditional Chinese values. Classical poetry emphasizes subtlety and the beauty of imagery, while some cultural contexts prefer directness and bold expression. This cultural aesthetic gap led about 7.14% of students to admit difficulty in appreciating the aesthetic connotations and values embedded in Chinese poetry.

4.4. Factors influencing learning

4.4.1. Personal factors

4.4.1.1. Chinese proficiency

Chinese proficiency is positively correlated with the learning of classical poetry. Learners with higher proficiency levels show clear advantages in vocabulary comprehension and grammatical analysis, resulting in greater understanding and acceptance. Approximately 81.82% of intermediate and advanced learners reported relatively easy comprehension.

4.4.1.2. Level of interest

57.14% of students explicitly stated that they “like” classical poetry, while 42.86% expressed a neutral attitude. The higher the level of interest, the stronger the students’ learning motivation.

4.4.2. Instructional factors

4.4.2.1. Teaching methods

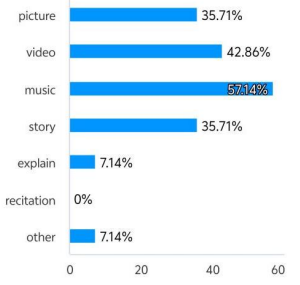

Most students felt that current teaching methods were monotonous, relying mainly on teacher lecturing with insufficient interaction and engagement. The traditional didactic approach neglects learners’ agency and practical needs, resulting in low motivation. The most preferred teaching forms identified by students were: music (57.14%), videos (42.86%), pictures (35.71%), stories (35.71%), and direct explanation (7.14%).

4.4.2.2. Textbook content

Some students reported that the difficulty level of selected poems in textbooks was not well balanced: some were too simple to meet their learning needs, while others were too difficult, exceeding their comprehension capacity. In addition, the cultural background of the poems was not explained in sufficient detail, hindering deeper learning.

4.4.2.3. Curriculum design

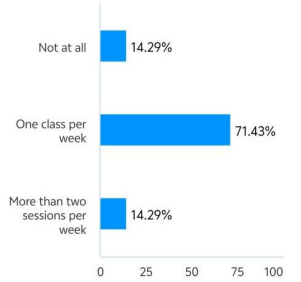

On the one hand, class hours were insufficient: 14.29% of students attended at least two classes per week, 71.43% only one class per week, and 14.29% had no relevant courses. On the other hand, the learning cycle was relatively long: 50% of students required at least one week to master a single poem, reflecting room for improvement in teaching efficiency.

4.4.3. Social and environmental factors

4.4.3.1. Cultural atmosphere

The extent to which Chinese culture is promoted in students’ environments significantly affects their exposure to and interest in classical poetry. In regions where Chinese culture is actively promoted, students had more opportunities to encounter poetry and showed greater enthusiasm for learning. Conversely, in environments with a weaker cultural atmosphere, students lacked external motivation to study poetry.

4.4.3.2. Exam orientation

Mainstream Chinese language proficiency exams such as the HSK place relatively little emphasis on classical poetry. As a result, many students perceived limited relevance of poetry study to exam performance, leading them to pay less attention to it.

5. Conclusion

5.1. Analysis of current learning attitudes

The survey results reveal that international students’ overall attitude toward classical Chinese poetry is at a moderate level, with a certain degree of interest. Questionnaire data indicate that 57.14% of those who had studied poetry explicitly stated they “like” it. Notably, among students at HSK Levels 5–6, this proportion rose to 75% (two students in the advanced-level sample), confirming Wenhui Tu’s [8] assertion that “the improvement of language ability promotes cultural identity.” However, a widespread sense of difficulty also exists among international students: 78.57% reported that they could only “partially understand” poetry, with 42.86% attributing this difficulty to “lexical comprehension.” This finding is consistent with the conclusions of Xiaonan Zhang [1], Wenhui Tu [8], and other scholars. It can thus be inferred that students with higher Chinese proficiency and longer learning experience tend to have a more positive attitude, suggesting that as their language skills improve and cultural understanding deepens, their receptiveness to classical poetry increases. Nevertheless, some students develop resistance due to learning difficulties, which directly affects both their learning outcomes and the broader effectiveness of cultural dissemination.

5.2. Causes of learning difficulties

Factors affecting international students’ motivation to learn classical Chinese poetry exist primarily at three levels: language, culture, and teaching. First, the language dimension: insufficient Chinese proficiency. Unlike modern Chinese, the particularities of Classical Chinese constitute an objective barrier. Words with different meanings in ancient and modern Chinese, such as kelian (可怜), as well as the numerous historical allusions in Nian Nu Jiao: Chibi Huaigu, create significant difficulties for students’ comprehension. Existing questionnaire data indicate that as students’ Chinese proficiency improves, their willingness to learn poetry correspondingly increases. Second, the cultural dimension: significant cultural barriers. Different cultural backgrounds result in a lack of resonance with the cultural connotations of poetry. Compared with students from the Asian cultural sphere, students from Europe and the United States face greater difficulties in understanding classical Chinese poetry. To address this, it is recommended that introductory poetry courses use simple, accessible works to reduce feelings of difficulty and increase learning interest. Poems with themes of homesickness, such as “I lift my head to gaze at the bright moon, and lower it to think of home,” can evoke emotional resonance and facilitate comprehension. Third, the teaching dimension: traditional teaching methods. Some teachers still employ lecture-based instruction, which does not fully consider the learning characteristics and needs of international students. This necessitates reform in both teaching content and teaching methods. The interaction of these factors results in students having a limited and unsatisfactory learning experience with classical poetry.

5.3. Implications for teaching content selection

Students’ preferences regarding teaching content provide clear guidance for practice. Instruction should follow a principle of progression from simple to complex, with material selection tailored to students’ Chinese proficiency. For beginner-level learners (HSK 3–4): Short, concise, and easily understandable poems with vivid imagery (e.g., Quiet Night Thoughts, Spring Morning) should be prioritized. Multimedia resources such as animations and songs may be used to support teaching. For advanced-level learners (HSK 5–6): Longer narrative works (e.g., Song of the Pipa) may be introduced, supplemented by documentaries to reconstruct historical and cultural contexts. Cross-cultural comparisons can also be employed—for example, comparing Bai Li’s Drinking Alone Under the Moon with Persian poet Rumi’s poems on solitude—to foster intercultural understanding and reconcile differences in values. In addition, integrating poetic songs (e.g., May We All Be Blessed with Longevity) can effectively stimulate interest and aid in memorizing key images (such as the “bright moon”). Care should be taken, however, to select songs of moderate difficulty that align with students’ needs, avoiding works laden with obscure vocabulary (e.g., Li Sao). These perspectives resonate with the findings of Shengli Long [6] and Wenwen Wei [5].

5.4. Practical significance of influencing factors

The factors influencing students’ attitudes provide a basis for optimizing teaching strategies. On the one hand, strengthening language training is essential. For the 57.14% of students who reported difficulty with word meanings, targeted practice on high-frequency words with classical-modern differences is recommended. For example, kelian (可怜) in Classical Chinese often meant “lovely,” while qizi (妻子) referred to “wife and children” rather than simply “wife.” On the other hand, innovating teaching methods through multimodal resources is equally important. Teachers should employ images, videos, and music to create cultural contexts and increase interaction. For example, playing musical adaptations of Spring Morning can spark interest, while animated ink-painting videos of River Snow can deepen understanding of poetic imagery, such as the “lone boat and old man in a bamboo hat and cape.” Furthermore, encouraging participation in cultural activities can enhance intercultural exchange and reshape students’ attitudes toward poetry. For instance, during the Mid-Autumn Festival, students might engage in mooncake-making activities while reciting Su Shi’s Prelude to Water Melody: When Will the Moon Be Clear and Bright, thereby strengthening both cultural experience and emotional engagement.

References

[1]. Zhang, X. (2012). An analysis of teaching Chinese ancient poetry courses for international students. Journal of Inner Mongolia Normal University (Educational Science Edition), (1), 101–105.

[2]. Gao, H. (2002). A discussion on teaching ancient poetry to international students. Journal of Huaqiao University (Philosophy and Social Sciences Edition), (4), 87–90.

[3]. Feng, Y. (2012). Teaching Li Bai’s poetry in teaching Chinese as a foreign language (Master’s thesis). Lanzhou University.

[4]. Zhao, Y. (2020). Research on teaching Chinese classical poetry in CFL classrooms under a cross-cultural background. Journal of Jilin Institute of Education, (1), 95–98.

[5]. Wei, W. (2023). Research on teaching ancient Chinese poetry under multimodal theory: A case study of Turkmen students (Master’s thesis). Shaanxi University of Technology.

[6]. Long, S. (2014). An exploration of applying ancient poetry songs in CFL teaching (Master’s thesis). Sichuan Normal University.

[7]. Qian, R. (2010). A preliminary study on teaching ancient poetry in intermediate and advanced stages of CFL (Master’s thesis). Zhejiang University.

[8]. Tu, W. (2004). On the particularity of teaching ancient literature in the advanced stage of CFL. Journal of Huaqiao University (Philosophy and Social Sciences Edition), (4), 91–96.

[9]. Luo, L. (2016). A survey on the learning of Chinese ancient poetry by Malagasy students: A case study of Jiangxi Normal University (Master’s thesis). Jiangxi Normal University.

[10]. Li, Y. (2022). A study on teaching ancient poetry to intermediate and advanced international students: A case study of three universities in Henan (Master’s thesis). Zhengzhou University.

[11]. Gong, H. (2016). Research on teaching ancient poetry from the perspective of CFL teaching (Master’s thesis). Harbin Normal University.

Cite this article

Zeng,B. (2025). A Study on International Students’ Learning of Classical Chinese Poetry. Communications in Humanities Research,75,144-154.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of ICADSS 2025 Symposium: Consciousness and Cognition in Language Acquisition and Literary Interpretation

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Zhang, X. (2012). An analysis of teaching Chinese ancient poetry courses for international students. Journal of Inner Mongolia Normal University (Educational Science Edition), (1), 101–105.

[2]. Gao, H. (2002). A discussion on teaching ancient poetry to international students. Journal of Huaqiao University (Philosophy and Social Sciences Edition), (4), 87–90.

[3]. Feng, Y. (2012). Teaching Li Bai’s poetry in teaching Chinese as a foreign language (Master’s thesis). Lanzhou University.

[4]. Zhao, Y. (2020). Research on teaching Chinese classical poetry in CFL classrooms under a cross-cultural background. Journal of Jilin Institute of Education, (1), 95–98.

[5]. Wei, W. (2023). Research on teaching ancient Chinese poetry under multimodal theory: A case study of Turkmen students (Master’s thesis). Shaanxi University of Technology.

[6]. Long, S. (2014). An exploration of applying ancient poetry songs in CFL teaching (Master’s thesis). Sichuan Normal University.

[7]. Qian, R. (2010). A preliminary study on teaching ancient poetry in intermediate and advanced stages of CFL (Master’s thesis). Zhejiang University.

[8]. Tu, W. (2004). On the particularity of teaching ancient literature in the advanced stage of CFL. Journal of Huaqiao University (Philosophy and Social Sciences Edition), (4), 91–96.

[9]. Luo, L. (2016). A survey on the learning of Chinese ancient poetry by Malagasy students: A case study of Jiangxi Normal University (Master’s thesis). Jiangxi Normal University.

[10]. Li, Y. (2022). A study on teaching ancient poetry to intermediate and advanced international students: A case study of three universities in Henan (Master’s thesis). Zhengzhou University.

[11]. Gong, H. (2016). Research on teaching ancient poetry from the perspective of CFL teaching (Master’s thesis). Harbin Normal University.