1. Introduction

The existential construction (There be + NP + Locative) is a core sentence pattern in the English grammatical system. Through its unique structure of “expletive subject ‘there’ + predicate verb + post-verbal noun phrase,” it breaks the conventional English “Subject-Verb” word order, constructing a specific spatial cognitive framework for introducing focal information (the NP).

Research on the “There be” construction has long been relatively scarce, with previous studies mostly focusing on its syntactic generation mechanisms or functional exploration, examining its constructional features [1], referentiality changes [2], or analyzing its information structure function from a functional linguistics perspective [3]. However, these studies have largely overlooked a fundamental question: what is the conceptual essence behind this special syntactic form? Existing syntactic or functional explanations fail to fully reveal its underlying cognitive motivation.

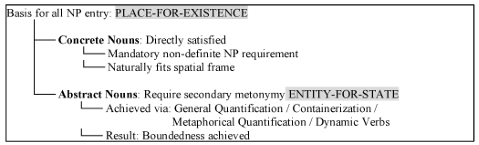

To address this research gap, this study, grounded in Grammatical Metonymy Theory [4], proposes that the generation of the English existential construction is rooted in a two-tiered metonymic operation: the core metonymy PLACE-FOR-EXISTENCE maps an existential event onto a spatial frame “there”, forming the basis for the entry of all NPs; whereas abstract nouns, lacking inherent spatial attributes, require the secondary metonymy ENTITY-FOR-STATE, achieved through quantification, containerization, and other means to realize “reification.” To validate this model, this paper employs corpus analysis to examine the definiteness features of NPs and the reification strategies for abstract nouns, combines diachronic evidence to trace the grammaticalization path of “there,” and reveals differences in cognitive strategies across languages through a Chinese-English contrast. The research aims to provide an in-depth cognitive explanation for the English existential construction.

2. Theoretical framework

2.1. Core conceptual definitions

To clarify the nature of the “There be” construction, we need to define three core theoretical concepts supporting this study. First, Grammatical Metonymy refers to the metonymic mapping from a “source” concept to a “target” concept within the conceptual structure [4], realized through adjustments in grammatical form. This mapping provides the conceptual motivation for unconventional yet acceptable syntactic collocations. Second, the core of Cognitive Grammar is that syntax is the symbolic representation of fundamental human cognitive experiences and modes of conceptualization [5]. Humans are cognitively predisposed to construe abstract, intangible concepts as concrete, quantifiable entities. This cognitive capacity for “reification” provides the fundamental possibility for abstract nouns to enter the existential construction like concrete objects. Finally, Figure-Ground Organization [6] reveals how language regulates cognitive salience through grammatical means. In a perceptual scene, the “Figure” is typically the moving, smaller, conceptually more accessible entity occupying the cognitive focus, while the “Ground” is the relatively stationary, larger entity providing spatial or temporal reference for the “Figure”. This theory is crucial for explaining why the “There be” construction adopts the special word order of “expletive subject + post-verbal noun.”

2.2. Metonymic operation model

2.2.1. Core metonymy: PLACE-FOR-EXISTENCE

The most fundamental cognitive basis of the “There be” construction is using the concept of “spatial location” as the source domain to refer to the target domain of an “existence event.” This core metonymic operation is a prerequisite for any noun to enter this construction. Its specific connotation is shown in Table 1:

|

Dimension |

Content |

Theoretical Support |

|

Cognitive Essence |

Using a spatial container (there) to refer to an existence event, forming the “SPACE IS EXISTENCE.” |

Langacker’ views on spatial conceptualization [5]. |

|

Syntactic Manifestation |

•Mandatory presence of expletive subject “there”• NP is mostly non-definite |

(Delete the first sentence of the original text)Wang Yin explains this that definite subject presuppose existence and violate the construction’s function to introduce new subjects [7]. |

|

Universality |

Applicable to all existents (concrete/abstract) |

|

2.2.2. Secondary metonymy: ENTITY-FOR-STATE

For abstract nouns lacking physical form, they require an auxiliary metonymic mechanism, namely the secondary metonymy ENTITY-FOR-STATE. This process is key to achieving the “reification” of the NP. The specific connotation is shown in Table 2:

|

Dimension |

Content |

Theoretical Support |

|

Cognitive Essence |

Construing an abstract state (e.g., hope) as a spatially bounded entity (e.g., a ray of hope) through ontological metaphor. |

Langacker on “reification of abstract concepts” [5]; Wei Zaijiang proposes that the process of reification for emotional categories involves making the unbounded bounded. This process relies on the cognitive mechanism of grammatical metonymy [8]. |

|

Syntactic Manifestation |

Mostly requires mandatory quantificational modification, metaphorical containers, or dynamic verbs. |

BNC corpus statistics shows admission rate of unquantified abstract nouns < 0.02% [7]. |

|

Universality |

Only abstract nouns require this metonymy. |

|

Synthesizing the above analysis, we construct the following metonymic operation model for the “There be” existential construction (Figure 1):

3. Empirical analysis: corpus evidence for the metonymic operation model

This section provides empirical validation for the proposed metonymic operation model through corpus analysis and diachronic investigation, specifically exploring noun entry conditions, the grammaticalized nature of there, and cognitive differences in English and Chinese realization.

3.1. All nouns: non-definite entry condition

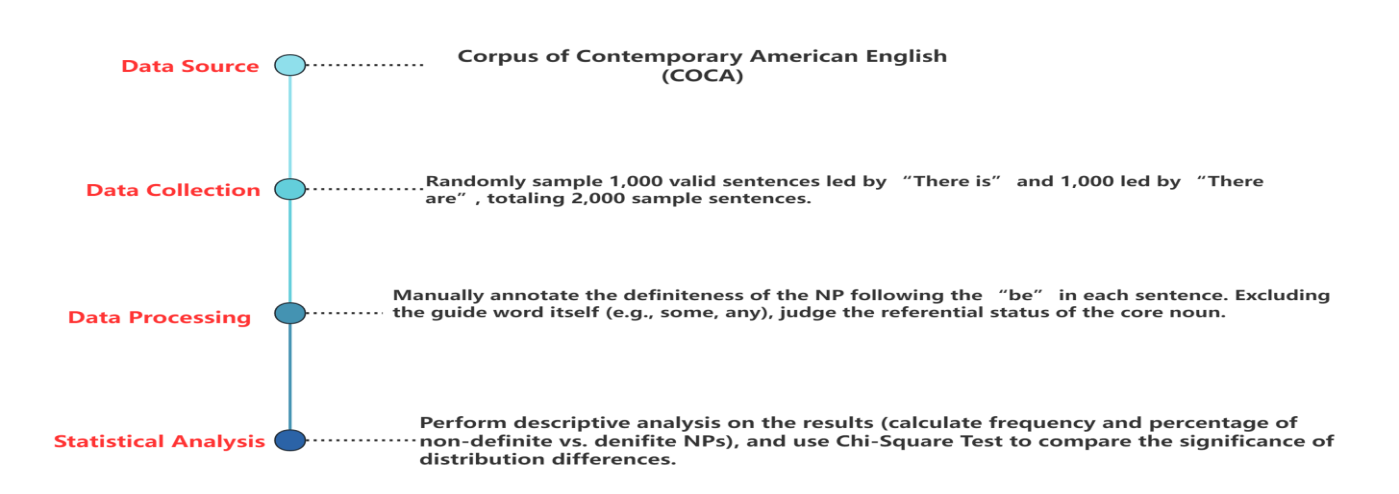

The function of the existential construction is to assert the appearance of a new entity. Definite nouns presuppose the entity's existence, leading to “existential redundancy” [7]. Therefore, concrete nouns tend to enter the construction in non-definite forms. To verify this view, this study designed the following scheme, as shown in Figure 2:

The results showed that non-definite NPs (e.g., a book, three cats, some students) accounted for 1,942 instances, or 97.1% of the total. Definite NPs (e.g., the problem, his car) accounted for only 58 instances, or 2.9%. The few instances of definite NPs all occurred in special pragmatic contexts, such as indicating “reminder, discovery” (“There is the tax, of course.”) or used in enumeration (“First, there’s the issue of cost. Second, there’s the problem of time...”). Their function deviates from the core function of “introducing a brand-new entity” of the construction, instead signaling a known entity that becomes relevant or visible in the immediate context. Chi-square test analysis indicated an extremely significant difference in the distribution between non-specific and specific NPs (χ² = 1772.728, df = 1, p < 0.001), confirming the mandatory requirement of the existential construction for non-specific noun phrases.

3.2. Abstract nouns: mandatory nature of reification

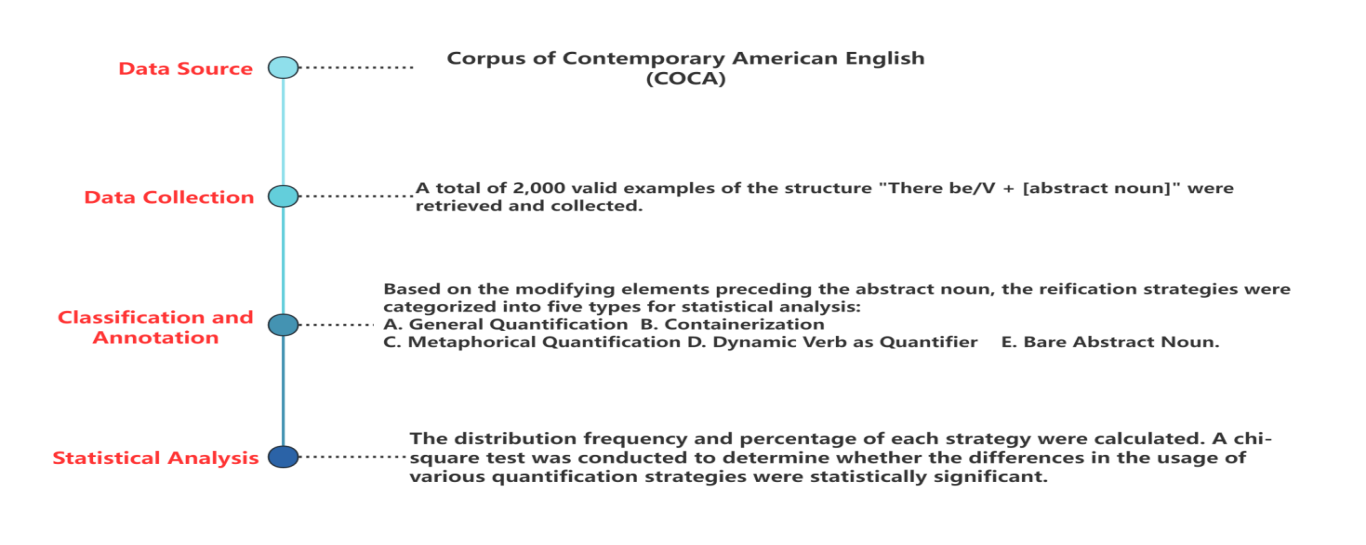

Abstract nouns lack inherent spatial entity status and cannot directly integrate into the PLACE-FOR-EXISTENCE cognitive frame. Their entry into the construction requires various quantification or reification means to reshape them into a “bounded”,countable virtual entity [9]. Existing corpus evidence shows that the admission rate of unquantified abstract nouns in the BNC is <0.02%, and the admission rate of abstract nouns is positively correlated with reification means [7]. To verify this view, this paper designed the following research scheme, as shown in Figure 3:

A statistical analysis of 2,000 valid examples of “There be/V + abstract noun” from the COCA corpus, classified by reification means, yielded the distribution proportions shown in Table 3:

|

Reification Means Category |

Judgment Criteria |

Count |

Percentage |

|

General Quantification |

Whether the NP is preceded by determiners or phrases indicating indefinite quantity, such as some, any, no, little. |

1,142 |

57.1% |

|

B. Containerization |

Whether the NP is an “a/an + N1 + of + (Det) + N2 (abstract)” structure, where N1 is a noun denoting container, scope, or perception (e.g., sense, feeling, air). |

378 |

18.9% |

|

C. Metaphorical Quantification |

Whether the NP is an “a/an + N1 + of + (Det) + N2 (abstract)” structure, where N1 is a metaphorical noun denoting concrete things like light, sound, trace (e.g., ray, glimmer, trace). |

248 |

12.4% |

|

D. Dynamic Verb (as Quantifier) |

Whether the verb in the sentence is an intransitive verb other than be that denotes “appearing, happening, persisting, existing” (e.g., arise, emerge, develop). |

212 |

10.6% |

|

E. Bare Abstract Noun |

Whether the NP is a “bare” abstract noun. |

20 |

1.0% |

Chi-square test results showed that the distribution differences between categories were statistically significant (χ² = 1874.3, df = 4, p < 0.001). Among them, bare abstract nouns without any reification means (Category E) had an extremely low admission rate (only 1.0%), and in the very few examples, their acceptability was often strongly constrained by context or sounded unnatural. Over 99% of abstract nouns achieved “”boundedness” through one of the means in categories A-D, with “general Quantification” (Category A, 57.1%) being the most common means, followed by “Containerization” (Category B, 18.9%), “Metaphorical Quantification” (Category C, 12.4%), and “Dynamic Verbs” (Category D, 10.6%). These results strongly demonstrate that the secondary metonymy ENTITY-FOR-STATE is not only necessary but also syntactically mandatory for abstract nouns to enter the “There be” construction.

3.3. Diachronic evidence: metonymic desemanticization of expletive “there”

Traugott has identified the following diachronic evidence [10]:

• Middle English: There sat a knight (“there” denotes a real location);

• Modern English: There is a problem (“there” grammaticalized into an existential marker).

This study, consulting the COHA and OED corpora, found the following examples:

• Old English:“Þær wæs symbla cyst” → “There was a great feast” – Old English epic Beowulf

“Þær” (there) had a clear demonstrative pronoun and locative adverb function, here pointing to a specific, previously mentioned location– Heorot hall.

• Early Modern English: “There is a tide in the affairs of men” – Shakespeare, Julius Caesar

“There” begins to be used to introduce an unknown entity; its locative meaning starts to generalize and blur. Here, the function of “there” is closer to introducing an existing phenomenon or truth.

• Modern English:“There's no place I'd rather be right now than in your room.” – J.D. Salinger, The Catcher in the Rye

There is fully grammaticalized into a syntactic function word (expletive subject).

Etymological and diachronic corpus examination clearly shows the grammaticalization path of “there” from a contentful locative adverb to a functional existential marker. This process is the result of the gradual bleaching of its spatial meaning via PLACE-FOR-EXISTENCE).

3.4. Contrast of realization and cognitive strategies

By comparing classic existential sentences from the COCA (English) and BCC (Chinese) corpora, the following differences in the realization means and cognitive strategies of existential constructions between English and Chinese can be observed, as shown in Table 4:

|

Comparison Dimension |

English Existential Construction |

Chinese Existential Sentence |

Analysis |

|

Structure |

There + V + NP + Loc. |

Loc. + V + NP |

The English construction adjusts cognitive salience through focus finalization, making the NP the “Figure” (focus of attention) and the spatial frame built by “there” the “Ground” (reference), conforming to Figure-Ground Theory [6]. Chinese uses a concrete or generalized location word to directly serve as the syntactic subject. The construction unfolds in the natural order of "Ground-Action-Figure," representing a direct lexicalized presentation. |

|

Core Verb |

Highly restricted, primarily “be” “exist” and a few presentation verbs like “appear” “emerge” “remain” |

Extremely rich, can be subdivided by meaning:Existence: 桌上放着一本书。(A book is lying on the table.) Appearance: 远处来了一个人。(A person came from afar.)Disappearance: 村里死了一头牛。(A cow died in the village.) |

The verb function in the English existential construction is highly grammaticalized; the singularity of the verb form aims not to distract attention from the focal NP. The verbs in Chinese existential sentences carry significant lexical and semantic load, containing more information. |

|

Concrete Noun Example |

There is a book on the table. |

桌上有一本书。(On table has one book.) |

English: “there” as formal subject constructs the “Ground”; “a book” as logical subject is postposed and focalized. The prepositional phrase on the table is supplementary Ground information.Chinese: “桌上” (on the table) is the syntactic subject and cognitive “Ground”; “一本书” (one book) is the object and cognitive “Figure”. Word order naturally realizes the cognitive flow from “Ground” to “Figure”. |

|

Abstract Noun Example |

There is some hope. |

(他)心中有一线希望。(He) in-heart has one-thread hope.) |

English: there creates an abstract “mental space” frame; some reifies the abstract concept “hope,” making it a “Figure” that can be focused on.Chinese: Expressing abstract existence requires lexicalizing an abstract container, like “心中” (in the heart), “世上” (in the world), to serve as the subject (Ground), then using a measure word like “一线” (a thread of) to reify the abstract noun into a “Figure”. |

|

Metonymy Mechanism |

Grammaticalized Metonymy |

Lexicalized Metonymy |

English adjusts cognitive salience through grammaticalized means, while Chinese relies more on lexical means to directly present the scene. |

The English existential construction is essentially a highly grammaticalized information structure construction. Its primary function is to use the syntactic means of “focus finalization” to make spatial information (jointly borne by “there” and the locative phrase), which should serve as the “Ground”, the syntactic starting point, while reserving the core focus position for the existent (NP). In contrast, the Chinese existential sentence (Loc. + V + NP) more directly reflects the human order of perceiving space: first locate (Ground), then observe the process (Action), and finally focus on the object (Figure). Cognitive salience is achieved through relatively natural word order and lexical choice. Therefore, Chinese verbs can retain their rich semantics, whereas English sacrifices verb diversity for the function of focus regulation.

4. Discussion and conclusion

This study, by constructing a metonymic operation model and analyzing extensive corpus data, systematically argues for the cognitive metonymic motivation of the English “There be” existential construction. Its new findings can be summarized in following points:

Firstly, it has proposed and validated an original two-tier metonymic model (PLACE-FOR-EXISTENCE and ENTITY-FOR-STATE), offering a more integrated account of the construction's cognitive motivation. Secondly, it has provided substantial corpus-based evidence that strongly confirms the canonical requirement for non-definite NPs. Beyond validating prior theories [7], it has developed a more refined classification of reification mechanisms for abstract nouns and presented their empirical distribution. A unique theoretical insight emerging from this model is the novel conceptualization of the grammaticalization of “here” as a specific case of metonymic desemanticization, linking syntactic change directly to cognitive processes. Lastly, the cross-linguistic analysis has offered an updated perspective, characterizing the English-Chinese difference as a fundamental contrast between grammaticalized and lexicalized strategies for metonymy, moving beyond traditional syntactic comparison. Limitations of the study include the need for deeper examination of the context dependency of abstract noun reification means; future research could further expand the scope of cross-linguistic comparison or employ neurolinguistic methods to verify the cognitive reality of the metonymic operations.

In conclusion, this study ultimately demonstrates that grammar is not a set of cold formal rules but a symbolic system rooted in human embodied cognition. The essence of the English existential construction is the grammaticalized product of metonymic cognition.

References

[1]. Li, B., Yang, K., & Wen, X. (2023). A Constructionalization Analysis of the There-Existential Construction and the There-Deictic Construction. Foreign Language Research (Collection), (1), 72-88.

[2]. Li, X., & Liu, Z. G. (2023). A Study on Referentiality Change and the Subjective Meaning of the There-Construction. Foreign Language Teaching and Research, 55(2), 189-201, 319.

[3]. Xu, Y. H. (2019). A Study on the Function of the There-Existential Construction in Political Discourse from a Critical Cognitive Perspective (Master’s thesis). Zhejiang University of Finance and Economics.

[4]. Panther, K.-U., & Thornburg, L. L. (2009). Metonymy and Metaphor in Grammar. John Benjamins.

[5]. Langacker, R. W. (2008). Cognitive Grammar: A Basic Introduction. Oxford University Press.

[6]. Talmy, L. (2000). Toward a Cognitive Semantics (Vol. 1). MIT Press.

[7]. Wang, Y. (2019). An Analysis of the There-Be Existential Construction Based on Russell’s Theory of Descriptions: Can 'Existence’ Be a Predicate? Foreign Language Research, (1), 1-6.

[8]. Wei, Z. J. (2021). The Cognitive Metonymic Motivation of Grammatical Constructions: A Case Study of the “Verb-Object + Object” Construction. Foreign Languages in China, 18(3), 24-30.

[9]. Wei, Z. J. (2022). An Embodied-Cognitive Perspective on the Boundedness of English Nouns. Foreign Languages in China, 19(6), 38-43, 51.

[10]. Traugott, E. C. (2004). Exaptation and Grammaticalization. Linguistic Society of America Annual Meeting.

Cite this article

Wang,H. (2025). The Cognitive Metonymic Motivation of the English “There be” Existential Construction. Communications in Humanities Research,84,16-23.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Interdisciplinary Humanities and Communication Studies

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Li, B., Yang, K., & Wen, X. (2023). A Constructionalization Analysis of the There-Existential Construction and the There-Deictic Construction. Foreign Language Research (Collection), (1), 72-88.

[2]. Li, X., & Liu, Z. G. (2023). A Study on Referentiality Change and the Subjective Meaning of the There-Construction. Foreign Language Teaching and Research, 55(2), 189-201, 319.

[3]. Xu, Y. H. (2019). A Study on the Function of the There-Existential Construction in Political Discourse from a Critical Cognitive Perspective (Master’s thesis). Zhejiang University of Finance and Economics.

[4]. Panther, K.-U., & Thornburg, L. L. (2009). Metonymy and Metaphor in Grammar. John Benjamins.

[5]. Langacker, R. W. (2008). Cognitive Grammar: A Basic Introduction. Oxford University Press.

[6]. Talmy, L. (2000). Toward a Cognitive Semantics (Vol. 1). MIT Press.

[7]. Wang, Y. (2019). An Analysis of the There-Be Existential Construction Based on Russell’s Theory of Descriptions: Can 'Existence’ Be a Predicate? Foreign Language Research, (1), 1-6.

[8]. Wei, Z. J. (2021). The Cognitive Metonymic Motivation of Grammatical Constructions: A Case Study of the “Verb-Object + Object” Construction. Foreign Languages in China, 18(3), 24-30.

[9]. Wei, Z. J. (2022). An Embodied-Cognitive Perspective on the Boundedness of English Nouns. Foreign Languages in China, 19(6), 38-43, 51.

[10]. Traugott, E. C. (2004). Exaptation and Grammaticalization. Linguistic Society of America Annual Meeting.