1. Introduction

Since the 1960s, the migration between China and African continent has also shown a growing and diversifying trend, with an estimated 1-2 million Chinese migrants across Africa [1]. The majority of Chinese migrants in Africa are driven by upward mobility—seeking to move to a higher social class within a hierarchy—rather than ideological reasons [2]. This process also faces significant precariousness regarding working conditions or overall livelihoods [1], creating a “mobility dilemma.” The study notes that the processes and factors of mobility and immobility in these individual cases need to be measured. However, existing related research or frameworks, such as De Haas's capability-based assessment on mobility patterns in Morocco's Valley and Kerilyn Schewel's “aspiration-capability framework” that incorporates immobility outcomes, cannot capture an individual's aspirations, capabilities and constraints. Thus, these studies are difficult to apply to each individual case. This study therefore believes that a more comprehensive framework is needed to measure (im)mobility. In this research context, after reviewing the background and characteristics of Chinese migrants in Africa, this paper proposes a further version, “Aspiration-Capability Assessment Model ” based on Kerilyn Schewel's “Aspiration-Capability Framework.” This new model quantifies an individual's aspirations and capabilities, bringing complex (im)mobility theories into individuals' daily lives through survey questionnaires, enabling everyone to understand their (im)mobility situations and locate themselves within a more detailed “Aspiration-Capability Assessment Model.” Subsequently, to clarify the immobility situations that aspiration or capability may cause, this paper will analyze the barriers to upward mobility of the Chinese migrants in Africa from three aspects: social/cultural, political, and security. Therefore, this study aims to provide insights for policymakers to reduce such barriers while modifying policies.

2. Background and characteristics of Chinese migrants in Africa

Chinese migration to Africa dates back to the 17th century, when a small number of convicts and laborers arrived [2], followed by 19th-century coastal residents seeking work amid harsh post–Opium War conditions which marking the first immigration wave to Africa [3]. Later in the 1950s-1960s, the Chinese government joined modern mobility efforts and policy-making as many African countries became independent and established diplomatic relations with China [3]. This migration, which paved the way for a new wave in the 1990s [3], also spawned small-scale but growing businesses like restaurants and retail companies [2]. The number of immigrants to Africa began to surge as China required new international trade markets beyond Europe. Africa’s abundant natural resources—such as gold and copper—also fostered long-term cooperation between the two continents [4]. This international relationship enabled China to implement various migration policies, such as the “Go Out Policy” (1990s) and the “Belt and Road Initiative” (2013) which expanded a larger mobility market for both sides, with many Chinese becoming “temporary migrant laborers or retail entrepreneurs” [5] to seek opportunities for upward mobility in Africa. However, all face social and security challenges. These challenges or views of migrants can not be generalized as a single “state agent” [5], since individual cases do not represent the experiences of everyone. Therefore, to understand the barriers each migrant in Africa faces, this paper will introduce the “Aspiration-Capability Assessment Model” in the following section to further explore this issue.

3. Analysis of migration example using the new aspiration-capability assessment model

3.1. Introduction of aspiration-capability framework

The Aspiration-Capability Assessment Model this paper designed adds practical uses to the framing and study of (im)mobility. Based on the original aspiration-capability framework as a theoretical tool [6], this expanded model incorporates a five-level scale and survey questionnaire to measure each individual's aspiration and capability. Therefore, the visualization of population data can be obtained.

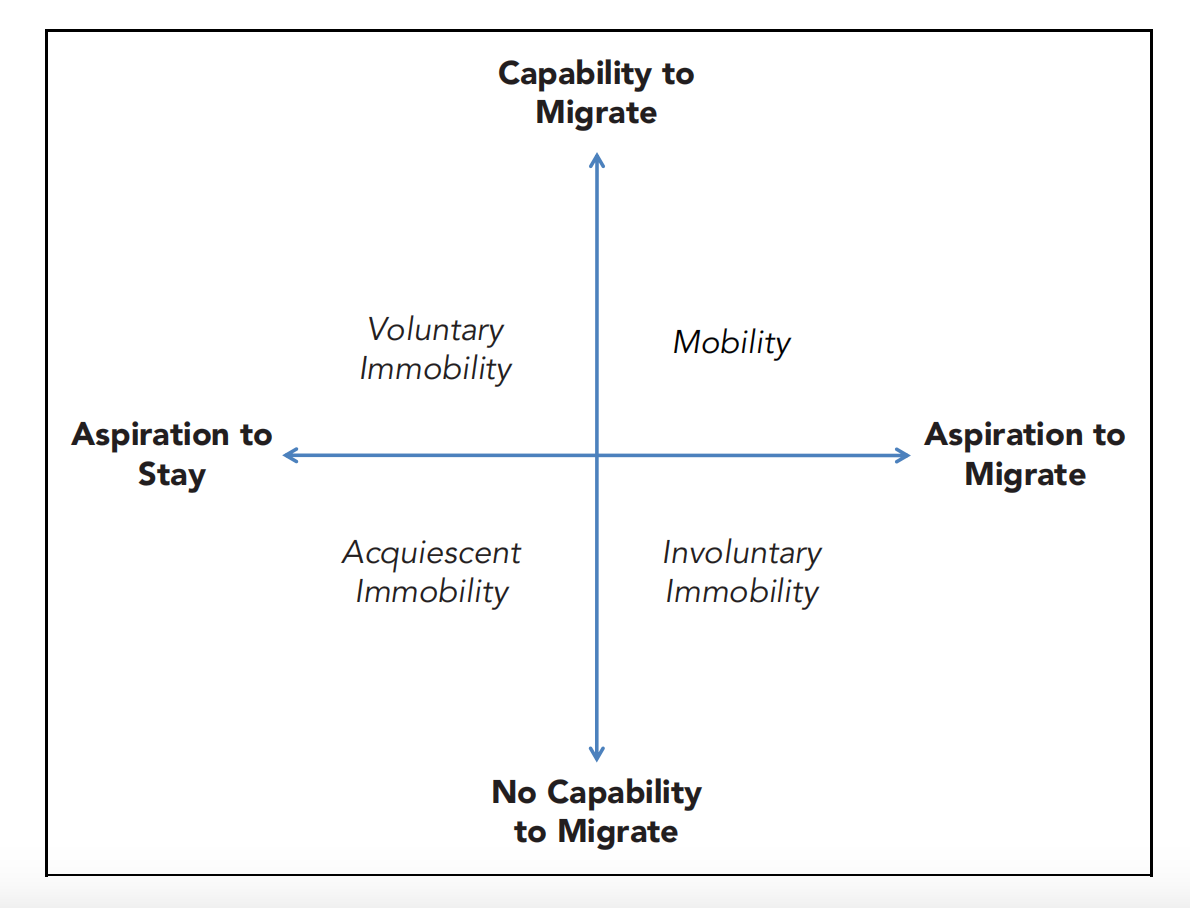

In previous research exploring the processes leading to (im)mobility, Carling first proposed the aspiration/ability model in his study of migration aspirations among Cape Verdean residents and using it as a framework to analyze migration and non-migration to demonstrate that mobility is the result of both aspiration and ability. Subsequently, Hein De Haas also emphasized in his 2003 study that migration is not only driven by low aspiration. Even under the influence of infrastructure and economic changes, individuals may still migrate through the assessment of mobility patterns in Morocco's Valley. This indicates that aspiration and capability are not always synchronized. De Haas replaced the term “ability” with “capability” to emphasize the developmental value of migration, categorizing migration into four types based on the Aspiration-Capability Framework: Involuntary, Aspirational, Voluntary Non-migration, and Migration. Kerilyn Schewel introduced the term “acquiescent”—meaning “to remain at rest”—in her 2019 study on (im)mobility to explain the factor of “voluntary immobility (non-migration).” She also adopted the modified Aspiration-Capability Framework(the framework below) as an “orienting conceptual approach” rather than a mechanism to explain how the factors of aspiration and capability relate to society.

The above research(see Figure 1) defines the foundational concepts of (im)mobility theory and the critical factors of migration: aspiration and capability. However, the study noted the need for a clear quantitative tool (questionnaire, indicator system) to be designed to measure aspiration and capability in order to determine individuals' position within the quadrant. In other words, this paper aims for the aspiration-capability model to be developed into a comprehensive quantitative tool that integrates demographic data and accounts for individual differences. Such a practical tool not only advances research on (im)mobility but also holds the potential to improve and optimize the social migration environment over the long term through government policy adjustments. Therefore, the Aspiration-Capability Assessment Model has been designed. This paper will provide a detailed introduction to this model in the following sections.

3.2. New aspiration-capability assessment model

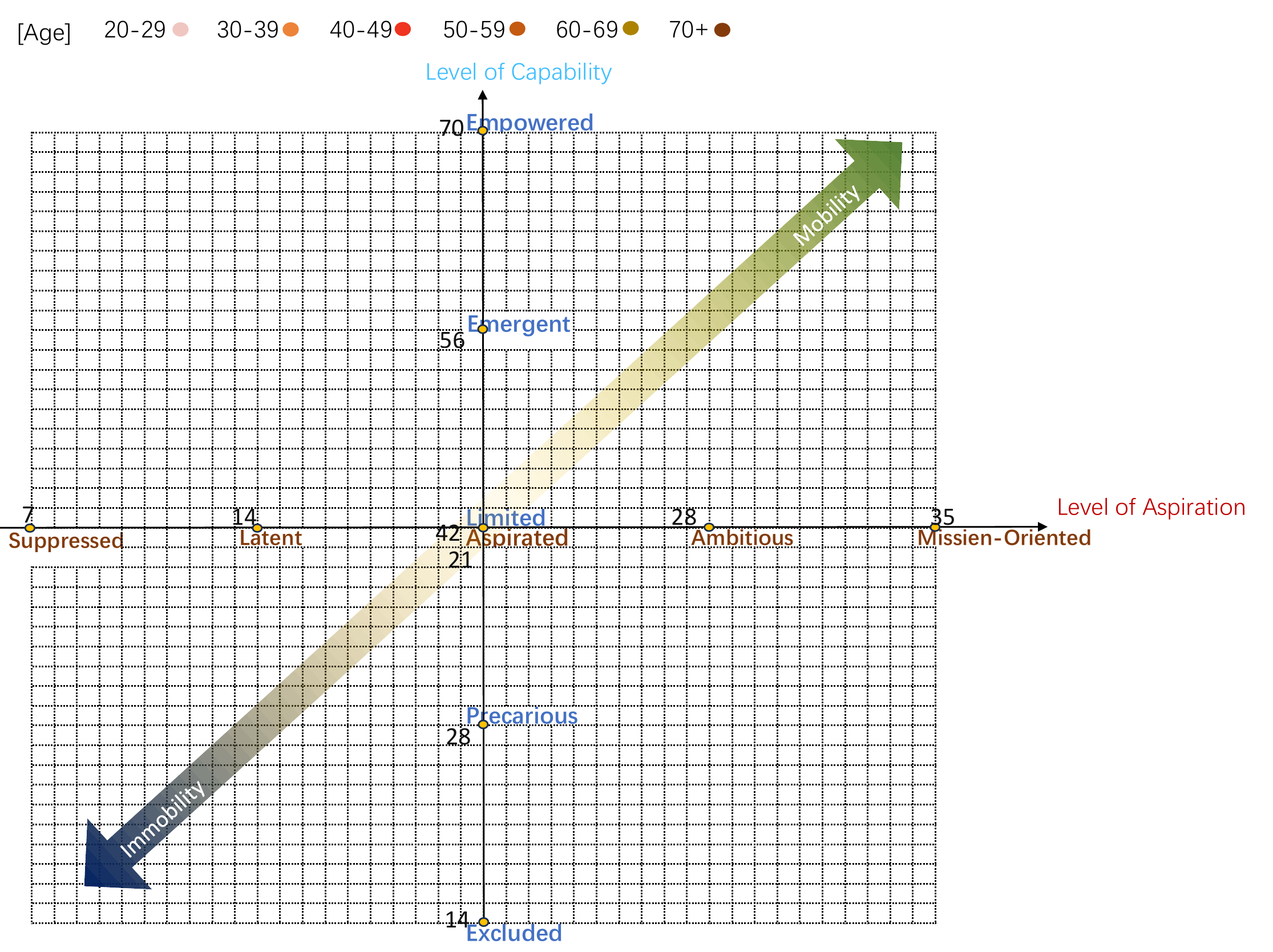

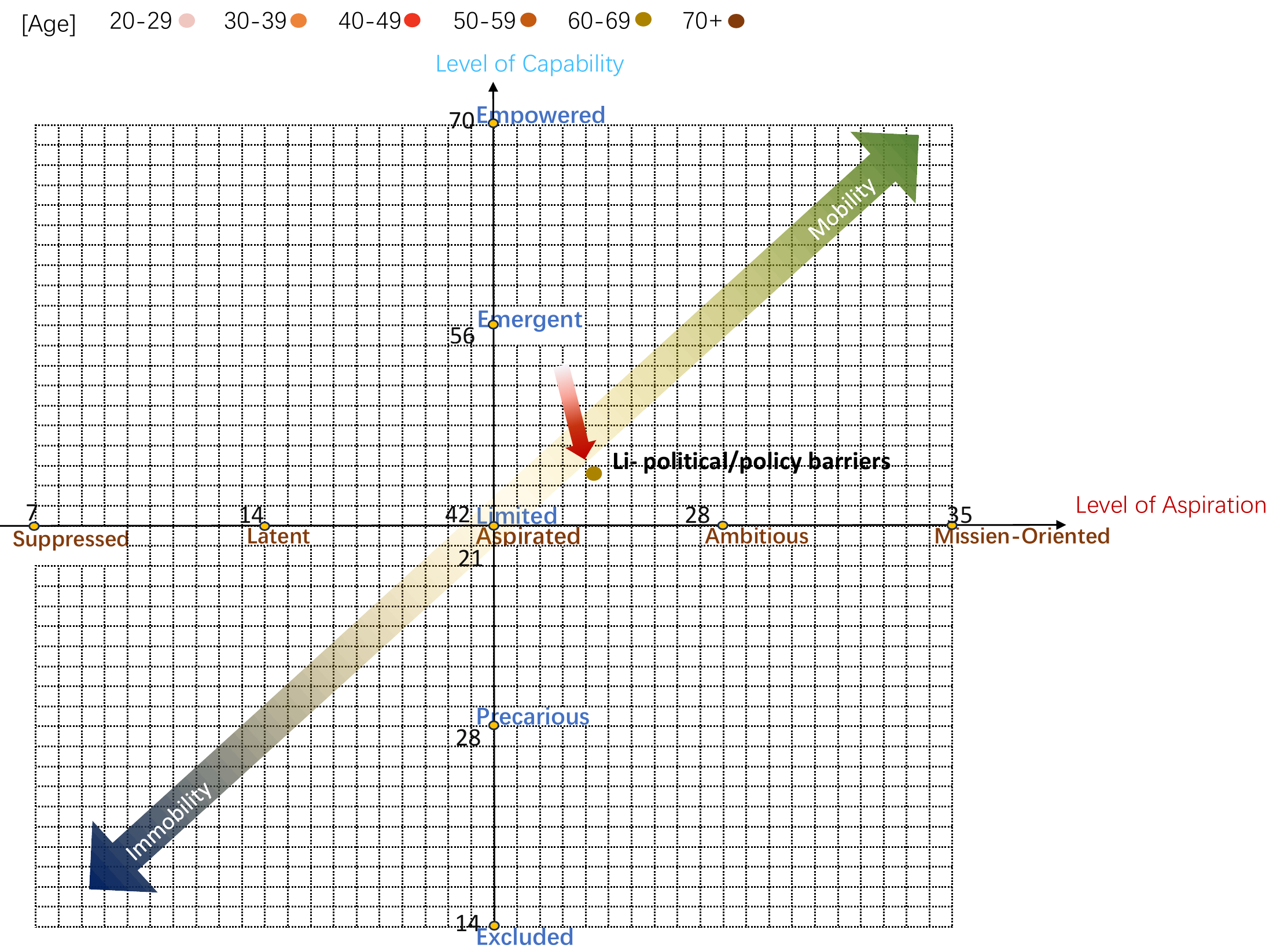

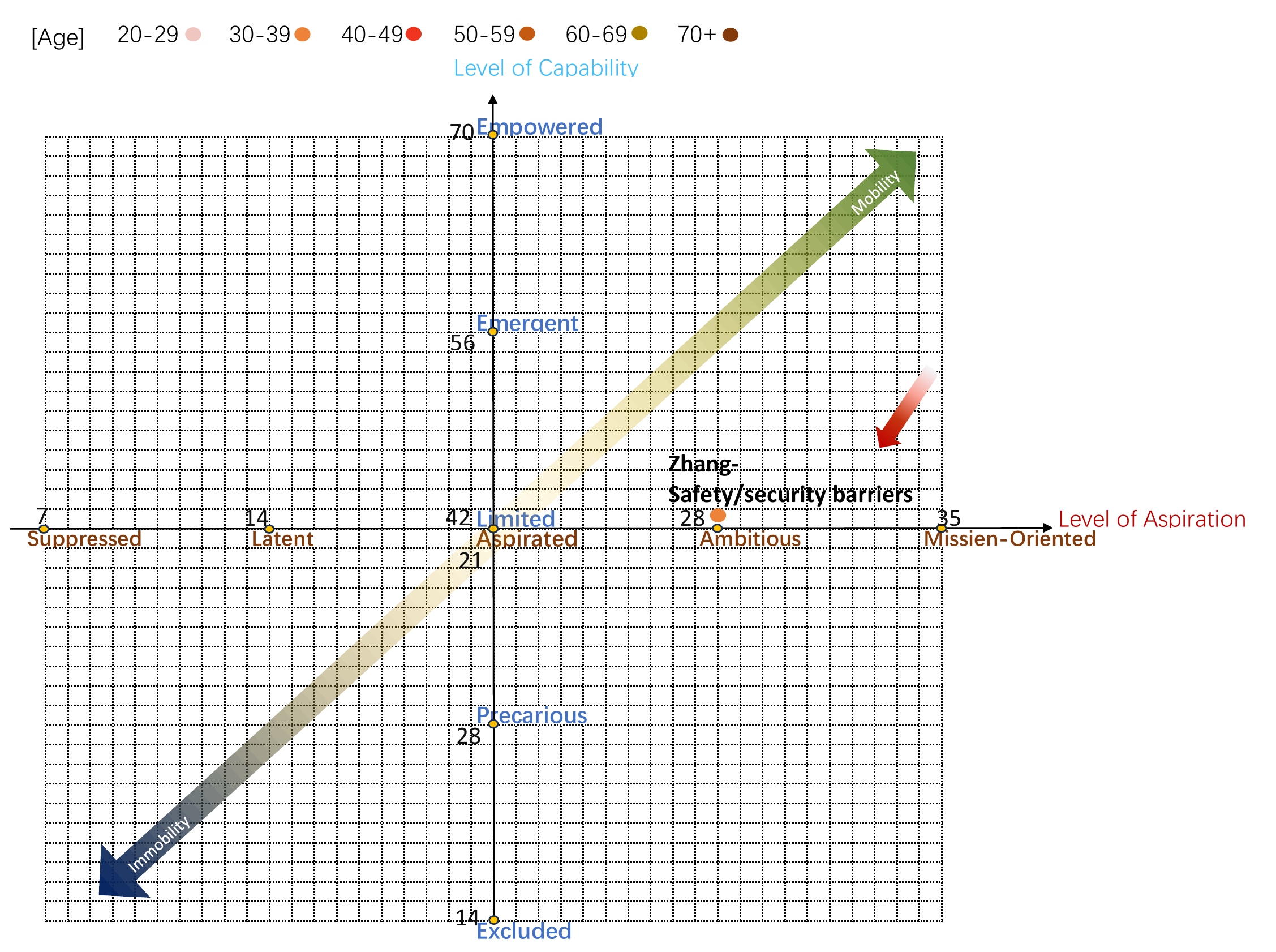

The Aspiration-Capability Assessment Model shown above is an extension of Kerilyn Schewel's Aspiration-Capability Framework (see Figure 2). Schewel's framework classifies (im)mobility, while the extended model quantifies the intersectionality of aspiration and capability and expands its applicability to individual cases that may be completely different.

The Aspiration-Capability Assessment Model continues to use a quadrant structure, where the x-axis represents “aspiration” and the y-axis represents “capability” indicators. To help individuals locate themselves more clearly in the diagram, each axis is further divided into five levels:

Aspiration levels

Suppressed: individual shows no desire or intent to move.

Latent: individual has a potential or underlying desire to move, but it is weak.

Aspirated: individual has a clear wish to move and some awareness of possible opportunities but lacks urgency or a strong plan.

Ambitious: individual has a strong intent to move, seeking opportunities.

Mission-Oriented: Individual views mobility as essential to personal goals, preparing for transition.

Capability levels

Empowered: individual has enough resources, freedom of movement, and institutional access.

Emergent: individual has possesses tools(education,skills, credentials) which are beginning to access a formal pathway to mobility(immigration).

Limited: individual has limited education or job skills, lack of capitals and networks.

Precarious: individual has slender incomes, survive in unstable settings.

Excluded: individual has no meaningful access to mobility resources, lack of basic rights.

Each data point in the model represents an individual or case, based on their aspiration and capability scores measured in the “Assessment Questionnaire.” (This paper will introduce the details of the Assessment Questionnaire in the following section.) As shown in the figure, each data point is color-coded by age group. The age limit for questionnaire respondents is 20 years or older. The purpose of selecting 20 years as the age threshold is to take into account that individuals under the age of 20 may not have the decision-making autonomy required to realize their immigration aspirations due to economic or family reasons. By adding data points color-coded by age, readers can quickly distinguish between data from participants of different age groups.

The innovation of the Aspiration-Capability Assessment Model is also achieved through a set of paired survey tools (questionnaires). The tools aim to measure respondents' aspiration and capability levels through two sets of self-assessment questions to integrate into the quadrant model.

3.3. Aspiration assessment questionnaire

The aspiration dimension of the New Aspiration–Capability Model is measured using a complementary assessment questionnaire shown below. As shown in Table 1, this section of the questionnaire consists of subjective assessment questions. The questionnaire begins with a core question—“The primary reason for immigration”—followed by each subsequent question using a five-point rating scale, covering the individual’s education, healthcare, political stability, environmental quality and employment opportunities. This study hopes these areas can serve as key factors in assessing the case’s aspiration.

|

NO |

Question |

Options |

Value |

Weight |

|

1 |

Primary reason for migration |

A. Environmental Reasons |

1 |

1 |

|

B. Higher Income |

2 |

|||

|

C. Better Education |

3 |

|||

|

D. Better Healthcare |

4 |

|||

|

E. Safety |

5 |

|||

|

2 |

Rate your country’s education system |

A. Excellent |

1 |

1 |

|

B. Good |

2 |

|||

|

C. Fair |

3 |

|||

|

D. Poor |

4 |

|||

|

E. Very Poor |

5 |

|||

|

3 |

Rate your country’s healthcare system |

A. Excellent |

1 |

1 |

|

B. Good |

2 |

|||

|

C. Fair |

3 |

|||

|

D. Poor |

4 |

|||

|

E. Very Poor |

5 |

|||

|

4 |

Rate the level of war or internal conflict in your country |

A. No conflict |

1 |

1 |

|

B. Minor tension |

2 |

|||

|

C. Localized unrest |

3 |

|||

|

D. Widespread instability |

4 |

|||

|

E. Active war |

5 |

|||

|

5 |

Rate your country’s job opportunities and living environment |

A. Excellent |

1 |

1 |

|

B. Good |

2 |

|||

|

C. Average |

3 |

|||

|

D. Poor |

4 |

|||

|

E. None |

5 |

|||

|

6 |

Rate the environmental quality |

A. Excellent |

1 |

1 |

|

B. Good |

2 |

|||

|

C. Fair |

3 |

|||

|

D. Poor |

4 |

|||

|

E. Very Poor |

5 |

|||

|

7 |

To what extent do you agree with your country’s political system or ideology |

A. Strong agreement |

1 |

1 |

|

B. Moderate agreement |

2 |

|||

|

C. Neutral |

3 |

|||

|

D. Moderate disagreement |

4 |

|||

|

E. Strong disagreement |

5 |

After participants complete the questionnaire, the resulting score ranges from 7 to 35 and is mapped onto the aspiration axis of the quadrant model. For example, if a participant is dissatisfied with their country's education, healthcare, and employment opportunities, they may lean toward the “mission-oriented” end of the aspiration axis. Through this method, an individual's aspiration level can be clearly located within the model, similar to the subsequent description of the capability assessment model.

3.4. Capability assessment questionnaire

The capability dimension of the Aspiration-Capability Assessment Model is assessed using another assessment questionnaire that includes objective questions which showns in Table 2. The questions cover factors such as health, housing stability, economic resources, and skill levels. Similar to the aspiration assessment questionnaire, each question has five answer options, scored from 1 to 5, with equal weighting. The final scores from both questionnaires will determine the participant's coordinate position within the model.

|

NO |

Question |

Options |

Value |

Weight |

|||

|

1 |

Your current health status |

A. Excellent |

5 |

1 |

|||

|

B. Good |

4 |

||||||

|

C. Fair |

3 |

||||||

|

D. Poor |

2 |

||||||

|

E. Very Poor |

1 |

||||||

|

2 |

Access to safe housing |

A. Own House |

5 |

1 |

|||

|

B. Stable Rent |

4 |

||||||

|

C. Unstable Rent |

3 |

||||||

|

D. Temporary Shelter |

2 |

||||||

|

E. Homeless |

1 |

||||||

|

3 |

Family economic situation |

A. Wealthy |

5 |

1 |

|||

|

B. Middle Class |

4 |

||||||

|

C. Low Income |

3 |

||||||

|

D. Very Low Income |

2 |

||||||

|

E. Homeless |

1 |

||||||

|

4 |

Do you have supportive personal networks? |

A. Strong Network |

5 |

1 |

|||

|

B. Moderate Network |

4 |

||||||

|

C. Weak Network |

3 |

||||||

|

D. Very Weak Network |

2 |

||||||

|

E. No Network |

1 |

||||||

|

5 |

Access to technology & internet |

A. Full Access |

5 |

1 |

|||

|

B. Frequent Access |

4 |

||||||

|

C. Occasional Access |

3 |

||||||

|

D. Rare Access |

2 |

||||||

|

E. No Access |

1 |

||||||

|

6 |

Do you have personal savings? |

A. High Savings |

5 |

1 |

|||

|

B. Moderate Savings |

4 |

||||||

|

C. Low Savings |

3 |

||||||

|

D. Very Low Savings |

2 |

||||||

|

E. No Savings |

1 |

||||||

|

7 |

Access to public services |

A. Excellent |

5 |

1 |

|||

|

B. Good |

4 |

||||||

|

C. Average |

3 |

||||||

|

D. Poor |

2 |

||||||

|

E. None |

1 |

||||||

|

8 |

Religious freedom in your country |

A. Full Freedom |

5 |

1 |

|||

|

B. Mostly Free |

4 |

||||||

|

C. Some Restrictions |

3 |

||||||

|

D. Heavily Restricted |

2 |

||||||

|

E. Banned |

1 |

||||||

|

9 |

Job skill level |

A. Highly Skilled |

5 |

1 |

|||

|

B. Skilled |

4 |

||||||

|

C. Semi-skilled |

3 |

||||||

|

D. Low Skilled |

2 |

||||||

|

E. Unskilled |

1 |

||||||

|

10 |

Ability to travel abroad |

A. Travel Anytime |

5 |

1 |

|||

|

B. Frequent Travel |

4 |

||||||

|

C. Occasional Travel |

3 |

||||||

|

D. Rarely Travel |

2 |

||||||

|

E. Cannot Travel |

1 |

||||||

|

11 |

Do you have legal residency or citizenship in your country? |

A. Full Citizenship |

5 |

1 |

|||

|

B. Permanent Residency |

4 |

||||||

|

C. Temporary Visa |

3 |

||||||

|

D. No Legal Status |

2 |

||||||

|

E. Refugee Status |

1 |

||||||

|

12 |

Debt level |

A. No Debt |

5 |

1 |

|||

|

B. Low Debt |

4 |

||||||

|

C. Moderate Debt |

3 |

||||||

|

D. High Debt |

2 |

||||||

|

E. Extreme Debt |

1 |

||||||

|

13 |

Political participation rights |

A. Full Rights |

5 |

1 |

|||

|

B. Some Rights |

4 |

||||||

|

C. Limited Rights |

3 |

||||||

|

D. Very Limited Rights |

2 |

||||||

|

E. No Rights |

1 |

||||||

|

14 |

Your highest education level |

A. Postgraduate |

5 |

1 |

|||

|

B. Undergraduate |

4 |

||||||

|

C. High School |

3 |

||||||

|

D. Primary |

2 |

||||||

|

E. None |

1 |

||||||

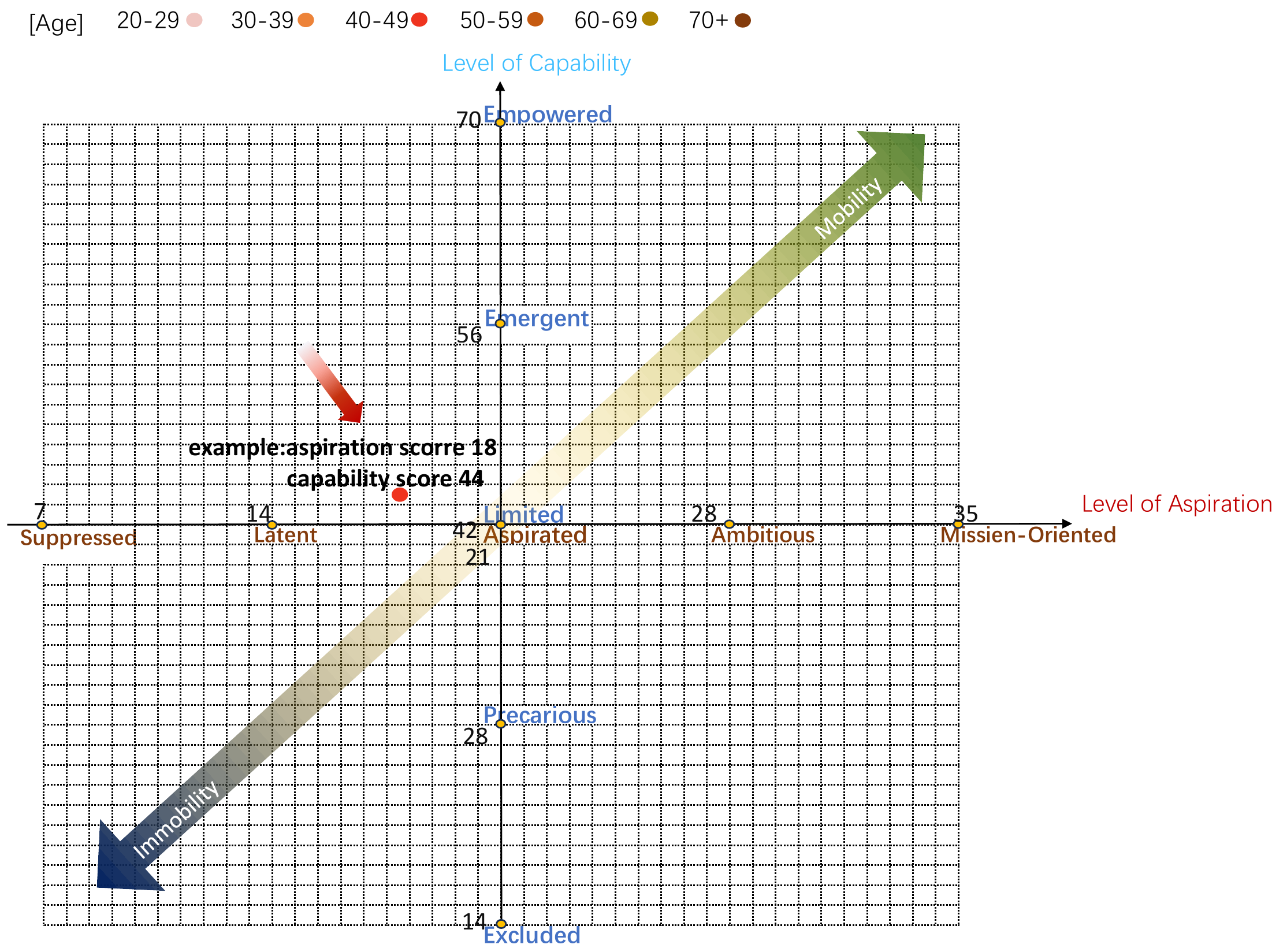

For example, a 44-year-old participant may have an aspiration score of 18 and a capability score of 44. These total scores are then plotted on the quadrant model below(see Figure 3):

This method ensures that each position reflects both subjective aspirations and objective resources, resulting in an accurate and comprehensive assessment.

It should also be noted that an individual's aspiration and capability scores may vary over time based on their sources and psychological factors, so their position on the Aspiration-Capability Assessment Model will also change. To ensure the accuracy, reliability, and completeness of questionnaire results, the “value” and “weight” columns in the assessment form are hidden from respondents. Additionally, the aspiration and capability question sets are presented to respondents in a mixed format rather than separately, preventing respondents from anticipating the scoring logic.

3.5. Pros and cons

In summary, the improvements made by the Aspiration-Capability Assessment Model contribute in three ways. Primarily, the expanded model differs from Schewel's primarily qualitative Aspiration-Capability framework by using quantitative coordinate charts of population survey data to transform the types of (im)mobility into measurable data points. It also quantifies the degrees of Aspiration and Capability into five levels, enabling future research to more clearly understand the factors determining (im)mobility.

Moreover, the assessment questionnaire introduces multiple-choice questions covering various aspects, enabling respondents to express their attitudes and resource levels more efficiently. Notably, the model can visually present large-scale population data and specific case scenarios on a single chart, allowing researchers and future policymakers to compare different individuals or groups (ex. groups of different ages or social classes) and connect macro-level mobility theories with micro-level personal realities.

Using the Aspiration-Capability Assessment Model as a new-generation tool for studying (im)mobility may face the following two criticisms. Firstly, critics may point out that while the model emphasizes the visualization of large amounts of population data, it only highlights correlations and ignores the causal relationships between social factors and variables (aspiration and capability). In fact, the Aspiration-Capability Assessment Model is a tool for studying (im)mobility and its factors, not the study objective itself. The intention behind creating this model was to lower the barrier to understanding complex information, enabling governments to adjust policies based on data. The causal relationships, meanwhile, still require exploration through future case studies.

Secondly, the Aspiration-Capability Assessment Model may be criticized for being overly generalized across different societies and cultures, unable to precisely capture the factors influencing individual aspirations and capabilities in specific social contexts. However, the model provides a set of reusable analytical tools across different scenarios, which does not mean "it ignores specific social contexts". The model was created to enable comparative analysis of population data across different societies at a macro level, offering flexibility for research. The Aspiration-Capability Assessment Model can measure an individual's willingness to migrate, and this framework is also applicable to the further mobility of migrants in their destination countries. For Chinese migrants in Africa, there are various barriers or difficulties that hinder their path to higher social classes. In the following part, this paper will discuss these barriers in detail.

4. Barriers to upward mobility: three characters

4.1. Social/cultural factors

Since the implementation of China's Belt and Road Initiative in 2013 [3], China's diplomatic influence in African countries has gradually promoted the image of Chinese immigrants and entrepreneurs. Even so, they still face many barriers to upward mobility—the ability to improve their social and economic status—at their destinations [7]. To further demonstrate the application of the Aspiration-Capability Assessment Model this paper designed, the study will analyze the barriers Chinese immigrants in Africa may encounter in their daily lives.

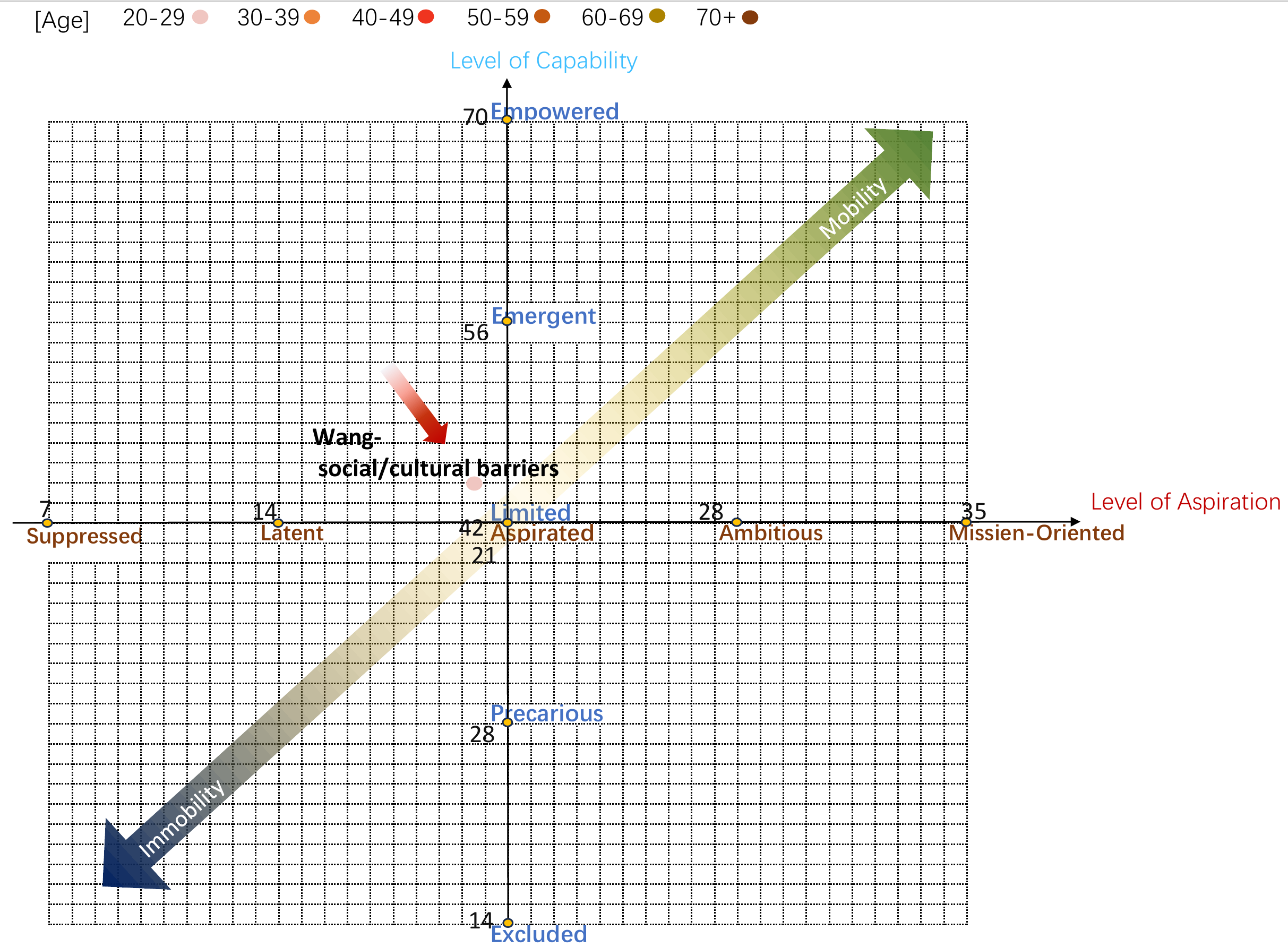

To gain a clearer understanding of the challenges these immigrants may face that hinder their upward mobility from an individual perspective, this paper created three composite characters to analyze three aspects—social/cultural, political, and safety barriers. These three characters are not real individuals but are synthesized from multiple field interviews and research studies on Chinese migrants conducted in different regions of Africa. Each character represents a specific type of barrier observed repeatedly across various real-life cases. This study will explore all the challenging situations each character might experience in the aspect of the barrier that he/she represents, complete the aspiration-capability questionnaire from their perspective, and locate these examples on the quadrant diagram.

The paper’s first concern is the social/cultural barriers. To illustrate, this study will introduce a composite character—Wang, a 23-year-old young man who wants to start a business in South Africa on his own. The most obvious challenge he faces is the language barrier [8]. Having received only limited English education in high school level China, Wang struggles to communicate—even needing a translator for medical visits—which has led to mockery from neighbors and increased the stress of living alone abroad, which is stressful for a foreign student living alone [8]. Economic challenges follow. Economic pressures quickly follow: like many Chinese migrants, Wang arrived with debt, borrowed money to start his business, and lived under heavy financial stresses for the first 2–3 years after arriving in Africa [8]. Additionally, in recent years, market saturation among Chinese businesses in South Africa has made competition more intensified and entrepreneurship increasingly difficult [8-9], especially for young entrepreneurs like Wang who lack formal business management training. With a high unemployment rate among immigrants in South Africa, Wang cannot find work in factories or apply for jobs in companies. Therefore, he chooses to start his own business by opening a store importing Chinese ceramics. Due to language barriers and differing work habits, Wang may frequently clash with his employees (who are local). For example, employees may struggle to adapt to the “clocking system” which requires strict time reporting [10]. This may lead Wang to reduce his trust in local employees. Due to the deep sense of “exclusion” and inability to integrate into the local language and culture as a foreigner in South Africa [11], Wang may experience an identity crisis—feeling confused about his own value and worldview.

Furthermore, Social barriers from marriage and family further compound his immobility. Parenthood brought significant economic pressure for education costs, making upward mobility even more difficult for Wang.

For Wang, upward mobility represents higher and income which from his small enterprise and stable legal status in Africa. This paper completed the Aspiration-Capability Assessment Questionnaire from Wang's perspective. The study answered each question based on his social, economic, and cultural background as described above. According to the calculated score, Wang is in the middle of the quadrant chart in terms of aspiration and capability, like Figure 4 shown below. This indicates that he has a certain ability and willingness toward upward mobility, but language, network, and family barriers limit his opportunities for mobility.

4.2. Political factors

The second focus of this study is on political barriers, illustrated by Li, a 65-year-old Chinese second-generation immigrant trader in a small town in South Africa whose daily choices are shaped by the long-standing historical arcs of racial segregation policies [12]. South Africa's past laws only ensured that whites enjoyed economic and social privileges [12]. Despite petitions and protests by Chinese immigrants in Africa to eliminate racial segregation, they remained powerless in the face of the law [12]. For example, the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1904 and the Black Act of 1907 (now repealed) classified Chinese as a governable category; South African citizens were further divided into White, Native, and Coloured groups, each with different treatment (Japanese were sometimes even classified as “honorary whites”) by the mid-20th century [12]. Although discrimination eased after China and South Africa established official diplomatic relations in 1976 [12], the old notion of the “Yellow Peril” still surfaces in contemporary racial politics—locals view the arrival of Asians as a threat because they reduce job opportunities and bring more competition and exploitation [13]. The issue of expired visas may also cause psychological trauma for Chinese immigrants who are sometimes arrested by the police and detained in dark rooms until influential local individuals or Chinese friends come to bail them out. Many of them subsequently abandon the idea of staying in Africa [14]. Li and her parents have experienced subtle discrimination in everyday commercial activities since the 1960s. For instance, local customers have worn the goods, gotten them dirty, and sometimes even torn them, but they would come for a refund. When Li and her parents say no, they get angry and talk loudly in front of the shop for a long time [11].

Like Wang, this study also answered the Aspiration-Capability Assessment Questionnaire from Li's perspective and located her in the quadrant diagram below based on her results in the questionnaires (see Figure 5). For Li, upward mobility means expanding her business and accessibility for better infrastructure so she can operate her business in prime commercial areas instead of less-serviced zones. Li's upper-middle-level liquidity aspiration and capability reflect that she already possesses some resources, business channels, and a certain motivation toward upward mobility, placing her in the aspired x limited area of the chart. However, residual racial discrimination hinders her when she wants to pursue larger-scale enterprises.

4.3. Safety factors

Zhang, a 32-year-old shop owner, left the big city in South Africa to develop his business in a nearby small town to escape the growing problem of crime and robbery. However, he still faces frequent burglaries and even extortion by the police—experiences of break-ins and armed robberies targeting Chinese immigrants have been widely reported [8]. Chinese people in Africa are perceived as wealthy [11], and similar robbery crimes have been reported in other countries such as Ethiopia[9]. Psychologically, repeated robberies and heightened vigilance can also damage sleep and mood, leading to negative health effects [14].

Similarly, Chinese immigrants in Africa also face physical health-related barriers. Zhang, who is not a citizen of South Africa, cannot access local health insurance. After hearing about the risks of misdiagnosis, he no longer trusts nearby clinics and instead chooses to self-medicate or wait for a Chinese doctor to treat him [15]. Furthermore, seasonal malaria has added to the anxiety of Chinese workers in the area. Since they were not informed by their employers about any malaria prevention measures, the workers lacked general awareness, and nearly everyone has unfortunately been infected [16]. Some even view this experience as a sign of “honor” and regard it as a "symbol of life in Africa [16].”

Facing scarce medical resources and high crime risks, Zhang faces barriers to upward mobility—greater safety guarantees, higher accessibility to medical resources, and stable business operations. Locating Zhang's Aspiration-Capability Assessment survey results on the quadrant model, he is in the high-aspiration/mid-low capability region of the quadrant shown below (see Figure 6). This indicates that he has a strong desire for a safer and crime-free residential and commercial environment, but actual resources such as inadequate local medical services, have trapped him in a trap of immobility, thus becoming barriers to upward mobility.

5. Conclusion

The main focus of this study is on measuring individuals' (im)mobility tendencies, emphasizing the influence of aspirations and capabilities on mobility. To this end, this paper proposes an Aspiration-Capability Assessment Model aimed at quantifying individual mobility factors, bringing (im)mobility-related theories into individuals' daily lives, and enabling everyone to locate themselves within the quadrant model through an assessment questionnaire. By analyzing three composite characters of Chinese immigrants in Africa created through a literature review, the study demonstrates that real-world situations and model coordinates are correspondingly aligned, while the model's operational feasibility and adaptability are also highlighted. Due to time and geographical constraints, real-world cases could not be used to illustrate the operational mechanism of the Aspiration-Capability Assessment Model. Therefore, the analysis results of the composite characters in this paper serve only as a reference for demonstrating the model's applicability.

Theoretically, this study expands Kerilyn Schewel's “Aspiration-Capability Framework” from a binary framework into a survey tool applicable to real-world case measurements. Practically, this study provides a reference for future research on “measuring (im)mobility.” At the macro level, it offers governments and service institutions a lightweight, comparable diagnostic mechanism for creating and revising policies. All in all, human destiny is not fixed by coordinates; as institutional barriers are gradually eliminated, the coordinates will also shift toward upward mobility.

References

[1]. Cissé, Daouda. “As Migration and Trade Increase between China and Africa, Traders at Both Ends Often Face Precarity.” Migration policy.org, 2021, www.migrationpolicy.org/article/migration-trade-china-africa-traders-face-precarity.

[2]. Park, Yoon Jung. “Chinese Migrants in Africa.” Chinese Migration in Africa Occasional Paper, No. 24, 2009, www.researchgate.net/publication/330533726_Chinese_Migration_in_Africa_Occasional_Paper_No_24.

[3]. Jedlowski, Alessandro, and Ute Röschenthaler, editor. Mobility between Africa, Asia and Latin America. Zed Books Ltd, 2017.

[4]. Vines, Alex, and Jon Wallace. “China-Africa Relations.” Chatham House, 18 Jan. 2023, www.chathamhouse.org/2023/01/china-africa-relations. Accessed 24 Aug. 2025.

[5]. Park, Yoon Jung. “One Million Chinese in Africa.” 12 May 2016, www.saisperspectives.com/2016issue/2016/5/12/n947s9csa0ik6kmkm0bzb0hy584sfo. Accessed 24 Aug. 2025.

[6]. Schewel, Kerilyn. “Understanding Immobility: Moving beyond the Mobility Bias in Migration Studies.” International Migration Review, vol. 54, no. 2, 2019, pp. 328-355. https: //doi.org/10.1177/0197918319831952.

[7]. “Upward Mobility” Www.bamboohr.com, www.bamboohr.com/resources/hr-glossary/upward-mobility. Accessed 24 Aug. 2025.

[8]. Park, Yoon Jung, and Anna Ying Chen. “Recent Chinese Migrants in Small Towns of Post-Apartheid South Africa.” Revue Européenne Des Migrations Internationales, vol. 25, no. 1, 2009, pp. 25–44. https: //doi.org/10.4000/remi.4878.

[9]. Cook, Seth, et al. “Chinese Migrants in Africa: Facts and Fictions from the Agri-Food Sector in Ethiopia and Ghana.” World Development, vol. 81, 2016, pp. 61-70. https: //doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2015.11.011.

[10]. Ankrah, Victoria, et al. “Cultural Differences on Work Relations in Chinese Companies Operating in Ghana: A Cross-Cultural Study of Chinese and Ghanaian Workers.” Heliyon, vol. 10, no. 4, 2024, https: //doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e25697.

[11]. Wood, Geoffrey, and Fang Lee Cooke. “Transient Entrepreneurs?: Chinese Migrant Small Commercial Businesses in South Africa.” Journal of International Management, vol. 29, no. 6, 2023, https: //doi.org/10.1016/j.intman.2023.101094.

[12]. Harris, Karen L. “'Whiteness’, 'Blackness’, 'Neitherness’ – the South African Chinese 1885-1991: A Case Study of Identity Politics.” Historia, vol. 47, no. 1, 2021, https: //doi.org/10.17159/hasa.v47i1.1594.

[13]. Cezne, Eric, and Roos Visser. “The Salience of Race in the Africa-China Encounter.” Global Dialogue, 15 July. 2024, globaldialogue.isa-sociology.org/articles/the-salience-of-race-in-the-africa-china-encounter. Accessed 24 Aug. 2025.

[14]. Teye, Joseph Kofi, et al. “Inter-Regional Migration in the Global South: Chinese Migrants in Ghana.” The Palgrave Handbook of South-South Migration and Inequality, 2023, pp. 319–341, https: //doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-39814-8_15.

[15]. Qiu, Jialing, et al. “Utilization of Healthcare Services among Chinese Migrants in Kenya: A Qualitative Study.” BMC Health Services Research, vol. 19, no. 1, 2019, https: //doi.org/10.1186/s12913-019-4846-y.

[16]. Zou, Li, et al. “The Perception and Interpretation of Malaria among Chinese Construction Workers in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Qualitative Study.” Malaria Journal, vol. 22, no. 305, 2023, https: //doi.org/10.1186/s12936-023-04739-4.

Cite this article

Shi,Y. (2025). Advancing Migration Research: The New Aspiration–Capability Assessment Model and Its Applications. Communications in Humanities Research,82,152-165.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceeding of ICIHCS 2025 Symposium: Exploring Community Engagement: Identity, (In)equality, and Cultural Representation

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Cissé, Daouda. “As Migration and Trade Increase between China and Africa, Traders at Both Ends Often Face Precarity.” Migration policy.org, 2021, www.migrationpolicy.org/article/migration-trade-china-africa-traders-face-precarity.

[2]. Park, Yoon Jung. “Chinese Migrants in Africa.” Chinese Migration in Africa Occasional Paper, No. 24, 2009, www.researchgate.net/publication/330533726_Chinese_Migration_in_Africa_Occasional_Paper_No_24.

[3]. Jedlowski, Alessandro, and Ute Röschenthaler, editor. Mobility between Africa, Asia and Latin America. Zed Books Ltd, 2017.

[4]. Vines, Alex, and Jon Wallace. “China-Africa Relations.” Chatham House, 18 Jan. 2023, www.chathamhouse.org/2023/01/china-africa-relations. Accessed 24 Aug. 2025.

[5]. Park, Yoon Jung. “One Million Chinese in Africa.” 12 May 2016, www.saisperspectives.com/2016issue/2016/5/12/n947s9csa0ik6kmkm0bzb0hy584sfo. Accessed 24 Aug. 2025.

[6]. Schewel, Kerilyn. “Understanding Immobility: Moving beyond the Mobility Bias in Migration Studies.” International Migration Review, vol. 54, no. 2, 2019, pp. 328-355. https: //doi.org/10.1177/0197918319831952.

[7]. “Upward Mobility” Www.bamboohr.com, www.bamboohr.com/resources/hr-glossary/upward-mobility. Accessed 24 Aug. 2025.

[8]. Park, Yoon Jung, and Anna Ying Chen. “Recent Chinese Migrants in Small Towns of Post-Apartheid South Africa.” Revue Européenne Des Migrations Internationales, vol. 25, no. 1, 2009, pp. 25–44. https: //doi.org/10.4000/remi.4878.

[9]. Cook, Seth, et al. “Chinese Migrants in Africa: Facts and Fictions from the Agri-Food Sector in Ethiopia and Ghana.” World Development, vol. 81, 2016, pp. 61-70. https: //doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2015.11.011.

[10]. Ankrah, Victoria, et al. “Cultural Differences on Work Relations in Chinese Companies Operating in Ghana: A Cross-Cultural Study of Chinese and Ghanaian Workers.” Heliyon, vol. 10, no. 4, 2024, https: //doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e25697.

[11]. Wood, Geoffrey, and Fang Lee Cooke. “Transient Entrepreneurs?: Chinese Migrant Small Commercial Businesses in South Africa.” Journal of International Management, vol. 29, no. 6, 2023, https: //doi.org/10.1016/j.intman.2023.101094.

[12]. Harris, Karen L. “'Whiteness’, 'Blackness’, 'Neitherness’ – the South African Chinese 1885-1991: A Case Study of Identity Politics.” Historia, vol. 47, no. 1, 2021, https: //doi.org/10.17159/hasa.v47i1.1594.

[13]. Cezne, Eric, and Roos Visser. “The Salience of Race in the Africa-China Encounter.” Global Dialogue, 15 July. 2024, globaldialogue.isa-sociology.org/articles/the-salience-of-race-in-the-africa-china-encounter. Accessed 24 Aug. 2025.

[14]. Teye, Joseph Kofi, et al. “Inter-Regional Migration in the Global South: Chinese Migrants in Ghana.” The Palgrave Handbook of South-South Migration and Inequality, 2023, pp. 319–341, https: //doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-39814-8_15.

[15]. Qiu, Jialing, et al. “Utilization of Healthcare Services among Chinese Migrants in Kenya: A Qualitative Study.” BMC Health Services Research, vol. 19, no. 1, 2019, https: //doi.org/10.1186/s12913-019-4846-y.

[16]. Zou, Li, et al. “The Perception and Interpretation of Malaria among Chinese Construction Workers in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Qualitative Study.” Malaria Journal, vol. 22, no. 305, 2023, https: //doi.org/10.1186/s12936-023-04739-4.