1. Introduction

According to the 2024 China Gaming Industry Report, the actual sales revenue of the domestic game market in 2024 reached 325.782 billion RMB, with the number of game users reaching 674 million [1]. With the rapid development of the internet, online games, as part of social activities, have become an important vehicle for communication in the public sphere. In 2025, the communities and cultures formed by online games have become significant subjects for academic research. The viral popularity of the HELLDIVERS 2 "Heart of Democracy" event, which generated widespread impact beyond its original gaming community, warrants further examination regarding its role in constructing collective identity across communities.

Research on group identity has a long history domestically and internationally. In recent years, international scholars have primarily focused on issues of national, regional, and ethnic identity. In the era of digital communication, many scholars have also begun to explore the challenges faced by group identity. For instance, Guo Lin and Long Xiaonong discussed the challenges of governance and group identity formation in the digital communication era [2]. Group identity in the digital communication era has emerged as a new topic.

Regarding research on group identity within internet-based interest groups, domestic scholars primarily analyze specific cases to study the psychological motivations of group members and the construction process of group identity. Theoretical outcomes remain relatively scarce. However, Cui Zhenghao summarized literature suggesting that individuals join online interest groups to obtain group identity, thereby achieving self-value confirmation (i.e., self-identity). This process is dynamic; once members gain self-identity, they reciprocally influence the construction of group identity [3]. Building on this finding, this paper uses the HELLDIVERS 2 "Shanghai Defense Campaign" event as a case study to explore the impact of group identity on the development of cultural industries.

This paper takes the HELLDIVERS 2 "Heart of Democracy" event as its main subject. Utilizing a combined approach of content analysis, comparative analysis, and survey methods,it investigates the process through which group members form group identity by participating in player-driven narrative events and the impact of this process.

2. Collective Memory and group identity in the internet era

"Collective Memory" was initially proposed by French sociologist Maurice Halbwachs and art historian Aby Warburg. They argued that collective memory is a group's identification with its own cultural specificity [4]. Social memory gained widespread acceptance in academia starting from the 1950s, becoming an important theory connecting sociology, psychology, political science, anthropology, history, and literature [5]. Pei Fei proposed that 20th-century writings on war trauma altered many nations' understandings of history, the world, and politics, and also reconstructed the cultural identity of generations. The frequent recollection of war atrocities in literature implanted a collective awareness of trauma among ethnic groups and populations who did not directly experience these sufferings [6].

In his work Les Lieux de Mémoire (Sites of Memory), Pierre Nora emphasized the constructed nature of "collective memory" and its close relationship with "sites of memory" [7]. Li Yanhui and Zhu Hong, in their study of the old site of the Whampoa Military Academy as another site of memory, proposed that the War of Resistance Against Japan is the collective memory of all Chinese people. Re-enacting resistance against Japan serves to evoke visitors' collective memory [8]. Placing "sites of memory" on an internet platform would yield similar effects. As Shi Xianzhi suggests, the vigorous development of digital technology profoundly reshapes the writing of collective memory, leading to significant digital transformations in aspects such as subject identity, content construction, resource storage, and functional mechanisms [9]. Shao Peng, Zhao Ruoyi, and Pan Zhongjing also argue that online "sites of memory" formed by social media become spaces and symbols for online commemorative activities. By aggregating users' "digital traces" of participation, they function to sustain, influence, and shape collective memory [10]. In the internet era, the construction of "sites of memory" has begun to detach from physical carriers, becoming internet symbols that use information as the medium to undertake the responsibility of building collective memory.

Robert D. Putnam's understanding of traditional association activities in American society was that new groups based on shared interests gradually emerged, but members knew little about each other, and participation in group activities and social interaction among members was limited [11]. In the internet era, the scale of such new groups has expanded rapidly. As emerging cultural products online, online games could potentially become carriers for constructing "sites of memory." Games could link common collective traumatic memories across cultural groups, forming new cross-cultural group identities using gaming communities as the medium. Based on this hypothesis, this paper uses HELLDIVERS 2 as an example to study how online games construct "sites of memory." The case itself possesses timeliness and typicality.

This paper will employ content analysis, comparative analysis, and survey methods to study the "Heart of Democracy" event, including its content, dissemination methods, community content, and communication effects.

3. Research methods

3.1. Content analysis

Official account activity, promotional videos and related content posted on the video platform www.bilibili.com were screened. Using event keywords and specific content relevance as defining criteria, a total of 5 event-related promotional videos and 12 promotional graphics/text posts were selected. This was combined with an analysis of user-generated content (UGC) posted by users in relevant discussion groups on overseas platforms X and Discord to analyze the event and game format.

3.2. Comparative analysis

By selecting content related to similar events for this game, 102 promotional videos (excluding videos related to this specific event) posted by the official account on www.bilibili.com between July 12, 2024, and July 12, 2025, were chosen. Their promotional strategies and game content were comparatively analyzed.

3.3. Survey method

The game is currently available on the PS5 console platform and the Steam game platform. Using the Steam official historical player count website steamcharts.com, data from May to July 2025 was selected to analyze historical monthly average concurrent players and the percentage change compared to the previous month. Simultaneously, 6432 Chinese-language reviews from the Steam store page customer reviews between May and June 2025 were selected to analyze user evaluations.

According to the Q1 2025 financial report of video platform www.bilibili.com, as analyzed by Lanshi Wendao, Bilibili has 165 million active game users, with an average daily usage time exceeding 60 minutes, indicating user stickiness far surpassing that of short video platforms [12]. This demonstrates that the site provides sufficient data volume to support the survey. Using video content on www.bilibili.com, videos posted between May and June 2025 were filtered using the keyword "HELLDIVERS 2" , resulting in 8775 video entries captured for analysis.

4. Research results

4.1. Core gameplay and event core gameplay design

The core gameplay of HELLDIVERS 2 is essentially "Controlled Chaos": It creates high uncertainty through procedurally generated environments, friendly fire mechanics, resource limitations, and dynamic enemy behavior. This is counterbalanced by providing players with tools via a teamwork framework, modular equipment system, and efficiency-oriented progression mechanics. Its design success lies in transforming "mistakes" (such as accidentally killing teammates) into elements of social entertainment, while deepening replay value through continuous content updates, forming a unique cooperative shooting paradigm.

The "Heart of Democracy" event is a player-driven narrative activity based on the core gameplay. Players fight against alien invaders in fictional regions on a fictional Earth. Stage-based regional unlocking and visualizable defense progress serve as the core quantitative standards for the event, driving the event's storyline. The open regions all allude to well-known real-world cities, such as York Supreme (New York), Port Mercy (Singapore), Prosperity City (Stockholm), and Equality-On-Sea (Shanghai).

4.2. Game promotion strategy

In the event's promotional trailer, the game's official channel adopted the format of a military recruitment advertisement to showcase the event's core gameplay and content, heavily referencing the production style of political propaganda films. This included emphasizing slogans like "Democracy" and "Freedom," and promoting "Managed Democracy" (which in the game manifests as a glorification of authoritarian politics). Combined with the game's events and updates since launch (April 2024 - July 2025), this promotional approach is part of its core strategy. An attitude of actively responding to user feedback and UGC content was also observed. For example, based on the high failure and death rates in the in-game mission "Malevelon Creek," a memorial day was established, and commemorative cosmetic capes were distributed both in and out of the game.

4.3. User feedback and UGC content

Based on Steam historical player data, active player counts in May increased by 115.59% compared to April. The daily average number of players was approximately 60,291.3, with a peak concurrent player count of 162,997.

Analysis of Steam Chinese user reviews revealed that out of 6432 reviews, only 29% were positive. Sorting by "Most Helpful Reviews" (based on upvotes from other users), 8 out of the top 10 reviews contained negative feedback about the event, primarily questioning and expressing dissatisfaction with the developer's preset narrative outcome for this player-participation narrative event.

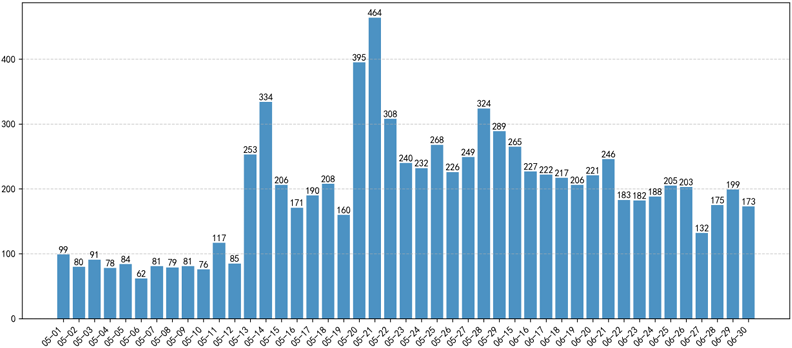

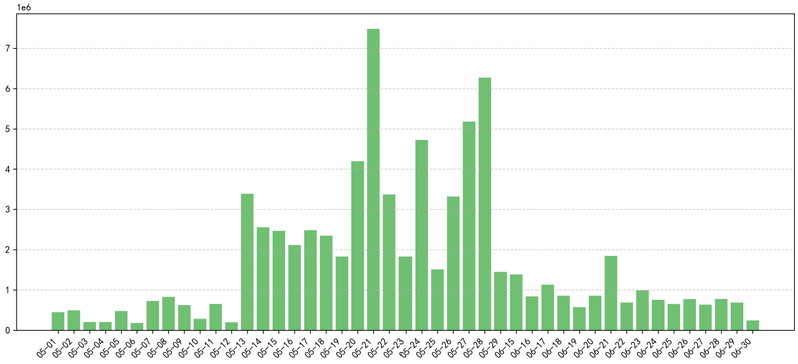

Analysis of 8775 videos on the video website Bilibili between June and July 2025 yielded the data results shown in Figure 1 and Figure 2.

Figures 1 and 2 show that discussion and attention towards the game within the player community surged significantly starting from May 12th when the event began. Daily release volume increased markedly, and the highest daily view count during the event period reached 7,485,253.

Analysis of over 8,000 videos revealed that more than 70% of the content consisted of player gameplay footage/livestreams. Sorting by view count in descending order, among the top 50 videos by views, 28 were UGC derivative works, 6 were official promotional content, and the remainder included game guides, information from foreign websites, and event progress reports.

Analysis of promotional images and videos independently created by the game community showed that most content adopted styles similar to Cold War-era or World War II-era posters or propaganda materials. Slogans like "Super Songhu Defense Campaign" and "Defend Shanghai" were frequently used. A widely circulated poster featured Shanghai landmarks such as the Oriental Pearl Tower and the Bund buildings, using retro poster design with dominant colors of orange-red and maroon-red to create strong visual contrast. The combination of building silhouettes and explosive flames constructed impactful imagery.

5. Discussion

5.1. Spontaneously constructed sites of memory: developer guidance of the community

The event's core content, through its entertaining and exaggerated sci-fi political backdrop combined with reality, served to dissolve political seriousness and avoid politically sensitive topics. Beyond unified game content promotion, the developer's official promotion heavily relied on localized content as the primary video strategy, catering to local culture and strengthening cross-cultural communication.

Analysis of user UGC content reveals that the gaming community exhibited a positive attitude towards this event. The community spontaneously propagated slogans like "Cyber Songhu Defense Campaign" and "Defend Shanghai" across gaming communities, forming unique cultural symbols that attracted new players. Significant efficient communication and mutual assistance were also achieved in cross-regional community interactions.

The event primarily formed historical intertextuality between in-game scenarios and real-world battles. It provided a virtual space for constructing "sites of memory." The community spontaneously integrated universal group historical memories about war into the scenarios provided by the event, constructing a cross-cultural collective identity and forming sites of memory.

Within the field constructed by this event, game scenarios and real-world battles formed historical intertextuality. Simultaneously, the role played by users was rendered ambiguous, endowing it with plasticity and enabling user reinterpretation. Within the space provided by the game, cross-cultural user groups spontaneously combined universal group historical traumatic memories about war with the event's scenarios. This fused the collective memories of various cultures, creating a vast "site of memory."

The overall path to cross-cultural group identity formation in this event can be summarized as: 1) Providing a space for constructing sites of memory through intertextuality formed by resisting external threats and WWII history; 2) Utilizing group historical traumatic memory, prompting the community to spontaneously combine game scenarios with cultural group memories to build sites of memory; 3) Based on historical traumatic memory, constructing a compensation mechanism through the activity of fighting invaders, thereby strengthening group cohesion and enhancing player activity. Considering community activity levels and player counts during the event period (May 12, 2025 - May 31, 2025), the event achieved significant success at the promotional level.

5.2. "False" player-driven narrative: community-developer opposition

Analysis of Steam user reviews and UGC content on Bilibili reveals that although the gaming community showed great enthusiasm for the event, user reviews contained substantial negative feedback. This included dissatisfaction with the event's planning content and skepticism regarding the developer's predetermined script.

Most users believed the game developer employed a predetermined script, which severely undermined player motivation to participate in the narrative and led to negative user feedback, consequently resulting in opposition between the community and the developer.

6. Conclusion

This study employed content analysis, comparative analysis, and survey methods, utilizing theories of sites of memory and group identity to discuss the methods and strategies used by the HELLDIVERS 2 "Heart of Democracy" event in guiding its community. It summarized the benefits and risks of this strategy. However, this study was limited to Chinese social media communities and communities on some social media platforms in other countries as research samples, restricting its applicability within the game's global community. Furthermore, the study focused solely on HELLDIVERS 2 itself, lacking horizontal comparisons, thus possessing certain limitations and potential one-sidedness.

Summarizing the research findings, for the gaming industry, deconstructing history to guide communities in spontaneously forming sites of memory can indeed enhance and promote community formation and expansion. However, it inevitably generates opposition, particularly in player-driven narrative game content.

For similar cultural products, creators may need to adopt a more open perspective and attitude when communicating with the community to avoid creating an antagonistic relationship between creators and the community.

References

[1]. None, (2025) Annual Development Overview of China's Game Industry—Based on Data from the 2024 China Game Industry Report. China Digital Publishing, 3(01): 61-66.

[2]. Guo, L., Long, X.N., (2022) National Governance and Group Identity in the Digital Communication Era: A Perspective of Historical Change Theory . China Journalism and Communication Research, (03): 215-226.

[3]. Cui, Z.H., (2020) Research on Group Identity in Interest-Based Communication of Online Games Based on Honor of Kings. Communication University of Zhejiang.

[4]. Ernest, G., Warburg, A., (1970) An Intellectual Biography . London: The Warburg Institute, 323.

[5]. Aleida, A., (2004) Four Formats of Memory, From Individual to Collective Construction of the Past. Cultural Memory and Historical Consciousness in the German-speaking World since 1500. Bern: Peter Lang, 22-25.

[6]. Pei, F., (2016) History and National Cultural Reconstruction in Collective Memory. Journal of Hefei University (Comprehensive Edition), 33(03): 34-38.

[7]. Nora, P., (2015) Sites of Memory: The Cultural and Social History of French National Consciousness. Huang Yanhong, et al., trans. Nanjing: Nanjing University Press, 1.

[8]. Li, Y. H., Zhu, H., (2013) Local Legends, Collective Memory, and National Identity: A Study Centered on the Old Site of the Whampoa Military Academy and Its Visitors. Human Geography, 28(06): 17-21.

[9]. Shi, X. Z., (2025) Digital Writing of Collective Memory: A New Anchor Point for Enhancing Public Identification with Mainstream Ideology [J]. Journal of Nanjing Normal University (Social Science Edition), (03): 98-106.

[10]. Shao, P., Zhao, R. Y., Pan, Z .J., (2024) Digital "Sites of Memory": Reconstruction of Martyrs' Commemorative Space in Social Media. Journal of Zhejiang University (Humanities and Social Sciences), 54(05): 29-41.

[11]. Putnam, R. D., (2002) Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community.

[12]. None, (2025) Analysis of User Demographic Characteristics in the Gaming Industry on Bilibili, Retrieved from https: //www.bilibili.com/opus/1060417203406372885?spm_id_from=333.1387.0.0

Cite this article

Ye,X. (2025). Research on Group Identity Based on the "Heart of Democracy" Event in HELLDIVERS 2. Communications in Humanities Research,83,97-103.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of ICIHCS 2025 Symposium: Voices of Action: Narratives of Faith, Ethics, and Social Practice

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. None, (2025) Annual Development Overview of China's Game Industry—Based on Data from the 2024 China Game Industry Report. China Digital Publishing, 3(01): 61-66.

[2]. Guo, L., Long, X.N., (2022) National Governance and Group Identity in the Digital Communication Era: A Perspective of Historical Change Theory . China Journalism and Communication Research, (03): 215-226.

[3]. Cui, Z.H., (2020) Research on Group Identity in Interest-Based Communication of Online Games Based on Honor of Kings. Communication University of Zhejiang.

[4]. Ernest, G., Warburg, A., (1970) An Intellectual Biography . London: The Warburg Institute, 323.

[5]. Aleida, A., (2004) Four Formats of Memory, From Individual to Collective Construction of the Past. Cultural Memory and Historical Consciousness in the German-speaking World since 1500. Bern: Peter Lang, 22-25.

[6]. Pei, F., (2016) History and National Cultural Reconstruction in Collective Memory. Journal of Hefei University (Comprehensive Edition), 33(03): 34-38.

[7]. Nora, P., (2015) Sites of Memory: The Cultural and Social History of French National Consciousness. Huang Yanhong, et al., trans. Nanjing: Nanjing University Press, 1.

[8]. Li, Y. H., Zhu, H., (2013) Local Legends, Collective Memory, and National Identity: A Study Centered on the Old Site of the Whampoa Military Academy and Its Visitors. Human Geography, 28(06): 17-21.

[9]. Shi, X. Z., (2025) Digital Writing of Collective Memory: A New Anchor Point for Enhancing Public Identification with Mainstream Ideology [J]. Journal of Nanjing Normal University (Social Science Edition), (03): 98-106.

[10]. Shao, P., Zhao, R. Y., Pan, Z .J., (2024) Digital "Sites of Memory": Reconstruction of Martyrs' Commemorative Space in Social Media. Journal of Zhejiang University (Humanities and Social Sciences), 54(05): 29-41.

[11]. Putnam, R. D., (2002) Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community.

[12]. None, (2025) Analysis of User Demographic Characteristics in the Gaming Industry on Bilibili, Retrieved from https: //www.bilibili.com/opus/1060417203406372885?spm_id_from=333.1387.0.0