1.Introduction

In the last few decades, video gaming has become one of the most popular types of entertainment. The value of the video game market in the U.S. has reached $90.13 billion USD in 2022, far exceeding the $40 billion USD movie industry [1][2]. With the amount of wealth at play, the influence of the industry is huge, creating uncountable jobs in game development, publishing, retail, e-sports, hardware manufacture, and continually impacting popular culture worldwide. Despite its enormous scale, the video game industry excludes and misrepresents women to a great extent. Prior research has mostly focused on the effects of sexualization, gender segregation in the video game industry, and sexual harassment in online video games. For example, Behm-Morawitz, E., & Mastro, D. found that exposure to sexualized female video game characters leads to lower female self-efficacy and impacts beliefs of women in the real world. Tompkins, J. E., & Martins, N. found that the male-centric character design has been a normalized practice in the video game industry, and changes that challenge the masculine norm are discouraged due to the favor of the status quo [3][4]. Few studies have examined the relationship between the historical male-dominated establishment of the video game industry and its present sexualization and exclusion of women. This study examined and arranged prior studies on video games and gender equality in a systematic manner to find out how the male-centric industry establishment that excludes women has been founded. The paper will explore: 1) the history of the male-dominated industry; 2) the failure of properly representing women; 3) the exclusionary structure; and 4) the recent rise of female voices. Investigating gender equality in the video game industry context is crucial for the diversity of our societies. As the video game industry has become a multibillion-dollar industry and one of the most influential forms of entertainment, its impact has never been greater. Revealing the flaws of the industry will encourage changes to happen, which will result in a more inclusive world for all of us.

2.History: Male-dominated Structure

The video game industry nowadays includes a variety of specialties, including game production, game design, game development, etc. [5]. However, when the industry was initially started, the pioneers were largely electrical engineers and computer scientists, given how video games are heavily dependent on computers. These occupations happen to be mostly taken by men because far more men pursue the path of computer science than women. One of the earliest video games, “Pong”, was designed by male engineer Allan Alcorn. The Atari company he worked in was founded by Nolan Bushnell and Ted Dabney in 1971 — they are both male electrical engineers.

The video game industry has been a male-dominated industry since it was created, and it suffers from a lack of female voices. Despite the fact that female gamers in the United States reached 48% in 2022, nearly half of the population, a 2021 survey of game developers revealed that there were only 30% of female developers globally, compared to 61% of male developers — more than twice as many as female developers [6][7]. With the video game industry established by men, the pioneers first designed games with men in mind. Historically, computer games have tended to be targeted toward male audiences, and the male has been recognized as the default gender of computer games [8]. Because of that, women characters in video games are both underrepresented and often portrayed in an overly sexualized manner to appeal to the male market [8].

One explanation for this phenomenon is that the industry views men as the main consumers of video games. The video game industry recognizes its core gamers to be heterosexual white males, indicating that this market segment is thought to have the greatest influence on the success and revenue of video games [4]. This market logic may have forced the industry to support the sexualized representation of women and to maintain the status quo of male-centric appeals. On the other hand, the industry is reluctant to adopt innovative material that challenges the male-centric status quo, out of concern that the target consumers consisting of heterosexual white males would not readily accept it [4]. This situation is potentially dangerous — it creates a self-reinforcing cycle of production and consumption that reaffirms heterosexual white males as the targeted audience, player, and game developer. It makes marginalized identities such as women, people of color, and LGBT communities especially vulnerable due to misrepresentation and isolation from the hetero-masculine ingroup to the marginalized outgroup [4][9].

3.Failure of Proper Representation

3.1.“Bikini Armors” — Women’s Power Come from Sexualization

A distinctive difference between female and male characters in video games is how their power is conveyed through appearance. While men’s power, intelligence, and capability in video games are typically illustrated through physical strength and appropriate attire, female game developer Shelby Carleton explicitly pointed out during her TEDx Presentation that “women’s power comes from their sexualization” [10].

Studies have shown that female sexuality is usually emphasized through highly revealing clothing. 70% of female characters in Mature-rated video games and 46% of female characters in Teen-rated video games were portrayed as having excess cleavage; 86% of female characters were portrayed as wearing clothing with low or revealing necklines; 48% of female characters were dressed in outfits with no sleeves. Contrastingly, just 22% of male characters wear attire without sleeves, and only 14% of male characters wear apparel with low or revealing necklines. Additionally, women were twice as likely as men to be seen wearing revealing attire [3].

Figure 1: Jade from Mortal Kombat 2011 [11]. Figure 2: Scorpion from Mortal Kombat 2011 [12].

“Bikini Armor” is a good example of this. Women are sexualized in a wide variety of games where female warriors are designed to wear very few pieces of clothing and armor that only cover their breasts and bikini areas, leaving the rest of their bodies exposed, but their male counterparts are made to wear a lot of defensive equipment that seems to protect the character well. As shown in Figure 1, in the fighting game Mortal Kombat 2011, female fighter Jade wears a green one-piece bikini costume that displays a large proportion of her upper body and thigh areas, which fully displays her sexiness. Figure 2 displays the male warrior Scorpion covering his body more thoroughly with full-body armor that only leaves his upper arm muscles to be seen, signifying his physical strength.

These features of character design adhere to idealized gender representations. Female and male characters are specifically designed in this way to appeal to heterosexual male desire [4]. Women are seen as attractive when their alluring appearance is paired with a strong personality, and men are constructed as powerful, in control, and heroic to fit the “aspirational” assumptions of the core male audience [4].

Figure 3: King of Fighters (1994) [13]. Figure 4: King of Fighters (1994) [13].

Also notably, in another fighting game series King of Fighters, “clothes-rip” effect is used as another way to sexualize the female in-game characters. As shown in Figure 3 and Figure 4, once a female character is being defeated with the last strike, her costume may get torn apart after the knockout, leaving her with ripped clothes and underwear — and sometimes no underwear. In King of Fighters, this effect has been used for the female fighters only, not a single male fighter has the same “clothes-rip” effect with them. This implies that female characters use their sexual appeals to compensate for their loss of power, which again proves that their power is exhibited through sexualization.

3.2.Lack of Agency and Acting as Secondary Characters

Many video games exhibit a lack of women’s agency by portraying women as secondary characters that constantly need the male protagonists to save them. Women either serves as victim or prizes, with stereotypical gender roles added upon them as brazenly sexualized beings and object of desire [3]. In the video game series Super Mario Brothers, Princess Peach, the primary female character of the game, has either being captured by the antagonist Bowser or being rescued by main character Mario since 1985 [10]. In the survival horror game Resident Evil 4, the main protagonist Leon S. Kennedy is ordered to rescue Ashley Graham, the daughter of the fictional U.S. President. Ashley has been kidnapped by a mysterious cult organization in Spain, and she would be captured repeatedly throughout the game, making Leon rescue her over and over. These widely used character designs represent women as powerless, either depicted as sex objects or damsels in distress [9]. These designs may be attracting to sexist players, but they also may reinforce sexist attitudes that are already present [9].

3.3.Effect of Misrepresentation

Misrepresenting women as sexualized and powerless prizes in video games has serious implications as it influences people’s beliefs in the real world. Studies have revealed that women playing the sexualized heroine would lead to reduced self-efficacy compared to playing the non-sexualized heroine or playing no video game at all [3]. As overly sexualized bodies have become the most noticeable feature in female characters, women video game players may feel less confident in their capacity to thrive in the real world if they are exposed to sexualized pictures [3]. In addition, playing sexualized female characters in video games would cause both male and female players to have fewer positive attitudes toward women [3]. It would also lead to increased negative gender stereotypes on women’s cognitive capabilities and less favorable perceptions on women’s physical abilities among players [3]. In a similar fashion, the dramatically increased proportion of male characters as primary characters may contribute to the perception that women are subordinate in real-world circumstances [14]. Short-term exposure to sexually objectified female video game characters made males more tolerant of real-life assault against women, and long-term exposure made men more tolerant of sexual harassment and rape myths [15]. Sexist video game material leads to sexist attitudes toward women and rape myth acceptance. The objectification of women in sexually graphic video games desensitizes men to sexist attitudes toward women, according to a study of male college students. The participants’ propensity of sexism also increased [15]. These findings are aligned with previous studies, which demonstrated that objectified and degrading portrayals of women impact how real people feel about women in general and the women they are romantically involved with [14].

4.Exclusionary Structure — Women Not Welcomed

Women are excluded from the video game industry in three ways. Firstly, due to the sexualized nature of many games, they feel uncomfortable playing them. Secondly, frequent sexual offenses in online video games hampered them from actively participating. Thirdly, women working in the video game industry have been constantly segregated. These three consequences are the byproducts of the male-dominated industry structure and misrepresentation.

Games that feature sexualized characters turn female players away. Because of the sexist and sexualized depictions of women in video games that encourage the objectification of female gamers and may result in unwanted attention from male players, female gamers may avoid competitive gaming [16]. A study has noted that fighting games feature the most sexualized female characters, compared to other genres analyzed in the study [17]. In the same study, role-playing games are ranked second to last for sexualization. Women prefer to play games with less sexualized characters, and according to the study, they play role-playing games more than any other genres. This indicates women players tend to select games that feature comparatively less sexualization on female characters, proving that the sexist content may reinforce the effect of discouraging women from playing video games [17].

Misogyny and sexual harassment in online video games discourages women from participating. Anonymous public engagement may result in a disinhibition effect that allows online users to detach themselves from their anonymous online behaviors and therefore perform discrimination and animosity towards women [16]. As men usually outnumber women in networked video games and masculine behavior is constantly rewarded, this may allow men to display social dominance in the virtual world in a way they can't in the physical world [9]. Websites like “Fat, Ugly or Slutty” and “Not in the Kitchen Anymore” invite players to record sexual and other harassment by posting it online, these documentations show how women are constantly and systematically harassed while playing games, and how often that harassment is often violent verbal sexual assault [18]. This misogyny and its manifestation may drive women away from many networked games or force them into passive participation rather than active involvement [9].

Gender segregation also happens in the video game industry. Within the industry, both vertical and horizontal segregation occur [8]. Women in the industry are often concentrated in traditionally “feminine” jobs such as marketing and administration. They are underrepresented in core creative and development positions such as programmers, designers, and artists [5]. Women’s segregation into certain positions and/or levels might prevent women from influencing the games created and for whom they are created [8]. Toxic culture prevails due to the lack of women in managerial positions. In the game development company Riot Games, some have described a misogynistic “bro culture” where women are talked over and kept out of leadership positions as a result of women only constituting 20% of the workforce [8]. Gendered work practices discourage women from joining and staying in the sector.

5.Rise of Female Voices

Despite the many flaws in the industry, the future is bright for women workers, players, and characters. Although there are far fewer female developers (30% in 2022) compared to male (61% in 2022), the number of female developers working in the video game industry has never been larger, compared to a mere 22% in 2014 [7]. The distribution of female gamers has also been increasing from 38% in 2006 to almost half at 48% in 2021 [6]. The closing of the gender gap is evidence of the growing importance of female voices; hence, it is reasonable to anticipate that women will acquire a greater influence in the video game industry.

As more female developers joined the workforce, the industry becomes more aware of gender equality and proper presentation. Recent feminist discussions, such as “#1reasonwhy,” have raised attention to the underrepresentation of women in professional roles within the industry, in addition to the sexualization and stereotyping of female characters in video games [17]. Female portrayal is becoming more nuanced and deliberate. Some types of improper representation such as benign sexism has been diminishing [19]. Research shows that the sexualization of female characters has been on the decline since 2006. This reduction is explained by a combination of rising female interest in gaming and intensified criticism of the industry's apparent male dominance [17]. For many game companies, female players are becoming a significant target demographic [20]. This change has forced them to focus greatly on appealing to this rising market.

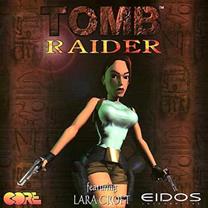

Figure 5: Tomb Raider box art, 1996 [20].

Figure 6: Lara Croft in Tomb Raider reboot (2013), 2015. (Lincoln, R.A.) [20].

The reinventing of game series Tomb Raider exhibits the industry’s awareness towards fixing the sexualized narratives in games. During the old series released between 1996 and 2008, Lara Croft is often seen as a product to satisfy male gaze. Figure 5 exhibits her body in the old series, which is idealized and sexualized with a disproportioned breast and small waist, and the third-person camera position enables the player (who is often a man) to continuously see Lara’s body in full view from behind [20]. The 2013 reboot of the Tomb Raider series reinvented Lara Croft. She has evolved from a flat, two-dimensional character to a multidimensional, emotional personality [20]. Figure 6 shows that her body becomes slim and athletic, and her emotional and physical growth takes place throughout the game [21]. As the video game industry has become aware of gender representation, Lara Croft has transformed into a more realistic character.

6.Conclusion

The male-dominated establishment of the video game industry laid the foundation of its male-centric approaches, in which sexualization, idealized gender representation, women’s lack of agency and their subordinance are utilized to satisfy the desires of the male core consumers. In this case, women have been excluded from the industry at the very beginning. They are portrayed as the entertainment object for the male players. This discourages women from participating in both video games and the video game industry. Due to the increasing number of female voices in the industry, developers have been portraying female characters with more accurate representations to appeal to the female audience base and achieve gender equality goals. It is likely that future video games could escape the long-established masculine norm. This research does not analyze player perceptions of the newly published games that put gender equality as their focus, given the novelty and rarity of these games. Future research could focus on female players’ opinions and their perceived improvements to these games.

Acknowledgement

I would like to express my sincere appreciation to Dr. Yunze Zhao, and Teaching Assistant Xi Luo who have supported me in completing this thesis. I am also grateful to my family, partner, and friends for motivating and supporting me. Lastly, I’d like to mention Dr. Michael Shetina for teaching me the knowledge of writing a scholarly essay.

References

[1]. Clement, J. (2022, November 24). Video games industry in the U.S. 2022. Statista. Retrieved December 19, 2022, from https://www.statista.com/statistics/246892/value-of-the-video-game-market-in-the-us/

[2]. Bailey, E. N., Miyata, K., & Yoshida, T. (2021). Gender Composition of Teams and Studios in Video Game Development. Games and Culture, 16(1), 42–64. https://doi.org/10.1177/1555412019868381

[3]. Behm-Morawitz, E., & Mastro, D. (2009). The effects of the sexualization of female video game characters on gender stereotyping and female self-concept. Sex Roles, 61(11-12), 808–823. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-009-9683-8

[4]. Tompkins, J. E., & Martins, N. (2022). Masculine Pleasures as Normalized Practices: Character Design in the Video Game Industry. Games and Culture, 17(3), 399–420. https://doi.org/10.1177/15554120211034760

[5]. Prescott, J., & Bogg, J. (2011). Segregation in a Male-Dominated Industry: Women Working in the Computer Games Industry. International Journal of Gender, Science and Technology, 3(1). Retrieved from https://genderandset.open.ac.uk/index.php/genderandset/article/view/122

[6]. Clement, J. (2022, October 20). Distribution of video gamers in the United States from 2006 to 2022, by gender. Statista. Retrieved December 17, 2022, from https://www.statista.com/statistics/232383/gender-split-of-us-computer-and-video-gamers/

[7]. Clement, J. (2022, September 2). Distribution of game developers worldwide from 2014 to 2021, by gender. Statista. Retrieved December 17, 2022, from https://www.statista.com/statistics/453634/game-developer-gender-distribution-worldwide/

[8]. Prescott, J., & Boggs, J. (2014). Gender divide and the computer game industry. Information Science Reference.

[9]. Fox, J., & Tang, W. Y. (2014). Sexism in online video games: The role of conformity to masculine norms and social dominance orientation. Computers in Human Behavior, 33, 314-320. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2013.07.014

[10]. Carleton, S. (2018, May 7). Sex, lies, and video games: Shelby Carleton: TEDxUAlberta. YouTube. Retrieved December 18, 2022, from Sex, Lies, and Video Games | Shelby Carleton | TEDxUAlberta

[11]. Image source: https://static.wikia.nocookie.net/mkwikia/images/1/13/Jade2011.jpg/revision/latest?cb=20110303214255

[12]. Image source: https://static.wikia.nocookie.net/mkwikia/images/e/e1/250px-Scorpion_render_by_wildboyz.png/revision/latest?cb=20131106042322

[13]. Image source: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mx5DKbeV79o&ab_channel=LaweressR

[14]. Burgess, M. C., Stermer, S. P., & Burgess, S. R. (2007). Sex, lies, and video games: The portrayal of male and female characters on video game covers. Sex Roles, 57(5-6), 419–433. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-007-9250-0

[15]. Gestos, M., Smith-Merry, J., etc. (2018). Representation of women in video games: A systematic review of literature in consideration of adult female wellbeing. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 21(9), 535–541.

[16]. Ruvalcaba, O., Shulze, J., Kim, A., Berzenski, S. R., & Otten, M. P. (2018). Women’s Experiences in eSports: Gendered Differences in Peer and Spectator Feedback During Competitive Video Game Play. Journal of Sport and Social Issues, 42(4), 295–311. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193723518773287

[17]. Lynch, T., Tompkins, J. E., van Driel, I. I., & Fritz, N. (2016). Sexy, strong, and secondary: A content analysis of female characters in video games across 31 years. Journal of Communication, 66(4), 564–584.

[18]. Jenson, J., & de Castell, S. (2013). Tipping Points: Marginality, Misogyny and Videogames. Journal of Curriculum Theorizing, 29.

[19]. Perreault, M. F., Perreault, G., & Suarez, A. (2022). What Does it Mean to be a Female Character in “Indie” Game Storytelling? Narrative Framing and Humanization in Independently Developed Video Games. Games and Culture, 17(2), 244–261. https://doi.org/10.1177/15554120211026279

[20]. Engelbrecht, J. (2020). The New Lara Phenomenon: A Postfeminist Analysis of Rise of the Tomb Raider. The International Journal of Computer Game Research, 20(3). Retrieved December 19, 2022, from http://gamestudies.org/2003/articles/engelbrecht.

[21]. MacCallum-Stewart, E. (2014). “Take That, Bitches!” Refiguring Lara Croft in Feminist Game Narratives. The International Journal of Computer Game Research, 14(2). Retrieved December 19, 2022, from http://www.gamestudies.org/1402/articles/maccallumstewart.

Cite this article

Pan,R. (2023). Video Games and Gender Equality: How Has Video Gaming Become a Men’s Privilege?. Communications in Humanities Research,6,37-44.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the International Conference on Social Psychology and Humanity Studies

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Clement, J. (2022, November 24). Video games industry in the U.S. 2022. Statista. Retrieved December 19, 2022, from https://www.statista.com/statistics/246892/value-of-the-video-game-market-in-the-us/

[2]. Bailey, E. N., Miyata, K., & Yoshida, T. (2021). Gender Composition of Teams and Studios in Video Game Development. Games and Culture, 16(1), 42–64. https://doi.org/10.1177/1555412019868381

[3]. Behm-Morawitz, E., & Mastro, D. (2009). The effects of the sexualization of female video game characters on gender stereotyping and female self-concept. Sex Roles, 61(11-12), 808–823. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-009-9683-8

[4]. Tompkins, J. E., & Martins, N. (2022). Masculine Pleasures as Normalized Practices: Character Design in the Video Game Industry. Games and Culture, 17(3), 399–420. https://doi.org/10.1177/15554120211034760

[5]. Prescott, J., & Bogg, J. (2011). Segregation in a Male-Dominated Industry: Women Working in the Computer Games Industry. International Journal of Gender, Science and Technology, 3(1). Retrieved from https://genderandset.open.ac.uk/index.php/genderandset/article/view/122

[6]. Clement, J. (2022, October 20). Distribution of video gamers in the United States from 2006 to 2022, by gender. Statista. Retrieved December 17, 2022, from https://www.statista.com/statistics/232383/gender-split-of-us-computer-and-video-gamers/

[7]. Clement, J. (2022, September 2). Distribution of game developers worldwide from 2014 to 2021, by gender. Statista. Retrieved December 17, 2022, from https://www.statista.com/statistics/453634/game-developer-gender-distribution-worldwide/

[8]. Prescott, J., & Boggs, J. (2014). Gender divide and the computer game industry. Information Science Reference.

[9]. Fox, J., & Tang, W. Y. (2014). Sexism in online video games: The role of conformity to masculine norms and social dominance orientation. Computers in Human Behavior, 33, 314-320. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2013.07.014

[10]. Carleton, S. (2018, May 7). Sex, lies, and video games: Shelby Carleton: TEDxUAlberta. YouTube. Retrieved December 18, 2022, from Sex, Lies, and Video Games | Shelby Carleton | TEDxUAlberta

[11]. Image source: https://static.wikia.nocookie.net/mkwikia/images/1/13/Jade2011.jpg/revision/latest?cb=20110303214255

[12]. Image source: https://static.wikia.nocookie.net/mkwikia/images/e/e1/250px-Scorpion_render_by_wildboyz.png/revision/latest?cb=20131106042322

[13]. Image source: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mx5DKbeV79o&ab_channel=LaweressR

[14]. Burgess, M. C., Stermer, S. P., & Burgess, S. R. (2007). Sex, lies, and video games: The portrayal of male and female characters on video game covers. Sex Roles, 57(5-6), 419–433. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-007-9250-0

[15]. Gestos, M., Smith-Merry, J., etc. (2018). Representation of women in video games: A systematic review of literature in consideration of adult female wellbeing. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 21(9), 535–541.

[16]. Ruvalcaba, O., Shulze, J., Kim, A., Berzenski, S. R., & Otten, M. P. (2018). Women’s Experiences in eSports: Gendered Differences in Peer and Spectator Feedback During Competitive Video Game Play. Journal of Sport and Social Issues, 42(4), 295–311. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193723518773287

[17]. Lynch, T., Tompkins, J. E., van Driel, I. I., & Fritz, N. (2016). Sexy, strong, and secondary: A content analysis of female characters in video games across 31 years. Journal of Communication, 66(4), 564–584.

[18]. Jenson, J., & de Castell, S. (2013). Tipping Points: Marginality, Misogyny and Videogames. Journal of Curriculum Theorizing, 29.

[19]. Perreault, M. F., Perreault, G., & Suarez, A. (2022). What Does it Mean to be a Female Character in “Indie” Game Storytelling? Narrative Framing and Humanization in Independently Developed Video Games. Games and Culture, 17(2), 244–261. https://doi.org/10.1177/15554120211026279

[20]. Engelbrecht, J. (2020). The New Lara Phenomenon: A Postfeminist Analysis of Rise of the Tomb Raider. The International Journal of Computer Game Research, 20(3). Retrieved December 19, 2022, from http://gamestudies.org/2003/articles/engelbrecht.

[21]. MacCallum-Stewart, E. (2014). “Take That, Bitches!” Refiguring Lara Croft in Feminist Game Narratives. The International Journal of Computer Game Research, 14(2). Retrieved December 19, 2022, from http://www.gamestudies.org/1402/articles/maccallumstewart.