1.Introduction

In the Jiangyong county of Hunan province exists a script created by and circulated within women – Nüshu. The Chinese word, Nüshu, can be translated as ‘Women’s script” in English, signifying the strictly female-exclusive nature of the language. This script was mainly circulated in the local female population of the county.

The first academic publication on Nüshu was published by Gong Zhebing in 1983 [1]. It mainly encompasses of a detailed description and analysis of the script. This publication has sparked the interests of many linguists and further research into the unique script. Further, Gong published six volumes of Nüshu monographs and over forty academic research articles, introducing Nüshu to the international stage.

The unique literary scripts can reveal significant insight into the conventional customs of women, which enables a more thorough understanding of the societal values and situation from various chronological periods. Scholars have various interpretations regarding the existence of Nüshu; however, the academic community still have not reached a consensus on the topic, and interpretations largely vary. The most widely accepted interpretation is that Nüshu has the primary usage for expressing sentiment and grief of women. This study analyzes existing Nüshu scripts and various sociocultural factors that contribute to the development of Nüshu and examine their primary purposes and impacts.

2.Case Description

2.1.Nüshu Features

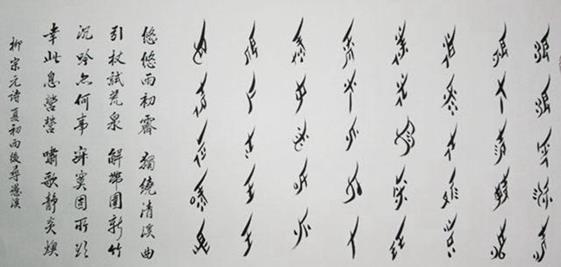

Figure 1: Nüshu Writing Portrayal on the right side [2].

Nüshu characters portray a particular form of feminine. From the shape of the characters, the font of Nüshu tends to come in the shape of a long, italic rhombus, which can be seen in Figure 1 [2]. To be more specific, the upper right corner of each character is the highest point or the starting stroke of a character.

Contrastingly, the lower left corner of the character is where the is the lowest point and where character ends. The intuitive impression of Nüshu is its utilization of the longitudinal perspective, as the font is slanted and slender, strokes are delicate and light, and neat and tight. Moreover, the horizontal is width of the characters are restrained, making it even more significant as this allows a sense of balance in the tilt angle, and a natural flow and simplicity.

Figure 2: Nüshu calligraphy in different font [2].

There are actually only three basic strokes in Nüshu: round point, circle and curved line. Compared with the strokes of square Hanzi characters, the curved strokes of Nüshu are very distinct. For example, the curvature in writing can either be thick or thin, and the curved lines can be long or short, and with numerous variations. The majority out of all the constituent parts of a single Nüshu character are arcs. Unlike Hanzi, there are no distinctions such as a horizontal or vertical strokes in Nüshu. Further, the circle stroke is unique to the Nüshu script, and is often paired with two curved lines, forming an oval with the top and bottom not closed, shaped like a rhombus. In addition, the supposed ‘folding’ strokes depicted in the middle character in Figure 2 are also made by the intersection of two curved lines [2].

2.2.Nüshu Circulation

Nüshu circulation in history differed significantly from the circulation today. Nüshu is passed down amongst women in the Jiangyong. More importantly, its creation, use, and transmission are from the establishment and circulation within ordinary peasant women. It has an implied, unwritten rule of circulation, “passing down to women but not to men, old to young, and mother to daughter.” The transmission of Nüshu is a spontaneous act of without a system.

There are two types of Nüshu generational transmission: natural and unnatural transmission. The historical method mainly resulted in natural inheritors, whereas the premodern and modern period produced unnatural inheritors. Natural inheritors are usually illiterate, and thus not influenced by the writing of Hanzi characters. Additionally, their inheritance of Nüshu is entirely the of the female’s spontaneous participation in the learning of this activity. Methods of transmission encompass a variety of methods, including orally through activities such as family, relatives, friends, elders or cultural customs of Nüshu. The transmitter sings orally, and the ‘student’ listens and imitates the reproduction. Through listening and practice, many eventually recognize the entire system of Nüshu and thus are able to pass on this to future generations through the same method. From the 1980s and on, Nüshu received increased attention from local residents and scholars, and most of them are unnatural inheritors. The three most influential unnatural inheritors include Yi Nianhua (1907-1991), Gao Yinxian (1902-1990), and Yang Huanyi (1905-2004) [3].

3.The Purposes of Nüshu

Nüshu’s primary purpose was to unite the common characteristic of shared women’s disempowerment to build sense of community for expression of powerlessness and constraints.

3.1.Social and Cultural Influences

Societal norms in ancient China were mainly centered around androcentric beliefs. This focal point shaped different aspects such as social hierarchy, cultural practices and beliefs.

Nüshu is used only by the women of the Jiangyong region. Generally speaking, the narrative poems and ballads recorded in Nüshu are not the women’s original creations, but come from the popular folk oral heritage. Nevertheless, since finding their way into Nüshu they have undergone alteration and adaptation at the hands of the female writers, and have thus taken on a distinctive coloring. The works now show a keen perception of the subtle secrets of the inner spiritual world of women.

In this section, primary sources of Nüshu scripts will be analyzed. It is important to note that the majority of scripts in Nüshu is translated from popular folk stories told in Hanzi. However, they are modified from the female perspective, and thus may have altered some segments of the story of potentially the message conveyed. Sources will be interpreted using a sociocultural perspective that aims to convey the message that Nüshu was more than a form a sentimental expression, rather, it acted as a method to build a sense of community that united the shared characteristic of women in the Jiangyong community.

The story Flower Girl, is a folktale that has been documented in Nüshu script:

“It seems I am cursed by fate, that I must be a flower girl, cutting and selling flowers on the street, to earn money for our livelihood, I would rather die by sword than losing my virtue to accompany his excellency. If I were to give in and enter this dirty affair, I would turn into a beast with hair and horns.”

The main character in this tale, the flower girl, could also be regarded as Lady Zhang. In this tale the emperor’s father-in-law attempts to seduce Lady Zhang. However, she explicitly rejects the emperor; however, this only leaves her to be threatened by the aristocratic authority and ultimately murdered for her acts [4]. The documentation of the second section of the tale was not translated into Nüshu, but was analyzed in the form of Hanzi. This portion transitions to introduce the protagonist Lord Bao, in which he is responsible for punishing the eunuch and the emperor’s father-in-law. In technical terms, this tale employs the ancient Greek theatre technique – deux ex machina, which is the use of an artificial device or contrived solution to solve a difficult situation, usually introduced suddenly and unexpectedly. In this case, the contrived solution would be Lord Bao. The moral lesson of this folktale is considerably apparent: The flower girl, or Lady Zhang, represents the paragon of the female virtue and Lord Bao is the model for the standard aristocratic behavior [4].

The folktale Flower Girl begins by portraying kelian, or the sentimentality, which is a prominent state of being for women during ancient China. Then, the story transitioned to the expected behavior of Lady Zhang, which is deliberately told to teach the lesson that women should follow her acts. It is important to know that her actions differ from the typical cultural expectations of women, which is that women are born to be subservient in comparison to men. Thus, Lord Bao was introduced on the basis of playing the role of a protagonist and resolve the entire issue. This could potentially be a reason as to the exclusion of the second portion of Flower Girl from the Nüshu scripts. Further, Lady Zhang’s actions were shaped as if the nature of women was to be bold and to stand up for the oneself when one’s rights are violated, which significantly differs from the prevalent belief in the ancient Chinse society that women should be passive, reserved, and subservient. Therefore, comparing in the message conveyed by the folktale modified through a female’s lens with the lesson of the original folktale, it is reasonable to argue that Nüshu served more purposes than to express sentiment and grief.

This then begs the question that how does conveying the modified lesson contribute to building a communal identity within the women of the Jiangyong county. Foremost, it is important to note the degree of subjectivity in the Nüshu scripts. Despite being told in the third-person perspective, the folktales still build a sense of relatability and potentially appeal to the sense of sympathy and sorrow in women. This allows women to grasp a sense of purification or cleansing of the spirit through the emotions of pity as a witness to a tragedy, or in short, catharsis. The process of catharsis then triggers the transformation of the mental state of isolation to a sense of relatability and belonging with others. In simpler terms, through the shared characteristic of grief that is relatable to many women in the community, Nüshu scripts are able to trigger the process of catharsis that contributes to the discussion of these scripts, and thereby establishing a sense of belonging in the women of Jiangyong county.

The story of the Imperial Concubine also reflects this purpose of the Nüshu:

“I have lived in the Palace for seven years. Over seven years, only three nights have I accompanied my majesty. Otherwise, I do nothing.... When will such a life be ended, and when will I die from distress? . . . My dear family, please keep this in mind: If you have any daughter as beautiful as a flower, you should never send her to the Palace. How bitter and miserable it is, I would rather be thrown into the Yangzi River.”

Hu Yuxiu, the female main character of this Nüshu translated script, wished to send messages home as a way to commute and relieve her pain and distress in the imperial city [5]. Regardless, being the emperor’s concubine forbade her from doing so. The narrative continues on to express Hu’s exhort, which is evident, is that women should beware of becoming the emperor’s concubine or wife, as it simply brings incessant boredom, pain, and distress. Undeniably, there is the clear illustration of the expression of sentiment and grief, however more importantly, lies the advice that Hu Yuxiu aims to convey. In this story, sentiment and the message combined also yields the catharsis effect discussed in the first example.

Likewise, a selection from the popular folk narrative Liang Shanbo and Zhu Yingtai also conveys a similar message:

Zhu: “People who have good luck have large breasts, but people without good luck have no breasts. A man with large breasts is bound to achieve high office, but a woman with large breasts will lead a lonely life.”

The culturally established gender hierarchy is undermined by Yingtai’s articulations of these physical distinctions, which portray men as much as an ignorant being and prone to subjugation by a competent female. Furthermore, it appears that she values androgyny because she describes huge breasts—a physical characteristic of femininity—as a sign affliction for women but of fortune for the male counterpart [6].

This narrative reveals a hint of bitterness, while still taking on the main purpose of conveying advice to women. Though its expressive of sentiment, this narrative simultaneously provides women with a feeling of hope, where in the potential future, they would be able to gain opportunities in the society, just like Yingtai.

3.2.Religious Influences

Confucianist values, particularly the beliefs that pertain to women’s virtue, also shape purpose of Nüshu. Core feminine values that are prominent in Nüshu scripts include female chastity, filial piety, and male supremacy. A different selection of the popular folktale Liang Shanbo and Zhu Yingtai these Confucian factors. Yingtai, after a long period of pursuing her studies, thought it was time to return home, since: “If one does not exhaust oneself in filial caring, one cannot be counted as a human being and filial child.”

Yingtai is aware that she will one day resume her duty as a pious daughter who will espouse a male partner of her father’s choosing. Her new identities acquired from her studies, which seem to be from the Confucianist guidelines of the supposed behavior of daughter, wife, or mother, have gave rise to conflicting emotions that she must reconcile. It would be impossible for her to disregard the arranged marriage as the advocated Confucianist behavior is that since they owe their father a duty as a daughter. She is required to adhere to the “rites and righteousness” laws as a Confucian pupil, meaning she must relinquish her personal affections for Shanbo, the male protagonist in the folktale [6]. Therefore, these intertwining conflicts between religious expectations, gender norms, and personal aspirations lead to the internal conflicts that Yingtai experiences.

Yingtai, who seamlessly blends traditional and revolutionary personalities, is the epitome as to how reflection and refraction concur [7]. In addition, Yingtai demonstrates the complexity in her character: “being adventurous but filial, rebellious but virtuous, learned but not pedantic” [7]. Yingtai’s persona and action speaks to many Jiangyong women’s moral attitudes regarding romantic relationships – admirable, but unrealistic. Many of what Yingtai undergoes are similar, if not exactly identical, to the experience of a typical female who situates in ancient China. This was mainly due to the fact that women’s rights were extremely limited and the continued influence of Confucianist expectations. Therefore, this evokes a feeling of bitterness and sympathy towards Yingtai, while simultaneously building a sense of relatability aspects of their own life, specifically, arranged marriage.

Aside from the Yingtai and Shanbo selection, a Nüshu translated tale, On Remarriage and Chasity, reflects similar religious influence:

“A man without a wife has no treasure at home. A woman without a husband has no idea in mind. Drinking a cup of good wine, the whole face is in blush; Blooming with beautiful flowers, the whole tree is in redness.”

The moral of On Marriage and Chasity is that women require a husband just as if a family needs a mother. This can be easily determined by Confucian ideologies decree that women should occupy themselves with domestic sector duties. Moreover, beliefs further dictate then even a widow potentially choosing to leave her deceased husband is still a violation of the moral code, as it is believed that this act demonstrates her unfulfilled obligated duty towards her husband’s parents and prohibits the continued transfer of her husband’s bloodline.

The folktale, The Story of Qiu Hu, also reflects the influence of Confucian ideologies on shaping the content of Nüshu scripts: “Wherever and whenever you go, I will always follow, married to you, I am forever at your disposal, your devotion to studies is the nature and soul of a man.” The development of The Story of Qiu Hu reflects the significant development of the female rebellious side of nature that directly contradicts the root Confucian feudal ideals. Though only spread in Nüshu amongst women, it is evident that the Confucian “three obedience” and “four virtues” that coded women’s familial behaviors were questioned in this script, as the main character Cunse, spoke up against the actions of her alleged superior husband. Cunse’s image The Story of Qiu He portrays is unequivocally conveying feminine energy with self-reliance and stamina, which corresponds effectively with the rebellious side of Jiangyong women.

3.3.General Comparison

They were not allowed to publicly express grievances and hardships encountered in daily duties, as it was a social norm where men were those responsible for the alleged difficult occupations, and therefore, women had the less the complain about.

All of the previously mentioned Nüshu translated scripts in both the sociocultural and religious category reveal an apparent intertextuality – the characteristic of discovering community belonging through sentiment and grief, or the challenging of traditional ideologies. Furthermore, considering that many of these scripts are burnt after the author dies, this implies that these scripts are unlikely to serve the purpose of passing on the moral purpose to future generation, but to seek use these moral lessons to effectively communicate with other Jiangyong women for sake of finding a sense of belonging within community and, for an emotional expression, serves the purpose for women to collectively “walk out of the shadows.”

4.Nüshu in History

In this portion of the paper, the impact of Nüshu will be analyzed using two technical terms: Centrifugal force and Centripetal force. In this case, centrifugal force holds the definition of forces that segregates or “pushes” people, beliefs, or events away from the center point of an area [8]. Contrastingly, Centripetal force is defined as a force or attitude has the tendency to unite people or beliefs together. Throughout history, Nüshu has acted as both a centrifugal and centripetal force in various aspects.

4.1.Centrifugal Force

Nüshu has isolated Jiangyong County from rest of the nearby regions. In Chinese history, only villages located in the Jiangyong County were influenced Nüshu, which made this characteristic a distinct feature that separated this region from the rest of Hunan province. Furthermore, the female exclusive nature of Nüshu has further impacted the connectivity within the county itself. As mentioned in the previous sections, Nüshu was strictly circulated within the female community. This could potentially contribute to further gender segregation within individual villages in the Jiangyong county, and thereby could be regarded as a centrifugal force that increasingly segregated the societal aspect. As evidently portrayed in history, many of the original Nüshu scripts were incinerated by Red Guards during the Chinese Cultural Revolution [9], as they were thought to be private and personal, and thus were almost completely eliminated. In essence, the presence of Nüshu is vastly different from the sociocultural conditions that it was placed in. Therefore, Nüshu had the potential to act as a centrifugal force in local, regional, and national terms.

4.2.Centripetal Force

Even though it acted as a centrifugal force in some aspects, Nüshu was able to effectuate centripetal impacts in numerous fields. Arguably, the most significant centripetal factor of Nüshu was that it brought together deep connections within female communities. This unique script enabled women to freely discuss and share personal stories with each other without being violated of their privacy. This effect was amplified by the shared Nüshu narratives themselves, which can be attributed to the common sentimental characteristic present in the majority of the analyzed scripts [10]. To be more specific, in section three of this paper, the interpreted scripts were linked in a certain way or degree. The Flower Girl, the Imperial Concubine, and the first selection of Yingtai were all folktales that stemmed from the vulnerability of women in the sociocultural aspect. The following through were stories that all reflected the pressure Confucianist beliefs exerted upon women from a different perspective [11]. Nevertheless, all the scripts analyzed in this paper, and the majority of the Nüshu scripts discovered all shared these similar sentimental characteristics. This phenomenon leads to the claim that Nüshu enabled the intertwined network of Jiangyong women to cultivate relationships with each other and build a sense of belonging within the entire Jiangyong community. This centripetal factor explains the reason why Nüshu has been regarded as a secret code for women in history.

It is human nature to find acceptance and sense of belonging through common characteristics, which would be one of the main purposes of Nüshu. Indeed, Nüshu is built on the foundation of the primary expression of grief and sentimentality, which prevents the circulation of this to a wide extent as the narratives were mainly personal anecdotes. However, this common characteristic was able to create significant impact amongst the female community themselves because it provided many illiterate women to acquire the opportunity to share similar life experiences. Nüshu ultimately result in the creation of a deeply interconnected and strong community, and thus, could be regarded as being a substantial centripetal rather than a centrifugal force.

4.3.Nüshu Today

Akin to its centripetal factor in the historical eras, Nüshu today continue to forge a sense of unity within the entire female community of China [12]. Today, the increased communicational connectivity facilitated the diffusion of Nüshu, attracting a large group of linguists and calligraphists across regions of China. They further promoted the awareness of the existence of such a distinct language that originated in China, fueling a sense of appreciation for the rebellious community of women in ancient China. The evoked sensations further transform into the acquaintance of national pride within the entire Chinese community [13]. The mere existence of Nüshu itself is able to exert the impact of building national identity and cultural pride within the Chinese community and the global female community, and much more [14]. In essence, considering the value it possesses in modern day society, the potential Nüshu has as a centripetal force is momentous.

5.Conclusion

The paper focuses on the interpretation of the purpose of Nüshu through the analysis of translated primary Nüshu folktales, specifically the shared characteristics within them. It also looks into how these features contributed to a greater communal purpose. Further, the centrifugal and centripetal factors of Nüshu were also examined while accounting for the previously derived purpose from the dissection of Nüshu folktales. Despite having distinct sensations and morals, the entirety of the analyzed scripts was expressed through sociocultural or Confucianist anchored aspects that ultimately portrayed sentiment, rebel, and femininity. This characteristic fostered a sense of acceptance and community amongst the Jiangyong female community, and could be regarded as one of the most significant purposes of Nüshu. Through the existence of Nüshu itself and the previously derived purpose, it was fair to derive the conclusion that the centripetal features were considerably more substantial than the centrifugal features of Nüshu.

By analyzing the purpose and subsequent impacts Nüshu yields, this paper suggests that, in addition to recognizing the expression of emotion and morals of the scripts, researchers should also take into consideration the purposes of such a feature and not to overlook the implications that shared characteristics of Nüshu could establish in terms of communal connectivity. In a nutshell, the existence of Nüshu is a valuable channel to broadening our understanding of the development of Chinese history, a unique form of feminism, and much from a unique aspect, therefore, it is important to consider Nüshu from every aspect possible.

References

[1]. Liu, Y. (2018, April 14). Interview with Gong Zhebing, the first person to discover Chinese women’s writing. Retrieved February 17, 2023, http://www.hubeitoday.com.cn/post/43/76273.

[2]. Guo, Q. (2021, April 8). The Hundred-Style Calligraphy - The creation, development, and current situation of Nüshu. Retrieved February 17, 2023, from http://www.360doc.com/content/21/0408/10/36333732_971161081.shtml.

[3]. Gov. Yongzhou, yzcity. (2021, November 4). Nüshu culture. Retrieved February 17,2023, http://www.yzcity.gov.cn/cnyz/nswh/202111/96d9eeef3842451db02b4edf1521437a.shtml.

[4]. Shouhua, L., & Xiaoshen, H. (1994). Folk Narrative Literature in Chinese Nüshu: An Amazing New Discovery. Asian Folklore Studies, 53(2), 307–318. https://doi.org/10.2307/1178648.

[5]. Liu, F.-W. (2004). From Being to Becoming: Nüshu and Sentiments in a Chinese Rural Community. American Ethnologist, 31(3), 422–439. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3805367.

[6]. Liu, F.-W. (2001). The Confrontation between Fidelity and Fertility: Nüshu, Nüge, and Peasant Women’s Conceptions of Widowhood in Jiangyong County, Hunan Province, China. The Journal of Asian Studies, 60(4), 1051–1084. https://doi.org/10.2307/2700020.

[7]. Liu, F. (2010). Narrative, Genre, and Contextuality: The “Nüshu”-Transcribed Liang-Zhu Ballad in Rural South China. Asian Ethnology, 69(2), 241–264. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40961325.

[8]. Oxford, U. (2007). Centrifugal Force. Oxford Reference. Retrieved February 17, 2023, https://www.oxfordreference.com/display/10.1093/oi/authority.20110803095558777;js sionid=2F2053D4EEF4FA4CF239837A85909AFE.

[9]. Orie, E. (1999, May). Review Chûgoku no onnamoji [Chinese women’s script]. Intersections. Retrieved February 17, 2023, http://intersections.anu.edu.au/issue2/endoreview.html.

[10]. Yan, H..(2021). Jiangyong “Women’s Script” in the Era of ICH: Channels of Development and Transmission. Asian Ethnology, 80(2), 367–390. https://www.jstor.org/stable/486341.

[11]. McLaren, A. (1996). Women’s Voices and Textuality: Chastity and Abduction in Chinese Nüshu Writing. Modern China, 22(4), 382–416. http://www.jstor.org/stable/189302.

[12]. Chen, X. (2018, February 23). Nüshu: The “book of tears”, Chasing the Sun. UNESCO. Retrieved February 17, 2023, https://zh.unesco.org/courier/2018-1/nu-shu-zhui-zhu-yang-guang-yan-lei-zhi-shu.

[13]. Leung, C. K. K. (2003). Women Who Found A Way Creating a Women’s Language. Off Our Backs, 33(11/12), 40–43. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20837958.

[14]. We. (2023). The world’s only female text comes from a small town in Hunan. Retrieved February 17, 2023, from https://m.weibo.cn/status/4853423738978337?wm=3333_2001&from=10CC393010&sourcetype=weixin.

Cite this article

Wen,Y. (2023). The Origins of Nüshu and Its Historical Development. Communications in Humanities Research,6,110-118.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the International Conference on Social Psychology and Humanity Studies

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Liu, Y. (2018, April 14). Interview with Gong Zhebing, the first person to discover Chinese women’s writing. Retrieved February 17, 2023, http://www.hubeitoday.com.cn/post/43/76273.

[2]. Guo, Q. (2021, April 8). The Hundred-Style Calligraphy - The creation, development, and current situation of Nüshu. Retrieved February 17, 2023, from http://www.360doc.com/content/21/0408/10/36333732_971161081.shtml.

[3]. Gov. Yongzhou, yzcity. (2021, November 4). Nüshu culture. Retrieved February 17,2023, http://www.yzcity.gov.cn/cnyz/nswh/202111/96d9eeef3842451db02b4edf1521437a.shtml.

[4]. Shouhua, L., & Xiaoshen, H. (1994). Folk Narrative Literature in Chinese Nüshu: An Amazing New Discovery. Asian Folklore Studies, 53(2), 307–318. https://doi.org/10.2307/1178648.

[5]. Liu, F.-W. (2004). From Being to Becoming: Nüshu and Sentiments in a Chinese Rural Community. American Ethnologist, 31(3), 422–439. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3805367.

[6]. Liu, F.-W. (2001). The Confrontation between Fidelity and Fertility: Nüshu, Nüge, and Peasant Women’s Conceptions of Widowhood in Jiangyong County, Hunan Province, China. The Journal of Asian Studies, 60(4), 1051–1084. https://doi.org/10.2307/2700020.

[7]. Liu, F. (2010). Narrative, Genre, and Contextuality: The “Nüshu”-Transcribed Liang-Zhu Ballad in Rural South China. Asian Ethnology, 69(2), 241–264. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40961325.

[8]. Oxford, U. (2007). Centrifugal Force. Oxford Reference. Retrieved February 17, 2023, https://www.oxfordreference.com/display/10.1093/oi/authority.20110803095558777;js sionid=2F2053D4EEF4FA4CF239837A85909AFE.

[9]. Orie, E. (1999, May). Review Chûgoku no onnamoji [Chinese women’s script]. Intersections. Retrieved February 17, 2023, http://intersections.anu.edu.au/issue2/endoreview.html.

[10]. Yan, H..(2021). Jiangyong “Women’s Script” in the Era of ICH: Channels of Development and Transmission. Asian Ethnology, 80(2), 367–390. https://www.jstor.org/stable/486341.

[11]. McLaren, A. (1996). Women’s Voices and Textuality: Chastity and Abduction in Chinese Nüshu Writing. Modern China, 22(4), 382–416. http://www.jstor.org/stable/189302.

[12]. Chen, X. (2018, February 23). Nüshu: The “book of tears”, Chasing the Sun. UNESCO. Retrieved February 17, 2023, https://zh.unesco.org/courier/2018-1/nu-shu-zhui-zhu-yang-guang-yan-lei-zhi-shu.

[13]. Leung, C. K. K. (2003). Women Who Found A Way Creating a Women’s Language. Off Our Backs, 33(11/12), 40–43. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20837958.

[14]. We. (2023). The world’s only female text comes from a small town in Hunan. Retrieved February 17, 2023, from https://m.weibo.cn/status/4853423738978337?wm=3333_2001&from=10CC393010&sourcetype=weixin.