1.Introduction

The United Nations Fourth World Conference on Women, held in Beijing in 1995, included “women and the media” as a major area of concern for women’s development, and women’s empowerment has gradually become an important communication objective for the protection of women’s rights worldwide. The subject of empowerment and women’s empowerment is also gaining more and more attention in the academic world.

The concept of empowerment can be traced back to the 1960s and 1970s, which is defined as “the process through which individuals perceive that they control situations,” emphasizing the agency of individuals in actively participating in their environment rather than passively reacting to it [1]. According to the research of Chinese scholar Ding Wei [2], there are various definitions and examination paths concerning empowerment in academia, all of which have the basic characteristic of “dynamic relationality,” starting from the theoretical core of “power” to consider empowerment. Referring to Foucault’s doctrine of power, empowerment is based on the practical processes of people obtaining information, participating in expression, and taking action, which makes “self-empowerment” possible. In the era of mass media, the dissemination of information and the exertion of power are interrelated. The communication scholar Rogers introduced empowerment theory into communication studies and proposed “group empowerment”: empowerment is a dialogic communication process in which the powerless individual communicates with the group, feels the collective power and gains power himself [1]. In this way, empowerment theory seeks to create a responsive community [3].

Recent developments in new communication technologies and digital media platforms have created new ways for women to express their views and demands in the public arena, and have facilitated the formation of women’s communities and collective female empowerment. Year 2017 saw the launch of the #MeToo campaign on social media platforms by American actress Alyssa Milano to resist sexual harassment, which has swept through most countries, including China. “The #MeToo movement, swept through most countries around the world, including China. In the campaign, social media and online platforms have empowered vulnerable groups to have more of a voice and have pushed sexual harassment to become a global conversation. In 2019, Chinese netizen blogger “Yu Nha” blogged about her experience of domestic violence on her Weibo account, garnering responses and solidarity from women with similar experiences and promoting actions by women’s rights protection organizations and the media. And during the 2020 Covid-19 epidemic in China, several female independent bloggers used the hashtags #SeeWomenWorkers and #SisterhoodEpidemicAction to build an alternative discursive framework of female empowerment, making it possible to construct a community of female action [4].

Behind women’s digital resistance is an expansion of discursive space. In China’s long-standing social practice, the traditional perception of the male as the mainstay of the family and the female as the bearer of the offspring has led to a distinction between the status of men and women in the family, with women rarely having the power to make independent physical and reproductive choices, and women’s fertility is rarely spoken of as a private topic. However, with the new media era, Chinese women’s ability to express themselves and communicate has reached an all-time high, and women are beginning to talk openly about the process of childbirth and share their unique feelings about their changing identities. This has become a unique and novel social media phenomenon, with intense discussions between those who pass it on and those who receive it, which has inevitably stimulated an awakening of awareness among the female community. One of the most representative platforms, Bilibili, with its youthful community and interactive video sharing, has attracted female video bloggers aged 25-40 (collectively known as “Uploaders”) to document real-life birth experiences and share up-to-date parenting information to help a wider audience of women understand their bodies, make independent choices about marriage and parenthood, and have healthy gender and parent-child relationships, thereby promoting women’s autonomy and a wider range of rights.

Based on the perspective and methods of communication studies, this research reflects on how media empowers women by exploring how women discuss childbirth on mobile social media platforms, represented by Bilibili, aiming to deepen the understanding of the impact of media on the dissemination of women’s issues, the comeback of women’s autonomy, and the construction of female community. To this end, this study adopts the “empowerment theory” as a framework to investigate the relationship between new media development and women’s reproductive topics, as well as the connection between media empowerment of women and the development of women’s rights, providing new ideas and insights from the perspective of communication to promote social equality and women’s development.

2.Literature Review

2.1.Women’s Empowerment and Motherhood Experience

The humanistic nature of empowerment theory makes it focus on powerless and vulnerable groups, such as the elderly, children, women, and people in the third world. Among them, the observation of women by empowerment theory began with the feminist and black movements of the 1970s [5], and women gradually became aware of and began to resist various injustices in social environments and cultural cognition, making empowerment theory the cornerstone of women’s struggle for liberation and gender equality.

As an important component of women’s empowerment, maternal empowerment further extends the women’s empowerment movement, emphasizing the power and advocacy of women in the process of bearing and nurturing children and acknowledging the positive significance of motherhood as an experiential empowerment for women [6]. American feminist scholar Adrienne Rich defined motherhood as an earned rather than instinctive process, broadening theoretical perspectives and ways of thinking for motherhood research [7]. Canadian maternal studies expert Andrea O’Reilly replaced “motherhood” with maternal practice (mothering), referring to women’s experience as mothers [8].

This shift from motherhood to motherhood experience highlights the gradual formation of a female-defined, female-centered, pluralistic and open postmodern feminine value orientation, which helps women break through patriarchal constraints and practice a new type of maternal empowerment. However, most of the studies on motherhood practices in China focus on nurturing and parenting practices [9], but less on the indispensable experience of motherhood. For the latter, some scholars have focused on the loss of autonomy of pregnant women due to medical gaze during maternity examinations [10], or on the maternity constructed by pregnant women under the reconciliation of tradition, family, and medical technology [11]. Some scholars have else focused on the construction of motherhood autonomy by WeChat parenting groups [12], while others have explored maternity practices in terms of culture and the formation of the pregnant body, the relationship between the pregnant body and the medical system, and the use of maternal empowerment [13].

In the field of research on motherhood and maternal empowerment, the issues of power, oppression, and agency are at the center of the discussion, also in the female gestation stage [13]. However, due to Chinese cultural traditions, the long-existing family planning policies and the health care system, women in China have long been repressed in the process of childbirth [13], and there are few ways and opportunities to express their demands to the outside world and insufficient attention from the media. According to CNKI data, until the last decade, research related to women’s reproductive expression and media use in China has shown a significant upward trend. Therefore, there is still room for exploration of media coverage and disciplinary research on women’s childbearing experiences, both in news production and academic research.

2.2.Women’s Empowerment in New Media

In the wake of advances in communication technology and the popularity of the Internet, domestic and international research has focused on the field of new media empowerment. New media empowerment has mostly taken the form of Cyberactivism, a social movement that uses media and communication technologies to engage in social movements or attempts to change media behaviour and communication policies [14]. The development of digital media platforms that support user-generated content (UGC) has further widened its path, making it possible for more women to speak out in public spaces and spawning a large number of women’s content self-media. In particular, the social phenomenon of women using social media platforms to rebel against the injustices suffered by women and challenge the dominant gender discursive power relations through female narratives has been described by Frances Shaw as “feminist discursive activism [15].” Through media platforms, female communicators produce and disseminate feminist messages, share gendered bodily experiences and emotional experiences, and initiate actions to sustain feminist discourses, giving rise to online feminist discursive communities across geographies, groups and platforms. This has led to an expansion of feminist dialogue, with women using social media as a form of empowerment to make the transition from digital resistance to information sharing to the formation of discursive communities.

In summary, empowerment theory has gradually expanded from women to the special role of mothers, especially in the new media context, where the media has been organically extended to empower women, and the research on women’s reproductive stage also needs to be explored and complemented. Therefore, in the context of the promotion of China’s “three-child policy” and irreversible global aging, from the perspective of empowerment theory, this study focuses on the female’s self-representation in media and community construction through childbirth videos, aiming to provide academic observation and discussion for the media to assume social responsibility and promote social understanding and women’s development.

3.Research Design

3.1.Research Questions

Based on the previous discussion, this study focuses on the following topics from the perspective of female empowerment in social media:

(1) What kinds of childbirth topics and individual experiences do female video Uploaders present in their videos on the Bilibili platform? How do they achieve individual empowerment?

(2) How do audiences on Bilibili provide immediate feedback and emotional exchange through bullet comments? What makes female group empowerment possible?

(3) What is the role of social media in the empowerment process, as represented by the Bilibili platform?

3.2.Research Methodology

This study adopts a combination of qualitative and quantitative research methods, mainly content analysis and discourse analysis.

Content analysis is an objective, systematic and quantitative method of describing the content of discourse with explicit characteristics, aiming to analyze the explicit content of messages in order to explore the implicit social reality of messages [16]. In this study, 38 fertility-related videos and their bullet comments on the Bilibili platform were selected as research subjects, and their video themes and content topics will be coded and classified and analyzed descriptively. Meanwhile, this study uses Python to crawl the bullet comments of the videos, and performs sentiment analysis, word frequency analysis and LDA topic analysis on the cleaned bullet comments data to achieve a deeper understanding of audience feedback.

In addition, in the process of discourse analysis, this study focuses on the important dimensions of discourse practice analysis and social practice analysis in Fairclough’s three-dimensional approach to discourse analysis, focusing on the socio-cultural impact of a particular text in the process of production, circulation and consumption, the constructive function of discourse on individual identity and social relations, and the interaction mechanism between discourse and society and ideology.

3.3.Sample Collection

In this paper, 38 videos related to childbirth on the Bilibili platform were selected as the samples for the case study during the three years from 2020 to 2022 (See Appendix for selection reasons), mainly focusing on the video content and bullet comments. The selection criteria for videos include: (1) video Uploaders should be women of childbearing age between 25-40 years old and have a fan base of 700,000 or more. (2) videos with more than 100,000 views and a video length of more than 5 minutes.

The data used for the study include three categories: first, the tags, titles and profiles of the works provided by the platform; second, the videos provided by the Uloaders; and third, the bullet comments provided by the viewers. The videos were all released after 2020, and the data were collected from the start of video release until December 31, 2022. This study uses Python to crawl the bullet comments of these 38 videos, and used the jieba Chinese word separation toolkit and three deactivated word databases (HIT, Chuan University, and Baidu) to reject the subscripts and complete the corpus cleaning, and got a total of 48,989 valid bullet comments. To ensure the equal weight of each video’s bullet comments, this study used SPSS to sample 1000 bullet comments from each video randomly, and a total of 38,000 bullet comments were extracted as the data set.

4.Data Analysis

4.1.Topic and Content Analysis

After the sample collection, the study first coded and counted the topics and content topics of the 38 videos. The distribution of video themes (Table 1) and content topics (Table 2) is shown below, where the content topics were coded by two coders to summarise the topics covered in the videos, with two levels of topics, psychological (including childbirth intentions and emotions, childbirth cost considerations, identity and relationship changes) and physical (including physical changes and injuries, medical treatment during pregnancy, postnatal breastfeeding and repair).

Table 1: Video theme distribution.

Video Subject |

Number of Videos |

Proportion |

Delivery experience |

23 |

60.53% |

Delivery choice |

9 |

23.68% |

Delivery process |

6 |

15.79% |

Table 2: Video content topic distribution statistics.

| Primary Subject | Sub-Subject | Word Frequency | Proportion | Mental | Fertility intentions and emotions | 44 | 20.09% | Consideration of the cost of childbearing | 16 | 7.31% | Identity perception and relationship changes | 31 | 14.16% | Physical | Physical changes and injuries | 56 | 25.57% | Pregnancy procedures | 41 | 18.72% |

Table 2: (continued).

Postpartum breastfeeding and recovery 31 14.16%

The statistical analysis of video themes and content topics shows that most female Up owners choose to present their post-birth experiences directly in their videos, sharing the changes and injuries their bodies produce, the changes in their sense of identity and social relationships, and their experiences during and after pregnancy. In a small number of videos, Up owners choose to directly present their birth process (Video 7, 11, 18, 19, 27, 35) or express their reluctance to give birth (Video 3, 13).

4.2.Sentiment Analysis

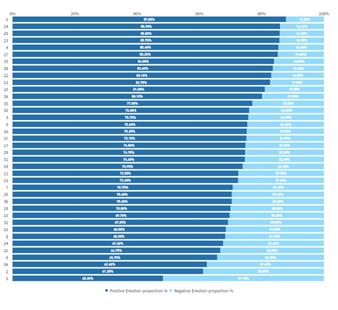

After completing data collection and data preprocessing, this study calls SnowNLP, a TextBlob-based Python library used to process Chinese natural language and perform sentiment analysis, to analyze the sentiment tendency of 38 video bullet comments. The SnowNLP library comes with Chinese positive and negative sentiment training sets, which can realize sentiment analysis, lexical annotation (see Figure 1). In this study, the bullet comments that reflect approval and support are positive emotions, and the bullet comments that express doubt and opposition are negative emotions.

Figure 1: Sentiment analysis of bullet comment texts.

The data results show that the percentage of positive sentiment bullet comments of 38 videos is 74.65% on average, among which 18 videos have a higher-than-average percentage of positive sentiment bullet comments (Video 1, 14, 20, 23, 4, 27, 33, 28, 22, 12, 10, 38, 35, 30, 3, 9, 16, 37), 20 videos have a lower-than-average percentage of positive sentiment bullet comments (Video 17, 29, 31, 19, 11, 13, 7, 26, 36, 18, 15, 32, 25, 8, 24, 21, 6, 34, 2, 5). Overall, the bullet comments showed more positive emotions, reflecting approval and support emotions.

4.3.Word Frequency Analysis

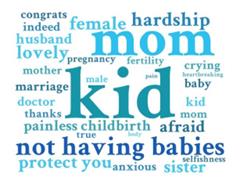

After the sentiment analysis of the bullet comments, this study then divided the 38 video’s bullet comment data into two groups: the 20 videos with a lower-than-average percentage of positive sentiment bullet comments are Group 1, and the 18 videos with a higher-than-average percentage of positive sentiment bullet comments are Group 2. This study then conducted Top20 keyword word frequency statistics for each of the two groups (see Table 3) and plotted the statistics into a word cloud diagram (see Figure 2).

Table 3: Top20 keyword frequency statistics after bullet comment grouping.

Group 1 |

Group 2 |

||||||

Keyword |

Frequency |

Keyword |

Frequency |

Keyword |

Frequency |

Keyword |

Frequency |

kid |

1167 |

husband |

187 |

congrats |

1131 |

come on |

217 |

mom |

622 |

marriage |

176 |

sister |

959 |

breast milk |

196 |

not having babies |

405 |

kid |

175 |

kid |

605 |

hardship |

163 |

hardship |

331 |

doctor |

172 |

lovely |

446 |

thanks |

154 |

female |

309 |

baby |

160 |

mom |

369 |

happiness |

154 |

lovely |

307 |

indeed |

160 |

baby |

267 |

agree |

130 |

protect you |

290 |

crying |

156 |

crying |

250 |

teacher |

128 |

sister |

266 |

anxious |

154 |

pregnant |

246 |

hospital |

128 |

afraid |

245 |

congrats |

149 |

protect you |

240 |

milk powder |

122 |

painless childbirth |

197 |

mom |

142 |

like |

222 |

indeed |

117 |

Figure 2: Top20 keyword word cloud plotted after bullet comment grouping (left is Group 1).

Data analysis shows that the keywords and word frequencies of the two groups differ greatly. In the video bullet comments with a lower-than-average proportion of positive emotion bullet comments in group 1, “not having babies” becomes the first reaction of many women when faced with videos showing the process and experience of childbirth, and they are “afraid” of the “hardship” of having children and are “anxious” about it. However, in the bullet comments of Group 2, it can be seen that many vierers sharing the joy of new mothers in the videos, and congratulations the birth of a new life and the happiness of a new family and expressing their love for the new life.

In Group 1, the bullet comments mentioned “kid” and “mom” in the third-person perspective, and directly stated in the bullet comments that they don’t like children / don’t want to have children or “The third-ranked keyword was “no”, which clearly reflected the audience’s willingness to have children. However, in Group 2, “sister” replaced “mother” as a more intimate form of address and became the second-ranked keyword, which also reflects the change of the audience’s emotional identification with the female Uploaders who have become more intimate.

4.4.LDA Theme Analysis

After completing the sentiment analysis and word frequency analysis of the bullet comments, this study uses Python to conduct a LDA topic analysis to analyse the topics of the bullet comment texts. Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA), a typical bag-of-words model, is an extension of latent semantic analysis and probabilistic semantic analysis, it is one of the most applied machine learning methods in sentiment analysis, which is widely used in text data mining and other fields. After analyzing the consistency and perplexity of sample topics, and by adjusting and viewing the visualization of pyLDAvis several times and comparing the semantic effect, this study chose k=7 as the specified number of topics extracted and obtains the bullet comments’ topic extraction as shown in Table 4.

Table 4: Topic clustering table of bullet comment classification.

| Classification Theme | Sub-Theme | Number | Subject Feature Words | Possibility | Childbirth Choice and Consideration | Birth expectation expression | Subject 1 | Child, Birth, Love, Like, Want, Everything goes well, Hope, Agree, Giving birth | 16.80% | Assessment of the cost of childbirth | Subject 4 | Not to have a baby, God, Wish, Confinement in childbirth, Eat and drink, Milk powder, Body, Dad, Delivery, Breast milk, Pregnancy, Fat and thin, Money | 14.50% | Mother’s role and identity perception | Mother’s role experience | Subject 3 | Mom, Crying, Hardship, Godness, My mother, Male, Envy, Teacher, Husband, Female, Mother, Choice, Birth, Human being, Society | 14.60% | Identity change perception | Subject 7 | Cute, Baby, True, Oh god, Health, Mother-in-law, Family, Woman, Excellent, Kid, Caesarean section, Hard, Hate | 12.20% | Shared Emotion Expression | Blessing emotion expression | Subject 2 | Blessing, Happiness, Heart-breaking, Indeed, Good-looking, Respect | 15.00% | Anxiety emotion empathy | Subject 6 | Fear, Pain, Agree, Awesome, Anxiety, Thanks, Share, Thank you, Breastfeeding, Cause, Condition | 12.40% |

Table 4: (continued).

Female life common value Subject 5 Sister, Really good, Congratulations, Care, Physique, Godness, Life, Pain, Painless, Selfish, Pregnancy, Rich 14.40%

Based on the theme word extraction, three primary classification themes and seven sub-themes were set in this study. The primaryl themes are:

(1) Childbirth Choice and Consideration: including expressions of expectations of childbearing, love for children and visions of a better family, as well as considerations of the material and spiritual costs of childbearing and of family and social relations;

(2) Mother’s role and identity perception: including descriptive expressions of the experience of motherhood and sharing of perceptions of identity change;

(3) Shared Emotion Expression: including the expression of blessings for the birth of Up’s children, the empathy of negative emotions and the exploration of the value of the life of the female community.

5.Research Findings

Based on the content analysis of the sample videos and bullet comments, and with reference to the results of the thematic analysis of the bullet comments, this study conducts a qualitative analysis of the data sample from three perspectives: information dissemination and discourse construction, activation of individualistic identity, and group identity and emotional interaction, to explore the empowering role of the Bilibili platform for women.

5.1.Information Dissemination and Discourse Construction

Compared to traditional media, the openness, interactivity, virtualization and compatibility of the Internet provide women with more opportunities to expand their individual knowledge boundaries and social networks, and thus gain more information about fertility-related and subjective needs. In addition, video sharing platforms such as Bilibili have contributed to the deconstruction of traditional gender culture and the awakening of women’s gender consciousness, reshaping women’s discourse so that women no longer appear to be the traditional Chinese image of devotion to their husbands and children, but rather show a fuller and more comprehensive female character, broadening the space for women’s discourse.

After becoming financially and mentally independent, women can boldly make their decision to “not having children for life” (Video 3) publicly, expressing their opinion that “women’s physical health is more important than having children”; or directly discuss with their husbands that “they will not be responsible for the upbringing and education of the child after the birth, but the father should take more responsibility” (Video 31). More promisingly, some of the birth videos go beyond the individual to bring “postnatal depression” into the public as an officially confirmed and widespread mental illness from the perspective of health communication (Video 15, 37), or to explore topics such as sex during pregnancy (Video 28), breastfeeding after childbirth (Video 20, 36, 39) and women’s postnatal leakage (Video 29), which had been “symbolic annihilation” by the mainstream media.

Liu & Song categorized their respondents’ perceptions of reproductive risk under the influence of social media use into four dimensions: perceived health risk, perceived economic risk, perceived work risk, and perceived environmental risk, and concluded that the more frequently women use social media, the more likely they are to be influenced by online thinking [17]. In the study cases, most of the uploaders directly or indirectly talked about the risks and costs they need to face in order to have children. For example, in her video (Video 21), the uploader Quanxixi summarizes the five major costs of childbirth, namely physical changes and pain, the inability to empathize with her husband and family, differential treatment in the workplace, and society’s harshness toward mothers-to-be and the sense of being emotionally uncontrollable. When faced with this kind of video content, many female viewers will express their fertility tendencies in the bullet comments, such as “not having babies” or “single forever”, in order to make more positive expressions and autonomous decisions on fertility choices.

At the same time, based on the analysis of the bullet comments, this paper argues that Chinese women are facing great contradictions and complex psychology in terms of their reproductive choices. On the one hand, more women in modern society have the opportunity to work and the means to earn their own living, and many women are reluctant to enter into an unsatisfying marriage prematurely due to the cost of childbirth and are unwilling to have children that may affect their career, health and lifestyle. On the other hand, many modern single women have idealistic expectations and hopes for marriage and love, and they are not averse to having children and raising the next generation. This way, young parents will know how to have a lovely child in a scientific and effective way and avoid the risks of childbirth as much as possible (Video 6). This study argues that this contradictory view of fertility is a necessary stage in the transformation of women’s perceptions in today’s society, and that as social structures and fertility policies are adjusted, social attitudes become more open and inclusive, and women have more economic and reproductive autonomy, young women’s views on fertility will move into a more liberal and autonomous stage.

5.2.Activation of Individualistic Identity

Post-feminism came to the forefront in the 1960s and 1970s and encouraged women to develop individualized self-definition and self-expression. Individual choice and motivation, self-empowerment, bodily autonomy, and “women as sexual subjects” are the core elements of post-feminism. New media empowerment at the individual level echoes this by focusing on how individuals can use media tools to bring about an awakening of self-awareness and a breakthrough of their original values in the process of information acquisition and self-challenge. This study argues that by uploading and distributing fertility videos on B, female uploaders have completed a process of examining and speaking about their female bodies and self-awakening to their female identity. Women can engage in richer physical displays and discourses on B-site, which also brings about a more diverse media image of women. In the study video, pregnant women began to show their raw, coarse, untouched bodies generously, which can be seen as an offensive statement against the aesthetic hegemony constructed by the conspiracy of male society and capital. Moreover, it can be seen as a reconstruction of the value of the body among women, who re-perceive their changing bodies and actively choose to show their imperfect bodies, building an authentic discourse of women’s body writing.

Through the analysis of video content and bullet comments, this study also found that concerns about changing interpersonal relationships and anxiety about changing identities became a consideration in women’s reproductive choices. In many of the videos, female uploaders expressed their helplessness and confusion about the loss of control over their bodies and lives during pregnancy. For example, “Shishuyaoya” said, “The incision of a cesarean is like a scar, which often makes me feel like I’ve suddenly lost control of the body I’ve known so well for 30 years. My body suddenly has an extra scar, and I don’t know if this scar will grow or not, or if it will get worse, and this unknown scares me.” (Video 6), and the uploader “Quanxixi” said, “My life floated up during pregnancy...my only goal in life at the time seemed to be to get into the delivery room. My uncontrollable appetite was a way to relieve the loneliness and the uncontrollable feeling of being out of control” (Video 21). Many videos with corresponding bullet comments also mention the problems of getting along with family members and colleagues, such as husbands and mothers-in-law, during pregnancy, as well as express anxiety about post-pregnancy child rearing and the construction of mother-child relationships. In the process of becoming a mother and being given a new identity, women inevitably feel the loss of identity perception, and these expressions precisely reflect the awakening of women’s self-awareness from the side. They begin to focus on the exploration of life essence and self-subjectivity and emphasize the need to examine and control the female body.

5.3.Group Identity and Emotional Interaction

The public video platform medium represented by Bilibili not only promotes the self-empowerment of multiple videos publishing subjects, thus making the construction of self-identity possible, but also attracts specific audiences and drives group empowerment of female communities based on the empowerment of a single individual. This study argues that the childbirth videos on Bilibili provide female viewers with a strong emotional affiliation for value confirmation, forming a dynamic group with an identity, and thus gaining access to online discourse through group empowerment.

In the local digital space, sisterhood has become a feminine force of solidarity and solidarity based on empathy rather than politics [18]. Sensing each other’s needs and suffering, women are closely related, not only generating strong empathy, but also willing to help their sisters in distress, thus seeking a female-specific identity in the digitally connected realm. In the bullet comments of the sample videos, there are indeed “so true” and “real”, and when the Uploader describes the pain of childbirth, instant “feel the pain” bullet comments float by; when Uploads show vulnerability and sadness, viewers send comforting messages such as “hugs” and “heartaches”; when women Uploaders are helpless and angry because their loved ones don’t understand, the audience expresses anger......all of which reflect the warmth of the women of childbearing age in the cyberspace. In the constant exchange of emotions and different perspectives, video Uploads, as opinion leaders on fertility topics, continue to produce similar videos. This further feeds into the discourse production practices of women’s self-media, pushing female content producers to build a broad discourse space in cyberspace, forming a discourse community of women’s mutual support, and creating both “female empowerment” and “sisterhood” two alternative frameworks for gender discourse [19].

It can thus be seen that online content as childbirth videos gather a community of women’s emotions, with viewers achieving psychological healing through empathy and mutual support, and, to a deeper extent, awakening women to reflect on and resist their own situation, ultimately promoting the development of the defence of women’s rights.

6.Conclusion

In the light of empowerment theory, this study analyses women’s childbirth-related videos and their bulletins on the Bilibili platform, and examines the phenomenon and impact of how media empowerments of women from both the content-production side and the audience side. The study finds that, as a public video-sharing platform, Bilibili provides a channel for women of marriage and childbearing age to express themselves. On the one hand, female uploaders use media tools to actively think and express themselves, completing their self-empowerment and self-awakening of their own female identity, piecing together a complex map of contemporary women’s perceptions of marriage and childbearing. On the other hand, female audiences express the power of mutual support in the form of re-posts, likes and comments, thus bringing wide attention to issues such as women’s bodies and emotions, building a solid community of women’s emotions and further expanding the space for women’s public discourse.

Although social media is making progress in women’s empowerment and development, there are still many issues that need to be addressed. Due to the non-neutral nature of social media, everyone’s visibility is not equal, and women’s plight and oppression are still not deeply present and fundamentally dissolved. At the same time, there is a large number of disadvantaged groups in China who do not enjoy the right to media expression due to digital inequality, therefore the empowerment of women in social media, which is the focus of this study, is still the “empowerment of a few”, more empowerment should be given to a wider and disadvantaged group of women. Moreover, media development has made the new landscape of civil opinion more complex, and gender issues are developing in a more complex and difficult to define direction.

To sum up, it is worthwhile to focus, question and explore how to empower women on the Internet further and how to provide the disadvantaged with free and fair access to information and a voice. It is a long way to go before the sword of the media is used to pierce the barren landscape and fight for the rights of you, me, her and others, and ultimately to promote the rights of women in the real world.

References

[1]. Rogers E M, Singhal A. (2003) Empowerment and Communication: Lessons Learned From Organizing for Social Change. Annals of the International Communication Association, Routledge, 27(1), 67-85.

[2]. Ding Wei. (2009) New media and empowerment: A practical social research. International Journalism, 10, 76-81.

[3]. Perkins D D, Zimmerman M A. (1995) Empowerment theory, research, and application. American Journal of Community Psychology, 23(5), 569-579.

[4]. Feng Jianman. (2020) #SeeWomenWorkers: Female Self-Media and Discursive Activism in the Covid-19 Epidemic. Journalist, 10, 32-44.

[5]. Svensson J, Wamala Larsson C. (2016) Situated empowerment: Mobile phones practices among market women in Kampala. Mobile Media & Communication, SAGE Publications, 4(2), 205-220.

[6]. Mao Yanhua. (2021) A Review of Western Maternity Studies in a Postmodern Context. Foreign Languages and Cultures,5(2), 9-18.

[7]. O’Reilly, A. (2004). From motherhood to mothering: The legacy of Adrienne Rich’s Of woman born. State University of New York Press.

[8]. McCabe J, Rich A. (1978) Of Woman Born: Motherhood as Experience and Institution. Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies. 3(2), 77.

[9]. Wang Lei. (2022) Motherhood strategies: maternity practices of urban middle-class women during pregnancy and childbirth. Social Construction, 9(3), 64-78.

[10]. Lin Xiaoshan. (2011) Imagining motherhood: Prenatal checkups, bodily experiences and subjectivity of urban women. Society, 31(5), 133-157.

[11]. Li Yu Bai. (2020) Women’s bodily experiences and embodied practices in fertility events based on a study in Gannan Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture. Society, 40(6), 157-185.

[12]. Li Mengzhu. (2022) Social media empowerment: the construction of maternal autonomy by WeChat parenting groups. Contemporary Youth Studies, 3, 68-74.

[13]. Gao Biye. (2021) Maternity and maternal empowerment practices in Chinese women’s motherhood. Guangdong Social Science, 3, 198-209.

[14]. Han Hong. (2009) Global communication and citizen media monitoring: Cyber activism in contemporary China from the “anti-CNN” website. Journal of Zhengzhou University (Philosophy and Social Science Edition), 42(1), 172-176.

[15]. Shaw F. (2012) The Politics of Blogs: Theories of Discursive Activism Online. Media International Australia, SAGE Publications Ltd, 142(1), 41-49.

[16]. Berelson B. (1952) Content analysis in communication research. New York, NY, US: Free Press, 220.

[17]. Liu Juan, Song Tingting. (2022) “Rendered anxiety”: social media use and women’s perception of fertility risk. Media Watch, 6, 79-86.

[18]. Cao Jin, Dai Shiju. (2022) “Empowerment or Negative Power: A Study of New Communication Technologies and the Construction of Gender Power Relations. Journalism and Writing, 11, 5-17.

[19]. Zeng LH, Ye DY, Li P. (2021) The “visibility” of women’s “activism” in the context of social media empowerment: an examination of the “availability” of the B station beauty video community. Journalist, 9, 86-96.

Cite this article

Hua,S.;Jiang,Y. (2023). Research on Social Media’s Empowerment of Women’s Childbirth Rights -Taking Bilibili Platform’s Female Childbirth Videos as an Example. Communications in Humanities Research,7,323-335.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Educational Innovation and Philosophical Inquiries

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Rogers E M, Singhal A. (2003) Empowerment and Communication: Lessons Learned From Organizing for Social Change. Annals of the International Communication Association, Routledge, 27(1), 67-85.

[2]. Ding Wei. (2009) New media and empowerment: A practical social research. International Journalism, 10, 76-81.

[3]. Perkins D D, Zimmerman M A. (1995) Empowerment theory, research, and application. American Journal of Community Psychology, 23(5), 569-579.

[4]. Feng Jianman. (2020) #SeeWomenWorkers: Female Self-Media and Discursive Activism in the Covid-19 Epidemic. Journalist, 10, 32-44.

[5]. Svensson J, Wamala Larsson C. (2016) Situated empowerment: Mobile phones practices among market women in Kampala. Mobile Media & Communication, SAGE Publications, 4(2), 205-220.

[6]. Mao Yanhua. (2021) A Review of Western Maternity Studies in a Postmodern Context. Foreign Languages and Cultures,5(2), 9-18.

[7]. O’Reilly, A. (2004). From motherhood to mothering: The legacy of Adrienne Rich’s Of woman born. State University of New York Press.

[8]. McCabe J, Rich A. (1978) Of Woman Born: Motherhood as Experience and Institution. Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies. 3(2), 77.

[9]. Wang Lei. (2022) Motherhood strategies: maternity practices of urban middle-class women during pregnancy and childbirth. Social Construction, 9(3), 64-78.

[10]. Lin Xiaoshan. (2011) Imagining motherhood: Prenatal checkups, bodily experiences and subjectivity of urban women. Society, 31(5), 133-157.

[11]. Li Yu Bai. (2020) Women’s bodily experiences and embodied practices in fertility events based on a study in Gannan Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture. Society, 40(6), 157-185.

[12]. Li Mengzhu. (2022) Social media empowerment: the construction of maternal autonomy by WeChat parenting groups. Contemporary Youth Studies, 3, 68-74.

[13]. Gao Biye. (2021) Maternity and maternal empowerment practices in Chinese women’s motherhood. Guangdong Social Science, 3, 198-209.

[14]. Han Hong. (2009) Global communication and citizen media monitoring: Cyber activism in contemporary China from the “anti-CNN” website. Journal of Zhengzhou University (Philosophy and Social Science Edition), 42(1), 172-176.

[15]. Shaw F. (2012) The Politics of Blogs: Theories of Discursive Activism Online. Media International Australia, SAGE Publications Ltd, 142(1), 41-49.

[16]. Berelson B. (1952) Content analysis in communication research. New York, NY, US: Free Press, 220.

[17]. Liu Juan, Song Tingting. (2022) “Rendered anxiety”: social media use and women’s perception of fertility risk. Media Watch, 6, 79-86.

[18]. Cao Jin, Dai Shiju. (2022) “Empowerment or Negative Power: A Study of New Communication Technologies and the Construction of Gender Power Relations. Journalism and Writing, 11, 5-17.

[19]. Zeng LH, Ye DY, Li P. (2021) The “visibility” of women’s “activism” in the context of social media empowerment: an examination of the “availability” of the B station beauty video community. Journalist, 9, 86-96.