1.Introduction

Edward Hopper is a representative of the school of American realism painting. The movement of American realism first started from literary works in the mid-19th century, and it is an artistic style that focuses on the authentic everyday life of ordinary people in the American society. Works of American realism generally include comments and discussions on the impacts of war, politics, or daily struggles faced by people in their life.

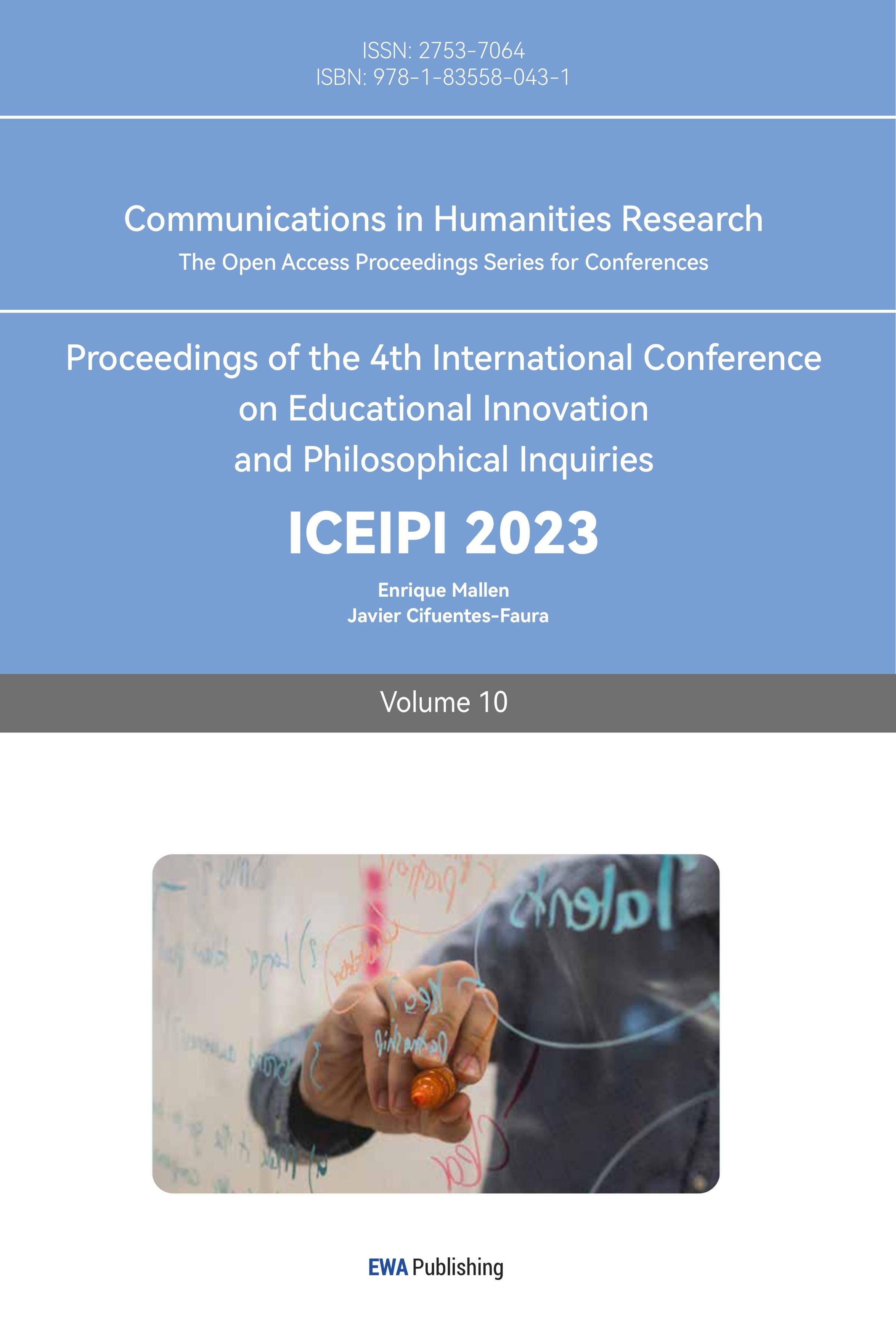

In careful analysis of Hopper’s works throughout his career, one finds that there are certain objects and depictions that appear and reappear frequently, such as empty streets, isolated houses, and lonely figures. These renderings contribute to a deep sense of alienation, which has been a common and salient theme in Hopper’s art. The one or very few people featured in his paintings seem to always be isolated and engulfed by loneliness. For instance, in the famous Nighthawks (Figure 1), Hopper creates a peaceful, yet enigmatic street scene at night. The painting did not refer to any specific real-life setting, but an imagined world, left to the viewer’s own interpretations. The figures are all disconnected from one another and indulge in their own world of thought. The viewers are prompted to wonder about the relationship among the subjects, the emotions they feel, and the business in which they are engaged. Hopper himself recalled, saying, “unconsciously, probably, I was painting the loneliness of a large city” [1].

Figure 1: Nighthawks, 1942. Oil on canvas, 84.1 by 152.4 cm. The Art Institute of Chicago [2].

Generally speaking, the figures, the setting, and the ambiance of Hopper’s paintings were relatable to most Americans during his time, as they embody the mentality and the emotions of an average American back then. The Great Depression led to large-scale unemployment and poverty, and the following World War II caused great loss and instability in the society. Uncertainty for the future widely evoked anxiety and worries among the public. Alienation is not only a salient theme in Edward Hopper’s paintings, but it also represents an atmosphere that permeated the entire society. The question of where the phenomenon of alienation originates from has long intrigued scholars, and this paper attempts to examine Edward Hopper and his works as a lens to analyze the potential external and internal causes of alienation, and the techniques Hopper employed to render such a feeling in his paintings.

2.History of Research on Alienation

The history of alienation as a concept is older than the term itself. The idea of alienation can be traced back to the Old Testament, when discussing how “the idol represents [the idolatrous man’s] own life forces in an alienated form” [3]. The history of research on the phenomenon of alienation has been long as well, and yet it still appears so multidimensional and sophisticated that analysis on any particular aspect would be insufficient to define its causes and reveal the way to avoid its undesirable effects [4]. It is widely recognized that alienation needs to be studied in the social and historical context it emerges in. Alienation also needs to be examined as a relational and interactional concept between an individual and the social structural conditions [5]. According to Professor Matao Noda from Kyoto University, the study of alienation today needs to be based on the characteristics of modern civilization, including the rapid urbanization, industrialization, and development of technology. These are described as a form of new evil that man is exposed to after being released from the old forms of “slavery and decadence.” [4]. Therefore, the phenomenon of alienation is quite pervasive in modern society. Before we begin to delve deeper into the causes and nuances of alienation, we first need to understand its definition.

3.Definition of Alienation

A very basic definition of alienation is when a person’s or a group’s experience is materially in conflict with everything else in the society. It appears when there is a gap between one’s individual view and what’s given in the world, or between one’s inner and outer spaces. Alienation can be experienced as feelings of anxiety, mental suffering, or desire for inner harmony by some “oversensitive individuals” [4]. This aspect of alienation is reflected in a relatively old definition for alienation: when the English word “alienation” is first adopted from the French “aliené” in 1482, it was defined as “loss of derangement of mental faculties; insanity” [3]. A more modern definition from the Oxford dictionary would be “the action of estranging, or state of estrangement in feeling or affection” [6]. What hasn’t changed about the definition of alienation is that it is generally associated with negative effects or feelings.

Sinari mentions that an alien moves between a state of “forlornness” and a “rational or imperative I-should-belong-somewhere-state.” Seeman proposes that there are mainly five manifestations of alienation, namely, alienation in the sense of powerlessness, meaninglessness, normlessness, isolation, and self-estrangement [7]. It is common for aliens to express their experience through forms of art or symbolism, such as poetry and paintings [4]. Furthermore, art is a commonly known means through which to counter the alienated society we perceive. Jarrett argues that art is a way for people, who are aware of “divisiveness, of exploitation, of discrimination, of unfairness, of exclusiveness, of puritanical inhibition, of the locked-in, of snobbishness, of stuffiness, of hierarchies,” to counter these forces that alienation consists of [8]. This, again, reinforces alienation’s negative and undesirable attribute. Yet in this case of countering alienation through art, the response is creative and aesthetical. Therefore, it might be fairer to conclude the nature of alienation as dual and complex, rather than solely negative.

4.External or Societal Causes of Alienation

What exactly causes a person to experience alienation? We can trace the causes to both external and internal factors. The external factors refer to the societal causes. One of the most examined frameworks of understanding alienation is developed by Marx, based on workers and their work. Marx indicates that a “capitalist division of labor and the critical link between human existence and the social relations of production in a capitalist society” is what leads to fragmentations in human existence. Since the life experiences of humans are related to the material and social conditions, the capitalist division of labor results in the “separation of individuals from the natural activity of labor.” Eventually, there is also going to be a sense of confrontation between the worker and the product produced. As alienation has an increasingly impactful effect on the worker, he will be separated from things that surround him [5].

In examining the causes of alienation, Blauner [9] also pointed to the impact of industrialization and advances in technology. In the late 19th and early 20th century, industrialization and urbanization expanded rapidly in the United States. Skyscrapers began to dominate the skyline and people were living in more concentrated regions. Productivity largely increased, accelerating economic growth. Many of Hopper’s works, like many other works of American realism, focus on this kind of Modern life. Yet Hopper didn’t like the change. He felt lonely, and sensed loneliness and agony in many other individuals as well [6].

5.Personal Experience Contributing to Alienation

Not only was Edward Hopper influenced by the social-historical environment of his time, but his personal experience also contributed to his sense of isolation. He was born on July 22, 1882, to a middle-class, highly respected family in Nyack, New York. His father, Garret Henry Hopper, was a merchant in the dry goods business. He owned a big library and his love for reading has influenced his son. Hopper’s father was usually absent from home, so Hopper grew up in a female-dominant house. The money of the family came from Hopper’s mother, Elizabeth Griffiths Smith, and maternal grandmother. Other than his mother and grandmother, Hopper also lived with his older sister and the house maid. It is likely that growing up as almost always the only male in the house and the lack of masculine energy around him evoked a deep sense of difference inside Hopper and made him very self-conscious.

One of Hopper’s earliest experiences of alienation also comes from his height—he has grown to be six feet five inches at the age of twelve, which was quite tall and made him stand out like an anomaly among his peers. His schoolmates, making fun of him, called him “Grasshopper” [10]. This has discouraged Hopper from spending time with his peers, and he ended up spending most of his time reading and painting alone. [6].

Hopper has shown exceptional talent for painting since a young age. As a teenager, he drew many self-portraits representing himself in a realistic way. Hopper was unsatisfied with his height and body features, yet in art he has found a creative outlet and a world to which he could escape. So, he freely expressed his obsessions with art [6]. Hopper may have experienced alienation from himself, as there was an ongoing conflict between his tendency to express things in a realistic way and his unsatisfaction with realistic things, namely, his height and body features.

Moreover, when Hopper was determined to pursue a career in art, although his parents were supportive of his decision, they hoped that he would study commercial art to guarantee a future with good income [6] Even though Hopper’s artistic skills in the fields of oil painting, etching, watercolors, and many other media of art were impressive, he still couldn’t make enough money to support his own living. Therefore, he became a commercial artist for companies in New York [6]. Hopper has always been against the idea of pursuing a career in commercial art, yet he had no other choice than to surrender to reality. This inner conflict may have contributed to his feelings of being alienated from a society where a state of material abundance is crucial for living.

Hopper married Josephine Nivision in 1924. Josephine was his classmate from art school. She was an artist and earned her living through teaching elementary school students art. Hopper and Nivision stayed together for the rest of their life. They shared their love for cinema, literature, and French culture, although they were entirely different people. Josephine was “outgoing, communicative, chatty, and liberal.” In contrast, Hopper was “introspective, shy, quiet, cryptic, and conservative” [6]. Josephine put in much effort promoting her husband’s work, which brought Hopper wide public recognition. She also contributed to Hopper’s art creation, “posing for his female subjects, exchanging ideas, and reacting intelligently to (and keeping records of) his painful progress” [11]. Josephine gave up her own career to become Hopper’s wife, assisting him to become a renowned artist.

According to Josephine’s diaries, Hopper was not supportive of her art career. He preferred that she become his housewife. From Josephine’s perspective, Hopper was somehow abusive. However, there is also evidence that Hopper also experienced emotional suppression from Josephine [11]. In the pencil cartoons he drew between 1933 and 1952, he portrayed himself as a victim of Josephine’s aggressive character. He named one of the cartoons “He cannot choose but hear” (Figure 2), depicting Josephine’s dominant position in their arguments. They both have similar experiences of feeling suppressed in this relationship, aggravating the sense of alienation between the couple. Hopper’s relationship with his wife may have affected the way he depicted couple relationships in his later paintings.

Figure 2: “He cannot choose but listen”, 1933-1952 [12].

6.Exploration of Hopper’s Techniques of Representing Alienation Through Selected Works

Out of all the manifestations of alienation, isolation is most applicable for alienation represented in art. Alienation in the sense of isolation refers to those who “assign low reward value to goals or beliefs that are typically highly valued in the given society.” People experiencing this type of alienation are generally intellectually detached from popular cultural standards [7]. The fact that one doesn’t believe he belongs to a society prompts the idea of wanting to build a new society, where they belong—usually of arts, religion, or symbolism [4].

Focusing on Hopper's paintings, I have selected 5 works that illustrate his sense of alienation in various ways and will analyze his methods respectively of representing such a feeling.

Figure 3: Soir Bleu, 1914. Oil on canvas. 91.4 by 182.9 cm. Whitney Museum of American Art [13].

Soir Bleu (Figure 3) was painted in 1914, before Hopper becomes commercially successful. “Soir bleu” means “blue evening” in French. It depicts a melancholic scene in a French café under a blue evening sky. Even though there is a total of seven people in this scene, loneliness permeates the crowd. On the very right of the painting, there is a bourgeois couple sitting opposite of each other. On the left of the painting, there is a man smoking a cigarette. According to one of Hopper’s sketches, this man is referred to as a pimp. This suggests that the woman standing behind is likely a prostitute. Moving towards the center, there are two men with their backs facing the viewer. One of them is a military worker, as we can tell from the epaulets on his uniform. The other man is a bohemian artist. They share a table with the main character—a clown dressed in a striking white costume. Despite the presence of such interesting characters, the clown’s downcast eyes stare emptily at the table while smoking, just like many others in the crowd do.

Instead of presenting loneliness by literally showing a single person, Hopper chose to emphasize the disconnection among different individuals in the same crowd. Everyone in this painting has a different occupation, and likely a different purpose. They seem to be equally lost and melancholic.

If that is the case, then is the clown really the main character? Or is there really any main character? The truth is that we don’t know. Everyone in the painting stares into completely different directions, yet none of them stares at the viewer. There is also no physical interaction among any of the characters. The lack of information acts as a barrier between the viewer and the world within the painting, further emphasizing the idea that everyone is alienated from one other.

Even though we don’t know the exact story behind, the clown can be interpreted as a representation of Hopper himself. The clown seems to be lost, just like Hopper himself at the time this painting was done. At that time, Hopper just came back to America from his trip to Paris. There, he studied a variety of art styles and practiced them. Hopper was still both finding his position as an artist and his own audience. An artist without an audience might feel similar to a clown that fail to make people laugh—lost and purposeless. Hopper is expressing his feelings of alienation that come from a lack of audience and appreciation for his art through the clown in Soir Bleu.

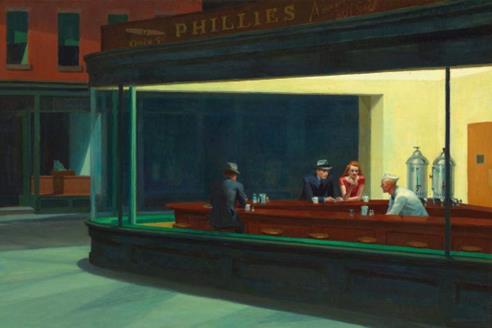

Figure 4: Room in New York, 1932. Oil on canvas. 73.7 by 93 cm. Sheldon Museum of Art [14].

Couples is another common theme in Hopper’s paintings. There seems to always be a sense of estrangement between Hopper’s couples. Room in New York (Figure 4) was painted in 1932. In it, a couple sits inside an apartment during nighttime. They are sitting inside the same warmly lit room, physically close to each other. The walls of the room are painted yellow. The man sits in a red armchair, whose color responds to the red dress the woman is wearing. The colors of their room are warm colors of red, yellow, and brown. In contrast, the viewer is left in the dark exterior that is almost entirely black. We are looking into a window, watching the life of these two strangers whom we do not know, or cannot even see their faces clearly. This was intentionally done by Hopper to make us feel distanced as an outsider.

Yet the distanced does not only consist of the viewer, the couples inside are also distanced from each other. The man and the woman make no interactions with each other. The man quietly reads his newspaper. The woman, turning her back to the man, almost intentionally, is playing a few notes on the piano. She does not seem to be focusing on the piano, since she does not even have both of her hands on it. Her playing is more likely to be pressing a few keys out of boredom. Hopper contrasts the warm environment with the indifferent relationship of this couple, expressing his view on the plain and lifeless relationship between couples who are legally bound but emotionally without much in common.

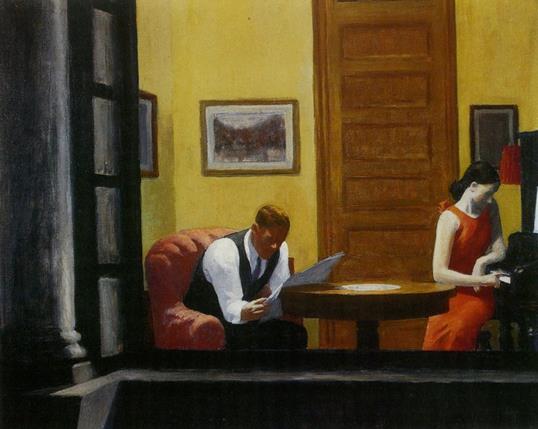

Another prominent example of Hopper’s paintings depicting alienated couples is Summer Nights (Figure 5), painted in 1947. In this painting, a couple stands next to each other outside of a house during a summer night. Again, the viewer is separated from the couple; we stand in the darkness, while they are illuminated by the light from the porch.

Different from Room in New York, there is an extra tension present in this painting. The couple seems to be in a conversation, but neither of them is speaking. There is physical intimacy, but no emotional connection. The man is looking down, and the woman also stares into nothing. We don’t know what has happened between them, but the woman’s expressions are serious and tight. We can clearly sense the disconnection between the couple.

The way Hopper portrays couples could be related to his relationship with his wife. Hopper and Josephine and completely different personalities. Even though they spent their whole life together, there were usually tension and disagreements between them. This may have contributed to his opinion on how many couples, despite staying physically together, do not really share strong emotional connections.

Figure 5: Summer Nights, 1947. Oil on canvas. Private collection [15].

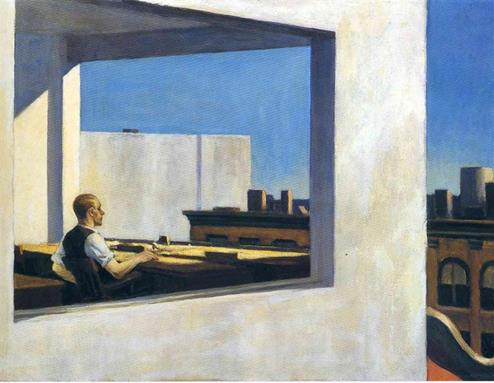

Figure 6: Office in a Small City, 1953. Oil on canvas. 71.1 by 101.6. Metropolitan Museum of Art [16].

Besides crowds and couples, alienation can also be expressed with a single person, such as in Office in a Small City (Figure 6), painted in 1953. This painting shows a continuity in Hopper’s habit of separating his subjects from the viewer with a physical barrier, in this case, the wall of the building. This white building stands in the street of a small city, with blue skies and sunshine. Even though we no longer observe the subject from the darkness, we are again observing him through a window. Furthermore, Hopper used large, square and angular windows to frame the man. Now, the man is not only isolated from the viewer, but more importantly, he is isolated and limited from the rest of the world outside the building.

In this painting, the man is sitting on his working desk in his office. He stares outside the window, not doing any work. The viewer can only see a profile of the man’s face. There is no clear indicator of who he is or what he does. Hopper might be saying that this person could be anyone. This man may not represent any specific person, but it refers to the working public that Hopper observed. Through these depictions of lonely and unidentified people, Hopper reveals the feelings of isolation and loss among the average American working people. As Twining [5] argues, the effect of alienation is especially remarkable on workers because individuals would generally feel separated from the work they do under a society with a capitalist labor division.

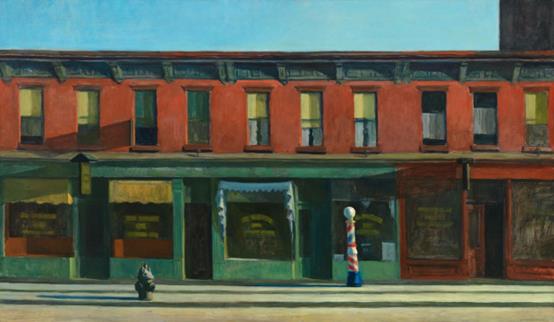

Figure 7: Early Sunday Morning, 1930. Oil on canvas. 89.4 by 153 cm. Whitney Museum of American Art [17].

Finally, alienation is not only present in Hopper’s paintings that include people, but it also exists in scenes that are free from human beings. Hopper’s 1930 painting named Early Sunday Morning (Figure 7) offers a good example. This painting shows a street scene in New York during an early Sunday morning. The streets are empty, deprived of people and no stores are open. The buildings are reduced to the minimum, with a sense of starkness everywhere. The text written on the outside of stores are blurred, only to be expressed by blocks of yellow. It would be difficult for a viewer, unaware of the context, to identify this place.

In this case, there are no longer people in the painting that are alienated from one other. Now, it is us, the viewers, who would generate a sense of loneliness when viewing this painting. We are left all by ourselves, in an unfamiliar place, with no clue of what to do next. This may be how Hopper perceived the world, or at least, how he believed most people would perceive the world.

Furthermore, the fact that this is a familiar place for the painter but not for us creates a gap between the understanding of the painter and our understanding of the world. Hopper might be expressing his thoughts on an existing sense of alienation between artists and their viewers.

7.Conclusion

This paper aims to research into the causes and manifestations of alienation, and admittedly, the reasons and results we identified are not definitive. In addition, every person has his or her own unique experiences that contribute to individually different feelings of alienation, therefore, it is almost impossible to give a comprehensive list of causes. However, the ones we identified do offer a general direction in what could have potentially led to the alienation experienced by Hopper and other individuals in the society he observed.

Throughout his artistic career, Hopper has established his own style—saturated colors, unclear faces, minimalist forms, and day to day scenes, in rendering a sense of loneliness and isolation. By analyzing a selected range of Hopper’s paintings, we explored how Hopper conveys a sense of alienation through his artistic choices and techniques, which cover a great variety, including indifferent crowds, disconnected couples, working people, and man-deprived streets, etc. Hopper’s wide range of subject matters proves the omnipresence of alienation, and the various ways in which he presents these subject matters mirror the extremely diverse manifestations of alienation.

Apparently, alienation is a problem that most individuals in a society encounter. But can alienation be solely regarded as a problem? We cannot be certain about that. As Sinari [4] argues, the core culture of humanity is usually created by the “healthy or creative aliens” of a society, who alienated themselves because of their “supernatural insight, extraordinary genius, spiritual flashes, or reformative zeal” [4].

History has been shaped by people who think differently and in fresh perspectives, who may be regarded as the aliens in their society. Yet it is also clear that the average person does not enjoy being ill-adapted to the world around. This reinforces the duality and complexity of alienation, prompting an even deeper examination of the nature of this concept.

References

[1]. Kuh, Katherine. The Artist’s Voice; Talks with Seventeen Artists. Harper and Row, 1962.

[2]. Hopper, Edward. Nighthawks. 1942. The Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago.

[3]. Overend, Tronn. “Alienation: A Conceptual Analysis.” Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, vol. 35, no. 3, 1975, pp. 301-322. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/2106338.

[4]. Sinari, Ramakant. “The Problem of Human Alienation.” Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, vol. 31, no. 1, 1970, pp. 123-130. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/2105986.

[5]. Twining, James E. “Alienation as a Social Process.” The Sociological Quarterly, vol. 21, no. 3, 1980, pp. 417-428. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/4106303.

[6]. Dalirian, Zohreh. “Alienation in Edward Hopper’s and Jackson Pollock’s Paintings: A Comparison and Contrast.” 2010. Wichita State University, Master Thesis. http://hdl.handle.net/10057/3301.

[7]. Seeman, Melvin. “On The Meaning of Alienation.” American Sociological Review, vol. 24, no. 6, 1959, pp. 783-791. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/2088565.

[8]. Jarrett, James L. “Countering Alienation.” Journal of Aesthetic Education, vol. 6, no. 1/2, 1972, pp. 179-191. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/3331419.

[9]. Blauner, Robert. Alienation and Freedom: The Factory Worker and His Industry. University of Chicago Press, 1964.

[10]. Goldman Rubin, Susan. Edward Hopper: Painter of Light and Shadow. Harry N. Abrams, 2007.

[11]. Butscher, Edward. Review of Edward Hopper: An Intimate Biography, written by Gail Levin. The Georgia Review, vol. 51, no. 1, 1997, pp. 171–74. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/41401015.

[12]. Hopper, Edward. He cannot choose but listen. 1933-1952. https://www.artnews.com/art-news/news/scenes-from-edward-hoppers-marriage-2390/

[13]. Hopper, Edward. Soir Bleu. 1914. Whitney Museum of American Art, New York City.

[14]. Hopper, Edward. Room in New York. 1932. Sheldon Museum of Art, Lincoln.

[15]. Hopper, Edward. Summer Nights. 1947. Private collection.

[16]. Hopper, Edward. Office in a Small City. 1953. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City.

[17]. Hopper, Edward. Early Sunday Morning. 1930. Whitney Museum of American Art, New York City.

Cite this article

Fang,R. (2023). An Analysis of the Causes of Alienation in Edward Hopper’s Works. Communications in Humanities Research,10,269-278.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Educational Innovation and Philosophical Inquiries

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Kuh, Katherine. The Artist’s Voice; Talks with Seventeen Artists. Harper and Row, 1962.

[2]. Hopper, Edward. Nighthawks. 1942. The Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago.

[3]. Overend, Tronn. “Alienation: A Conceptual Analysis.” Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, vol. 35, no. 3, 1975, pp. 301-322. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/2106338.

[4]. Sinari, Ramakant. “The Problem of Human Alienation.” Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, vol. 31, no. 1, 1970, pp. 123-130. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/2105986.

[5]. Twining, James E. “Alienation as a Social Process.” The Sociological Quarterly, vol. 21, no. 3, 1980, pp. 417-428. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/4106303.

[6]. Dalirian, Zohreh. “Alienation in Edward Hopper’s and Jackson Pollock’s Paintings: A Comparison and Contrast.” 2010. Wichita State University, Master Thesis. http://hdl.handle.net/10057/3301.

[7]. Seeman, Melvin. “On The Meaning of Alienation.” American Sociological Review, vol. 24, no. 6, 1959, pp. 783-791. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/2088565.

[8]. Jarrett, James L. “Countering Alienation.” Journal of Aesthetic Education, vol. 6, no. 1/2, 1972, pp. 179-191. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/3331419.

[9]. Blauner, Robert. Alienation and Freedom: The Factory Worker and His Industry. University of Chicago Press, 1964.

[10]. Goldman Rubin, Susan. Edward Hopper: Painter of Light and Shadow. Harry N. Abrams, 2007.

[11]. Butscher, Edward. Review of Edward Hopper: An Intimate Biography, written by Gail Levin. The Georgia Review, vol. 51, no. 1, 1997, pp. 171–74. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/41401015.

[12]. Hopper, Edward. He cannot choose but listen. 1933-1952. https://www.artnews.com/art-news/news/scenes-from-edward-hoppers-marriage-2390/

[13]. Hopper, Edward. Soir Bleu. 1914. Whitney Museum of American Art, New York City.

[14]. Hopper, Edward. Room in New York. 1932. Sheldon Museum of Art, Lincoln.

[15]. Hopper, Edward. Summer Nights. 1947. Private collection.

[16]. Hopper, Edward. Office in a Small City. 1953. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City.

[17]. Hopper, Edward. Early Sunday Morning. 1930. Whitney Museum of American Art, New York City.