1.Introduction

Numerous studies have established a strong relationship between fashion and culture. Culture and fashion have a nuanced and close bond, as they interact and support each other to grow organically and positively. Fashion serves as a reflection of cultural values and ambiance in society. As a particular garment style becomes fashionable, people emulate it and disseminate the underlying cultural concepts it represents. Brands play a crucial role in connecting fashion, culture, and consumers. This study discusses the relationship between fashion and culture through the historical background of Yves Saint Laurent’s Le Smoking suit, highlighting the influential role of luxury brands and their mediating function in shaping consumer identity and personality.

2.Cultural Influence in Fashion

Fashion represents externalization while culture signifies connotation. Holt [1] indicates that Fashion brand is essentially a product rooted in culture that serves as a means of expression and manifestation. The reason why fashion proves to be a successful carrier of culture is because the two share common characteristics. Fashion, like culture, is a popular phenomenon that spreads widely within a particular period, region, or group. The time-dependent feature of fashion is destined to form, become popular, and disappear within a certain period of time. In contrast to traditional culture with its long history and historical sedimentation, fashion is more attuned to the spirit of the times and is a prominent reflection of various developmental stages. Additionally, Berthon et al. [2] states that fashion has collective characteristics and people from different classes, genders, and backgrounds typically form different social groups due to their unique cultural values and orientations. Yves Saint Laurent greatly exemplifies how brands create items that are inspired by cultural changes.

The style of garment design during a particular time period is heavily influenced by the culture of that era. Designers draw inspiration from their specific environment, creating works that are in tune with the zeitgeist. According to Jiang [3], during the Renaissance, which thrived from the 16th through the 17th centuries, burgeoning middle-class affluence and advances in knowledge and culture gave rise to the Baroque art style, which, in turn, informed fashion. This led to the widespread use of opulent materials such as silk and ornate embellishments like embroidery and jewellery.

3.Historical Background of Women’s Suit

In the eyes of sociologists, Sproles discusses [4] fashion is largely shaped by the privileged elite in society, with these trends trickling down from the upper echelons. However, the fashion industry has seen two successful bottom-up trends emerge: the ‘Hippie Culture’ and ‘Street Culture.’ Following the post-World War II economic crisis in the early 20th century, the Hippie movement became the first large-scale impact on American mainstream culture. Although it ultimately failed, the spirit of rebellion, innovation, simplicity, and environmental protection embodied in this movement has subtly influenced the developmental trajectory of human society and breathed new life into mainstream culture. Consequently, as Cosma states [5] a free-spirited upbringing nurtured a cohort of young people with self-focused attitudes, known as the “Beat Generation”. The fashion trends of this era were aligned with the societal shift towards embracing individualism, with the “Beat Generation” daring to wear and pursue whatever they loved, regardless of societal conventions. This open environment encouraged innovation in garments, with the introduction of the miniskirt, Le Smoking suit, and Unisex style garments, all of which were influenced by feminism.

Prior to 1910, there was no authentic women’s suit. However, some daring designs laid the foundation for the transformation of the suit. With the rise of feminist consciousness in Western countries during the 1920s, women actively pursued the right to enter the workplace, gained discourse power in the economy and politics, and suits became a staple in many women’s wardrobes. Coco Chanel, a proponent of feminism, forsook the outdated notion that women should only wear skirts and drew inspiration from men’s clothing. With the design of the Tweed Suit, she relaxed the constraints at the waist, heightened the strong sense of lines, and created the prototype for the first women’s suit, marking a significant change in clothing history. Today, her style remains a classic in the fashion industry, as the Chanel Tweed Suit established the first female suit and is considered the predecessor of the power suit [6].

In the 1960s, fueled by increasing social freedoms, the feminist movement gained momentum. To truly understand fashion history, we must view it as a linear storyline. It is not solely an evolution of clothing, but rather a depiction of women’s independence and liberation. The introduction of the power-suit represents a significant turning point in women’s fashion, showcasing their capability to be assertive and pragmatic, while also embracing their charming and graceful qualities. Nevertheless, what exactly defines a power-suit? Is it exclusively associated with feminism? Who has the privilege of wearing it?

4.The Approach of Le Smoking Suit

If Coco Chanel liberated women’s fashion, Yves Saint Laurent empowered them. In 1930, German actress Marlene Dietrich played a dancer in the film “Morocco”. She wore a silk top hat and a men’s tuxedo on the stage (Figure 1), the appearance that a woman disguised as a man has shocked the audiences. More boldly, Marlene even stepped down and kissed a woman.

Figure 1: Morocco 1930.

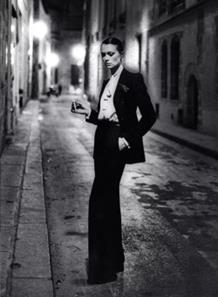

The film won four Oscar nominations at that time. This gender-bending attire caused quite a commotion among audiences. Following this iconic outfit, Yves Saint Laurent introduced Le Smoking- the first women’s suit in 1966. It received an enormous response and quickly became a fashion sensation. As figure 2 shows, Le Smoking refers to the black casual shirt worn by affluent men in smoking rooms to prevent the odor of cigars from sticking to their clothes. Yves Saint Laurent reinvented it and created a revolutionary style that women could wear.

Figure 2: Helmut Newton, 1975, Vogue.

Yves Saint Laurent’s unconventional approach was met with criticism from both the industry and society at that time. Yves Saint Laurent is a significant fashion brand that challenges the traditional notions of gendered clothing and promotes a more gender-neutral style. The brand’s designs embrace hermaphroditism, blurring the lines between traditional men’s and women’s fashion and becoming a timeless classic. The amalgamation of men’s and women’s clothing characteristics shattered numerous restrictions imposed on women’s clothing in France during that time [7]. Additionally, Yves Saint Laurent was being the first designer to feature a black model on the runway, challenging the social discrimination of the time.

Whenever a new culture emerges, its trends are absorbed and propagated by the corresponding groups. Of all these groups, McNeill’s research [8] found out that women are the most heavily influenced by fashion culture and they are also the backbone driving the evolution of fashion. At that time, women who dared to don YSL’s suits were powerful and self-assured, including the likes of Bianca Jagger, Liza Minnelli, and Nan Kempner - all influential female leaders in various industries who advocated for women’s independence and liberation [9]. Their vocal support and publicity helped solidify Yves Saint Laurent’s unconventional suits as an alternative option in the fashion industry.

Le Smoking Suit brought a significant shift in the restrictive gender norms of the fashion industry. The current openness and flexibility regarding gender in fashion are the result of the persistent struggles and innovative efforts of earlier generations. Since then, Le Smoking Suit has been studied by designers and creative directors worldwide, from Tom Ford’s power suits to Hedi Slimane’s sharply cut designs. The silhouette has been re-imagined through a variety of lenses [9]. The evolution of women’s suits has gradually permeated from upper elite’s haute couture to middle class accessible commercial labels such as Massimo Dutti, Mango, H&M, Zara. The fashion industry supported the women’s rights movement, using clothing styles to help women adapt to new roles and express social demands.

The enduring influence of Le Smoking Suit on the brand is still felt today, as the style adapts to changing trends and fashion eras. The Saint Laurent 22AW Woman Collection (Figure 3) draws inspiration from the brand’s archives and recreates the bold and seductive looks of the 1970s, showcasing the strength and soft power of women who wear Yves Saint Laurent. The brand has always been at the forefront of advocating for women’s rights and promoting the beauty of women in all their diversity.

5.Brand and the Curated Self

Le Smoking Suit played a significant role in influencing consumers’ self-concepts and defining their self-identity by acting as a carrier and transfer of meaning. As Figure 4 Kapferer’s model [10] provides a perspective on how brands shape identity by introducing the concept of self-image, which enables consumers to co-construct images with other consumers, brand communities, and other reciprocal parties. Brands perform an intermediate function in shaping communities and guiding consumers towards discovering a sense of affiliation with a group of like-minded individuals who share similar values, social standing, and tastes.

The significance of women wearing suits in society is to challenge gender biases, strive for parity and exhibit individual autonomy and influence. This sartorial choice grants women greater autonomy and influence, while also fostering a more inclusive and varied perspective throughout society. As emphasized by Keller [11], symbolic worth such as Le Smoking Suit is crucial for brand that is socially prominent, serving as instruments for social cohesion and affiliation. It functions as an abstract language by consumers in the pursuit of social communication.

From a dominant individualist perspective, suits are commonly viewed as formal and commanding attire, wearing a suit gives a sense of confidence and potency. For females, this sensation can bolster their self-assurance and assertiveness in professional and social scenarios. Belk argues [12] brands possess symbolic value, and their products can fulfill emotional needs, allowing individuals to differentiate themselves and express individuality. If consumption of a specific brand aligns with an individual’s characteristics or creates a strong emotional connection, then consumers are inclined to develop a robust attachment to the brand. Escalas and Bettman [13] suggest that consumers transfer meaning from a brand to themselves by “selecting brands that are relevant to a specific aspect of their current self-concept or possible self”. Interestingly, Berger and Heath states [14] the consumption of brands serves as cues towards one’s identity. It shows who we are and who we want to become, consumers often see the brand they use as a representation of their self-expression, creating a curated self alongside the brands [15].

6.Conclusion

Fashion is more than just about the exterior. It embodies an attitude, a harmonious combination of colors, tailoring, and style, and these reflect one’s inner tastes and cultivation. Thus, fashion is more about the soul within it, rather than just the outer shell. Furthermore, the correlation between social culture and fashion is cyclical in nature. And fashion consumption is a behavior that varies by culture and fashion blossoms only when culture thrives.

References

[1]. Holt, D. B. (2004). How brands become icons: The principles of cultural branding. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

[2]. Berthon, P., Pitt, L., Parent, M., & Jean-Paul Berthon. (2009). Aesthetics And Ephemerality: Observing And Preserving The Luxry Brand. California Management Review, 52(1), 45–66. doi:10.1525/cmr.2009.52.1.45.

[3]. Jang, S. E. . (2007). A study on the clothing styles of renaissance and baroque focused on H.Wolfflin`s Methodology. The Journal of the Korean Society of Costumes, 57(7), 15-29.

[4]. Sproles, G. B. (1981). Analyzing Fashion Life Cycles—Principles and Perspectives. Journal of Marketing, 45(4), 116–124. doi:10.1177/002224298104500415.

[5]. Cosma, A. (2021). New York, San Francisco and Los Angeles: A Cultural Map of the Beat Generation. Linguaculture (Iași), 12(2), 19–31. doi: 10.4773/lincu-2021-2-0214.

[6]. Jennings, T. (2008). Shades of Chanel. Clothing and Textiles Research Journal, 26(1), 91–93. doi:10.1177/0887302x07305572.

[7]. Nhật,M. (2021). Inside Le Smoking, The First Suit for Women from Yves Saint Laurent. L’officiel Singapore. https://www.lofficielsingapore.com/fashion/yves-saint-laurent-le-smoking-the-first-suit-for-women-from.

[8]. McNeill, L. S. (2018). Fashion and women’s self-concept: a typology for self-fashioning using clothing. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management: An International Journal, 22(1), 82–98. doi:10.1108/jfmm-09-2016-0077.

[9]. Dabral,A. (2019). How Yves Saint Laurent’s Le Smoking suit revolutionised women’s fashion. Lifestyle Asia. https://www.lifestyleasia.com/ind/style/ysls-le-smoking/.

[10]. Kapferer, J.N. (2004), The New Strategic Brand Management: Creating and Sustaining Brand Equity Long Term (3rd ed.). London, U.K. : Kogan Page.

[11]. K.L. Keller, “Managing Brands for the Long Run: Brand Reinforcement and Revitalization Strategies,” California Management Review, 41/3 (Spring 1999): 102-124. doi:10.2307/41165999 .

[12]. Belk, Russell W. (1988), “Possessions and the Extended Self,” Journal of Consumer Research, 15 (September), 139–168. https://doi.org/10.1086/209154 .

[13]. Escalas, J. E., & Bettman, J. R. (2005). Self‐Construal, Reference Groups, and Brand Meaning. Journal of Consumer Research, 32(3), 378–389.

[14]. Berger, J. A., & Heath, C. (2007). Where Consumers Diverge from Others: Identity Signaling and Product Domains. Journal of Consumer Research, 34 (2), 121-134. http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/519142.

[15]. Lynch, L., Patterson, M., & Ní Bheacháin, C. (2020). Visual literacy in consumption: consumers, brand aesthetics and the curated self. European Journal of Marketing, 54(11), 2777–2801. doi:10.1108/ejm-01-2019-0099.

Cite this article

Ding,J. (2023). Fashion, the Self and the Free Spirits. Communications in Humanities Research,11,185-190.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Educational Innovation and Philosophical Inquiries

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Holt, D. B. (2004). How brands become icons: The principles of cultural branding. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

[2]. Berthon, P., Pitt, L., Parent, M., & Jean-Paul Berthon. (2009). Aesthetics And Ephemerality: Observing And Preserving The Luxry Brand. California Management Review, 52(1), 45–66. doi:10.1525/cmr.2009.52.1.45.

[3]. Jang, S. E. . (2007). A study on the clothing styles of renaissance and baroque focused on H.Wolfflin`s Methodology. The Journal of the Korean Society of Costumes, 57(7), 15-29.

[4]. Sproles, G. B. (1981). Analyzing Fashion Life Cycles—Principles and Perspectives. Journal of Marketing, 45(4), 116–124. doi:10.1177/002224298104500415.

[5]. Cosma, A. (2021). New York, San Francisco and Los Angeles: A Cultural Map of the Beat Generation. Linguaculture (Iași), 12(2), 19–31. doi: 10.4773/lincu-2021-2-0214.

[6]. Jennings, T. (2008). Shades of Chanel. Clothing and Textiles Research Journal, 26(1), 91–93. doi:10.1177/0887302x07305572.

[7]. Nhật,M. (2021). Inside Le Smoking, The First Suit for Women from Yves Saint Laurent. L’officiel Singapore. https://www.lofficielsingapore.com/fashion/yves-saint-laurent-le-smoking-the-first-suit-for-women-from.

[8]. McNeill, L. S. (2018). Fashion and women’s self-concept: a typology for self-fashioning using clothing. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management: An International Journal, 22(1), 82–98. doi:10.1108/jfmm-09-2016-0077.

[9]. Dabral,A. (2019). How Yves Saint Laurent’s Le Smoking suit revolutionised women’s fashion. Lifestyle Asia. https://www.lifestyleasia.com/ind/style/ysls-le-smoking/.

[10]. Kapferer, J.N. (2004), The New Strategic Brand Management: Creating and Sustaining Brand Equity Long Term (3rd ed.). London, U.K. : Kogan Page.

[11]. K.L. Keller, “Managing Brands for the Long Run: Brand Reinforcement and Revitalization Strategies,” California Management Review, 41/3 (Spring 1999): 102-124. doi:10.2307/41165999 .

[12]. Belk, Russell W. (1988), “Possessions and the Extended Self,” Journal of Consumer Research, 15 (September), 139–168. https://doi.org/10.1086/209154 .

[13]. Escalas, J. E., & Bettman, J. R. (2005). Self‐Construal, Reference Groups, and Brand Meaning. Journal of Consumer Research, 32(3), 378–389.

[14]. Berger, J. A., & Heath, C. (2007). Where Consumers Diverge from Others: Identity Signaling and Product Domains. Journal of Consumer Research, 34 (2), 121-134. http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/519142.

[15]. Lynch, L., Patterson, M., & Ní Bheacháin, C. (2020). Visual literacy in consumption: consumers, brand aesthetics and the curated self. European Journal of Marketing, 54(11), 2777–2801. doi:10.1108/ejm-01-2019-0099.