1.Introduction

The trend of globalization is accelerating and the demand for interpreters is increasing due to the communication between different cultures. As an important part of interpretation, interpreting notes are essential to interpreters' success in interpreting, and it is also a major problem for beginners. Interpreting studies have now entered an interdisciplinary stage, so it is not enough to study the interpreting notes only at the level of the experience of the practitioners or learn it as established formulas. This paper will use the schema theory, which has received much attention in the field of cognition and psychology, to propose an improvement for interpreting notetaking.

Schema theory originated from German philosopher Kant in 1781 and has been widely applied to English teaching activities: The relationship between schema theory and reading comprehension is explored, followed by effective ways of using schema theory to improve the effectiveness of reading in English, as well as reflections and implications of schema theory for English reading teaching. In writing, the application of schema theory to university English teaching can improve the quality and efficiency of university students' English writing by activating students' existing "schemas" and helping them to create new "schemas". The use of schema theory in the teaching of English at the university level improves the quality and efficiency of students' English writing by activating students' existing 'schemas' and helping them to create new ones. However, in the field of interpreting, schema theory has been used less often, especially in the field of notetaking. Therefore, in this paper, I will introduce three types of schemata: linguistic schema, content schema, and formal schema to enhance note-taking skills in interpreting. Here you should introduce your research questions! What are your research questions?

2.Literature Review

2.1.Consecutive Interpreting note-taking

So far, interpreting studies have entered their fourth period: the renewal period, and the previous three periods are:1. pre-research period, 2. experimental psychology period, 3. practitioners’ period.[1] Regarded as the turning point of interpreting studies, the interpreting conference organized by the University of Trieste in Italy in 1986 began today’s new era of interpreting studies. this present period openly questioned and challenged the perspectives, and theories from the third one, and broke down barriers between different academies, allowing interpreting studies to move from isolated studies among schools into an interdisciplinary, multi-perspective research period, which is the most popular perspective in interpreting studies today.

Since the first period, the study of interpreting training has been a popular research topic. In addition to the training of interpreters' mastery of language, note-taking has been one of the main focuses of the training sessions. Jean François Rozen's book La prise de notes en interprétation consécutive on the basic principles and methods of consecutive interpreting and note-taking is still widely accepted today, Franz Pöchhacke also regarded notes as the interpreter’ s “memory trigger”, associating the input with the output. Professor Daniel Gile as a representative scholar of interdisciplinary empirical research, he concerned with consecutive interpreting as a two-separate-phased cognitive process: (1) the comprehension phase (listening and note-taking phase), (2) the speech production (reformulation phase). In the first phase: Interpreting = L + N + M + C, where N stands for note; in the second phase: Interpreting = Rem + Read + P + C, the “Read” here stands for note-reading.[5] So we can see that without the help of notes, it is hardly possible for an interpreter to successfully reformulate the source language in the target language.

However, there is no concept of a "note-taking system" in academic research. In practice, however, there are some general guidelines. Some EU interpreters and AIIC members deemed note-taking as a system of one's own that they are comfortable with. A note-taking system is an unfixed, constantly developing system. When facing this relatively open system, most interpreting novices encounter various difficulties. For instance, what to note down, improper information noting, and bad note formatting. At first sight, it seems like low language proficiency accounts for note-taking difficulties, but interpreting is regarded as “ a cognitive process, or rather, a complex set of the cognitive processing operation”[3] which makes the problem of interpreting note-taking related to students' mindset and cognitive mechanism.

2.2.Schema Theory

2.2.1.Definition of Schema

The schema theory has become a popular topic in modern cognitive linguistics and has been used extensively in the field of second language acquisition, mainly to guide the study of listening and reading models. It also provides a new perspective for the interpretation study. First introduced by Immanuel Kant in Critique of Pure Reason, who argued that concepts have no meaning on their own, but only when people combine their experience and existing knowledge with them. This was the original concept of schema. A series of experiments conducted by F.C.Bartlett were considered the great leap of schema theory, he described schema as "an active organization of past reactions, or of past experiences, which must always be supposed to be operating in any well-adapted organic response".[4] Later, the schema was introduced in reading by Rumelhal, Carrell, and Hudson when discussing the importance of background knowledge in reading comprehension.

Carrell and Eisterhold wrote that language comprehension relied largely on the readers' background knowledge.[9] The text does not have meaning by itself; rather, it gives instructions on what prior information is required to deduce meaning from the text. The previously gathered information is referred to as schema. and the previously acquired knowledge structures are called schemata [6]. Rumelhart and Ortony proposed that "schema represents stereotypes of concepts".[6] Anderson and Pearson further explained that a schema is an abstract knowledge structure. It is abstract in the sense that it summarizes what is known about a variety of cases that differ in many particulars. It is structured in the sense that it represents the relationship among its component’s parts.

The center of this concept is always: "A schema is a way in which each person's past knowledge is stored in the mind, the brain's response to experience or the active organization of the past memory, and the framework of the learner's previously acquired knowledge". Everyone, consciously or unconsciously, uses "schema" to understand and interpret the objective world. Schema theory assumes that any linguistic material, whether oral or written, is itself dependent on what the listener or reader already knows, i.e., that people need to relate new things to known concepts and past experiences in order to understand them. The understanding and interpretation of something new depend on schemata that already exist in the mind, and the input must match these schemata.

2.2.2.Information Processing Model of Schema Theory

Schema theory suggests that when receiving new information, the human brain does not isolate itself from receiving the new information, but rather the brain takes the information originally stored in the brain, or background knowledge, interacts with the new information, and thus acquires it. This process triggers two modes of information processing, “bottom-up” and “top-down” processing modes.[9] The bottom-up processing mode means that the new knowledge input reacts with the original knowledge stored in the brain and leads to the awakening of higher-level knowledge. The top-down processing mode is the brain's overall processing of information from a macroscopic perspective, and the overall grasp of the information. The top-down information processing mode is the brain's overall grasp of information from a macro perspective. " Bottom-up model ensures that the listener or reader is aware of new information or information that is inconsistent with one's own hypothesis about the content or structure of the text. Top-down helps the listener or reader to resolve doubts or to make decisions in the possible interpretation of the input data.

2.2.3.Three Types of Schema

Schema is suggested into three types: formal schema, content schema, and linguistic schema[10]. Formal schema refers to“background knowledge about the formal, rhetorical, organizational structures of different kinds of texts” formal schema is “abstract, encoded, internalized, coherent patterns of meta-linguistic, discoursed, and textual organization that guide expectations in our attempts to understand a meaningful piece of language”[9].

Content schema is the background knowledge of an essay or the topic it relates to.It includes conceptual knowledge or data about typical knowledge or information within a given topic and how knowledge or information connects to one another to produce a cohesive whole [11]. It is an unrestricted collection of typical people, places, and things for a certain situation. Content schema is especially culture-centered, so the cultural schema is usually counted as content schema.

Linguistic schema refers to readers’ prior linguistic knowledge, namely one’s language proficiency. It includes grammar, vocabulary, and phonetics. For interpreters, a linguistic schema is what they need to master at the very beginning to decode the source language.

3.Schema and Consecutive Interpreting Notetaking

As mentioned before, there are three major schemas in schema theory: linguistic schema, content schema, and formal schema, which are essentially based on known knowledge and formed in the process of interacting with new knowledge. Interpreting notes are also formed in the process of accumulation over time. The prerequisite for the success of notes is the correct understanding of the information. When the source language information enters the brain, it activates the interpreter's own reserved schema: the linguistic schema will promptly interact with the new information and find the best association with vocabulary, phonetics, and other language basics, thus ensuring the accuracy of cognitive understanding of language information in the "bottom-up" information processing method, but it is not enough to obtain an accurate language schema through association. However, it is not enough to obtain accurate linguistic schemata through correlation. Only after understanding and compiling the content schema (cultural schema) in the source language can the interpreter reconstruct the relevant cultural schema in the incoming language and then combine it with the linguistic schema to accurately understand the source language and the speaker's intention. The formal schema stored by the interpreter also helps him/her to predict the discourse characteristics and contextual logic of the source language information, change the passive acceptance of information to active predictive listening and discernment, and "top-down" processing of information, thus reducing the cognitive load of the interpreter. The complementary roles of the three major schemas in the process of inputting and encoding of interpretation are also applicable to the stage of storing information in the notes of interpretation. Based on a full understanding of the source language, the interpreter no longer needs to record all the information as in the case of shorthand or conference notes. Instead, he/she will fully mobilize the content schema of the interpreting note symbols in the brain, and then selectively record the key information by combining the features of the source language and the structural schema of horizontal and vertical logical relationships, thus saving time and energy and reserving more energy for the output of the target language.

3.1.Linguistic Schema in Note-taking

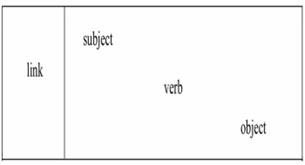

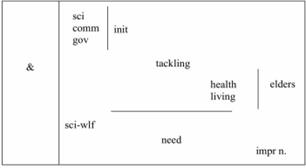

Linguistic schema is traditionally considered the most basic element to learn a second language, such as grammar, vocabulary, and phonetics. After mastering vocabulary and phonetics, the interpreter must also have a good grammatical foundation to be able to quickly find the main stem of a sentence such as subject-verb-object, and the branch of a sentence such as definite article-complement in long and difficult sentences. Sometimes speakers also use emphatic sentences, inverted sentences, and subjunctive moods to emphasize the implication, which means that the interpreter must have very strong basic language skills. When taking notes, the structure of the notes can be planned according to the sentence structure left to right, top to bottom. (See Figure 1. and Figure 2.)Figure 1 is only an example of the simplest sentence structure, and the rest of the structure can be recorded in different ways depending on the interpreter's personal preferences. Figure 2 is a detailed addition to the information in Figure 1, with the same structure, where the vertical lines are used to indicate juxtaposition and the horizontal lines indicate the end of an information segment. These are only a sorting out of the information hierarchy, which is not yet highly symbolic.

Figure 1: Note Structure of an SVO sentence.

Figure 2: Detailed extension of SVO.

Splitting and arranging the structure of the utterance facilitates the interpreter's understanding of the utterance and enables more rapid and accurate conversion of the source language into the target language.

The linguistic schema can also be used in notetaking in two ways. 1. consonant. English as a spelling language, the interpreter will find after a systematic study of phonetics that consonants are the important factor in identifying words rather than vowels. Therefore, when hearing “dinosaur”, interpreters need only record “dns”, which can easily activate the short-term memory when looking back at the notes. 2. Acronym. This method is used more often when encountering phrases, such as “as soon as possible” which can be shortened to “ASAP”. This depends on the interpreter's proficiency in the phrase.

3.2.Content Schema in Note-taking

Content schema refers to the background knowledge and cultural meaning related to the subject matter of the interpretation. The information received by the interpreter in the original language should activate his or her content schema to better understand the source language. There are content schemas for various fields, including politics, economics, health care, art appreciation, auto parts, media communication, etc. If the interpreter has a rich content schema, he or she will be able to predict, analyze and process the information he or she hears during the interpretation process. After understanding the background knowledge related to the interpretation topic, one can formulate the symbols of the abbreviations of the topic words or related words that may appear in advance and write them down in your notebook as a cheat sheet to avoid confusion and repeated usage of symbols at the interpreting site that may lead to jams. This is the help of content schema for interpretation notes during the pre-task preparation.

During interpreting, for instance from English to Chinese, "Sir Lindsay Hoyle has been elected by MPs as the new Commons Speaker after previous Speaker John Bercow stepped down.” in the passage, if the interpreter possesses enough content schema of the British political system, he would immediately equate Speaker to议长(the presiding officer of the House of Commons), not anything like 发言人(addresser). “Lindsay and John” are enough to trigger the memory of the whole sentence, so one only needs to write down “John→Ldsy” in their notepads. This undoubtedly saves time, reduces the burden of interpreting, and provides a good guide for the extraction of information in the target language expression.

3.3.Formal Schema in Note-Taking

Formal schema refers to the linguistic structure, rhetorical devices, and composition of a discourse. Good knowledge of formal schema can greatly assist the interpreter to understand the speaker's intention and structure of speech. For narrative discourse, the 5W1H formal schema in the mind can be fully mobilized to aid comprehend and process the information in a top-down way, so that all that needs to be written down in the notes are the keywords that can stimulate the relevant schema in the brain, and these keywords can be further simplified into symbols. Not all the information points should be taken down as notes, but the key points and the general structure of the information are often noted down, except for proper nouns and connecting words, an interpreter should fathom the implication of the speaker’s words. Sometimes speakers may use some rhetorical techniques to express themselves, so the interpreter's formal schema must come in handy to quickly understand these rhetorical techniques and note down the true meaning instead of copying the original text as it is, to reflect what the speaker thinks in the target language and reduce the risk of misinterpreting and omission, which may lead to distortion of the speaker's meaning or incomplete understanding by the audience.

4.Conclusion

I take schema theory as an entry point and briefly analyze and discuss its application in this paper briefly analyzes and discusses its application in interpretation note-taking. Linguistic schema, content schema, and formal schema all interact with each other in interpreting notes: they help interpreters to judge the meaning of words and to avoid the risk of being overlooked. The linguistic schema, content schema, and structural schema all interact with each other in interpreting notetaking: they help interpreters to judge the meaning of words and avoid ambiguity; help interpreters make positive predictions and improve and help to reduce the memory load of the interpreter and to allocate their energy rationally. It also helps to reduce the memory load of the interpreter and allocate the mental energy appropriately. Therefore, students who are new to interpreting, need to enrich their linguistic, content, and formal schemas during their study. It is especially important to improve the accuracy and recording efficiency of interpreters' notes.

Author’s Contributions

To date, studies that have used schema theory to explore the relationship between background knowledge and foreign language learning have focused on the fields of reading and listening. In recent years, schemas have also provided a macroscopic view of translation from the fields of philosophical and psychological information and culture, opening up a new theoretical course. Schema theory has been invoked in translation studies from different perspectives in psychology, language, linguistics, and culture, but most of studies have focused on text translation, there are few applications of schema theory to interpreting. Interpreting is seen as a skill that relies on memory and good language skills and requires long hours of practice, but inspired by current interdisciplinary research on interpreting, I have applied schema to interpreting note-taking to develop a systematic method of practicing interpreting note-taking that is applicable to most people. Although not theoretically innovative, the application of schema theory to interpreting note-taking in this paper can provide interpreters with a new way of thinking about note-taking. In this method, interpreters can generate their own appropriate interpreting note-taking style based on their own knowledge and reduce their memory workload, rather than the traditional dogmatic rules that need to memorize the by rote.

Acknowledgements

First of all, I would like to thank my paper mentor, Yujing Su for her guidance from the first lesson on how to organize a paper to the final comments on how to revise the paper. Secondly, I sincerely appreciate Professor Andrew for opening the door to a new world for me with a course so professional and at the same time easy to understand. Certainly, our teaching assistant Yunchong Huang is genuinely responsible, for reviewing our knowledge every Sunday and answering all my questions in detail.

I am also very grateful to CIS for giving me the opportunity to get involved in this programme. I have gained a lot from the nearly three months of study and developed new insights into academic research. The teachers who worked behind the scenes are absolutely worth my gratitude. Lastly, I would like to express my gratitude to the various literature repositories, especially Google Scholar, which has helped me to find a lot of literature. Thank you to Professor Daniel Gile, who is a very prolific scholar in the field of interpreting and whose research has been very inspiring to me.

Although the whole process was not particularly smooth, with the help of all the above people and things, this paper was finally completed.

References

[1]. D. Gile, The history of research into conference interpreting, in:Target, International Journal of Translation Studies 12 (2) 297–321. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1075/target.12.2.07gil

[2]. D. E. Rumelhart, Schemata: the building blocks of cognition, in: R. J. Spiro, B. C. Bruce, W. F. Brewer (Eds.), Theoretical Issues in Reading Comprehension, Routledge, London, 2017, pp. 26. DOI: https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315107493

[3]. F. Pöchhacker, Interpreting Studies. In: Y. Gambier, L.van Doorslaer (Eds.), Handbook of Translation Studies, John Benjamins Publishing Company, Amsterdam/Philadelphia, 2010, pp. 158–172. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1075/hts.1

[4]. F.C. Bartlett, Remembering: A Study in Experimental and Social Psychology.Cambridge University Press, 1932, pp. 201

[5]. D. Gile, The effort models of interpreting, in D. Gile (Eds.), Basic Concepts and Models for Interpreter and Translator Training. John Benjamins Translation Library, 2009, pp. 175-179.

[6]. D. E. Rumelhart, Toward an interactive model of reading, in: Attention and performance VI, Routledge, London, 1977, pp. 573-603. DOI: https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003309734

[7]. B.B. Armbruster, Schema theory and the design of content-area textbooks, in: Educational Psychologist, 21(4) (2010): 253–67.DOI: https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326985ep2104_2

[8]. An Shuying, Schema theory in reading, in: Theory and Practice in Language Studies, ACADEMY PUBLISHER, Finland, 2013, pp. 130-134. DOI: https:/doi.org/10.4304/tpls.3.1.130-134

[9]. P.L. Carrell, J.C. Eisterhold, Schema Theory and ESL Reading Pedagogy, in: TESOL Quarterly 17(4) (1983) 553-573, DOI: https:/: doi.org/10.2307/3586613

[10]. P.L. Carrell, Evidence of a formal schema in second language comprehension, in: Language Learning, 34(2) (1984) 87-108, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-1770.1984.tb01005.x

[11]. P.L.Carrell, Some causes of text-boundedness and schema interference in ESL reading, in: P. L. Carrell, J. Devine, D.E. Eskey (Eds.), Interactive Approaches to Second Language Reading. Cambridge University Press, 1988, pp.101-113. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139524513.012.

Cite this article

Chen,R. (2023). Schema Theory in Consecutive Interpreting Note-taking. Communications in Humanities Research,2,611-617.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Educational Innovation and Philosophical Inquiries (ICEIPI 2022), Part III

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. D. Gile, The history of research into conference interpreting, in:Target, International Journal of Translation Studies 12 (2) 297–321. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1075/target.12.2.07gil

[2]. D. E. Rumelhart, Schemata: the building blocks of cognition, in: R. J. Spiro, B. C. Bruce, W. F. Brewer (Eds.), Theoretical Issues in Reading Comprehension, Routledge, London, 2017, pp. 26. DOI: https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315107493

[3]. F. Pöchhacker, Interpreting Studies. In: Y. Gambier, L.van Doorslaer (Eds.), Handbook of Translation Studies, John Benjamins Publishing Company, Amsterdam/Philadelphia, 2010, pp. 158–172. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1075/hts.1

[4]. F.C. Bartlett, Remembering: A Study in Experimental and Social Psychology.Cambridge University Press, 1932, pp. 201

[5]. D. Gile, The effort models of interpreting, in D. Gile (Eds.), Basic Concepts and Models for Interpreter and Translator Training. John Benjamins Translation Library, 2009, pp. 175-179.

[6]. D. E. Rumelhart, Toward an interactive model of reading, in: Attention and performance VI, Routledge, London, 1977, pp. 573-603. DOI: https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003309734

[7]. B.B. Armbruster, Schema theory and the design of content-area textbooks, in: Educational Psychologist, 21(4) (2010): 253–67.DOI: https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326985ep2104_2

[8]. An Shuying, Schema theory in reading, in: Theory and Practice in Language Studies, ACADEMY PUBLISHER, Finland, 2013, pp. 130-134. DOI: https:/doi.org/10.4304/tpls.3.1.130-134

[9]. P.L. Carrell, J.C. Eisterhold, Schema Theory and ESL Reading Pedagogy, in: TESOL Quarterly 17(4) (1983) 553-573, DOI: https:/: doi.org/10.2307/3586613

[10]. P.L. Carrell, Evidence of a formal schema in second language comprehension, in: Language Learning, 34(2) (1984) 87-108, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-1770.1984.tb01005.x

[11]. P.L.Carrell, Some causes of text-boundedness and schema interference in ESL reading, in: P. L. Carrell, J. Devine, D.E. Eskey (Eds.), Interactive Approaches to Second Language Reading. Cambridge University Press, 1988, pp.101-113. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139524513.012.