1.Introduction

World’s languages are divided to different language families, tools for division (what’s tools for division?) and origination. To be more specific, language study itself includes comparisons and contrasts which lead to the discovery of difference between languages. Swahili is a Bantu language and the second widely used African language after Arabic. Though there has still been a discussion of the origins of Swahili, it is said that “evidence from linguistic research showing that Swahili is a Bantu language”. Considering the lack of study on Bantu languages compared to English. This study will provide a comparison of modern Swahili and English on simple past tense.

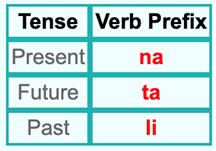

Before we dive into grammar introduction, we will define several aspects. First, Kiswahili is the native name of Swahili language (or just Swahili) and the native language of WaSwahili, meaning local Swahili people. Second, Swahili past tense includes subject prefix, and the past tenses are different in positive and negative forms. Third, Swahili language now mainly consists of three tenses: past tense, present tense and future tense. All three aspects are the background of this paper, a study on Swahili and English’s simple past tense.

Standard Swahili follows the hodiernal tense which refers to events of earlier today (or earlier than the reference point of the day under consideration). Past tense in Swahili is different from the past tense in English which has a clear structure based on time accords. The difference between standard Swahili and English includes definition of past tense, mainly focusing on past tense, sentence structures and words change; and environments these past tenses are used.

Through English perspective, we can find a language which focuses on word order freedom but lacks tone difference. Sentence structures in both languages differ, but under the same tense immerse commonalities. In simple past tense, the most obvious thing is SVO structure. The history of how past tense transfer, historical relationship between Swahili and English past tense are all hard to trace.

This paper is studying Standard Swahili and English through typological view.

2.Morphology in Swahili and English

It is important to know that time is not “inherently portioned” [1] but are defined by time restrictions or time points. Tense varies mainly due to the speech act. Past, present and future tenses refer to events happened before, during and after this speech act. Tense is invented to express events happening on a timeline [2,3]

Tenses do not have clear definitions since according to strict definitions, the present tense should be used to describe events happening just within the speech section. Any events happened before speeches are defined as past tense, similarly, events which have the possibility or be predictable to happen after the speech should use future tense.

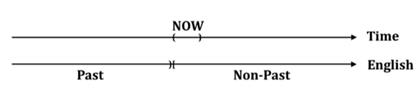

Many languages therefore only differentiate PAST/NON-PAST or NON-FUTURE/FUTURE and incorporate the present in NON-PAST or NON-FUTURE, respectively [1].

Bantu languages are known for its clear definition on time points. [1,4,5]

3.Clarify simple past tense in Swahili

Swahili has five major tenses: past, present, future, past perfect, and habitual tense. Each tense has different applications and different markers, but each marker refers to only one application. This makes their TAM systems rough and complicated. In D Rieger’s paper, he analyzes TAM system by dividing markers to three groups: “present”, “non-present” and “modal” [1]. The author lists markers, tenses, references used for translating to other languages, and examples to specify application environments.

In the second past “non-present”, there are two standard Swahili past tenses: Remote Past and Proximate Past [1]. As stated, the author uses references to translate tenses in Swahili to other languages, helping readers to understand. One of the citations is from “M. A. Mohammed’s grammar” [1], expressing that “Remote Past” refers to “simple past tense” in English and “Proximate Past” refers to “present perfect tense” [1,6].

3.1.Remote Past in Swahili

Remote Past in Swahili includes remarks a) –li- and b) –ku-.[4] This is also shown below [7].

Figure 1: Remote Past in Swahili

According to D Rieger’s paper and a video from YouTube, the basic sentence structure can be concluded as: personal pronouns, subject prefix, tense markers, verbs/nouns.[3]

It should be noticed that Swahili can also be divided into two types: positive and negative. Tense marker “–li-” is applied when the attitude is positive; “–ku-” means negative. [3,8] Some state these two attitudes as “affirmative and negative” (this expression will be used in English description afterwards)[8].

Theory Part 1

I will give three examples presented in the video to show the difference between these two tense markers. The results will be enough to show the grammar sequence instead of proving the results in an actual and concise way.

1)Swahili: Mimi nilisoma kitabu.

English: I read a book.

2)Swahili: Mimi sikusoma kitabu.

English: I didn’t read a book.

3)Swahili: Mimi nilicheza mpira.

English: I played a ball. [3]

Comparing example 1 and 2 gives: The change in attitude changes the tense markers “–li-” and “–ku-”. The subject prefixes determine attitudes whether to be positive or negative.

Comparing example 1 and 3 gives: Under same attitude, the subject prefix “-ni-” follows the personal pronouns “mimi” which means “I”.

Comparing example 2 and 3 gives: The subject prefixes following the same personal pronoun will differentiate under two attitudes. “si” is the negative form of “ni” while only been used with “mimi”, expressing “I”.

Conclusion: Personal pronouns, verbs/nouns do not change. Past tense markers and subject prefixes change with attitudes. Each subject prefixes follows only one personal pronouns in one attitude. Each past tense markers follows all subject prefixes in one attitude.

This conclusion is detailed explained in another video. Cite here as [9].

Theory part 2 [10]

Based on former theories, now we extend to more details about verb changes.

It is important to notice the difference between English and Swahili. Swahili verbs do not add additional past-participle suffix due to tenses, instead they change the tense markers.

There are two types of verbs in Swahili, one from the Bantu origin and the other from the Arabic origin, named as type 1 and type 2. The one from the Bantu origin also have two kinds, named as type 1.1 and type 1.2.

Type 1.1: Kunywa Kuja Kupa Kula

Type 1.2: Soma Enda Lala Pika Nunua

Type 2: Fikiri Subiri Jaribu Samehe

Words in type 1.1 are monosyllabic: nywa, ja, pa, la. They compound with infinitive “ku”. These words’ translation to English will include “to”, as to become infinitives. For example, “kunywa” means “to bring” and “kuja” means to come.

Words in type 1.2 are non-monosyllabic: soma, enda, lala, pika, nunua. They are simple verbs. For example, “soma” means “read”. “enda” means “go”.

All Bantu origin words in Swahili are ending with vowel “a”. While all Arabic originated words end with “i”, “u” and “e”, as we can see in words: fikiri, subiri, jaribu, samehe. [10]

3.2.Proximate Past Tense

Proximate past tense is called as “past tense” in Swahili, but it is not in English. The tense marker is “–me-”. So proximate past tense equals to “me” tense in Swahili.

Here is a conflict on which should “Proximate past tense” be translated to in English. It is stated to be “present perfect tense” [4-6,8,9]. But some claim this as “past perfect tense”.[11,12] The proximate past tense has the same meaning as “present perfect” tense in English, not the past perfect tense.

There is another question which still requires further investigation. “-me-” “is always used with the positive verbs.” “-ja-” is used when the attitude is negative. However, this pattern is not mentioned in paper [4]. The “-ja-” tense is representing “not yet”, which cannot be strictly related with past tense.[9] We will skip the discussion about “-ja-”.

This “-me-” tense will be extended and explained since the “present perfect” does not exactly exist in English and it is considered as “past tense” in Swahili. [9] The vagueness in Bantu languages still make the definitions of tenses to become hard. In short, “me” tense includes “have done” and “be used to do” in English.

We can group “-me-” tense based on verbs into two categories: passive verbs and active verbs.

3.2.1.Passive verbs

Using positive passive verbs indicates “is currently in the state of” [9]. Hence, these verbs are to express the states of objects.

Example:

Swahili: amepotea

English: He is lost.

Lost is the status, -me- refers to this rule. “This is similar to saying ‘he is currently in the state of being lost at this moment.’[9].

3.2.2.Active Verbs

This is a confusing part if we consider it from English view. The basic form of active verbs -me- tense is “have done” in English. To just consider the form of “have done”, it shall be stated as present perfect tense, the same as the passive words. However, this should be defined as past perfect in English. For example, "He ran" vs. "He has run". The "have + run" form is the Past Perfect since it is referring to the time before the happened events.[13]

Hence, active verbs in -me- tense in Swahili are past perfect tense rather than present perfect.[13] In my view, there should still be discussion about this because I also find “present tense for active verbs in -me- tense” examples. [11,13]

4.Clarify simple past tense in English

English has three tenses: past, present and future. But future tense is not considered as a tense in Linguistics.

“English lacks a morphological future tense, since there is no verb inflection which expresses that an event will occur at a future time.”[14]

According to TAM system, tense-aspect-mood, English has 12 verb tenses. Three basic tenses and four main aspects: simple, perfect, continuous (also known as progressive), and perfect continuous.

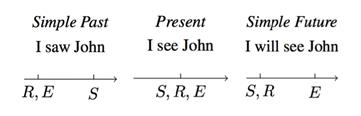

The time reference in English has formed different systems to explain. I will introduce a system created by Reichenbach. This model of tense is able present every tense with three time points: E, R, and S. [15,16] Each means Event Time, Reference time and Speech time.

Past: E, R_S (e.g., She was at home yesterday; R = yesterday).[17]

A picture used to explain ERS system is as below. [15]

Figure 2: ERS system.

When Events time precedes Speech time, Reference time precedes Event time, it refers to simple past tense. To be more clarified, people refer to events happening before the time they speak. It will be harder if four aspects in English are all considered, but simple past tense in English is valued for its conciseness.

For the sake of the whole English tense system, we can define it as Past and non-Past. This distinction proposal is consistent due to “Basic Time Concept”. In Linguistical explanation, time displays the characteristics of segment ability, inclusion and linear order.[15]

Figure 3: linear order.

Hence, past tense is clearly defined as events finishing at or before the period “now”. But present and future are not as distinct as past tense do.

Figure introduces verbs change, sentence structures and other characteristics of English simple past.

4.1.Simple Past in English

Simple past tense is also called past indefinite or past simple in Modern English. Regular verbs for the simple past time end with -ed, but a few hundred special verbs have irregular forms.

At the first step, the fixed sentence structure of simple past tense is Subject + Verb + Object, the basic and the most well-known sentence structure in English. To specify, SVO structure satisfies affirmative base form. Comparatives between affirmative and negative, and declarative and negative cause difference. All situations are listed below.

POSITIVE FORM (+): Subject + V2 (Second Form of Verb)

NEGATIVE FORM (-): Subject + did not + V1 (First Form of Verb)

QUESTION FORM (?): Did + Subject + V1 (First Form of Verb)

SHORT ANSWER FORM ( + / – ) : YES / NO + Subject + did / did not (didn’t) [18]

Definition 1: First, second and third form of verbs refers to base form, simple past tense and past participate.

Definition 2: Auxiliary verbs include “did and did not”. Auxiliary verbs are not allowed to use in positive sentences while the second form of the verb is used. [19] Except for Expanded (emphatic) simple past, but here “did” is used for emphasizing existing truth.

Sentences have basic structures, but objects, places, time words and sequences can still be added and changed.

1)Question words are used in past tense.

Question Words (who, what, why, etc.) + did + subject pronoun (he, she, it, I, you, we, they) + V1 ( First Form of Verb )

Example: Where did you go last night?

What did you do yesterday?

Auxiliary word do is unavoidable in this situation. [19]

2)Simple past use for a past single event, past habitual events and past state. On the basis of past tense sentence structures, complements (C) exist.

Example: He robbed the bank and escaped.

I ate my dinner at Daniel’s for a year.

I knew how to go to the temple. (Past state)

3)When we are describing on going events states, past progressive is used as common substitution. However, there are six common states for past tense: know, believe, need, love, dislike, prefer which use simple past tense. Some additional verbs like have, own, hear or the others rejects progressive tense. “To explain, in these cases the simple past is used even for a temporary state.” [20]

4)When one action is interrupted, “it is usual for the interrupted (ongoing) action to be expressed with the past progressive, and the action that interrupted it to be in the simple past.” [20]

Example: My brother came in while I was playing games.

Notice came and was playing.

5)Due to the proximate past in Swahili, we have to make a clarification between simple past and present perfect in English. Past tense in English describes of events happened in the past, or during a period which ended in the past. [21] This ending cannot reach the present time point.

6)Simple past form can be applied without referring to past time. Basically, in conditional clauses or clauses referring to hypothetical circumstances and certain expressions of wish. [21]

Examples: If he finished the project quicker, he would not be blamed.

I wish I knew what happened.

I would rather she wore a longer dress.[21]

5.Compare and contrast

To begin with, English has already formed mature TAM system. This is not referring to the perfectness of any language, but to the comparative “completeness” to Swahili. TAM system in Swahili is clearly clarified, but languages users do not follow rules in a clear way. This difference does not show completely in simple past tense since the structure is still simple to understand and uniform. Also, similar sentence structure satisfies dual languages learners understanding.

Past tense in both languages have strict time points. The main time point for defining present and past is similar, approaching too same. Proximate past in Swahili is similar to present perfect in English and remote past matches simple past in English. The two categories in 3.2.1 and 3.2.2 are pretty confusing, after investigations, this is an unavoidable difference when the original language does not match English. However, present investigation done by me have not concluded the number of simple past tense sentence structures in Swahili (say something like the comparison in this paper has concluded the number ….). The comparison between Swahili and English may have only one definite conclusion: they both follow basis SVO pattern.

There is a theory: Bantu language are famous for their remote distance between past and future. The hodiernal tense in Bantu language is common, but it cannot be found in Swahili. This makes Swahili “being closer” to English.

6.Conclusion

This passage summarizes simple past tense in Swahili and English and delivers a difference. Providing enough information to have brief view of the value of tense study while comparing other languages to English. This study serves tools for dual languages learner well.

There are still other more complicated tenses in both languages remained not compared which have study value, especially for language spreading procedure and coaching use. Studies in Swahili have already built-up strong systems. Hence, I believe comparative studies are required for further study, including historical, phonological and morphological in view of protective and scholar records.

References

[1]. Rieger, Dorothee. "Swahili as a tense prominent language: Proposal for a systematic grammar of tense, aspect and mood in Swahili." Swahili Forum. Vol. 18. No. 2011. 2011.

[2]. Bhat, D. N. Shankara. 1999. The Prominence of Tense, Aspect and Mood. Amsterdam, Philadelphia: John Benjamins

[3]. Michaelis, Laura A. “Tense in English.” The Handbook of English Linguistics, 2020, pp. 163–181., https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119540618.ch10

[4]. Bybee, Joan L., Revere Dale Perkins, and William Pagliuca. The evolution of grammar: Tense, aspect, and modality in the languages of the world. Vol. 196. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994.

[5]. Nurse, Derek, and Gérard Philippson. The bantu languages. Routledge, 2006.

[6]. Mohamed, Mohamed. A. 2001. Modern Swahili Grammar. Nairobi, Kampala, Dar es Salaam: East African Educational Publishers.

[7]. “Swahili Cheat Sheet”, https://www.swahilicheatsheet.com/.

[8]. “Nyakati za Kiswahili/Swahili Tenses”, https://nulib-oer.github.io/swahili/topics/tenses/

[9]. SWAHILI NEGATIVE SENTENCES.BEGINNERS LEVEL.LESSON #6”, YouTube, LEARN SWAHILI WITH PATRICIA, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OA3i6p4oDyI

[10]. “SWAHILI GRAMMAR: PAST TENSE "LI".HOW TO CONSTRUCT A SENTENCE IN SWAHILI?”, YouTube, ABU SWAHILI, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xTzyyCsApHc.

[11]. “Swahili Tenses”, https://www.kwangu.com/swahili/verbs_tenses.htm

[12]. “Swahili Grammar: The tense “me” with “mesha””, YouTube, FC LangMedia, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=k9PHiN8rYnQ

[13]. Chen, Sherry Yong. (2017). Processing Tenses for the Living and the Dead: A Psycholinguistic Investigation of Lifetime Effects in Tensed and “Tenseless” Languages.

[14]. Freeborn, Dennis (1995). A Course Book in English Grammar. Palgrave, London. pp. 149–150. ISBN 978-1-349-24079-1.

[15]. Reichenbach, H. (1947). Elements of symbolic logic. New York: Macmillan.

[16]. Michaelis, L. A. (2020). Tense in English. The Handbook of English Linguistics, 163–181. doi:10.1002/9781119540618.ch10

[17]. “Structure of Simple Past Tense”, author Englishstudy, https://englishstudypage.com/grammar/simple-past-tense-structure/

[18]. “Simple Past”, last edited at 09:18, 27 April 2022; created at 16:21, 1 February 2004, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Simple_past

[19]. “SWAHILI GRAMMAR FOR BEGGINERS: CONSTRUCTION OF SWAHILI PAST TENSE (POSITIVE & NEGATIVE)”, YouTube, LEARN SWAHILI WITH PATRICIA, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1A8BVXJjhjQ

[20]. “Swahili language”, Wikipedia, last edited at 20:22, 7 July 2022, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Swahili_language.

[21]. “Kiswahili.” Edited by Sangai Mohochi and Yussuf Hamad, KISWAHILI, https://web.archive.org/web/20161215022721/http://swahililanguage.stanford.edu/.

Cite this article

Ye,C. (2023). Comparison of Simple Past Tense between Standard Swahili and English. Communications in Humanities Research,2,626-632.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Educational Innovation and Philosophical Inquiries (ICEIPI 2022), Part III

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Rieger, Dorothee. "Swahili as a tense prominent language: Proposal for a systematic grammar of tense, aspect and mood in Swahili." Swahili Forum. Vol. 18. No. 2011. 2011.

[2]. Bhat, D. N. Shankara. 1999. The Prominence of Tense, Aspect and Mood. Amsterdam, Philadelphia: John Benjamins

[3]. Michaelis, Laura A. “Tense in English.” The Handbook of English Linguistics, 2020, pp. 163–181., https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119540618.ch10

[4]. Bybee, Joan L., Revere Dale Perkins, and William Pagliuca. The evolution of grammar: Tense, aspect, and modality in the languages of the world. Vol. 196. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994.

[5]. Nurse, Derek, and Gérard Philippson. The bantu languages. Routledge, 2006.

[6]. Mohamed, Mohamed. A. 2001. Modern Swahili Grammar. Nairobi, Kampala, Dar es Salaam: East African Educational Publishers.

[7]. “Swahili Cheat Sheet”, https://www.swahilicheatsheet.com/.

[8]. “Nyakati za Kiswahili/Swahili Tenses”, https://nulib-oer.github.io/swahili/topics/tenses/

[9]. SWAHILI NEGATIVE SENTENCES.BEGINNERS LEVEL.LESSON #6”, YouTube, LEARN SWAHILI WITH PATRICIA, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OA3i6p4oDyI

[10]. “SWAHILI GRAMMAR: PAST TENSE "LI".HOW TO CONSTRUCT A SENTENCE IN SWAHILI?”, YouTube, ABU SWAHILI, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xTzyyCsApHc.

[11]. “Swahili Tenses”, https://www.kwangu.com/swahili/verbs_tenses.htm

[12]. “Swahili Grammar: The tense “me” with “mesha””, YouTube, FC LangMedia, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=k9PHiN8rYnQ

[13]. Chen, Sherry Yong. (2017). Processing Tenses for the Living and the Dead: A Psycholinguistic Investigation of Lifetime Effects in Tensed and “Tenseless” Languages.

[14]. Freeborn, Dennis (1995). A Course Book in English Grammar. Palgrave, London. pp. 149–150. ISBN 978-1-349-24079-1.

[15]. Reichenbach, H. (1947). Elements of symbolic logic. New York: Macmillan.

[16]. Michaelis, L. A. (2020). Tense in English. The Handbook of English Linguistics, 163–181. doi:10.1002/9781119540618.ch10

[17]. “Structure of Simple Past Tense”, author Englishstudy, https://englishstudypage.com/grammar/simple-past-tense-structure/

[18]. “Simple Past”, last edited at 09:18, 27 April 2022; created at 16:21, 1 February 2004, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Simple_past

[19]. “SWAHILI GRAMMAR FOR BEGGINERS: CONSTRUCTION OF SWAHILI PAST TENSE (POSITIVE & NEGATIVE)”, YouTube, LEARN SWAHILI WITH PATRICIA, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1A8BVXJjhjQ

[20]. “Swahili language”, Wikipedia, last edited at 20:22, 7 July 2022, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Swahili_language.

[21]. “Kiswahili.” Edited by Sangai Mohochi and Yussuf Hamad, KISWAHILI, https://web.archive.org/web/20161215022721/http://swahililanguage.stanford.edu/.