1.Introduction

The film City of Sorrows centers its narrative around the historical event of the “228 Incident”, depicting the helplessness and misery experienced by ordinary people in the face of overwhelming historical forces. The movie starts from the perspective of these ordinary people and gives a poignant portrayal of their struggle. After 50 years of Japanese colonial rule, Taiwan was returned to China after World War II. However, the island’s inhabitants soon found themselves confronted with a new ruling force, the Kuomintang, who were perceived to be even more greedy and oppressive than the previous colonizers. The pejorative terms used in the movie, such as “dog” for the Japanese and “fat pig” for the KMT, vividly reflect the sentiments of the Taiwanese people towards these two occupying forces [1]. A pivotal moment in the consolidation of the concept of a Taiwanese community was the February 28th Incident in early 1947. This tragic event, characterized by violent repression and widespread suffering, further deepened the Taiwanese people’s perception of the KMT regime as a “neo-colonizer.” The KMT’s treatment of the Taiwanese like the abuses suffered by Chinese peoples throughout history (e.g., Kublai’s Yuan dynasty) underscores the sense of injustice and subjugation experienced by the Taiwanese. The film emphasizes the ironic fact that during the Japanese occupation in 1895, Taiwan as a colony was governed under a “rule of law” system. However, when the Kuomintang “recovered” Taiwan in 1945, the Taiwanese found themselves under a “lawless rule” reminiscent of colonial oppression. This stark contrast led many Taiwanese to view Japan’s colonial rule over Taiwan as more tolerable than the KMT’s rapacious rule [2]. Since the seventeenth century, Taiwan has been governed by various powers, including the Dutch East India Company (VOC), the Goldsinger regime, the Qing Empire, the Japanese Empire, the Nanking Nationalist Party (NKP), the immigrant Nationalist Party (NKP) under U.S. protection during the Cold War, and is currently under the influence of the U.S. and the People’s Republic of China (PRC). These powers have repeatedly incorporated and separated Taiwan from their empires, resulting in a state of being caught between empires. This situation has led to the formation and solidification of the community notion in these territories [3].

The focus here is to compare the actions of the colonizers towards Taiwan and how the Taiwanese responded to and perceived these actions during the Japanese rule over Taiwan and the post-war period in Taiwan. The comparison is focused on aspects of cultural colonization and resistance as well as national identity.

2.Cultural Colonization During the Japanese Rule of Taiwan - “Assimilation Policy”

From 1911 onwards, Japan’s attitude toward Taiwan gradually began to shift from exploitation—from viewing Taiwan as the “black factory” of Japan, the “motherland,” to national unification. In response to this series of changes in political system, education and culture, the Japanese Empire issued a series of “assimilation policies”. This “assimilation policy” or “assimilationism” did not derive from the name of the Empire of Japan, but from the example of the colonial policy pursued by the “predecessors” of the Empire of Japan, such as France and Britain. Japan’s assimilation policy in Taiwan has two pillars. First, laws and institutions. The other is modernization and national moral indoctrination. Judging by the content, Japan will stage a “modernization trilogy”. The first is “comprehensive Japanese language education” Japan began to implement comprehensive Japanese language education through various draconian measures as early as 1896. Japanese is considered the basic language of schooling at all levels. The second part is “imperialist education.” Indoctrination from the idea of “subjects of Great Japan”. The Japanese way of life includes customs, religious beliefs, culture and art, seasons and festivals. Abandoning Taiwanese folk beliefs, burning ancestral tablets, and converting to Japanese Shintoism. From the spiritual level to daily life, the people of Taiwan have completely become puppets of the Japanese. The third step is to change the ethnic origin of the people [4]. According to historical records, when Kenjiro Toda was governor, he implemented the “Tainai Marriage Law”, that is, Taiwanese and Japanese intermarriage, in order to assimilate Taiwan through intermarriage between Taiwanese and Japanese. In addition, after giving birth, you can also enjoy local medical treatment in Japan. Japan allows residents of the island of Taiwan to intermarry with Japanese. The aim was to make all islanders descendants of the Japanese. As a result, a large number of mixed-race descendants appeared, and these mixed-race descendants did not return to Japan after the restoration of Taiwan in 1945. It is said that 6 million descendants of Japanese remain in Taiwan. From this “modernization trilogy”, we can find that Japan’s “assimilation” of colonies is actually strictly the pursuit of a kind of “homogeneity”, that is, the pursuit of “heart” loyalty, rather than “assimilation” of colonies. In other words, it seeks inner loyalty, not the notion of “assimilation” or “acceptance” by the ruler [5].

2.1.Cultural Colonization in Post-War Taiwan - “Assimilation Policy”

In 1945, World War II ended with Japan’s defeat and the signing of the Final Order for Japanese Forces in Taiwan. Field Marshal MacArthur issued General Order No. 1 on August 17, 1945, and the first article of General Order No. 1 stipulated that the Japanese forces should report to Chiang Kai-shek, the representative of the Allied Forces. On October 25 of the same year, the ROC general accepted the surrender of Japanese forces in Taiwan on behalf of the Allied Forces. Taiwan remained under Japanese rule from the surrender of Japan on August 15, 1945, until the establishment of the Taiwan Provincial Administrative Office on October 5, 1945. The surrender of Japan on August 15, 1945, the establishment of the Frontier Command Post in Taipei on August 15, 1945, and the emergence of nearly two months of anarchy on October 5, 1945, saw the Japanese forces in Taiwan maintain the system under the original Japanese rule until the Administrator General’s The Japanese forces in Taiwan maintained the system under Japanese rule until the Office of the Chief Executive took over [6, 7]. The Kuomintang government ruled Taiwan for 50 years and conducted anti-Japanese education. In 1956, the Ministry of Education banned the use of Taiwanese (Hokkien) and Hakka) in schools and set up pickets for students to supervise each other; students who spoke Taiwanese “with dog tags” were subjected to corporal punishment, fines, or insults. It also stipulates that public authorities and public utilities can only provide “Chinese services”. But these were very superficial measures in comparison. The assimilation policy during the Japanese colonial period was only to curb the “pro-Japanese sentiments” that permeated the blood through physical and material punishments, which could be said to be more “inferior” and “barbaric” when compared with the behavior of the Kuomintang during its rule over Taiwan, which was a more brilliant strategy of the Japanese Empire, because the Kuomintang, who succeeded Japan in ruling Taiwan, was only using Taiwan as a jumping-off point for its purpose of counter-attacking the mainland, and so they had only a conqueror’s sense of superiority and were not responsible for Taiwan, and their thinking and practices were different from those during the Japanese rule.

Therefore, Table 1 shows the difference in cultural colonization methods between the two different periods. Japan’s “assimilation policy” was implemented in the form of modernization and inculcation of national morality, while Kuomintang’s implementation of Chineseization, anti-communism, and mono-culture was predominant. The different implementation programs contributed to Taiwan’s different attitudes toward the two colonizers.

Table 1: Cultural Colonization: Comparison of the Period of Japanese Rule in Taiwan and the Postwar Period in Taiwan.

phase |

Japanese rule in Taiwan (15th-17th century) |

post-war period in Taiwan |

pursuit of a policy |

assimilationist policy |

Chineseization, anti-communism, monoculture |

A specific program |

Modernization and national moral indoctrination |

mandatory anti-Japanese education |

2.3.Resistance and National Identity - The Japanese Rule Period

Even Taiwan, often praised as the “model pupil” under the Japanese Empire’s “assimilation policy”, also witnessed resistance from its indigenous population. Upon recognizing the Japanese as “foreigners” in Taiwan, these individuals developed their own group identity, feeling a sense of belonging towards a specific nationality or country. As a result, the Taiwanese nurtured a “sense of resistance” against Japan, primarily because they viewed Japan as an oppressor and felt that their identities profoundly differed from that of the Japanese Empire. During the half-century of Japanese rule, the armed anti-Japanese movement was primarily concentrated within the first 20 years. According to extensive scholarly research, the armed resistance against Japan can be broadly divided into three phases. The first phase encompasses the resistance of the Taiwan Democratic State against the Japanese army’s subjugation during the Yiwei War. The second phase unfolded immediately after the Taiwan Democratic State’s formation, with the early anti-Japanese guerrilla warfare marked by armed anti-Japanese actions occurring almost annually. The final phase commenced with the Beipu Incident in 1907 and concluded with the Xilai’an Incident in 1915. Subsequently, Taiwan’s anti-Japanese movement evolved into a non-violent form of resistance, focused on preserving Han culture. Nonetheless, during this period, the Wushe Incident, which gained global attention, still took place [8].

2.3.1.Resistance and National Identity--Taiwan’s Postwar Period

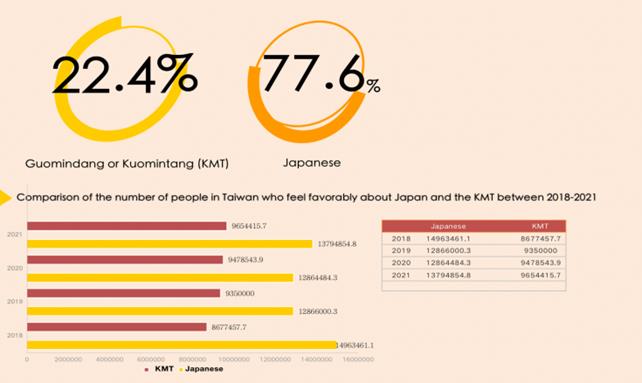

In March 1946, the American newspaper Washington Daily News criticized the Kuomintang’s rule over Taiwan with the front-page headline “Chinese exploit Formosa worse than Japs did”. The use of coercion during KMT rule... ...1895” Citation: Tan Shenge, edited by Qunzui, Reassessing the [9]. At the beginning of 1947, a bloody case caused the huge grievances that had accumulated for more than a year to dissatisfaction with the Nationalist Government and caused the people to live in poverty, forming a general outbreak, and military-civilian conflicts broke out in various places, known in history as the “228 Incident.” Chen Yi, the chief executive of Taiwan Province, ostensibly told Taiwanese that democratic reforms were imminent, but privately asked the central government for reinforcements to suppress them on the grounds that Taiwanese “organized insurgency” and “traitors must be eliminated by force.” A few weeks later, Nationalist reinforcements arrived in Taiwan to begin suppressing the unrest by landing at the ports of Keelung and Kaohsiung, followed by the clean-up operation, in which many Taiwanese elites and civilians were implicated and brutally killed, or imprisoned, executed, or disappeared without trial after being arrested. Wang Sixiang, a journalist from Chinese mainland, reported in “Taiwan’s February Revolution”: “With the public massacre and the terrorist means of covering up the ears and bells.... once arrested, they are often executed without questioning.” Every night, several trucks full of corpses travel between Taipei-Tamsui or Keelung. By the end of March, I had been waiting for a ship in Keelung for 10 days, and almost every day I could see corpses floating ashore from the sea, some of which were sitting and crying around by relatives, and some of which were unrecognized and left to rot. Military police, police, secret services, and provincials who consider themselves conquerors can arrest Taiwanese anytime, anywhere, openly kidnap, and even arrest people at will in the office. Later, the report on the 228 riot incident compiled and printed by the Office of the Chief Executive of Taiwan Province attributed the cause to “the legacy of Japan’s enslaved education.” Wang Baiyuan commented and questioned: “China has been enslaved by the Manchus for 300 years, and women are still wearing cheongsam, why can the Han people be in power after the fall of the Manchus?” This event opened the curtain on the political repression of the White Terror in the 1950s [1, 10]. After that, Taiwan experienced the “White Terror” - a series of harsh measures taken by the Kuomintang during its rule over mainland China to combat and eliminate the forces of the Chinese Kuomintang - which made many of them disillusioned and disgusted with the “motherland” they had originally adored, leading to widespread public discontent in Taiwan. This has caused many of them to become disillusioned and disgusted with the “motherland” that they originally adored, leading to widespread public discontent in Taiwan, and everyone is nostalgic for the years of Japanese rule. So much so that in the statistics of Taiwanese people’s favorability towards Japan and the KMT, without exception, the Japanese “motherland” has won from 2018 to the present. As can be seen from the chart below, Taiwan’s attitude towards its own ‘aggressor’ also shows an interesting reaction. Since 2018, many scholars have been studying Taiwan’s favoritism towards its “motherland” Japan and its “motherland” China. “The Chinese Nationalist Party’s favorability to do the corresponding national favorability survey, in 2023, Singapore’s” United Morning Post “reported that Taiwan’s favorability to Japan has reached a staggering 77.6% This is a thought-provoking data, side by side to verify our theoretical point of view, that is, different levels of identity For example, I have met foreigners and identified myself as a Chinese, while I have compared the two “invaders”, even though Taiwan, as a Chinese, has suffered from the inhuman abuse of its own mother “motherland”. After comparing the two “invaders”, even though Taiwan, as a Chinese, had suffered the inhuman abuse of its own mother “motherland”, would put the “motherland” on an equal footing with the “invaders” and compare them, and then give up its nationalism, and then, after comparing the “invaders” on an equal footing, it would have a new feeling of being a Chinese. Then, after comparing the “aggressor” on the same footing, a new self-concept of the group is created and solidified. As shown in the Figure 1 below, Taiwan’s attitude towards two different types of “invaders” has presented an interesting phenomenon.

Figure 1: Comparison of Taiwan people’s favorability towards Japan and KMT.

Source: Singapore’s Lianhe Zaobao website reported on July 25, 2023

Since 2018, many scholars have investigated the favorability of Taiwan’s population towards the “invaders” Japan and the Kuomintang, the former “homeland” of Taiwan. According to the latest statistics from the Singapore United Morning News in 2023, Taiwan’s favorability towards Japan has reached an astonishing 77.6%. This is a thought-provoking data point that indirectly confirms our theoretical point of view. To elaborate, when people interact with different people, different levels of identity are triggered. For example, when Taiwan encounters foreigners (Japanese), and then positions itself as Chinese, Taiwan’s own group concept is triggered. After Taiwan has the concept of “Chinese”, it has suffered inhumane abuse from its own biological mother - the Kuomintang. It compares its perceived “homeland” and “invader” (Japan) on an equal footing and abandons nationalism. Through the comparison of these two equal status “invaders”, Taiwan has gained a new understanding of its group concept and has been strengthened.

3.Conclusions

The Japanese colonial period and the post-war period in Taiwan both emerged from the invasion of Taiwan as a colony. They both sought or attempted to assimilate or annex Taiwan. Although they were not neighboring countries in geographical or geopolitical terms, these facts form the basis of the comparison. The differences between the two are examined. Firstly, in terms of assimilation policies, the Japanese colonial period was a case of pursuing “identity” through “spiritual” assimilation policies, while the post-war period in Taiwan was a typical example of a single culture. Secondly, there is a significant difference in the intensity of the Taiwanese national sentiment towards Japan and the Kuomintang in terms of resistance and national identity. Due to its relatively long history, nationalist sentiment is strongest in Taiwan. Although resistance in Taiwan is quite strong as a popular sentiment, it is still in its infancy as an organized movement, and its ideology remains weak. Therefore, there is not much nationalist consciousness, only a preliminary sense of group identity. After 50 years of assimilation policies by Japan, the brutal rule of the Kuomintang shattered the so-called sense of group identity. The Taiwanese people’s ideology became relatively mature, with a new understanding and perception of their group identity. In recent years, the definition of Taiwan’s self-group identity has become a fiercely debated issue in local society. Additionally, the political issue of “Taiwan independence” has emerged in recent years. China, the United States, Japan, and Taiwan (China) have begun (or have already begun) to discuss what will happen or is happening when it comes to “Taiwan independence”.

References

[1]. Dogs to Pigs: Declassifying U.S. Intelligence Files on the Eve of February 28, by Nancy Hsu Fleming, translated by Tsai Ding-gui, Taipei: Avant-Garde Publishing House, 2009.

[2]. Tkacik, John J., Jr. (2005). Reassessing the “One China” Policy: Challenges to the One-China Policy in U.S. Academia and Politics. Bootorabi, F., Haapasalo, J., Smith, E., Haapasalo, H. and Parkkila, S. (2011) Carbonic Anhydrase VII-A Potential Prognostic Marker in Gliomas. Health, 3, 6-12.

[3]. Wu, & Rwei-Ren. (2016). The lilliputian dreams: preliminary observations of nationalism in okinawa, taiwan and hong kong. Nations & Nationalism.

[4]. Chang, Yen-Hsien, 1994, Fifty years of political blood and tears, and Chou, Wan-Mei, 1996, Imperialization movements in Taiwan and Korea from a comparative viewpoint (1937-1945).

[5]. Lan, Hongyue (2015). ‘Meiji Knowledge’ and the Politics of Colonial Taiwan: ‘Nationality’ Discourse and Assimilation Policies before the 1920s.

[6]. The transformative course of civic education in Taiwan: changes and challenges in the post-war period (1945-1949) p. 53, Mei-Ying Tang, Taiwan Journal of Human Rights Volume 3, Issue 4, 2016-12.

[7]. Ethnic Groups and the Nation: The Formation of Hakka Identity in the Six Piles (1683-1973) (page archive backup in the Internet Archive), p. 256, Li-Hua Chen, Publication Center, National Taiwan University, 2015-11-02.

[8]. Yang, Bi-Chuan. (1996). Biography of Shinpei Goto. Hitotsubashi Press. p. 62.

[9]. Chen, Senji. (2015). A Review of American Academic Views on U.S. Taiwan Policy. International Political Studies, Vol. 38(2), 142-148.

[10]. Lai, Zehan. Research Report on the February 28th Incident. Taipei, Taiwan: Times Culture. 1994-02-20. isbn 978-9571309064.

Cite this article

Wang,Y. (2023). An Analysis of the Formation and Solidification of Group Concepts in Taiwan During the Japanese Rule and Postwar Periods. Communications in Humanities Research,16,229-234.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the International Conference on Global Politics and Socio-Humanities

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Dogs to Pigs: Declassifying U.S. Intelligence Files on the Eve of February 28, by Nancy Hsu Fleming, translated by Tsai Ding-gui, Taipei: Avant-Garde Publishing House, 2009.

[2]. Tkacik, John J., Jr. (2005). Reassessing the “One China” Policy: Challenges to the One-China Policy in U.S. Academia and Politics. Bootorabi, F., Haapasalo, J., Smith, E., Haapasalo, H. and Parkkila, S. (2011) Carbonic Anhydrase VII-A Potential Prognostic Marker in Gliomas. Health, 3, 6-12.

[3]. Wu, & Rwei-Ren. (2016). The lilliputian dreams: preliminary observations of nationalism in okinawa, taiwan and hong kong. Nations & Nationalism.

[4]. Chang, Yen-Hsien, 1994, Fifty years of political blood and tears, and Chou, Wan-Mei, 1996, Imperialization movements in Taiwan and Korea from a comparative viewpoint (1937-1945).

[5]. Lan, Hongyue (2015). ‘Meiji Knowledge’ and the Politics of Colonial Taiwan: ‘Nationality’ Discourse and Assimilation Policies before the 1920s.

[6]. The transformative course of civic education in Taiwan: changes and challenges in the post-war period (1945-1949) p. 53, Mei-Ying Tang, Taiwan Journal of Human Rights Volume 3, Issue 4, 2016-12.

[7]. Ethnic Groups and the Nation: The Formation of Hakka Identity in the Six Piles (1683-1973) (page archive backup in the Internet Archive), p. 256, Li-Hua Chen, Publication Center, National Taiwan University, 2015-11-02.

[8]. Yang, Bi-Chuan. (1996). Biography of Shinpei Goto. Hitotsubashi Press. p. 62.

[9]. Chen, Senji. (2015). A Review of American Academic Views on U.S. Taiwan Policy. International Political Studies, Vol. 38(2), 142-148.

[10]. Lai, Zehan. Research Report on the February 28th Incident. Taipei, Taiwan: Times Culture. 1994-02-20. isbn 978-9571309064.