1.Introduction

Nowadays, a common phenomenon which is well worthy to be concerned is that the gender differences between male and female is disappearing.

It is commonly agreed that “gender” and “sex” can be distinguished in this way: Gender refers to the sociality, while sex has a biological meaning. The concept of gender is proposed by Gayle Rubin in 1975. It mainly refers to the identification towards gender from its’ family members, friends, social institutions and legal organs. It is one of the social attributes of biology, and is mainly embodied in the gender role and is a cultural composition, which varies not only from time to time but also from ethnic regions. It is a specific social composition. Besides, it is mainly reflected in gender roles, it is also a cultural conception which varies by time and location.

The narrowing of gender difference is reflected in many aspects of life, for example, it can be easily found that the design of clothing is changing, a growing number of clothes are designed for both gender, and the “gender-neu0tral” clothes are becoming popular.

This essay will focus on analyzing two adaptations of The Tempest, [1] which are directed by George Schaefer in 1960 [2] and Julie Taymor in 2010, [3] aiming to figure out the transformation on gender concept by making a comparison between the two selected films.

Nowadays, Shakespeare’s text is required readings for university drama students, and Shakespeare’s plays are adapted by many contemporary theatre companies and film directors (e.g. The National British Theatre and the British Lost Dog theatre company). There are plenty of films and plays which adapted from Shakespeare’s text, making the cultural market more dynamic.

It is a fact that written literature and film are closely connected. Many film directors and producers (e.g. Peter Brook) assume that those written works which are already familiar to the audience have a better chance to be popular when they are adapted into films. So, written works of famous writers are more popular than others. Shakespeare, as the most famous playwright during the Renaissance period is an example. All of his scripts are adapted. In the Guinness Book of Records in 1999, there are more than 400 films adapted from Shakespeare’s work, and this number is still increasing. So, it is an undeniable fact that Shakespeare is the most popular playwright for film directors.

The history of Shakespeare’s adaptation is nearly as long as film studies. The first film came into the world in 1895 and the first film adaptation of Shakespeare came out in 1899. In another word, the history of Shakespeare’s adaptation is almost as long as the history of film. From 1899, there are over 600 films adapted from Shakespeare’s work. Brown believes that Shakespeare’s work are film scripts more than drama scripts. [4] They are the film scripts which appeared 300 years earlier than film itself. His view is reasonable considering the style of Shakespeare’s scripts. It is a fact that the scenes and locations change quickly in most Shakespeare’s scripts. For example, in Antony and Cleopatra, the scenes change for over 40 times which cover Rome, Athens and Syria etc. In this case, the limitation of stage is obvious, but films can reproduce the change of scenes (mainly refers to time and location) in a more technical way.

2.Literature Review

2.1.Adaptation Studies

This research will be built upon adaptation studies. Adaptation studies is inseparable from film studies. The first film came about in 1895, and the first film adaptation that appeared in 1899 is an adaptation of a Shakespearean text, King John.

In the early stage of adaptation studies, film practitioner Balázs proposes three ways of adapting from novels to films. The first way is reproducing written work directly to screen, which retains the integrity of the written work to the greatest extent. The second way is allowing recreation on details on the condition of respecting the original characters and plots. The third way of adaptation allows more freedom, which involves drawing inspiration from the written work and possibility of re-creating characters and plots. [5]

Leitch mentions the view of Eisenstein towards film. Eisenstein proposed that film is the “logical successor” of novel in his essay Dickens, Griffith, and the Film Today in 1944, which illustrates the relation between films and novels. [6] Astruc, on the other hand, in The Birth of a New Avant-Garde: La Camera-Stylo, believes that filmmakers are just like novelists. [7] The only difference is that filmmakers create with cameras while novelists create with pens. Even though Eisenstein and Astruc hold different opinions, their discussions and those of their contemporaries during this period mainly focus on relation between novels and films, and there is nothing specific about adaptation being mentioned.

The next period, which is named “Adaptation Studies 1.0”, is different from the previous one as “general principles of adaptation” proposed by Bluestone, [8] highlighting the primary differences between prose, novels and films. The greatest progress in this period, is the scope being discussed is beyond novels and films. Adaptation is being considered as a wider phenomenon.

Later in 1999, Bluestone’s view was developed by Cartmell and Whelehan in Adaptation: From Text to Screen, Screen to Text. [9] It is from then on that adaptation is gradually discussed as an independent phenomenon. More recently, after the onset of the 21th century, adaptation studies is becoming a field of its own in academic community. Alongside academic journals such as Adaptation, A Theory of Adaptation (2006) written by Hutcheon can be regarded as a milestone of adaptation studies. Hutcheon further expands the scope of adaptation studies and proposes that the adaptation studies should not only exist between literature and film. [10] Her discussion opens up a new layer, allowing adaptation studies to extend beyond film adaptations.

Working with different interpretations of adaptation from previous scholars, Chong Zhang summarizes adaptation studies into “narrow sense” adaptation and “broad sense” adaptation. [11] “Narrow sense” mainly refers to adaptations from written work to screen, while “broad sense” can refer to adaptations between any two different artistic forms. Adaptation studies is an interdisciplinary research field, which includes, but is not limited to, film studies, literature studies and comparative studies. As mentioned, adaptation studies only refers to adaptation from novels to films in early 20th century. However, the scope of adaptation is expanded in the following decades, which means that adaptation studies carries more meanings in different layers. Zhang’s definition of the “narrow sense” basically redefines what is adaptation studies at the beginning of the 20th century, while “broad sense” covers the process of how the scope of adaptation studies is expanded in the following decades. In other words, Zhang’s definition simply dichotomizes the development of adaptation studies in the past 100 years.

Shakespeare adaptation is a considerable part of adaptation studies. Hiroshi Seto’s delineation in Shakespeare in China which is published in 2017 helps us understand Shakespearean adaptations in China in terms of time periods. [12] From 1900 till now, based on political and economic situations, Shakespearean adaptations in China can be understood in six periods. The first period is 1900-1919. In this period, what was introduced are summarized tales of Shakespearean plays in publications such as《海外奇譚》 (haiwaiqitan, Fantastic Stories from Abroad), which was the first Chinese version of Tales from Shakespeare compiled by Charles and Lamb. The second period is 1920-1949. In this period, performances adapted from Shakespearean works increased because translations of Shakespearean texts by Shenghao Zhu and Shiqiu Liang were used in all the performances of the National Drama Academy. These performances showcase a complete set of Shakespearean plays at an early age, which set audiences for the future development of Shakespeare in China.

The third period is 1949-1966. The year 1949 is special as the People’s Republic of China was founded in this year. In the first seventeen years after the founding of new China, ideological propaganda is vital, accordingly, themes of productions and discussions in this period are mainly about Anti-Japanese War, in order to stimulate patriotic enthusiasm of the masses. Only seven stage performances and films were produced in this period and 130 essays on Shakespearean studies were published. Though the number of published essays in this period increased compared with the period of Republic of China (1912-1949), most discussions in these essays are limited by the political factors, which resulted in a phenomenon that most criticism are conducted from a similar perspective and is difficult for unique opinions to be proposed.

The fourth period is 1966-976, which is totally devoid of Shakespearean adaptations in China because of the Cultural Revolution. Even reading Shakespeare is regarded as a behavior that would be heavily criticized and even chastised.

The fifth period is 1978-1990. In the 1980s, the number of performances of Shakespearean plays increased sharply; for example, in 1980, Macbeth was made by the Central Academy of Drama, Romeo and Juliet was made by the Shanghai Theatre Academy. The Merchant of Venice, which is premiered in 1980 in China Youth Art Theatre, is staged more than 200 times within 5 years.

This particular production became the most representative Shakespearean performance of Shakespeare after the Cultural Revolution, which provides references for later Chinese adaptations of Shakespearean works. This production removes some ancient Greek and Roman mythological allusions which might create barrier of understanding for Chinese audiences. Racial and ethnic elements have also been weakened, for example, Shylock's Jewish identity is not mentioned. In another word, this production basically avoids adapting elements which could cause controversy or difficulty of understanding and only keeps the main plot and comic elements. Whether or not these treatments are mature or effective is still worth to be discussed, but popularity of this production has established an audience base for later performances.

Finally, from the 90s onwards, with the development of reform and opening up, a more diverse social background brought forward a freer creative environment. Shakespearean adaptations became more diversified accordingly, which generated a rich and diverse drama market in the 1990s, for example, 《速寫麥克白》 (suxiemaikebai, Sketch Macbeth) was made by Zhejiang University of Media and Communications in 2015.

2.2.Gender Studies

Gender studies will be applied when comparing the differences between the two films. Gender studies is an interdisciplinary subject which covers psychology, sociology, culture studies, anthropology and history etc. There are some significant scholars, such as Pilcher and Whelehan, they collaborating on a book in 2004 called 50 Key Concepts in Gender Studies. [13] This book offers 1500 words expositions of 50 topics central to this field, introduces what is gender studies and how it originated. The topics are authoritative and the 50 entries reflect the complex, multi-faced nature of the field in an accessible dictionary format.

In the same year, Handbook of Gender and Women’s Studies written by Davis Kathy, Evans Mary and Lorber Judith was published. [14] This book is a useful introduction to gender theory and exciting starting-point fresh debates. It presents a comprehensive and engaging review of the most recent developments within the field, including the study of masculinity, the feminist implications of postmodernism, the `cultural turn' and globalization. The authors review current research and offer critical analyses of women's and gender studies in work, the welfare state, family, education, religion, violence and war and feminist global politics.

Twelve years later in 2016, Everyday Women’s and Gender Studies: Introductory Concepts was published, [15] this book is different from the other two as it highlights “the everyday”, the author Ann Braithwaite and Catherine M. Orr introduce a new way to approach an introductory course on women’s and gender studies which is important for students to understand taken-for granted circumstances of their daily lives. This book includes up to five short recently published readings that illuminate an aspect of that concept. Everyday Women’s and Gender Studies explores the idea that “People are different, and the world is not fair” and engages the students in the inevitably complicated follow-up questions which is “Now that we know, how we live?”

Another book which is worth to be mentioned is Threshold Concepts in Women’s and Gender Studies written by Launius and Hassel. [16] This book was published in 2018 which introduced to Women’s and gender courses with the intent of providing both skills-and concept-based foundation in the field. The text is driven by a single key question:” What are the ways of thinking, seeing and knowing that characterize Women’s and Gender Studies and are valued by its practitioners?” Rather than taking a topical approach, Threshold Concepts develops the key concepts and ways of thinking that students need in order to develop a deep understanding and to approach material like feminist scholars so, across disciplines. This book illustrates four of the most critical concepts in Women’s and Gender Studies-the social construction of gender, privilege and oppression, intersectionality, and feminist praxis-and grounds these concepts in multiple illustrations.

3.Case Study: The Tempest

After 1960s, the film adaptations of Shakespeare became more diverse. Films are no longer just another representation of the stage, directors started to add their own understanding into the film when they recreate Shakespeare’s work. With the collapse of the traditional gender concepts, the characterizations of the same character in different films from different period have significant differences.

The following will take two adaptations of The Tempest as an example, analyzing the gender differences between the two films.

3.1.From Prospero to Prospera

The Tempest is a story about the Duke of Milan. Prospero, the Duke of Milan is obsessed with studying magic, his younger brother Antonio is ambitious, under the help of the king of Naples Alonzo. Antonio usurps the throne. As a result, Prospero and his young daughter Miranda are exiled on the desert island. With the help of magic, they conquer the elves and the only inhabitant on the island, which is an ugly aboriginal Caliban. Twelve years later, Antonio, the king of Naples, and his son Ferdinand pass by the island by ships. Prospero finally has the chance to revenge on them. He uses his magic to raise the storm and overturn their ships. They are survived but separated with each other. Ferdinand meets Miranda and falls in love with her. In the end, Prospero forgives them and marries his daughter Miranda to Ferdinand.

The first film adaptation of The Tempest called Forbidden City which came out in 1956. However, this film will not be analyzed in this essay as it is a science fiction, and does not relevant to gender adaptation. The second film is directed by George Louis Schaefer in 1960 and the last one came out in 2010 directed by Julie Taymor. These two films have the same plot and the same characters. However, there are some apparent differences on gender identity of some specific characters. The following will compare these two films from four different perspectives.

Compared with the film in 1960, the most significant change on gender is that the main character Prospero became Prospera in the film in 2010. In another word, this character become a woman, who is the mother of Miranda in this film. Correspondingly, the text changed in the film in 2010 while the film in 1960 completely followed the text. For example, in the film in 1960, when Prospero tells Miranda the reason they have been living in the island, he says:

“My brother and thy uncle, called Antonio—I pray thee mark me, that a brother should/ Be so perfidious! – he, whom next thyself/ Of all the world I loved, and to him put/ The manage of my state, as at that time/ Through all the signories it was the first/ And Prospero the prime duck, being so reputed/ In dignity, and for the liberal arts/ Without a parallel, those being all my study/ The government I cast upon my brother/ And to my state grew stranger, being transported/ And rapt in secret studies.” (1.2.66-77)

This part can be interpreted in this way: When Prospero tells his daughter about the usurpation of his power, he mainly focusing on telling her how his brother Antonio’s ambition is growing while he is concentrating on magic studies. Relatively, in the adaptation in 2010, with Prospero becomes Prosepra, Antonio becomes her husband’s younger brother, the same part is adapted in this way:

“Only your cry will let me give up my own things. After your father died, all the power was passed to me, which stirred up the ambition of his brother, who is also your uncle Antonio. He betrayed us. He is not satisfied with power is controlled by a woman. So, at one midnight, you and me were hurried out of the city on that night.”

In this context, after hurried out by Antonio, Prospera lives on the island for years and becomes the master. From Prospero to Prosepra, the gender transition is designed on the protagonist, who is also the most powerful character in the play, which, could be understood that the controller of power has transferred from male to female. This is a breakthrough of traditional gender concept. In traditional gender concepts, male is a symbol of power, but in recent period, this traditional gender concepts have been impacted and disintegrated again and again. There is a gap of fifty years between these two films, during this period, there are many gender movements which is breaking down traditional gender concepts. For example, in 1997, the UN Economic and Social Council established the importance of gender analysis in decision-making, and defined "mainstreaming gender equality" as gender mainstreaming is a process that addresses any planned action at any level in any field, including analysis of the impact of legislation, policies, or project plans on women and men. It is a strategy that addresses the concerns and experiences of women and men as a means of designing, implementing, tracking, evaluating policies and an integral part of the project plan is considered so that women and men can benefit equally, and gender inequality will not continue, its’ ultimate goal is to achieve gender equality.

However, there is “double identity” of Prospera, she is not only a duke, but also a mother. The reason that Antonio wants the power is that he does not want power controlled by a woman.

The director adapts the text from a female perspective, which reflects the difficulties and struggles of a woman who is trying to be successful in her career and be a mother at the same time. Meanwhile, Antonio’s sexually discrimination is revealed to emphasis on the formidable position of a woman with double identity.

Prospera is a new female image who is suffering from both self-repression and the outside world, which, is also a general struggle of women in the recent times. The director herself wants to reflect the gender status through such adaptation. The patriarchal still suppresses women, and it is difficult for women to perform well both in family and career. In this production, the help of the super-natural power given to her by Ariel, actually could be understood as the helplessness of women in real society under the director's adaptation.

In one word, the director adapts the text to express that even if the status of female has changed, but they still struggle between different identities.

3.2.Different Appearances on Miranda and Ferdinand

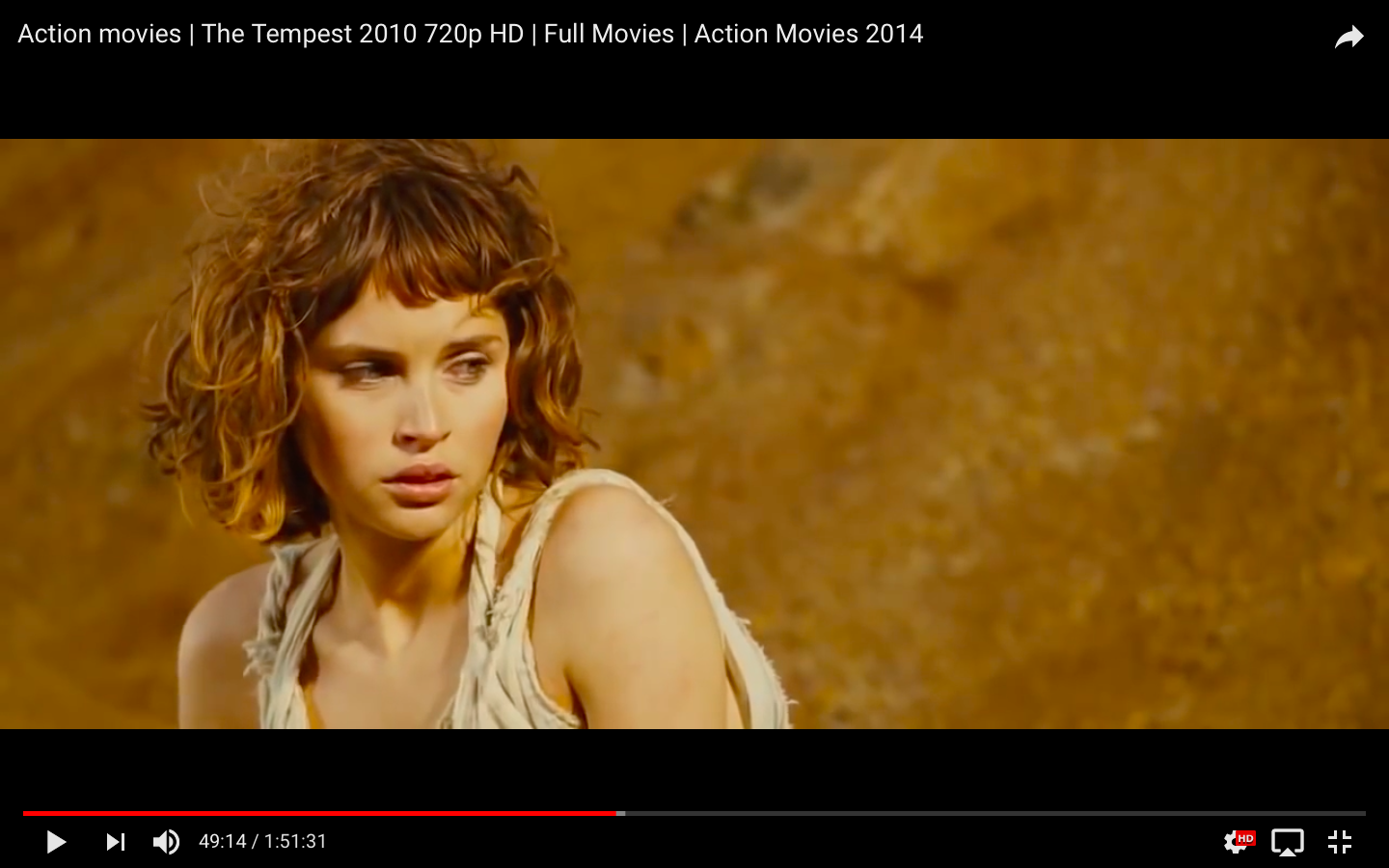

The following will compare the differences of the characters’ appearances between the two films. The four pictures (Figure 1 to Figure 4) display the differences on the appearances of Ferdinand and Miranda. It is rather obvious that in 1960, Miranda has a traditional female image, the long hair and the decent long dress make her looks elegant. (Figure 1) As a contrast, the image of Miranda changed in 2010. The most obvious difference is that she is wearing short hair. (Figure 2) Moreover, both of these two Miranda are wearing white, which is a symbol of purity. As the only female character in the text, Miranda representing romance and innocence, so both directors make this role wearing a white dress shows the similar understanding of the character from the text. However, it is not difficult to find out the two directors add their own understanding of the role by giving Miranda different appearances.

The white dress of Miranda in 1960 is tight, which makes her look decent and elegant, emphasizing her female body shape. Oppositely, the white dress of Miranda in 2010 looks casual and loose which covers her female shape.

|

|

|

|

Figure 1: (7:13) Miranda in1960 |

Figure 2: (27:46) Miranda (right) in 2010 |

|

|

|

|

Figure 3: (18:26) Ferdinand in 1960 |

Figure 4: (28:43) Ferdinand in 2010 |

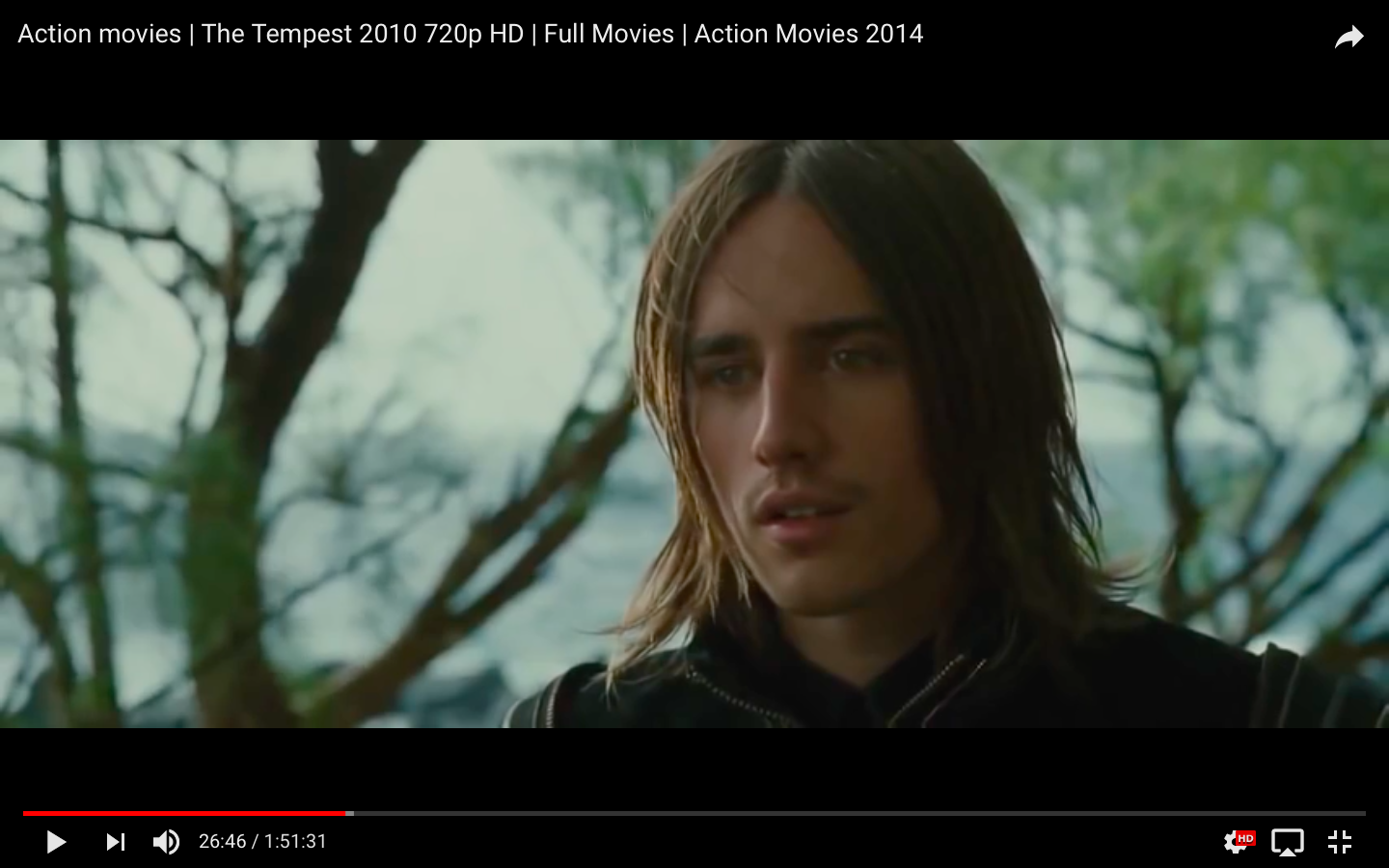

Another character who has two different appearances in two films is Ferdinand. The image of Ferdinand in 1960 is a warrior (Figure 3). He has short hair with a sword at his waist. The style of his clothing is not an ordinary cloth that people would wear in daily life, but it highlights his masculine features, such as the strong thighs and arms. Moreover, the costume also gives him some masculine features, his shoulders look stronger in this costume.

By contrast, in 2010, Ferdinand changes from short hair to long hair, which could be regarded as is an obvious sign of feminization. In addition, he is wearing tight black suits (Figure 4), which covers up his masculine feature. These differences of the same character in two films from different period reflects the impact of new gender concept on art creations.

Butler believes that the most effective way to get rid of the patriarchal is to break the gender boundary of men and women's clothing. [17] In this case, the gender identity is variable. Because once the gender boundary of clothing is broken, people will gradually liberate from a certain gender identity. From this point of view, it is obvious that clothing is considerable in gender roles. From the transitions in the appearance of Ferdinand, it is not hard to see that the gender boundary between men and women is disappearing.

3.3.Different “Connection” between Miranda and Ferdinand

Besides, from the perspective of mise-en-scène, the relationship between Miranda and Ferdinand is clearly displayed. The following eight pictures are from the film in 1960.

|

|

|

|

Figure 5: (20:07) Miranda looking at Ferdinand (1960) |

Figure 6: (20:15) Ferdinand looking at Miranda (1960) |

The first two pictures (Figure 5, Figure 6) are when Miranda and Ferdinand first meet each other. It can be seen that both of the two pictures are close shots. However, Miranda is slightly looking up at Ferdinand while Ferdinand is slightly looking down at Miranda. In the text, Miranda is the daughter of the most powerful person Prospero in the island, whereas Ferdinand is just passing there by accident. In this case, Miranda should have a higher position than Ferdinand in this island, but these shots visualizing a traditional gender relation, giving audience an imply that as a female character, Miranda is relying on Ferdinand. The gender concept of the director can be seen from these two shots.

The same eye-line matching in different shots can also be found in the film.

|

|

|

|

Figure 7: (20:32) Miranda and Ferdinand (1960) |

Figure 8: (22:30) Miranda and Ferdinand (1960) |

|

|

|

|

Figure 9: (40:16) Miranda and Ferdinand |

Figure 10: (40:45) Miranda and Ferdinand |

|

|

|

|

Figure 11: (40:54) Miranda and Ferdinand (1960) |

Figure 12: (41:05) Miranda and Ferdinand (1960) |

These six pictures (Figure 7 to Figure 12) include medium shot, full shot and close shot. The common point of these shots is that the female character is always looking up at the male character. Beauvoir (1949) points out that women are socially constructed as others, and women's disadvantages are not formed naturally. [18] This hierarchy is a result of patriarchy and it serves to consolidate male power. Therefore, women are regarded as a product of male power, they have a lower social status than male. Her point of view can be justified in the film of 1960. However, in the film of 2010, the relationship between the same characters has clearly changed from more than one perspective. The following will analyze the transformation in the film in 2010 through the same aspects.

Figure 13 & 14 are also when Miranda first meets Ferdinand. A considerable change is that the eye-line between the two characters is horizontal. The female character is no longer looking up at the male character. Instead of giving the audiences a feeling of “relying”, this director is trying to establish an equality between male and female. Besides, figure 13 & 14 are reverse-shots, both Miranda and Ferdinand are in the middle of the screen, taking up almost the same space, which also reflects an equal relationship between them. And it is also engaging to see that at some point, the female character is looking down at the male character, while the male character is looking up at the female character (Figure 15 & 16).

|

|

|

|

Figure 13: (26:43) Miranda looking at Ferdinand (2010) |

Figure 14: (26:46) Ferdinand looking at Miranda (2010) |

|

|

|

|

Figure 15: (48:35) Miranda and Ferdinand (2010) |

Figure 16: (49:14) Miranda looking at Ferdinand (2010) |

4.Conclusion

This research is interdisciplinary, which covers film studies, gender studies and adaptation studies. As a result, it is challenging because interdisciplinary researchers need to apply knowledges from different disciplines at the same time, and recognize the connection among them, while use theoretical knowledge to conduct the research.

Shakespeare, as one of the most famous playwright in the world, whose work have already been adapted and studied by a considerable number of directors and scholars. As a result, it is also challenging to build a unique view among the others, which requires researchers have a critical academic thinking, and be able to point out the gap which is worthy to study.

Compared with Shakespeare's four tragedies and four comedies, The Tempest is creation which is less discussed. However, this play has many considerable uniqueness. It is the last work of Shakespeare, and it is also the only play with only one female character (Miranda) in it. This essay takes two films adapted from The Tempest in 1960 and 2010 as case studies, approaching gender transition of female and male characters through applying gender studies, hoping to provide a new perspective for future researchers.

References

[1]. Shakespeare, W., Clark, W. G., & Wright, W. A. (2009). The Cambridge Shakespeare: THE TEMPEST.

[2]. Schaefer, G. (Director). (1960). The Tempest [Film]. Mumbai Mantra Media.

[3]. Taymor, J. (Director). (2010). The Tempest [Film]. Chartoff Productions.

[4]. Brown, D. (2000). Film and theory: An anthology. Reference Reviews, 14(7), 36-36.

[5]. Balázs, B. (2011). Béla balázs: Early film theory. Visible Man & the Spirit of Film.

[6]. Leitch, T. (Ed.) The Oxford handbook of adaptation studies. New York: Oxford University Press, 2017, 784 p.

[7]. Astruc, A. (1968). The birth of a new avant-barde: La camera-stylo.

[8]. Bluestone, G. (1961). Adaptation or evasion: \"Elmer gantry\". Film Quarterly, 14(3), 15-19

[9]. Cartmell, D. & Whelehan. I. (1999) Adaptations: From text to screen, screen to text. Routledge.

[10]. Hutcheon, L. (2006). A theory of adaptation. Routledge.

[11]. Zhang, C. (2009). Adaptation studies and adaptation research. Foreign Literature Review (3), 12.

[12]. Hiroshi, S. (2017). Shakespeare in China: A history of Chinese reception of Shakespeare. Guangdong People's Publishing House.

[13]. Borden, I., Penner, B., Rendell, J., & Pilcher, J. (2004). 50 key concepts in gender studies. Routledge.

[14]. Davis, K. E., Evans, M. S., & Lorber, J. (2004). Handbook for gender and women's studies. Language.

[15]. Braithwaite, A., & Orr, C. M. (2016). Everyday women's and gender studies: Introductory concepts. Routledge.

[16]. Launius, C., & Hassel, H. (2015). Threshold concepts in women and gender studies: Ways of seeing, thinking, and knowing.

[17]. Butler, J. (1990). Gender trouble.

[18]. Beauvoir, S., & Cheng, C. (2015). The second sex. Shanghai Translation Publishing House.

Cite this article

Kong,X. (2024). Differences Between Two Shakespearean Adaptations: An Analysis of Two Film Adaptations of The Tempest from the Perspective of Gender. Communications in Humanities Research,26,256-266.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Interdisciplinary Humanities and Communication Studies

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Shakespeare, W., Clark, W. G., & Wright, W. A. (2009). The Cambridge Shakespeare: THE TEMPEST.

[2]. Schaefer, G. (Director). (1960). The Tempest [Film]. Mumbai Mantra Media.

[3]. Taymor, J. (Director). (2010). The Tempest [Film]. Chartoff Productions.

[4]. Brown, D. (2000). Film and theory: An anthology. Reference Reviews, 14(7), 36-36.

[5]. Balázs, B. (2011). Béla balázs: Early film theory. Visible Man & the Spirit of Film.

[6]. Leitch, T. (Ed.) The Oxford handbook of adaptation studies. New York: Oxford University Press, 2017, 784 p.

[7]. Astruc, A. (1968). The birth of a new avant-barde: La camera-stylo.

[8]. Bluestone, G. (1961). Adaptation or evasion: \"Elmer gantry\". Film Quarterly, 14(3), 15-19

[9]. Cartmell, D. & Whelehan. I. (1999) Adaptations: From text to screen, screen to text. Routledge.

[10]. Hutcheon, L. (2006). A theory of adaptation. Routledge.

[11]. Zhang, C. (2009). Adaptation studies and adaptation research. Foreign Literature Review (3), 12.

[12]. Hiroshi, S. (2017). Shakespeare in China: A history of Chinese reception of Shakespeare. Guangdong People's Publishing House.

[13]. Borden, I., Penner, B., Rendell, J., & Pilcher, J. (2004). 50 key concepts in gender studies. Routledge.

[14]. Davis, K. E., Evans, M. S., & Lorber, J. (2004). Handbook for gender and women's studies. Language.

[15]. Braithwaite, A., & Orr, C. M. (2016). Everyday women's and gender studies: Introductory concepts. Routledge.

[16]. Launius, C., & Hassel, H. (2015). Threshold concepts in women and gender studies: Ways of seeing, thinking, and knowing.

[17]. Butler, J. (1990). Gender trouble.

[18]. Beauvoir, S., & Cheng, C. (2015). The second sex. Shanghai Translation Publishing House.