1. Introduction

1.1. Research Background

Modern anthropology and spatial politics have consistently advocated for the understanding of the “other,” encouraging self-reflection through the lens of the “other.” Space is a crucial political issue and often the locus of political struggles. The space of the other serves as a fundamental theoretical reference for comprehending the specific relational characteristics between spatial boundaries and the demarcation of space. “‘The other’ not only occupies a specific position in physical space but also invariably corresponds to specific social strata, fitting into certain social structures and mechanisms.” [1] However, this statement also implies that the “other” should not only manifest as a unique spatial type but should, in reality, encompass various characteristics reflecting individuals, groups, interests, sensitivities, etc., exclusive to this relatively distinctive spatial area. [2]

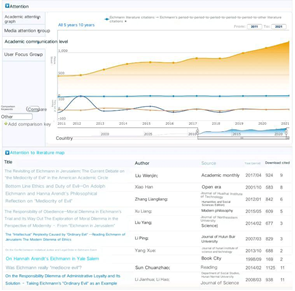

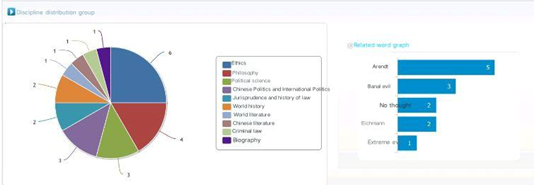

When it comes to political ethics, everything we perceive or almost everything carries some degree of political nature. As an integral part of the social process, political, legal, and ethical considerations are closely linked to other social activities and can be influenced by other social processes. Political ethics primarily examines the ethical aspects of political and legal operations and explores the morality of political controversies. It should never be regarded as metaphysical within an ivory tower. Analyzing the historical context of Eichmann’s era and trial records, many scholars have identified the disappearance of what is known as the “banality of evil,” eroding thought processes and fundamental ethical consciousness. Big data also demonstrates the rapid interdisciplinary development of this issue (as shown in Figure 1 and Figure 2). As the democratization process progresses and international exchanges, cooperation, and technological innovations expand, the scope of exploring the causes and solutions to this issue has broadened. This paper, by examining the political ethical alienation under the perspective of the space of the other, aims to provide readers with a novel viewpoint to scrutinize the political ecological alienation in the space of the other.

Figure 1: “The Other” and “Eichmann” Related Research Heatmap.

Figure 2: “Eichmann” Recent Research Distribution.

1.2. Significance of the Study

From a theoretical perspective, scholars both domestically and abroad have conducted numerous studies on related alienation throughout history. In the current unprecedented era of significant changes and the intertwining of a century’s pandemic, coupled with the escalating development of the technological revolution, paying attention to political ethical alienation is conducive to integrating and even extending relevant theories.

In terms of practical significance, interpreting political ethical alienation under the framework of the space of the other using Adolf Eichmann as an example is beneficial for raising awareness of the deteriorating political ecology in our country. However, to fundamentally change the political ecological environment, it is imperative to effectively overcome the phenomenon of political ethical alienation in reality. Those in power must uphold the moral bottom line of governance, adhere to political ethics, cultivate strong capabilities, and simultaneously insist on confining power within the institutional framework. This creates a comprehensive mechanism of incorruptibility, incapability of corruption, and resilience against corruption, ensuring that power is effectively restrained by mechanisms such as anti-corruption. Ordinary citizens should resist servility, maintain independent thinking, refrain from using new-era online weapons like keyboards for spreading false information and propagating hatred, avoiding becoming an unethical mob. Only through such efforts can the well-being of the nation and its people be truly promoted. Therefore, this study is conducive to advancing the process of socialist modernization and civilization.

1.3. Current State of Foreign Research

A German-speaking interrogation expert, Aharoni, vividly described in his work “Eichmann in Operation: The Facts of Pursuit, Arrest, and Trial” the intricate process of the Israeli Mossad agents capturing Eichmann and the factual records of the trial in Jerusalem. The film “Operation Finale,” produced by MGM, was released in the United States in 2018, vividly reenacting the determined mission of Mossad to reach Argentina, clandestinely investigate, and apprehend Adolf Eichmann, along with the subsequent consequences.

Hannah Arendt contributed to this field with her controversial work “Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil.” The enduring controversy surrounding this book, even after half a century, is noteworthy, especially considering the ethical condemnation from prominent figures and intellectuals among Western Jewish communities. Margaret Canovan believes that Arendt’s political thought process originated from her reflective consideration of the moral barriers in totalitarianism. Stanley Milgram’s research on the concept of “obedience” is closely related to the massacre and Arendt’s work. The results of the experiment further validate the profound nature of Arendt’s thoughts. Witnessing hundreds of ordinary people obeying authority in the electric shock experiment must have been shocking for both readers and the author.

The German independent philosopher, Bettina Stangneth, after analyzing extensive data, found that Eichmann was not a blindly obedient ordinary official but a cunning, unrepentant murderer. This corrects the long-standing public misconception about Eichmann. [3]

Emmanuel Levinas, a French philosophical figure, is renowned for his perspective that “only by turning from oneself to the other, assuming ethical responsibility for the other, can true justice and peace be achieved.” [4] The “other” he explores here should be absolute, thorough, with independent character, occupying a prominent position in the field of ethical research.

1.4. Current State of Domestic Research

Chinese scholars have a relatively late introduction to the discourse on Eichmann, mainly involving the translation of Arendt’s original works, biographies, and the compilation of theoretical criticisms by foreign scholars on Arendt. For instance, Xu Liang, a lecturer at Sun Yat-sen University, mentioned that Arendt’s reflections have significant implications for humanity as a whole. Even in the collective crimes under totalitarianism, individuals should still bear responsibility for their blind obedience. Han Zhenjiang, a professor in the Faculty of Humanities at Dalian University of Technology, pointed out that this trial undoubtedly triggered political and ethical dialogues about evil and moral responsibility. Exploring this topic also has relevance for the younger generation in China studying Japanese aggression history. [5] Sun Tianzi of City University of Hong Kong expressed that the cruel demon imagined by people might just be an ordinary person, and the decline of moral sense arises from the reproduction of social distance. Rebuilding modern morality requires maintaining basic respect and responsibility towards others. [6]

Additionally, concerning the trial report in Jerusalem, many scholars have contemplated whether Mossad’s capture and detention of Eichmann align with justice. Zhang Rulun, a prominent figure in China, first explored the issues of “justice” in Arendt’s view of the Eichmann trial. Professor Xu Ben, a graduate of Fudan University, advocates that judgment is a link between human thought and civic life, representing an ability in the public domain. [7]

Wang Yinli, in her doctoral thesis “Hannah Arendt: Between Philosophy and Politics,” argues that the report on the “banality of evil” serves as a crucial turning point guiding people from the political field back to philosophical ethical considerations of “power and authoritarianism” and “public space.”

1.5. Innovations of This Paper

This paper delves into the political ethical alienation in the space of the Other, using Eichmann as a typical case. The aim is to find a way out of ethical alienation in the process of social development, to raise a more vigilant awareness of the political ecology in China, and to take preventive measures while improving the political environment. Analyzing the issue through a case study provides a more intuitive, typical, and scientific approach. Furthermore, the paper collects and organizes typical cases from websites, analyzing them to conclude that approbatory experiments and ideological indoctrination have a significant impact on human behavior. By dynamically and statically analyzing the logical generation of “political ethical alienation,” the paper aims to propose more applicable solutions to break through the dilemma.

The research employs two methods:

1. Literature Review Method: By browsing websites and consulting database literature, general concepts related to the keywords and relevant theoretical foundations are obtained. In this study, the literature review method is used to provide knowledge sources and theoretical support, integrating current research trends and results in the academic community. It serves as a theoretical guide for the writing of this paper based on existing research.

2. Case Analysis Method: The Eichmann trial and related experiments on human ethics provide important empirical material for the theoretical research in this paper. Collected from websites, typical cases are analyzed to deduce that approval experiments and ideological indoctrination have a significant impact on human behavior. The paper approaches the generation logic of “political-ethical alienation” dynamically and statically to better propose solutions for overcoming the dilemma.

2. Relevant Theories and Concepts

2.1. On the Space of the “Other”

At the present stage, the academic community has yet to provide a clear definition of the “space of the other.” However, in the course of relevant discussions in this paper, various viewpoints and theories from scholars are synthesized.

The concept of the “other” mainly originates from the propositions of Hegel and Sartre: “Referring to an unfamiliar opposing aspect or negation beyond the dominant position, the authority of the subject is defined because of its existence.” [2] Deleuze once proposed: “The ‘other’ is neither subject nor object but appears as a completely different existence—an alternative world, a possibly terrifying alternative world... The so-called ‘other’ is, first and foremost, the existence of a possible world.” [8]

The spatial model of the Middle Ages was initially broken by Galileo, and one of his most significant discoveries was the concept of an infinitely open space. [9] In the latter half of the 20th century, Henri Lefebvre introduced the idea of “spatial production” into critical studies of bourgeois society, subsequently making spatial perspectives increasingly prominent and shifting the focus of theoretical research from time to space.

Michel Foucault, in a lecture on March 14, 1967, titled “The Space of the Other,” attempted to connect and transform the linear relationship of historical narratives with the power relations from the core to the periphery. According to his theory, compared to the core, the peripheral areas represent another form of the “space of the other,” and its emergence is precisely a product of the mechanisms of disciplinary power in modern times. “Discipline is a special technique of power that sees individuals as objects of practice and tools of practice.” [10]

Today, modern anthropology and spatial politics advocate understanding research on the “other.” The “other” we seek and study today holds a place in ethics. Philosopher Emmanuel Levinas believes that true justice and peace can only be embraced by turning from oneself to the “other” and taking ethical responsibility for the “other.” [4] The space of the “other” not only refers to the locations and narrative times where stories take place but also plays a crucial role in representing story times spatially and driving the entire narrative development process. The space of the “other” is also a fundamental theoretical reference for understanding the specific relational characteristics of space boundaries and delineation. [11]

2.2. On Political Ethics

Scholars generally believe that political research encompasses two distinct branches: political science and political philosophy. For most of the 20th century, political theory faced a dilemma. On one hand, influenced by logical positivism, empirical verification overshadowed traditional normative ethics and political analysis studies, causing philosophers to lose interest in morality and issues. On the other hand, political science, influenced by the “behavioral science revolution” of empiricism, abandoned the entire normative political thought tradition and focused on the study of measurable political behavior. Marx’s spatial political critique ethics highlights a triple evolution path of deconstruction, construction, and reconstruction. The process of humanity transitioning to a post-industrial society will be a fusion of ethics and political science.

Political science before World War II often overlooked human elements. Max Weber emphasized the role of political institutions and ideas and proposed the concepts of instrumental rationality and value rationality. In his famous lecture “Politics as a Vocation,” Weber openly stated that politicians must possess the three prerequisites of “endurance, sense of responsibility, and sound judgment.” Political judgments based on subjective and imaginative considerations, as well as the “reference points” of political judgments, must adhere to basic moral positions; otherwise, it may lead to a reduction or expansion in the use of political judgment concepts and politically improper behavior. Therefore, evaluating the ethical value of political trials is essential and necessary to ensure political justice and the smooth conduct of political trials.

As for the emergence of fascism: firstly, a crisis occurred in capitalist society, and the working class gradually radicalized. Sympathy for the working class among the masses grew, and the urban and rural lower-middle class also desired change. At this time, powerful manipulation behind the scenes occurred by the big bourgeoisie attempting to avoid revolution. Subsequently, the fighting capacity of the working class weakened, confusion and indifference grew, and social crises worsened. The lower-middle class felt despair and the desire for change. Collective panic set in; it was willing to believe in miracles and accept extreme means. Its animosity towards the working class, which had disappointed it, deepened. These factors paved the way for the rapid formation and victory of fascist political parties.

2.3. Philosophical Origins of Alienation Theory

Karl Marx stands out as the foremost political and social theorist of the 19th century, leaving a profound mark on posterity with his works on social classes and modern capitalism. Although he did not delve extensively into the nature of politics and the state, his writings largely reflect the dominance of capitalism. Nevertheless, his fundamental and vivid depictions set his work apart, making it more vibrant compared to some other sociologists’ works.

Concerning his theory of alienation, Marx examined real individuals and, rooted in historical materialism, posited that the generation and abandonment of alienation constitute a socio-historical process following a dialectical development. [12] In Marxist theory, “alienation” refers to the process in capitalism where surplus value is disguised as operating profits, labor becomes a commodity, and the laboring masses are reduced to slaves or mere machines for capitalists. [13] Philosophically in Marxism, it denotes the subject reaching a certain stage, splitting into its opposite and becoming an external, alien force. Fascism initially took root as an opposition to Marxism, with its core propaganda being anti-Marxist. Fascists, in a broader sense, opposed all “left-leaning” ideologies, including general liberalism, but their strongest opposition was directed at Marxism.

The theory of alienation first appeared in Hegelian philosophy. Hegel believed that the external manifestation process of ideas develops from inadequate expression to full expression. After developing in humanity, it is manifested as the outcome of human spiritual activity, expressed through ethics, moral norms, and laws. [14]

In the study of Satrean existentialism, scarcity is seen as the root and cause of alienation. Scarcity, according to Sartre, causes alienation, and the only way to overcome alienation is to completely eliminate scarcity. However, Sartre believed that scarcity in human society is universal, eternal, and cannot be eliminated. Therefore, the conclusion is that alienation can never be overcome; it is an eternal state of human existence, an inherent phenomenon in human society. [12]

In conclusion, political-ethical alienation is a peculiar yet prevalent socio-historical phenomenon. Over a millennium ago, the “distinction between reason and desire” was a core theme in Confucian ethical thought, garnering considerable attention from Confucian scholars. However, as ethics became increasingly intertwined with polarized politics and authoritarianism, ethical and moral propositions, inherently rational, became susceptible to transformation into tools for societal control by the ruling class.

2.4. A Brief Discussion on Eichmann

Adolf Eichmann was a mid-ranking official in Nazi Germany during World War II, steadfastly devoted to his “official duties” of deporting Jews and escorting them to slaughterhouses. After escaping Germany, he was arrested in Buenos Aires in 1960 and sent to trial in Jerusalem, where he met his end by hanging. There exists a Jewish political ethicist, who, as a witness to the Jerusalem trial, harbored doubts, confusion, and anger towards Eichmann. However, through the writings of this philosopher—Hannah Arendt—we can discern that, until the eve of the trial, Eichmann still believed he was innocent. He insisted that the puppet master behind the scenes—the Nazi regime—was the one who should bear responsibility, and he himself was just a sacrificial “component” in the grand machinery. In the trial records, the argument over whether Eichmann was a mere cog or the prime mover formed a prolonged stalemate. So, should the responsibility for the millions slaughtered be attributed to the individual (Eichmann himself) or to the collective regime? [15]

Throughout the entire operation of the Holocaust, it must be acknowledged that, not only Eichmann but anyone else in his position, under the backdrop of inhumane orders from the SS, would likely have committed equally cruel acts. “It is widely known that the massacre of extermination camps was, in fact, carried out by Jewish overseers themselves. This fact has been confirmed by witnesses presented by the prosecution—they detailed how gold teeth were extracted and hair cut in gas chambers and boiler rooms, the process of digging mass graves, and subsequently removing and concealing the bodies, erasing traces of the collective slaughter.” [16]

If Eichmann represents not an individual but a group of people, a group unable to break free from their identity fragments, unable to transcend their present selves, we can easily discover that, while Eichmann as an individual did not directly commit murder, as a collective, they killed countless people. To a large extent, this is also the sinister secret of evil politics—it dissects evil into numerous small portions, so small that individual perpetrators cannot fully feel the weight of the evil they commit. They merely perform their duties diligently. However, when these diligent duties converge, a horrific scene emerges. Eichmann undoubtedly felt unjustly treated; he might have been just one in a thousand in the Nazi army, committing a minuscule fraction of evil. In the end, however, he was judged as a hundred percent evildoer, oblivious to the fact that his diligent duties required him to be accountable for the bodies of thousands of Jewish people. Perhaps this is precisely the horrifying aspect of banal evil. We find that the staging of evil does not require many true evildoers; it only needs the orchestrators at the top and countless “slightly myopic” ordinary people who, without thinking, diligently perform their duties, each focused on their immediate desk.

Long ago, the renowned philosopher Jaspers reflected: when injustice unfolds around us, why can’t we resist servility, uphold wisdom, and openly resist? Here, he issues a weighty, soul-searching question through philosophy to everyone. He wants to convey to the public through practical actions that in the face of the vast darkness of nationalism, judging a few blindly following Hitler like Eichmann is clearly not enough, because in that disaster, almost everyone played the role of unjust enablers, signaling approval through silence and blindness to the Nazis.

3. Causes of Moral and Ethical Alienation in the Space of the Other

3.1. Alienated Subject

It is often said that one sees those outside one’s own group as fundamentally different. Viewing individuals from one group as “the Other” has historically been a significant factor in racial massacres or genocides. Taking the United States as an example, when colonizers (the civilized) defined Native Americans as “the Other” (savages), it led to discrimination against Native Americans. The Other may differ significantly in appearance, customs, culture, and way of life. Consequently, the Other cannot integrate, and there may be no genuine desire for their integration. This situation easily gives rise to peculiar imaginations about the Other, leading to fear. Unfounded suspicions are created or manipulated, spreading to evoke greater fear. When this fear reaches a certain level, it evolves into hatred, eventually escalating to violence, even resulting in large-scale ethnic cleansing.

In the perspective of Zygmunt Bauman, “Contemplating the Holocaust should not only occur on the level of modern civilization but, more importantly, on the ethical level. Nazi Germany exterminated over five million Jews, something impossible in pre-modern states.” [5] I believe the more crucial reason is that they, from the top to the bottom of the pyramid, underwent a transformation in mentality, an alienation, against moral condemnation.

In the records of the trial, Eichmann’s “sophistry” with the defense is not entirely baseless. Confiscating Jewish property, deporting Jews, and even exterminating Jews were a series of legal and decision-making processes issued and ordered by the “national machine”—the government. [15] However, it is also hasty to readily accept collective responsibility.

As mentioned earlier, Eichmann alone may have been just one in a thousand in the Nazi army, committing a minuscule fraction of evil. Yet, unbeknownst to him, his diligent duties required him to be accountable for the bodies of thousands of Jewish people. He needed to face the responsibility for thousands of fractions of 0.01 percent. Even from a mathematical perspective alone, the weight of this responsibility cannot be ignored. Therefore, even if he was just an executor, he should bear the responsibility for his thoughtlessness and contribution to the prevailing situation.

As advocated earlier, considering “collectives as the responsible subject” often manifests societal harm by dissolving and overlooking individual responsibility. Zygmunt Bauman believes that the demand for a fine division of labor in modern society results in an uncertain state of “guilt but not a sinner; there are crimes, but no criminals; there are signs of guilt, but no confessor.” [17] Because individuals in this state face alienation, lose their humanity, and moral self has already declined, goodness and responsibility become nothingness. This aligns with Eichmann’s statement during the trial, claiming he was merely mindlessly fulfilling his duties.

3.2. Motivation for Alienation

3.2.1. Violence and Repression

The ritualization and universalization of violence are crucial steps. Throughout history, organized spectacles of various forms of torture are vivid manifestations of ritualized violence. When the Nazis came to power, this escalated violence and repression became evident. Starting in 1933, movements resisting Jews began; in 1936, the Aryanization directly deprived Jews of their property; on November 9, 1938, known as “Kristallnacht” or the “Night of Broken Glass” in history, few know that behind this beautiful and somewhat illusory name is a terrifying campaign against Jews, their homes, and businesses, launched by the German Nazis in Germany and Austria. It laid bare violence, resulting in the killing of hundreds of Jews and the transportation of tens of thousands to concentration camps. Following this, in 1942, the Final Solution was proclaimed, solidifying the course of action.

The term “rational ignorance,” a specialized term in political economics often used in scenarios like voter elections, seems applicable to the German civilians who, in extreme fear, mentally shielded themselves, choosing rational ignorance about things they could not endure or change.

3.2.2. Temptation of Power and Resource Interests

The political fear brought about by totalitarianism taught people silence, while the lure of interests would breed active participants, presenting a significant opportunity for creating a mob. In the trial records of Eichmann, he appears to be recognized merely as an ordinary and mediocre bureaucrat passively following orders. However, the facts reveal that when power spread its bait in society, he actively chose to join the Nazis, continually climbed the ranks of power, ultimately becoming the “czar” of the Jews. Therefore, Eichmann was not a passive, mindless component; he actively pursued the bait, willingly entered the killing machine, and became an executor. It is akin to a drinker who initially chose to approach the drinking table, later excusing himself by claiming that he became drunk due to others’ persuasion. Eichmann’s evil, rather than being mediocre, can be seen as the reluctance to be ordinary when facing the temptation of self-interest during political-ethical alienation.

All mechanisms employed by centralized systems to recruit enforcers aim to monopolize power and resources to the maximum extent, leaving ambitious individuals with only one path to take.

3.2.3. Balancing Costs and Benefits

While we may have judged one Eichmann, countless “rational actors” during the same period weighed the pros and cons. If one were to lay bare their calculations, it would essentially involve a comparison: emotional release, identity affirmation, maintaining a normal or even comfortable life versus potential guilt and the possibility of facing judgment in the years to come. From this perspective, the cost of acquiescence and approval can be considered extremely low.

3.3. Opportunities for Alienation

To turn people into demons, what does a political movement need to do? For the sake of our discussion, let’s start from a perspective that makes sense of this question. Let’s assume that people are not inherently evil beings but require effort to be coerced into committing wicked deeds. This assumption is crucial and contradicts the common belief about wartime behavior: that without social constraints, human brutality will emerge.

3.3.1. Approval Experiments Reveal Ethical Weakness

In reality, often war is not even necessary; only a bit of approval is needed, like a simple white coat, as illustrated by Milgram’s shock experiment or a uniform, as seen in the “Stanford Prison Experiment.” These experiments show that without any apparent reason, we can harm others. It is worth mentioning that the shock experiment delves into human nature, revealing its darker side. While following conscience and maintaining independent thinking may seem simple, the unfortunate reality is that very few can truly break free from the cycle.

3.3.2. Ideological Brainwashing

If interests drive people to pursue actively, fear induces silence, ideology can make individuals fanatic. Various ideologies essentially act as a form of ideological magic and a display filter. They can sanitize evil into so-called good or, at the very least, reduce significant evil to minor transgressions. During World War II, the Nazis avoided identifying themselves as killers; official documents never used the word “kill” but rather referred to it as a “thorough cleaning.” Totalitarian leaders like Hitler propagated biological progressivism through public speeches, instilling ideologies such as loyalty to the ruler and patriotism. In other words, their words and actions consistently asserted that Germany was the best country in the world, ingraining this ideology in the minds of Nazi party members. Looking at it from another perspective, this ideology implies a disdainful attitude towards other races. It means that when a Nazi joined the army, no matter how many Jews they killed, they would not see any difference from killing cats or dogs. Another manifestation is the need to entrust one’s life to the leader; obeying all orders is considered a sacred duty and the highest honor. As one enlists, this ideological brainwashing intensifies, making it increasingly difficult to resist when superiors issue commands.

3.3.3. Collective Induction

Humans have an impulse towards obedience and group conformity, and when exploited, these tendencies can lead to violence. When an individual becomes part of a collective, individual wisdom and qualities are weakened by collective psychology.

Untrained individuals are not harmless, but at least they are not wolves on a leash that would attack once unchained. History has proven that to create a successful killer, training is needed to gradually overcome what Arendt referred to as “animalistic compassion.” In the book “Moral Man and Immoral Society,” Reinhold Niebuhr sharply condemns the “moral dullness of human collectives.” Ordinary people willingly become tools of the group, driven unquestionably by “desire” and “ambition,” eventually providing power to these individuals. Group identity serves as both a protective shell during social unrest and a means of minimizing moral conventions.

Gustave Le Bon indicated that collective unconsciousness is the hidden force behind all social phenomena. In a study of moral risks in group actions—specifically anonymity and aggression—American psychologist and retired Stanford University professor Philip Zimbardo found that any item capable of obscuring individual characteristics, such as loose coats, the darkness of night, face paint, masks, and sunglasses, increases the likelihood of antisocial behavior.

Group membership not only promotes deindividualization (where moral self disappears into the group) but sometimes also fosters what is known as “intra-individuation”—where the moral self is psychologically subdivided. In the state of “intra-individuation,” the self shrinks, stiffens, and segregates into self-sufficient units, becoming narrow, non-communicative, or even conflicting functions. In the state of “deindividualization,” the self no longer has specificity, and in the state of “intra-individuation,” the others no longer have specificity. In other words, in the state of “deindividualization,” your relationship with yourself is regulated through your collective identity, while in the state of “intra-individuation,” your relationship with others is regulated through your specific social role, making others an abstract entity.

The executor of the Nazi Holocaust, Eichmann, is a prime example of “intra-individuation.” Another example is Charles-Henri Sanson, an executioner during the French Revolution. It must be acknowledged that when one becomes an executioner, there is a responsibility to do what needs to be done. A good executioner will kill, a good doctor will ignore pain, and a good lawyer will lie. We often say that the law provides minimal authorization, while personality provides maximum resistance. To create war criminals, demons, and evil spirits, as described by interviewed Japanese veterans, requires the opposite combination: maximum authorization and minimal personality. Under collective induction, both deindividualization and intra-individual differentiation appear so natural and yet inevitably evoke a sense of lamentation.

3.3.4. Exploration of Human Nature

Regarding the issue of political ethical alienation in the space of the other, the content of the “Asch Conformity Experiment” can provide us with some insights. In the experiment, subjects were asked to compare the lengths of some simple lines. Initially, each subject accurately distinguished the lengths of the lines in front of them without difficulty. However, when a group of actors deliberately chose the wrong lengths, other subjects began to waver in consciousness and conform to their incorrect answers. Initially, they would resist, showing confusion and discomfort, but after a few times, they would succumb to the group’s opinion, usually displaying a visibly deflated expression. Although “cognitive conformity” and “normative conformity” are clearly two heterogeneous forms of conformity, both cases effectively demonstrate how easily people can negate their initial fundamental beliefs.

Throughout history, ancient and modern, it is not difficult to find that “mobs” often, due to a lack of “wisdom,” easily submit when facing authority, succumbing to collaboration in harming innocent victims without critical thinking. Although this is exhibited in extreme madness, it reveals an inherent servility. From another perspective, the destruction caused by the mob can only be a network of hatred, creating a more violent, oppressive, and unshakable ideological curtain.

Fascists extensively discuss cultivating strong moral qualities, hard work, and family values. They propagate an ideology of order and obedience, expecting people to align with the leadership, while questioning and criticism are seen as “enemies.” It seems that since the advent of authoritarianism, we have understood the sad fact of the weakness and evil in human nature. The progressively developed industrial society, aided by technological and rational revolutions, gradually becomes a new form of authoritarian society, where people are losing critical and transcendent capabilities, lacking the ability to think and reflect, and incapable of taking responsibility for their actions or inactions, becoming “one-dimensional individuals.” Placing a group of ordinary people in an unfamiliar and frightening environment, with little or no constraints, coupled with time and patient waiting, they will inevitably shed their original benevolent appearance.

4. Solutions

Discussing politics is an exceptionally challenging endeavor, particularly in an era of political polarization. Few things can arouse passionate love and hatred as intensely as politics does, turning strangers into allies and friends into enemies. Reading the history of the French Revolution, I was astonished to find that Robespierre was once an opponent of the death penalty, but within a few years, the Jacobin regime he led transformed into a symbol of the guillotine. Reading the history of the Nazis, I saw many claiming that the invention of gas chambers actually made death more “humane” — such cruelty unexpectedly appearing in the name of “humanity.” It seems that politics is a distorted stage for all relationships, all morals, and all concepts; politics always brings about dislocation, forever causing misunderstandings in the process of understanding politics.

However, we must still attempt to understand politics because it holds the source of our destiny. [14] The fundamental reason for the existence of political space lies in the fact that politics encompasses space. Elton points out: not only is space political, but politics is also spatial.

All of human history proves that there is no abstract human nature. “Human social characteristics will change with changes in sociality, and concepts of good and evil will also change.” [18] Marx once said, “The entire history is nothing more than the continuous change of human nature.” [19] However, human progress and the loss of humanity often go hand in hand. The world and the people controlled by the world are absurd, indifferent, and incomprehensible. For us as individuals, in the face of such a societal world, humans are small, lonely, and even incapable of mastering their own lives. Therefore, when desires are no longer concealed and are fully unleashed, we, as humans, are very prone to vividly manifest the darker side of human nature.

4.1. Emphasizing Quality Education to Guide Students in Establishing Correct Values

The subject of applied spatial politics is humanity, and the period of studenthood is a crucial time for the formation of individuals’ perspectives. Issues of political ethical alienation arising from authoritarianism and authoritarian politics are, to some extent, related to the depth of people’s understanding of spatial politics. The deeper the understanding of spatial politics, the better individuals can navigate and even avoid certain alienation challenges. Conversely, shallow understanding may lead to self-disorientation and susceptibility to manipulation when avoiding discussions on numerous issues.

Universities, as “micro-societies,” share a composition structure highly similar to the broader society. However, for the primary component of universities – the students – their developmental environment tends to be “mild,” and the array of problems they face is relatively “simple.” The distinctive nature of the student community implies diverse perspectives on the same matters. It is advisable for university students to approach historical research and political ethical issues with the correct legal attitude. Universities should adopt the right stance and appropriate measures, establishing teaching spaces that cultivate and exercise students’ independent thinking abilities. Efforts should be made to actively overcome fear and embrace challenges.

Often, individuals struggle with self-recognition, clouding their self-awareness and losing a sense of direction. Consequently, alternative methods are sought for self-definition. The Nazi regime, for instance, achieved control by negating and destroying all loyalty relations between individuals, plunging them into complete isolation. People unquestioningly dedicated their entire, absolute loyalty and obedience to the Nazi ruling power. Therefore, it is imperative to keep pace with the trends of the times, ensure the smooth progress of citizens’ quality education, guide students in establishing the right values, and use universities as a catalyst to influence society positively. This involves strengthening the promotion of political, moral, and ethical awareness, fostering independent thinking skills, and consolidating the foundational awareness of humanity’s common existence.

4.2. Seeking a Balance Between Social Systems and Moral Ethics

The issue of political-ethical alienation fundamentally arises from human alienation. As spatial politics continuously advances with the progress of modern society, becoming increasingly sophisticated, it serves as an integral part of the superstructure. To effectively prevent and reduce the problems caused by political-ethical alienation, it is essential to adjust irrational social systems.

Morality resides in people’s hearts, reflecting inner goodness and conscientiousness. Adhering to morality is an expression of self-discipline, while social systems have a certain coercive nature. The combination of these two reflects a balance between strength and gentleness, aiding us in clarifying what should not be done, handling the relationship between rights and obligations, and courageously assuming responsibilities.

Whether laws or systems, they are formulated according to human will and implemented by individuals. Due to various objective constraints and the limitations of human cognitive abilities, system formulation cannot be flawless, and the implementation process may vary among individuals, leading to deviations or mistakes. Excluding emotional factors does not guarantee the impartiality of law enforcement officials. Those truly committed to impartial law enforcement are not the heartless and indifferent individuals as commonly imagined. Although systems and emotional moral ethics differ, they are not entirely opposed or incompatible.

Those in office must adhere to the moral bottom line of governance, comply with political ethics, develop strong capabilities, and simultaneously insist on confining power within the framework of systems. This ensures the creation of a comprehensive mechanism where corruption is neither dared, nor allowed, nor easily achieved, subjecting power to effective constraints such as anti-corruption mechanisms. Millions of citizens should resist servility, uphold independent thinking, refrain from using new-era cyber weapons like keyboards to spread false propaganda and hatred, and avoid becoming an unethical mob.

4.3. Advocating Ethical Reflection and Responsibility for Others

4.3.1. Ethical Reflection

Philosopher Karl Theodor Jaspers insists on sharing the misfortune endured by his wife due to her Jewish identity through the relationship of “I” and “the beloved her,” rather than the distinction between “one kind of person” and “another kind of person.” This approach carries a subtle ethical significance.

Jaspers’s post-war work, “The Question of German War Guilt,” remains relevant for our contemporary study and reflection on Nazi authoritarian rule. In addition, in “The Beyond of Tragedy,” he states, “I am responsible for all the evil that happens in the world unless I have done everything in my power, even sacrificing my life, to prevent it. I am guilty because I am alive when the evil is happening, and I will continue to live. Thus, in all the evil that happens, everyone is an accomplice.” [20] From this, it becomes evident that humanitarian disasters within a nation are the political cost paid by its people for collective moral failure. Humanity requires collective, public, and continuous reflection.

The most wonderful aspect of human nature is its perpetual dynamism. Perhaps the greatness of Milgram’s shock experiment lies not in what it proved but in what it awakened. The awakened human nature is undoubtedly more constructive than narrow-minded discrimination. If discipline and reflection constitute the initial stage of ethical conduct, the mastery and internalization of moral norms by the subject are crucial processes in ethical conduct ethics. The externalization of this into ethical conduct is the key move to overcome the political-ethical alienation predicament.

4.3.2. Responsibility for Others

We can attempt to find a transcendent dimension of responsibility. Emmanuel Levinas’s responsibility for others undoubtedly qualifies as a transcendent solution.

Firstly, the first layer of transcending the “responsibility for oneself” fallacy is to define the other as distinct from oneself and the collective. On one hand, the other is what “I” am not; on the other hand, the other is also distinct from the collective. In self-responsibility and collective responsibility, the self is the agent. However, in responsibility for others, the starting point is the other, surpassing the self. Secondly, the key to fostering responsibility for others lies in intrinsic motivation. Ethical action theory has shown that specific situational contexts determine a person’s specific behavioral choices, i.e., what one feels and thinks at that time. In a sense, the emergence of responsibility for others transcends the dilemma between individual and collective responsibility, while also reminding us of the need to maintain basic respect and awe for others within ethical boundaries.

5. Conclusion

In the context of the typical case of Eichmann discussed in this paper, the dominating force within the entire military is so powerful that any individual daring to confront and challenge it is destined to be crushed into ashes. Perhaps the darkness may not change in the short term, but at least we can choose to lift the gun trigger one centimeter higher when raising our hands. Stanisław Jerzy Lec has a famous saying, “Before the avalanche, a snowflake is just a joyous addition.” If evil is inherent in the system itself, then those who do not understand the consequences of observation and blind obedience, those who succeed through slaughter and repression, do not deserve to play innocent before the stark reality, as everyone within is an accomplice.

Human nature and society sometimes do not align, but human nature must be placed within society. To prevent the recurrence of such horrifying tragedies in the future, what we should be most vigilant against is not the reincarnation of individual figures like Hitler or Eichmann, but the cultivation and formation of a collective irrationality. The contradiction between collective responsibility and individual responsibility is by no means a problem that can be completely solved by determining the responsible subject; it also encompasses issues such as moral capacity, empathy and justice, conflicting interests, and much more. [15]

It must be said that as an “other” space outside capitalist societies, the Chinese characteristic path actually represents the existence of heterogeneous imagination. [18] Openness to the outside world means that our country cannot consistently adopt an avoidant attitude on certain issues. The present time is different from the past, and geopolitical issues have expanded from a single region in Eurasia to a global scale. Isolationism will be an almost insane behavior, which will inevitably trigger a political explosion. If the Chinese path is to continue to maintain rich imagination and vitality, it needs to draw on and apply certain correct ideas of dialectics, not adhere strictly to its own uniqueness, and not avoid common universality but rather combine the two in a dialectical manner. As Harvey stated, “The basis for discovering similarities is to reveal the alliance structure between groups that seem fundamentally different on the surface.” [21] “We must actively seize the ideological high ground and effectively avoid the risk of political alienation in the ideological field.” [22]

I believe in the law, I believe in justice, and I believe that the sword of upholding cosmic justice hangs over each one of us! Only by showcasing the characteristics of the era with the magnificence of an eagle soaring in the sky and the skills of a fish swimming in shallow waters can we possibly maintain a clear sense of self under the control of material desires in the era of high technology. Gradually, we can pursue freedom of body and mind, achieve true justice and righteousness, and avoid sinking into the quagmire of alienation.

References

[1]. Chen, L. (2014). Recognition Politics in the Marginal Space. Journal of Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Social Science Edition, 2014(5), 52-58.

[2]. Tong, Q. (2010). Power, Capital, and Interstitial Space. In Social Science Literature, 93. Beijing: Social Sciences Academic Press.

[3]. Arendt, H. (2020). Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil (Q. Zhou, Trans.). Beijing: Beijing Daily Press.

[4]. Wang, X. (2017). Levinas’ Thought on “the Other.” China Social Sciences Daily.

[5]. Han, Z. (2020). Ethical Critique of Zygmunt Bauman on the Holocaust. Studies on East European Thought, 2020(2), 7-13.

[6]. Sun, T., & Sun, C. (2014). A Brief Analysis of Modernity and the Holocaust. Journal of Chongqing University of Science and Technology, 2014(9), 36-39.

[7]. Sun, Y. (2015). Eichmann in Jerusalem and Arendt’s Theories of Active and Spiritual Life. In Proceedings of Shandong University.

[8]. Deleuze, G., & Guattari, F. (1994). What Is Philosophy? (P. 17). New York: Columbia University Press.

[9]. Wang, X. (2009). Spatial Philosophy and Spatial Politics: Interpretation and Critique of Foucault’s Heterotopia Theory. Tianjin Social Sciences, 2009(3), 11-18.

[10]. Foucault, M. (1999). Discipline and Punish (B. Liu & Y. Yang, Trans.). Beijing: Sanlian Bookstore.

[11]. Young, I. M. (1990). Justice and the Politics of Difference. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

[12]. Guo, K. (2018). A Comparative Study of Marx and Sartre’s Alienation Theory. Century Bridge, 2018(1), 90-92.

[13]. Liao, W. (2016). Historical Logical Generation of Marx’s Alienation Theory. (Unpublished master’s thesis, Hainan University).

[14]. Huang, W. (2021). On Hegel’s Concept of Judaism. (Unpublished master’s thesis, Jilin University).

[15]. Li, J., & Li, H. (2008). On the Dilemma of Administrative Loyalty and Its Resolution: A Case Study of Eichmann’s “Banality of Evil.” Journal of Hunan Normal University, Social Sciences Edition, 2008(3), 35-39.

[16]. Xiao, H. (2001). Bottom Line Ethics and Sin Responsibility—A Review of the Trial of Adolf Eichmann. Open Times, 2001(10), 97-102.

[17]. Bauman, Z. (2011). Modernity and the Holocaust (Y. Yang & J. Shi, Trans.). Nanjing: Yilin Press.

[18]. Chen, X. (2013). Several Issues to Be Noted in Current Marxist Studies. Beijing Daily, 2013.

[19]. Marx, K., & Engels, F. (Selected Works, Vol. 4). Beijing: People’s Publishing House.

[20]. Jaspers, K. (1998). The Tragedy’s Transcendence. Beijing: Workers Press.

[21]. Harvey, D. (2015). Justice, Nature and the Geography of Difference (D. Hu, Trans.). Shanghai: Shanghai People’s Publishing House.

[22]. Pan, K., & Wang, D. (2016). Political Alienation under the Background of Western Capital Power. Scientific Socialism, 2016(3), 149-153.

Cite this article

Xinyu,Z.;Jiexiong,T. (2024). Research on Political Ethical Alienation in the Space of the Other — Starting from Adolf Eichmann. Communications in Humanities Research,27,195-208.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Interdisciplinary Humanities and Communication Studies

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Chen, L. (2014). Recognition Politics in the Marginal Space. Journal of Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Social Science Edition, 2014(5), 52-58.

[2]. Tong, Q. (2010). Power, Capital, and Interstitial Space. In Social Science Literature, 93. Beijing: Social Sciences Academic Press.

[3]. Arendt, H. (2020). Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil (Q. Zhou, Trans.). Beijing: Beijing Daily Press.

[4]. Wang, X. (2017). Levinas’ Thought on “the Other.” China Social Sciences Daily.

[5]. Han, Z. (2020). Ethical Critique of Zygmunt Bauman on the Holocaust. Studies on East European Thought, 2020(2), 7-13.

[6]. Sun, T., & Sun, C. (2014). A Brief Analysis of Modernity and the Holocaust. Journal of Chongqing University of Science and Technology, 2014(9), 36-39.

[7]. Sun, Y. (2015). Eichmann in Jerusalem and Arendt’s Theories of Active and Spiritual Life. In Proceedings of Shandong University.

[8]. Deleuze, G., & Guattari, F. (1994). What Is Philosophy? (P. 17). New York: Columbia University Press.

[9]. Wang, X. (2009). Spatial Philosophy and Spatial Politics: Interpretation and Critique of Foucault’s Heterotopia Theory. Tianjin Social Sciences, 2009(3), 11-18.

[10]. Foucault, M. (1999). Discipline and Punish (B. Liu & Y. Yang, Trans.). Beijing: Sanlian Bookstore.

[11]. Young, I. M. (1990). Justice and the Politics of Difference. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

[12]. Guo, K. (2018). A Comparative Study of Marx and Sartre’s Alienation Theory. Century Bridge, 2018(1), 90-92.

[13]. Liao, W. (2016). Historical Logical Generation of Marx’s Alienation Theory. (Unpublished master’s thesis, Hainan University).

[14]. Huang, W. (2021). On Hegel’s Concept of Judaism. (Unpublished master’s thesis, Jilin University).

[15]. Li, J., & Li, H. (2008). On the Dilemma of Administrative Loyalty and Its Resolution: A Case Study of Eichmann’s “Banality of Evil.” Journal of Hunan Normal University, Social Sciences Edition, 2008(3), 35-39.

[16]. Xiao, H. (2001). Bottom Line Ethics and Sin Responsibility—A Review of the Trial of Adolf Eichmann. Open Times, 2001(10), 97-102.

[17]. Bauman, Z. (2011). Modernity and the Holocaust (Y. Yang & J. Shi, Trans.). Nanjing: Yilin Press.

[18]. Chen, X. (2013). Several Issues to Be Noted in Current Marxist Studies. Beijing Daily, 2013.

[19]. Marx, K., & Engels, F. (Selected Works, Vol. 4). Beijing: People’s Publishing House.

[20]. Jaspers, K. (1998). The Tragedy’s Transcendence. Beijing: Workers Press.

[21]. Harvey, D. (2015). Justice, Nature and the Geography of Difference (D. Hu, Trans.). Shanghai: Shanghai People’s Publishing House.

[22]. Pan, K., & Wang, D. (2016). Political Alienation under the Background of Western Capital Power. Scientific Socialism, 2016(3), 149-153.