1. Introduction

A multilingual environment where more people interact with different language frameworks is fostered by the increasing prevalence of cross-cultural interchange in the fast-globalizing backdrop of modern civilization. In the changing language environment, issues arise about how people's cognitive processes – especially those of people who practice multilingualism—are impacted by the languages they come across. One major worry for those who are multilingual is how can these languages impact their cognitive capabilities or paradigms.

This investigation begins with the Sapir–Whorf hypothesis, a fundamental theory in linguistic relativity that holds that language affects how people think and how they see the world. This study explores the complex relationship between multilingualism and cognition, focusing on the difficulties Chinese students encounter when learning a second language in the context of cognitive linguistics.

This research builds on the Sapir–Whorf hypothesis and draws ideas from a body of literature, and seeks to shed light on the cognitive implications of multilingualism, with a particular focus on Chinese students who have experienced second language acquisition. Through a variety of interviews with members of this population, the goal is to disentangle the complex interactions between linguistic diversity and cognitive linguistics.

This research advances people's comprehension of the wider effects of linguistic variety on cognitive frameworks by investigating the cognitive processes involved in navigating and negotiating many languages. Chinese students' distinct experiences studying overseas act as a microcosm that enables a detailed analysis of the complex interactions between language and cognition. This paper explores the cognitive linguistics difficulties this group has and hopes to offer insightful information that goes beyond theoretical frameworks to enhance scholarly debate as well as practical language acquisition and intercultural communication considerations.

2. Literature Review

The linguistic relativistic hypothesis, often known as the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis, proposes that individuals who speak various languages have essentially distinct thought processes and reality conceptualizations. This approach holds that a language's limitations as well as possibilities influence how its speakers see and comprehend the world, perhaps resulting in distinctive cognitive patterns and viewpoints. [1, 2]. The proposal holds that the semantics of a language can affect the way in which its speakers perceive and conceptualize the world, and in the extreme, completely shape thought, known as linguistic determinism, but thinking patterns or culture does not affect language the other way around [3].

A strong hypothesis of linguistic relativity argues/holds the stance that the structure and vocabulary of a language shape and determine the way its users perceive and think about the world. It proposes that language has such a strong influence on cognition that the language one speaks limits or determines the nature of thoughts.

Nevertheless, some linguists and cognitive scientists have criticized the theory of linguistic relativity, questioning its absolutism. Especially in the development of cognitive science, some scholars have argued that the relationship between language and thought is not absolutely decisive, but more complex and mutually influencing. These doubts challenged the idea of linguistic relativity for some time.

The recent resurgence of research on this question can be attributed, in part, to new insights about the ways in which language might impact thought [4].

As it has evolved over time, many contemporary scholars have advocated a milder version of linguistic relativity, which is known as "linguistic influence", acknowledging that language can influence or shape cognitive processes. Meanwhile, it allows for the coexistence of varying cognitive patterns across different linguistic communities. In other words, this perspective is more open to the idea that other non-linguistic factors also play a role in shaping cognition, such as the contexts, cultural backgrounds, or even emotions and personalities of individuals, etc. Though empirical support for the view that language determines the basic categories of thought has not been found, current research suggests that language can still have a powerful influence on thought [5].

Hence a natural question for the whole field of second language acquisition (SLA) has been this one that asks two things at once: first, how much does the prior language affect the learning and usage of a second language, and second, how much does the prior language's conceptual framework influence the formation of a second language that is compatible with the first [6, 7].

Based on the theory of linguistic relativity, this paper aims to find out how second language acquisition can shape or change people’s thoughts and utterances. Focusing on native Chinese speakers who speak and use a second language in their daily lives, this paper seeks to find out how the context of the second language and other factors have an influence on their thinking patterns, and how they deal with the translation and understanding of abstract concepts between two languages. In addition, this paper will also explore language relativity from the perspective of pragmatics, which is an attempt to provide experimental evidence for whether different thinking patterns can be acquired through second language acquisition or other means [8].

3. Methodology

The primary purpose of methodologies in the research is to empirically investigate the relationship between language and cognition [9]. Researchers aim to provide evidence supporting or refuting the influence of language on thought processes, contributing to a nuanced understanding of the complex interplay between linguistic structures and cognitive functions. Eight interviews in total, with students who have experience of studying and living in foreign countries were conducted, and recordings were transcribed and analyzed using qualitative text analysis.

3.1. Setting of Interview

The setting of questions is based on the study and the research conducted by Boroditsky, the main purpose is to gain an in-depth understanding of the interviewees' language background, language learning process, and life and learning experience in different language environments, and also try to understand the interviewee's linguistic experience in multiple contexts and the impact of language on their personal and professional development [10].

3.2. Ethics

All respondents participated in the interviews knowingly and voluntarily, and at the beginning of each interview, respondents received verbal information about the purpose and content of the research, as well as a description of the ethical rules used in the research, including informed consent and voluntary participation.

All participants have been informed and accepted to have the interviews recorded, and the findings will be published anonymously.

3.3. Recruitment

The selection of participants is based on a purposeful sampling method. The purpose of recruiting interviewees is to reflect certain differences in three aspects: language ability, length of life experience in a foreign language environment and the region where they live, so as to investigate the different performance of subjects with different language levels in the use of their second language.

The interviewees were all Chinese students with overseas study and living experience, and the duration of living in a second language context ranged from one to three years. A total of eight interviewees were recruited, five from English-speaking countries, two from French-speaking countries and one from Spanish-speaking countries (see Table 1). All have experienced cultural and linguistic diversity and the psychological transfer of being an international student. The experimenters found the interviewees through personal contacts, and the subjects who were interested in participating in the interview were informed and volunteered.

Students were recruited through personal contacts made with the interviewer. Students were supposed to have experience studying and communicating with classmates and in diverse classrooms. Besides, they should variate in gender and age. No student refused to participate in the interview.

Table 1: Background Information of the Eight Interviewees

Name | Age | Language* | Time abroad | Location | Major/Occupation | Time for SLA | Frequency of SL use |

A | 24 | M/E/C | 12 months | HK | Laws/ International Economy | 21 yrs | Everyday |

B | 24 | M/E/F/J | 24 | UK | Urban Economic Development | 17 | Everyday |

C | 24 | M/F/E | 36 | France | Data Science | 6 | Everyday |

D | 24 | M/E/K | 12 | UK, Australia | Pharmaceutical Formulation and Entrepreneurship | 17 | Everyday |

E | 24 | M/S/E | 3 | Spain | Pharmaceutical Formulation | 18 | Everyday |

F | 23 | M/E/G | 6 | UK | Philosophy/Economics | 17 | Everyday |

G | 24 | M/E/F | 12 | UK | Philosophy/Pharmaceutical | 20 | Everyday |

H | 28 | M/E | 84 | Canada, India, UK | Philosophy/Economics | 17 | Everyday |

*The capital letters in the table are acronyms of various languages. M for Mandarin; E for English; C for Cantonese; J for Japanese; F for French; K for Korean; S for Spanish; G for German.

3.4. Data Collection

The interview was conducted in December 2023, online by telephone and video call. Interviews are always conducted in a private, one-on-one setting, and the average interview lasts about forty-five minutes to one hour. The content of interviews was first recorded and then transcribed into text for analysis. The main purpose is to ensure the quality, validity and comfort of the participants, while facilitating the data recording and subsequent analysis process.

3.5. Data Analysis

The study first analyzed the personal characteristics of eight respondents, including age, language ability, and time spent in a foreign country. A textual analysis of each interview was then conducted to extract key themes in terms of major linguistic challenges, psychological factors, and cultural differences. Through in-depth qualitative analysis of these topics, some common patterns and unique perspectives can be identified. At the same time, the study conducted a statistical analysis of quantitative data on language choice and thinking styles [11].

For example, participant B said that “Japanese would sound more playful or humorous than Chinese to express apology to friends, which would play a role in easing the atmosphere and weakening negative emotions”. This can be seen as one of evidence that the psychological state of language speakers is influenced by the cultural background of the language when they use their non-native language to construct discourse.

Similarly, participant C mentioned the use of the term ‘train’ in the field of computer programming and data processing. In contrast to its common usage and meaning in people’s daily lives, the term ‘train’ used in this field is to refer specifically to the process of feeding data to a computer for analysis and learning. “As a native Chinese speaker, I need to spend more time to re-understand the meaning of this term and compare it with Chinese, because it is different from the concept of ‘train’ that I knew when I learned English in my daily life, and other words are used to refer this process in the Chinese context”. This phenomenon can be defined then as the difficulty of bilingual comparison of abstract concepts.

4. Results and Discussion

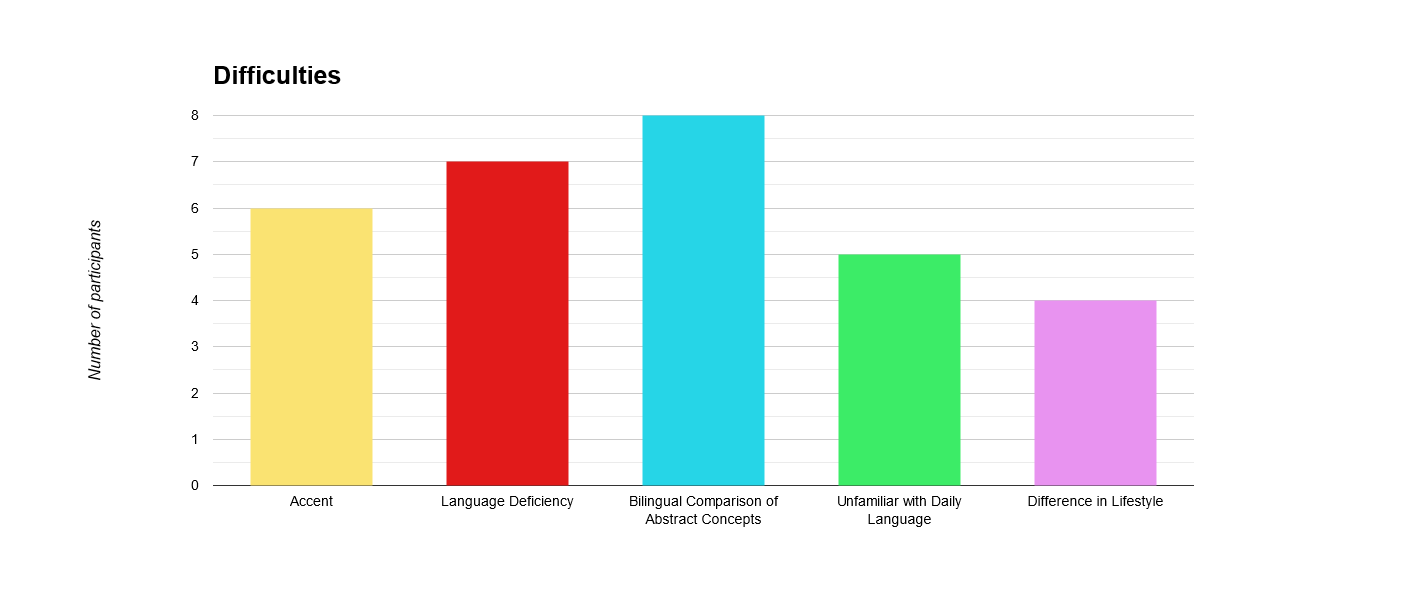

Figure 1: Language Difficulties

As shown in Figure 1, the survey results show that in the process of learning and living in a second language environment, the most significant language difficulties encountered by the subjects come from some difficult concepts between the interviewers' mother tongue and the second language. The differences in these concepts generally come from the cultural and thinking differences caused by the traditions of different countries and regions and different economic, social and legal systems. For example, the crime of ‘common assault’, which exists only in Hong Kong, is not criminalized in the mainland, so it is difficult to understand why an act such as Shouting should be considered a crime under Hong Kong law. The proportion of subjects experiencing such difficulties was even greater than their own language ability and accent problems encountered in the local environment. From this, we can clearly understand that this kind of phenomenon is brought about by the cultural differences behind different languages [12].

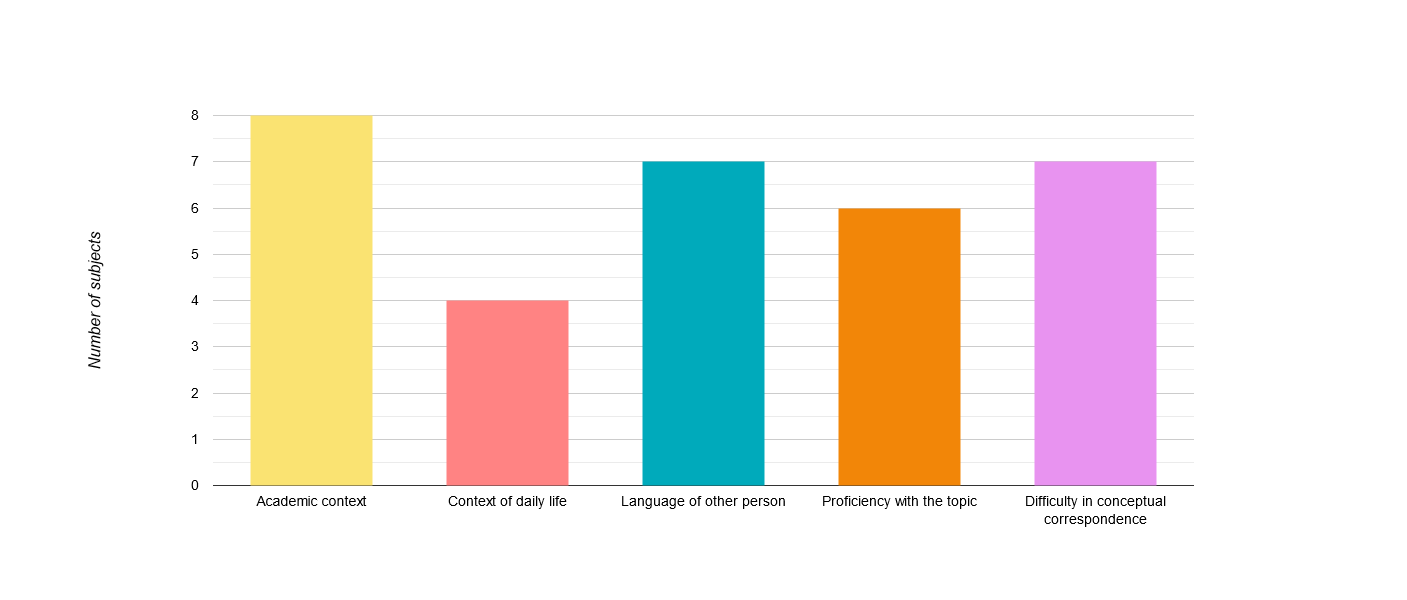

Figure 2: Psychological Concerns

Figure 2 demonstrates the main psychological reasons for subjects to choose their native language or non-native language for thinking before uttering in the second language environment. The context of a conversation has always been regarded as one of the most important psychological factors. More than 75% of the participants said that the language environment and the common language of the people they are communicating with are more important influencing factors. During communication, pressure from context and other objects may force or encourage the subject to construct utterances in the corresponding target language. Apart from that, as discussed before, difficulties in conceptual correspondence can also be found, especially in the dialogue process of academic discussion.

In addition, another finding of the study is that participants generally agree that different languages may be suitable for different emotions and expressions, while ensuring that the person communicating with them can understand the corresponding meaning of the language used. 75% of the respondents believe that languages such as English and French are more suitable for expressing intimacy and positive emotion, such as "Je t’aime". The reason is that in the cultures of Asian countries, such as China, Japan and South Korea, which are deeply influenced by Confucianism, intimacy and positive emotional expressions are often suppressed to a certain extent. Therefore, the use of non-native language to express will weaken the emotional color to some extent. Similarly, through exposure to books, films, etc., from other countries, more than 50% of students believe that different languages (even those they do not use) can express different types of emotions or feelings. For example, Japanese seems to be more suitable for expressing apology, saying ‘Sumimasen’ as an apology can weaken and ease the degree of conflict, while Korean is more suitable for expressing some negative emotions, such as complaining or angry emotions. The root cause may be that in the process of contact with different languages, the emotional expression of specific words or phrases strengthens and deepens the impression in people's thinking, so it changes the language use habits of the speakers [13]. In addition, the use of non-native language was originally a cultural phenomenon within sub-cultural groups, but with the increasing trend of globalization, this phenomenon has gone beyond its original scope and become another result of global cultural integration.

5. Conclusion

Due to the qualitative analysis method, this study chooses to investigate the psychological concerns of second language speakers in-depth, which may in turn fail to examine the common reasons from a larger research group. Further research is needed on whether different languages are more suitable for the expression and mastery of different concepts. Nevertheless, this research still shows the shimmer light of deeper exploration in this direction.

In conclusion, drawing inspiration from the Sapir-Whorf theory, this study delves deeply into the cognitive linguistics difficulties Chinese students encounter while learning a second language. Conversations with a cohort of Chinese pupils highlight the intricate relationship between linguistic variation and psychological processes. The study emphasizes the significance of conceptual and cultural variations, particularly when it comes to difficult conceptual domains pertaining to social, legal, and cultural contexts.

The results of this study show that Chinese students, due to their innate cultural roots, face the challenge of cultural diversity in the Western world where English and other languages are dominant. The challenge particularly affected the participants' experience of learning and using a second language in their lives. The study also sheds light on the psychological factors in Chinese students' language choice, especially the psychological factors that may exist in language conception and expression when they choose to use their mother tongue or second language. The findings demonstrate the importance of individual differences in language ability, peer pressure, emotion, and context on language use and choice, and demonstrate the study of linguistic adaptability to express emotion in multiple linguistic environments.

Despite its limitations, the study sets the stage for future research efforts and demonstrates the feasibility of exploring how different languages might be better suited to express specific concepts or emotions. As global interconnectedness continues to increase, it is hoped that the implications of this study can guide further research into the complex dynamics of language, cognition, and cultural convergence.

References

[1]. Sapir, E. (1929) The Status of Linguistics as a Science. Language, 5(4), 207-214.

[2]. Whorf, B. L. (1956) Language, Thought, and Reality: Selected Writings of Benjamin Lee Whorf. MIT Press.

[3]. Sharifian, F. (2017) Cultural Linguistics and Linguistic Relativity. Language Sciences, 59, 83-92.

[4]. Dolscheid, S., Shayan, S., Majid, A., & Casasanto, D. (2013) The Thickness of Musical Pitch: Psychophysical Evidence for Linguistic Relativity. Psychological Science, 24(5), 613-621.

[5]. Wolff, P. & Holmes, K. J. (2011) Linguistic relativity. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Cognitive Science. 2(3), 253-265.

[6]. Han, Z. & Cadierno, T. (2010) Linguistic Relativity in SLA: Thinking for Speaking. Multilingual Matters.

[7]. Boroditsky, L., Fuhrman, o., & McCormick, K. (2011) Do English and Mandarin Speakers Think about Time Differently? Cognition, 118(1), 123-129.

[8]. Blomberg, J. & Zlatev, J. (2021) Metalinguistic Relativity: Does One’s Ontology Determine One’s View on Linguistic Relativity? Language & Communication, 76, 35-46.

[9]. Bender, A., Beller, S., & Klauer, K. C. (2011) Grammatical Gender in German: A Case for Linguistic Relativity? Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 64(9), 1821-1835.

[10]. Boroditsky, L. (2001) Does Language Shape Thought? Mandarin and English Speakers’ Conceptions of Time. Cognitive Psychology, 43(1), 1–22.

[11]. Wang, Y. & Wei, L. (2022) Thinking and Speaking in a Second Language. Cambridge University Press.

[12]. Pablé, A. (2020) Integrating Linguistic Relativity. Language & Communication, 75, 94-102.

[13]. Hussein, B. (2012) The Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis Today. Theory and Practice in Language Studies, 2(3), 642-646.

Cite this article

Hao,M. (2024). Linguistic Relativity Unveiled: An Exploration of Language and Cognition in Second Language Acquisition. Lecture Notes in Education Psychology and Public Media,43,201-207.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Social Psychology and Humanity Studies

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Sapir, E. (1929) The Status of Linguistics as a Science. Language, 5(4), 207-214.

[2]. Whorf, B. L. (1956) Language, Thought, and Reality: Selected Writings of Benjamin Lee Whorf. MIT Press.

[3]. Sharifian, F. (2017) Cultural Linguistics and Linguistic Relativity. Language Sciences, 59, 83-92.

[4]. Dolscheid, S., Shayan, S., Majid, A., & Casasanto, D. (2013) The Thickness of Musical Pitch: Psychophysical Evidence for Linguistic Relativity. Psychological Science, 24(5), 613-621.

[5]. Wolff, P. & Holmes, K. J. (2011) Linguistic relativity. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Cognitive Science. 2(3), 253-265.

[6]. Han, Z. & Cadierno, T. (2010) Linguistic Relativity in SLA: Thinking for Speaking. Multilingual Matters.

[7]. Boroditsky, L., Fuhrman, o., & McCormick, K. (2011) Do English and Mandarin Speakers Think about Time Differently? Cognition, 118(1), 123-129.

[8]. Blomberg, J. & Zlatev, J. (2021) Metalinguistic Relativity: Does One’s Ontology Determine One’s View on Linguistic Relativity? Language & Communication, 76, 35-46.

[9]. Bender, A., Beller, S., & Klauer, K. C. (2011) Grammatical Gender in German: A Case for Linguistic Relativity? Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 64(9), 1821-1835.

[10]. Boroditsky, L. (2001) Does Language Shape Thought? Mandarin and English Speakers’ Conceptions of Time. Cognitive Psychology, 43(1), 1–22.

[11]. Wang, Y. & Wei, L. (2022) Thinking and Speaking in a Second Language. Cambridge University Press.

[12]. Pablé, A. (2020) Integrating Linguistic Relativity. Language & Communication, 75, 94-102.

[13]. Hussein, B. (2012) The Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis Today. Theory and Practice in Language Studies, 2(3), 642-646.