1. Introduction

Since its publication, Stanley Milgram’s studies on obedience have received numerous feedback not only in the social psychological field but also in a more public sense [1-3]. The disturbing results shown in the series of experiments throughout the years have revealed how powerful pressure arising from the situational field can apply to a person. Though the most well-known experiment has stressed the importance of situational determinants, it is reasonable to question if different personality characteristics will also result in distinct outcomes [2]. In a subsequent experiment, Milgram and Elms examined whether the personality variables lead to any tendency towards obedience [4]. Through investigation, it is reported that obedient and defiant do exhibit significant differences towards their own father, experimenter, and other authority figures or related concepts, indicating that there exists a probable initial difference between the two groups. It is not the first-time obedience has been linked with parental behaviors. Despite its universality, obedience has been considered more of a nurturing product than an intrinsic trait of human nature. Obedience has always played a crucial role and can be seen as an indispensable quality in parent-child relations worldwide.

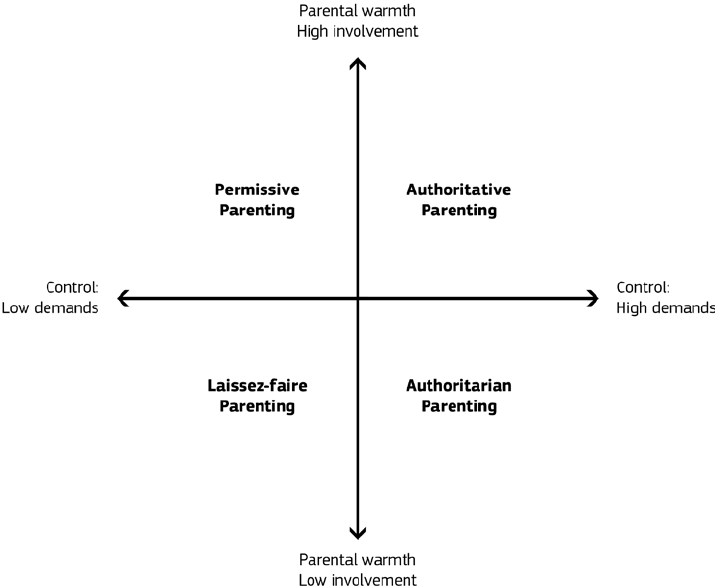

Due to its significance in the upbringing of children, parental behaviors have gathered attention among scholars throughout the years, and several theories have been developed on the subject. In the past century, Baumrind has categorized parenting styles into three, respectively authoritarian, authoritative, and permissive parenting [5-7]. Two elements of parenting styles are spotted during identification regarded as demandingness and responsiveness in further research and hence adding one more dimension, rejecting/neglected parenting, to the original structure [8]. Demandingness is defined as parents’ willingness to set bounds for their children’s behavior, including their tendency to control and enforce certain treatment while subjects violate rules. Responsiveness, on the other hand, refers to the extent of awareness that gives rise to a child’s physical or mental needs. Figure 1 offers a visual overview of these four dimensions of parenting styles.

Though multiple accounts for the formation of parenting, cultural difference certainly associates with it from a more subconscious level. For example, Asian cultures tend to emphasize group harmony and “fitting in” more than individual development. People are also taught to restrain their emotions, mainly since digesting emotions on one’s own is usually seen as a sign of self-control, strength, and patience [9]. Under these traditional cultural influences, Asian parenting styles are most likely to be authoritarian [10-11].

Figure 1: The four parenting styles

Along with the rising discussion towards Milgram’s investigation on unveiling the nature of obedience, a great proportion of criticism arises from the perspective of ethnicity. Scholars express certain concerns about the long-term negative phycological impact on participants for intentionally harming others. Arguments include insufficient dignity given to the subjects during the process as the realization of the experiment setting would bring a sense of being fooled, not being able to express their unpleasantness towards researchers, and the lengthy step to withdrawal tends to discourage participants [12]. Given the rise to these problems, few reproductions of Milgram’s experiment have been carried out around the world. Meanwhile, the obedience experiment replicated by Jerry Burger has provided us with a more ethical approach to running the obedience experiment [13].

In this study, we aim to explore the relationship between one specific parenting style and obedience in the cultural background of middle-class mainland China. We are going to adopt Baumrind’s parenting model while focusing primarily on the authoritarian parenting style, which corresponds to the low responsiveness and high demandingness type. Our basic assumption is that adolescents receiving an authoritarian parenting style would lead to more obedience towards authority figures in later years. Moreover, we will further explore whether self-esteem could be an intermediate factor during its developing process.

2. Method

100 undergraduate students aged from 18 to 22 will be selected from universities in China. No restrictions are applied to gender in this design since Milgram has presented in his follow-up studies that the level of obedience shown in female attendants was essentially identical to the behavior of men, with extra evidence shown in experiments presented by the successor [13,14]. The selection of subjects will be evenly distributed geographically, and social and economic backgrounds are expected to be held at the same level (middle class in our case). During the recruitment, participants will be asked about their current majors and whether they have previously taken any psychology classes. Students who have taken courses on psychology will not be included in our study. This process is designed to eliminate people who may have relevant knowledge associated with Milgram’s experiment, as the recognition would have a certain impact on results. Based condition of our experiment will be largely established upon Jerry Berger’s partial replication of Milgram’s original investigation [13].

The experiment will take place on a university campus. On arrival, participants are given a demographic form containing a series of questions, including gender, age, permanent city of residence and the subject of degree. After completing the form, each participant will be escorted into the room and introduced to the experimenter. A minute later, the confederate will be escorted to enter the same room. Then the experimenter will give general guidance that is similar to the one used in Milgram’s research, mainly describing the purpose of the research to be examining the effect of punishment on learning. The experimenter will next instruct the participant that one would be the ‘Teacher’ and the other one would be the ‘Learner’. The decision of role will be made through random drawing; however, the distribution of roles is, in fact, rigged; therefore, the subject will always be the teacher and the confederate always the learner. Immediately after the arrangement, the experimenter will bring the two to the adjacent room and ask the confederate to sit in the chair. The latter’s arm will be strapped onto the armrest of the chair and have electrodes attached to one of their wrists. The subject is then given a list of word pairs (e.g. red – book) and told their task is to first read out these pairs to the learner and next, test the learner on their memory by reading the first word in the pair (e.g. red) with four other words, among which contains a word in the original pair. After each delivery of the testing sequence, the learner needs to give a response of choosing the associated word that appeared before using the four switches attached to the box placed on the table in front of them. The experimenter will point out that false responses would activate electrical shocks applied to the learner as a form of punishment. Also, the experiment will not stop until the learner has fully gone through the list of word pairs. The experimenter could show a small demonstration of such a procedure for clarification and give an example of a shock to the Confederate. At this point, the confederate will mention that they have detected a minor heart condition and express concern about the intensity of electric shocks. The experimenter will subsequently indicate that the following shocks could be painful but are controlled within the safety range.

Soon after, the experimenter will escort the subject back to the lab room. A shock generator built accordingly to Milgram’s description is placed on the table in front of the subject. The electrical shocks can be generated from 15 volts to 450 volts, and 30 switches are rested on the machine. Each switch corresponds to an interval of 15 volts. The experimenter will then provide instructions on how to use the shock generator and tell the subject that they need to turn up one switch on the generator each time the learner gives an incorrect answer. What’s more, the subject is told to speak through the one-way microphone the number of volts administered. During the experiment, the confederate will give correct and incorrect answers identical to the arranged schedule designed in Milgram’s study. Additionally, two clinical psychologists are engaged to observe the participants’ performances from another room through the glass window along the process. One of them is assigned to determine whether the subject’s status (both mentally and physically) is allowed to continue at each stage and the other one will note down the voltage where each participant started to display any signs under pressure through administering punishment. Furthermore, the entire operation of the experiment will be audio recorded for analysis purposes.

Each vocal response of the learner is consistent with a distinct voltage level. When the voltage reaches the 75-volt switch, the participant will hear “a small grunt” through the wall. Beyond this point, every grunt was slightly louder than the previous one after each time participants delivered the voltage. By the time the subject goes for the 150-volt switch, a yelling saying, “Enough! My heart starts to feel uncomfortable. Please let me out!” will be heard through the wall. It is worth noting that all oral feedback received by the subject is pre-recorded by the confederate and is stored as audio files to be played when participants turn on the matching switch.

The experiment will be marked as end under either of the following three conditions: a) the subject turns up the 150-volt switch and reads the next pair on the list; b) the subject refuses to continue after hearing all possible feedback from the experimenter; c) the clinical psychologist suggests that the subject’s condition is no longer suitable for progression. Whenever the subject turns to the experimenter for advice on whether to carry on, four different responses directly taken from those that appeared in Milgram’s experiment will be offered to them, aiming for the subject to proceed. As soon as the experiment is labelled as finished, the experimenter will promptly bring the participant to the adjacent room to reveal that no electrical shocks are actually given to the learner.

There is a follow-up session implied to gather more qualitative data from participants and meanwhile provides a chance for them to express their feelings to release some pressure results from the experiment. We will one by one ask the participants to self-reflect on when they began to feel tense, specifically at which switch during the procedure, if possible. Once such information has been gathered, parenting-style questionnaires are handed out to participants to complete. The parenting style survey is developed based on the Parental Authority Questionnaire designed by Buri, J.R. [15]. A few alterations have been made accordingly. Since we have narrowed down our focus to one specific parenting style, namely authoritarian, all 10 questions are designed to measure how authoritarian the parenting style one receives using two scales. The survey starts with 5 questions examining the demandingness of parental behaviors received by the participant, and another 5 questions are listed to reflect the responsiveness of their parents. Each question will be graded from 1 to 10 on agree or disagree with an overall score of 100. Due to the characteristic of such parenting style, scoring follows the rule that the lower the responsiveness is, the higher the score is. Higher demandingness also produces higher scores. In that case, the overall score is positively related to the degree of authority.

Obedience evaluation attempts to take a further step up from the original. Instead of simply using the width, namely the maximum electrical shock the subject is willing to give, as measurement criteria, I decide to use the depth, which is identified as the willingness to choose obedience under struggle. The idea behind the latter one is that participants may not show hesitation or do not see the process as a forceful task in the delivery of the first few shocks. However, we can assume that certain awareness of obedience towards authority appears at a certain point (that time is determined by individual differences), and beyond that point, the subject is now facing a dilemma that requires them to consciously make a choice upon the situation. We would like to find that node and strive to combine it with the maximum electrical shock as a reference system for obedience. Therefore, in addition to recording the voltage our subjects proceed towards the end of the experiment (denoting as the Overall Obedience), we will combine it with what has been collected from both participants and the clinical psychologist. A variable named Reaction Time will assist us in determining the exact point the participant entered the state where the punishment is operated under pressure. After analyzing the audio recording of each participant, we may produce a set of data defined as the Reaction Time through each delivery, which calculates every time interval from the moment participants receive the learner’s response to the point when they administer the electrical shock. We are expecting there to be a relative rise in the length of Reaction Time (e.g. at 75 volts, the patient slows down/hesitates) part of the way. If multiple rises are spotted in the data, we will consider only the first significant rise. Then, we will take its matching volts together with the self-reflect response we collected from participants in the follow-up session and the observation of the clinical psychologist and take the median of all three to be the point, defining as the Entry State, where participants enter the state of operating under pressure. The interval of volts between the Entry State and the Overall Obedience is what we call the Obedience Under Pressure. Using the ratio of Obedience Under Pressure and Overall Obedience, the measurement of obedience will contain within the range of 0 and 1. The more the score approaches 1, the more intense the obedience is (i.e. The subject is willing to last longer under pressure).

3. Possible Intermediate Variable

In our study, we also intend to explore the possible factor which could influence the relationship between two variables, one of which is self-esteem. Earlier studies have revealed that parental behaviors are related to self-esteem. Coppersmith has identified four primal factors that build the foundation of one’s self-esteem, and parents play a crucial role in each of them [16]. It was further noted that drawing clear limits, having high expectations for children, and appreciation towards one’s originality during childhood tends to result in higher self-esteem of children. We presume that an extremely strict parenting style with low expectations for children would lead children to question their value. Although in a later investigation, Rudy and Grusec noted that authoritarianism was not associated with self-esteem in either collectivist or individualist groups, there was still some form of support suggesting that mothers’ emotions and thoughts about their children would be associated with self-esteem [17]. Moreover, we suggest that there might be a connection between self-esteem and obedience. People with lower self-esteem would be more likely to follow instructions and similarly more likely to doubt their own decision-making. Regarding the measurement of self-esteem, we will be using the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale.

4. Result

We presume that the distribution of scores on authoritarian parenting among the 100 students will focus on the slightly higher medium area, which is around 60. This prediction resonates with the findings of Xu et al., which suggests that Chinese mothers had medium scores on the authoritarian parenting scale (M = 2.86 on a 5-point scale) [18]. Steinberg et al. also conclude that authoritative parenting was far rare among Asian Americans compared with children in other regions [19]. Combining such a conclusion with another paper denoting that the authoritative parenting style was inversely correlated with the authoritarian parenting style, we could once more take into the consideration that authoritarian parenting style is rather dominant in mainland China [20]. In Milgram’s original research, sixty-two percent of the subjects followed the experimenter’s commands till the end [2]. While all participants in the said experiment consist of white males, we may predict that Asians, specifically Chinese students, which are raised in a more demanding environment, would show slightly more tendencies of obedience. Few research has touched on such a topic. A previous study focused on elements that may influence young Chinese children’s concepts of authority, revealing that obedience to authority was necessary for moral and conventional events [21]. At the same time, we might foresee that Chinese participants will attempt to communicate with the experimenter more to reach a balance between their own moral code and demands from authority as researchers also suggest that young Chinese children are attempting to negotiate, striving to be considerate for all parties when encountered issues [22]. Recently, more researchers have set their eyes on the topic of examining Chinese children’s self-esteem, as most studies on self-esteem were focused mainly on children with Western cultural backgrounds. In their 2001 study, Wang and Ollendick investigated the development of self-esteem from a cross-cultural perspective in Chinese and Western adolescents [23]. They suggest that Chinese children, similarly to the Westerns, will undergo a transition of sense of self-esteem throughout time, from primarily depending on caregivers’ feedback to a more independent self-evaluation. However, as the Chinese culture has a strong emphasis on the concept of filial piety, it is predicted that the average magnitude of difference between earlier years and later adolescents in Chinese would be less compared to the Westerns. Furthermore, they point out that the first essential step towards understanding the construction of self-esteem of Chinese children is to examine their parents’ expectations at various stages. Twenty years later, a study, which lasted over a year, examined 825 youth in US and China and reflected on their self-esteem and parents’ mental control. The result indicates that American students have shown a higher average level of self-esteem despite the confidence of students from both regions gradually decreasing. In the paper, Chen, Ng, and Pomerantz further revealed that Chinese parents had gained more control along the process, which is opposite to the case in the US [24]. Hence, we may predict that the overall self-esteem among Chinese university students would scatter along the scale while gathering more around the lower area. Moreover, we anticipate a negative correlation between self-esteem and obedience. Little study is focused on these two components, and data is less than expected. Meanwhile, Gudjonsson and Sigurdsson ran an experiment that uncovered that low self-esteem was one of the two best predictors of compliance among objects [25]. Though we only have a limited view as compliance is inadequately the same as obedience, nevertheless, we found it enlightening that the level of self-esteem could affect one’s psychological state under stressful conditions.

5. Limitations and Future Directions

5.1. Longitudinal Effect

One limitation that stems from such a design is the longitudinal effect. Adapting from Jerry Burger’s research design, we lower the maximum shock from 450V to 150V for ethical concerns as he observes that 79% of the participants who reach 150V proceed to the end (450V). Furthermore, as denoted in Twenge's paper, the following study suggests that 150 volts is a critical turning point, as well as a reliable predictor of obedience [26]. Nonetheless, the said observation is based on the original Milgram study, which was published in the 1960s. It is equitable to argue that decades later, the same percentage may no longer be equivalent to the obedience rate as the threshold may shift due to culture change etc. A particular example could be that modern people have become exposed to more violent content, especially through adolescence, compared to past days owing to technological advancements and access to social media. A recent study shows that frequent exposure to violence across media is associated with emotional desensitization [27]. Hence, in-depth studies could focus on the changing threshold of tolerance towards modern citizens, providing a more solid and accurate base for the study of obedience.

5.2. Essence of Obedience

In the study, we expect the subject to recapture his own will and act out towards the circumstances, and our design (especially the method for determining obedience) focuses mainly on the conscious part of such action. However, obedience, in daily circumstances, may not involve internal struggle and performs subconsciously. In Milgram’s series of experiments [1-3,27], one of the variations is to change the location (from Yale University lab to a modest office) to rule out the university’s prestige as a potential factor. Although the result suggests differences are not statistically significant, it raises concern that factors that influence obedience may well not be limited to the experiment itself but show signs even before the experiment starts. Elements including environment, the image of the scholar, the proximity of authority figures, etc., are not uncommon for social activity. As social norms shape perspectives of authority, the tendency for obedience varies correspondingly. To take a step further, future research may follow down the route and shed light on the motive behind one’s action. Several attempts might have been made around such a topic. However, due to its complexity, different combinations of motive may lead to the same behavioral outcome, and future studies could set their mind on designing new experiments towards obedience to decode them separately.

6. Conclusions

This study presents a new method of evaluating obedience based on Burger’s replication of Milgram’s experiment. A new factor, ‘Reaction Time’, is included in our measurement, aiming to present a more precise result on the subject’s degree of obedience. Our subjects are educated class in/around their 20s in mainland China, and we attempt to use both experiment and survey to investigate the relationship between authoritarian parenting style and obedience. We expect it to be a slightly positive relationship. On that basis, we additionally include a questionnaire rating self-esteem to discover if the latter plays an intermediate factor in such a relationship.

Nearly 60 years have passed since Milgram introduced his study, and to this day, its groundbreaking results intrigue researchers in the field. It demonstrates the power of authority on ordinary people, who can be pushed to act unexpectedly and far enough to even be harmful to others in given circumstances. The findings overthrow what used to believe as the key to one’s action and signify the importance of the situation. The twentieth century has witnessed technical improvement, and digital devices have flooded people with an enormous amount of information. It is for future discussion to reveal if such change would enhance the capacity of authority or more defiant would appear.

References

[1]. Milgram, S. (1963). Behavioral study of obedience. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 67(4), 371.

[2]. Milgram, S. (1965). Some Conditions of Obedience and Disobedience to Authority. Human Relations.

[3]. Milgram, S. (1974). Obedience to Authority: An Experimental View. Harper & Row.

[4]. Elms, A. C., & Milgram, S. (1966). Personality characteristics associated with obedience and defiance toward authoritative command. Journal of Experimental Research in Personality, 1(4), 282–289.

[5]. Baumrind, D. (1971). Current patterns of parental authority. Developmental psychology, 4(1p2),

[6]. Baumrind, D. (1989). Rearing competent children. In W. Damon (Ed.), Child development today and tomorrow (pp. 349–378). Jossey-Bass/Wiley.

[7]. Baumrind, D. (1991). The influence of parenting style on adolescent competence and substance use. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 11(1), 56–95.

[8]. Maccoby, E. E., & Martin, J. A. (1983). Socialization in the Context of the Family: Parent-Child Interaction. In P. H. Mussen, & E. M. Hetherington (Eds.), Handbook of Child Psychology: Vol. 4. Socialization, Personality, and Social Development (pp. 1-101). New York: Wiley.

[9]. Kawamura, K. Y. (2012). Body image among Asian Americans. In T. F. Cash (Ed.), Encyclopedia of body image and human appearance (pp. 95–102). Elsevier Academic Press.

[10]. Chen, C., Lee, S.-y., & Stevenson, H. W. (1995). Response style and cross-cultural comparisons of rating scales among East Asian and North American students. Psychological Science, 6(3), 170–175.

[11]. Leung, K., Lau, S., & Lam, W.-L. (1998). Parenting styles and academic achievement: A cross-cultural study. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 44(2), 157–172.

[12]. Baumrind, D. (1964). Some thoughts on ethics of research: After reading Milgram's "Behavioral Study of Obedience." American Psychologist, 19(6), 421–423.

[13]. Burger, J. M. (2009). Replicating Milgram: Would people still obey today? American psychologist, 64(1), 1.

[14]. Shanab, M.E., & Yahya, K.A. (1978). A cross-cultural study of obedience. Bulletin of the psychonomic society, 11, 267-269.

[15]. Buri, J. R. (1991). Parental Authority Questionnaire. Journal of Personality Assessment, 57(1), 110–119.

[16]. Coopersmith, S. (1967). The antecedents of self-esteem. San Francisco: W. H. Freeman and Company.

[17]. Rudy, D., & Grusec, J. E. (2006). Authoritarian parenting in individualist and collectivist groups: Associations with maternal emotion and cognition and children's self-esteem. Journal of Family Psychology, 20(1), 68–78.

[18]. Xu, Y., Farver, J. A., Zhang, Z., Zeng, Q., Yu, L., & Cai, B. (2005). Mainland Chinese parenting styles and parent-child interaction. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 29(6), 524-531.

[19]. Steinberg, L., Dornbusch, S. M., & Brown, B. B. (1992). Ethnic differences in adolescent achievement. An ecological perspective. The American psychologist, 47(6), 723–729.

[20]. Huang, J., & Prochner, L. (2003). Chinese Parenting Styles and Children’s Self-Regulated Learning. Journal of Research in Childhood Education, 18(3), 227–238.

[21]. Yau, J., Smetana, J. G., & Metzger, A. (2009). Young Chinese children's authority concepts. Social Development, 18(1), 210–229.

[22]. Yau, J., & Smetana, J. G. (1996). Adolescent–parent conflict among Chinese adolescents in Hong Kong. Child Development, 67(3), 1262–1275.

[23]. Wang, Y., & Ollendick, T. H. (2001). A cross-cultural and developmental analysis of self-esteem in Chinese and Western children. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 4(3), 253–271.

[24]. Chen, H. Y., Ng, J., & Pomerantz, E. M. (2021). Why is Self-Esteem Higher Among American than Chinese Early Adolescents? The Role of Psychologically Controlling Parenting. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 50(9), 1856–1869.

[25]. Gudjonsson, G. H., & Sigurdsson, J. F. (2003). The relationship of compliance with coping strategies and self-esteem. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 19(2), 117–123.

[26]. Twenge J. M. (2009). Change over time in obedience: The jury's still out, but it might be decreasing. The American psychologist, 64(1), 28–31.

[27]. Mrug, S., Madan, A., Cook, E. W., 3rd, & Wright, R. A. (2015). Emotional and physiological desensitization to real-life and movie violence. Journal of youth and adolescence, 44(5), 1092–1108.

Cite this article

Chen,Q. (2024). Obedience and Authoritarian Parenting Style in China. Lecture Notes in Education Psychology and Public Media,44,67-74.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the International Conference on Global Politics and Socio-Humanities

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Milgram, S. (1963). Behavioral study of obedience. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 67(4), 371.

[2]. Milgram, S. (1965). Some Conditions of Obedience and Disobedience to Authority. Human Relations.

[3]. Milgram, S. (1974). Obedience to Authority: An Experimental View. Harper & Row.

[4]. Elms, A. C., & Milgram, S. (1966). Personality characteristics associated with obedience and defiance toward authoritative command. Journal of Experimental Research in Personality, 1(4), 282–289.

[5]. Baumrind, D. (1971). Current patterns of parental authority. Developmental psychology, 4(1p2),

[6]. Baumrind, D. (1989). Rearing competent children. In W. Damon (Ed.), Child development today and tomorrow (pp. 349–378). Jossey-Bass/Wiley.

[7]. Baumrind, D. (1991). The influence of parenting style on adolescent competence and substance use. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 11(1), 56–95.

[8]. Maccoby, E. E., & Martin, J. A. (1983). Socialization in the Context of the Family: Parent-Child Interaction. In P. H. Mussen, & E. M. Hetherington (Eds.), Handbook of Child Psychology: Vol. 4. Socialization, Personality, and Social Development (pp. 1-101). New York: Wiley.

[9]. Kawamura, K. Y. (2012). Body image among Asian Americans. In T. F. Cash (Ed.), Encyclopedia of body image and human appearance (pp. 95–102). Elsevier Academic Press.

[10]. Chen, C., Lee, S.-y., & Stevenson, H. W. (1995). Response style and cross-cultural comparisons of rating scales among East Asian and North American students. Psychological Science, 6(3), 170–175.

[11]. Leung, K., Lau, S., & Lam, W.-L. (1998). Parenting styles and academic achievement: A cross-cultural study. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 44(2), 157–172.

[12]. Baumrind, D. (1964). Some thoughts on ethics of research: After reading Milgram's "Behavioral Study of Obedience." American Psychologist, 19(6), 421–423.

[13]. Burger, J. M. (2009). Replicating Milgram: Would people still obey today? American psychologist, 64(1), 1.

[14]. Shanab, M.E., & Yahya, K.A. (1978). A cross-cultural study of obedience. Bulletin of the psychonomic society, 11, 267-269.

[15]. Buri, J. R. (1991). Parental Authority Questionnaire. Journal of Personality Assessment, 57(1), 110–119.

[16]. Coopersmith, S. (1967). The antecedents of self-esteem. San Francisco: W. H. Freeman and Company.

[17]. Rudy, D., & Grusec, J. E. (2006). Authoritarian parenting in individualist and collectivist groups: Associations with maternal emotion and cognition and children's self-esteem. Journal of Family Psychology, 20(1), 68–78.

[18]. Xu, Y., Farver, J. A., Zhang, Z., Zeng, Q., Yu, L., & Cai, B. (2005). Mainland Chinese parenting styles and parent-child interaction. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 29(6), 524-531.

[19]. Steinberg, L., Dornbusch, S. M., & Brown, B. B. (1992). Ethnic differences in adolescent achievement. An ecological perspective. The American psychologist, 47(6), 723–729.

[20]. Huang, J., & Prochner, L. (2003). Chinese Parenting Styles and Children’s Self-Regulated Learning. Journal of Research in Childhood Education, 18(3), 227–238.

[21]. Yau, J., Smetana, J. G., & Metzger, A. (2009). Young Chinese children's authority concepts. Social Development, 18(1), 210–229.

[22]. Yau, J., & Smetana, J. G. (1996). Adolescent–parent conflict among Chinese adolescents in Hong Kong. Child Development, 67(3), 1262–1275.

[23]. Wang, Y., & Ollendick, T. H. (2001). A cross-cultural and developmental analysis of self-esteem in Chinese and Western children. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 4(3), 253–271.

[24]. Chen, H. Y., Ng, J., & Pomerantz, E. M. (2021). Why is Self-Esteem Higher Among American than Chinese Early Adolescents? The Role of Psychologically Controlling Parenting. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 50(9), 1856–1869.

[25]. Gudjonsson, G. H., & Sigurdsson, J. F. (2003). The relationship of compliance with coping strategies and self-esteem. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 19(2), 117–123.

[26]. Twenge J. M. (2009). Change over time in obedience: The jury's still out, but it might be decreasing. The American psychologist, 64(1), 28–31.

[27]. Mrug, S., Madan, A., Cook, E. W., 3rd, & Wright, R. A. (2015). Emotional and physiological desensitization to real-life and movie violence. Journal of youth and adolescence, 44(5), 1092–1108.