1. Introduction

The following research question aims to investigate whether rejection and childhood abuse during early-stage family communication contributes to Avoidance Personality Disorders under cross-cultural backgrounds. Past studies revealed the topic of how family communications affect Avoidant Personality Disorders, but the ones with the cross-cultural factors are minimal. If the correlation between family communication and Avoidant Personality Disorder is determined, then the ways of decreasing the possibility of this disorder would also be clarified. Previous theories by Jeffrey Young have shown that the development of a personality is based on schemas formed during childhood relationships with people, most frequently with parents. These schemas are a type of cognitive-emotional representation that reflect the knowledge about us in our world [1]. The more the environment disadvantaged a child of its needs, the stronger the schemas become on the negative side. Gradually, the behavioral patterns become more and more defective, creating the basics of abnormal personality traits [2]. Interactions in an independent study [3] (N=127) suggests that pessimism was strongly related to Avoidant Personality traits among those who recalled negative childhood experiences, according to the assessing of negative childhood memories, sensory-processing sensitivity, and pessimism. Undergraduate participants wrote open-ended narratives as a measure of negative childhood memories, which the qualitative data were then evaluated by independent raters. To measure Avoidant Personality features, participants rated the extent to which verbatim BSM-IV criteria suits the description of themselves. Despite the relevance of the works, they did not test how the cross-cultural factor influence negative family communications affect Avoidant Personality Disorders. Therefore, the question remains: Do rejection and childhood abuse during early-stage family communications contribute to Avoidant Personality Disorders cross-culturally? The following research question fits in to the existing bodies of knowledge by acting as a continuation as well as a preliminary verification of the theories, such that the cultural aspect was added. Under both cultures, rejection, and childhood abuse both affect to the development of Avoidant Personality Disorder. While the children growing under American parenting styles are affected by these family factors to a bigger extent compared to Chinese children.

2. Present Work

The aim of the present research was to investigate how negative childhood communications in families affect Avoidant Personality Disorder cross-culturally, and the extent to which the present hypothesis is supported by previous theories. Through a correlational design and by conducting a retrospective study, we asked participants to first input their cultural background from the two options: American or Chinese. Then participants viewed, and answer questions based on the Five Factor Avoidant Assessment scale [4] at their home. After a 2-hour break since the survey has ended, participants will then be answering The Childhood Experience Questionnaire-Revised (CEQ-R) interview [5], which is a semi structured interview that questions about the occurrence of positive and negative experiences encountered during three age periods at childhood (0-5, 6-12, 13-17 years). Through a retrospective view, participants will lastly be writing short open-ended narratives that reflects their childhood memories related to negative parental communications. They will be given a 2 -sided piece of paper with blank lines on it and will be given instructions on how to make a response. This design has several advantages. First, it allows to investigate the initial question of whether, and to what extent, there is a relationship between Rejection and Childhood abuse during early-stage family communications and Avoidant Personality Disorder under a two different parenting cultures. Through answering questions and writing open-ended narratives about negative childhood communications in family, would be the evidence that rejection and childhood abuse does correlate with Avoidant Personality Disorder. Second, through a retrospective-questionnaire design, the presence of more than two variables will not cause the results to be difficult to interpret. For instance, even though the cultural variable was added, participants will only need to select the culture they grew up in and this choice will not be easily affected by other factors due to how direct it is. It is predicted that with respect to rejection and childhood abuse, which are hypothesized to be correlated positively with Avoidant Personality Disorder, the results will support the hypothesis (Hypothesis 1). Avoidant Personality Disorder, as conceptualized by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth edition (DSM-5), is referred to as a by “extensive avoidance of social interactions driven by fears of rejection and feelings of personal inadequacy” [6]. Howe et al has made demonstration of how early experiences of rejection causes lasting effects on how individual view themselves, and if people saw rejection as a reflection of the inadequacy of their abilities, would lead to more sustained negative impacts on future perceived rejections [7]. In turn, this will lead them to frequently avoid socializing. Pessimism was strongly related to Avoidant Personality traits among those who recalled negative childhood experiences, according to the assessing of negative childhood memories, sensory-processing sensitivity, and pessimism. It is also predicted that the children growing under American parenting styles are affected by these family factors to a bigger extent compared to Chinese children. Asian student samples have the highest rate on the Authoritarian parenting style of the 3 parental control styles (Authoritarian, Permissive, Authoritative), while the American student sample act completely the opposite [8]. In other words, if the cultural norm is used to Obedient family communication, then children under that background would be consider the views of someone who has the same “authority” or rights as themselves, such as their peers, as more important. Thus, it is hypothesized for a more modest correlation under the Chinese parenting background (Hypothesis 2).

3. Experiment 1

3.1. Method

We report all measures, manipulations, and exclusions here. This study will be approved by and carried out in accordance with the recommendations of the Institutional Review Board for human participants with written informed consent obtained from all participants.

3.2. Participants

One hundred and seventy-eight adult participants (89 males and 89 females, mean age = 21.56 years) growing under a Chinese parenting background, and one hundred and seventy-eight adult participants (89 males and 89 females, mean age = 20.95 years) growing under an American parenting background will be recruited for participation in exchange for completing the PDQ-4 measure of Avoidant Personality Disorders (Measure 1), the online questionnaire (Measure 2), and the open-ended narratives (Measure 3). The total sample size will be 356. The study invited all participants who met the pre-determined selection criteria (see Procedures and Measures for descriptions) to complete the two questionnaires and the open-ended narratives at home to all participants who accepted the invitation within two months. Data collection is stopped at the end of two months after the first study was conducted (participants who failed to participate during the first study can also reach out and finish it later within the two months). Participants will be excluded if they do not fit the age requirement (18-24), did not experience (or failed to recall) frequent signs of negative childhood memories, or did not receive an education level more than high school.

The primary hypothesis involved assessing how rejection and childhood abuse contribute to Avoidant Personality Disorder along with the cross-culture factor (Chinese background and American background). A power analysis using the software package G*Power will be performed [9]. The results indicated that with N=356, the experiment could detect an effect size of Cohen’s d of .3, using a paired t-test at a 5% alpha level (two-tailed) threshold with 80% statistical power.

3.3. Experimental design

Through a retrospective view, a correlational design will be used to assess the relationship between rejection and childhood abuse towards Avoidant Personality Disorders under two different cultural backgrounds. Participants involved in this study will be finishing the three measures at their own home in front of computers. Participants in the experimental group will be assigned to 3 measures that test whether they are avoidant, their extent of receiving rejection and childhood abuse during childhood and adolescence, and their degree of positivity/negativity of childhood memories. The control group will not be assigned to any of these measures.

3.4. Procedures

Participants will complete three measures in total at three consecutive time intervals, and the experiment duration lasts for 114 minutes (1.9 hours), including the 2-hour rests that happens at the end of Time 1 and Time 2. One hundred and seventy-eight adult participants (89 males and 89 females, mean age = 21.56 years) growing under a Chinese parenting background, and one hundred and seventy-eight adult participants (89 males and 89 females, mean age = 20.95 years) growing under an American parenting background will be recruited for participation. The participants growing under the Chinese background will be randomly selected from a university in Beijing, and the participants growing under the American background will be randomly selected from a university in Washington. An email will be sent to the students at the university, and they are required to answer a small survey that asks them about their age, their email address and briefly demonstrates the aims of the present study and guaranteed participant anonymity. The survey will also ask whether the person had experiences signs of rejection and childhood abuse during childhood in their families, which consists of three choices: yes, no, and I do not remember. Participants will be automatically excluded if they responded that they picked the third choice. Once these participants passed the pre-determined selection criteria, a link to the 2 questionnaires will be sent through their email. Participants can determine when they prefer to participate in the study if the time is controlled within 114 minutes, and they did not pass the due date of the data collection (2 months after). Participants cannot stop and quit once the first survey is being opened. During Time 1, participants are first asked about the culture they grew up in from the two choices: American or Chinese. Then participants viewed, and answer questions based on the Five Factor Avoidant Assessment scale questions answered based on a five-point scale ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree [4]. The scale is to determine whether one fits the description of being Avoidant. Participants will receive a note that allows them to rest for 2 hours on their screen once they’ve finished the Five Factor Avoidant Assessment scale. The rest is to make sure they do not get influenced by the previous questionnaire once they’ve begin answering the second questionnaire. Next, participants will click on the link to the second questionnaire: The Childhood Experience Questionnaire-Revised (CEQ-R) interview. Participants first must answer 8 questions within the positive experiences’ domain, related to the participant’s youth achievements; another 10 questions follow up that asks about the positive interpersonal relationships with others; 10 questions about the participant’s caretaker competencies; 12 questions in total, with 5 questions related to 5 types of childhood abuse and 7 questions related to 7 types of neglect. Again, Participants will receive a note that allows them to rest for 2 hours on their screen once they’ve finished the second questionnaire. Lastly, participants will take out a blank piece of paper or a notebook with plant pages to write short open-ended narratives in between 300-500 words. Participants will rewind about their negative childhood memories in terms of family communications. Their work will then be rated by four raters and be converted into quantitative data through this process (coding).

3.5. Measure 1

In an online survey, before participants begin answering the assessing questions, they are required to input their cultural background from the two options: American or Chinese. Then participants viewed, and answer questions based on the Five Factor Avoidant Assessment scale [4]: 121 items answered based on a five-point scale ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree. Four scales were designed to measure facets of Neuroticism. Participants were first shown with questions designed to access Neuroticism traits, which include questions of Apprehension (“I lived in almost constant fear of making a mistake”), Despair (“At times I am convinced that things will never get better), Mortified (“My fear of embarrassing myself kept me from doing things that I might really enjoy) and Overcome (“I fall to pieces when I feel that I am being watched or evaluated). Participants will then answer questions based on the four scales that assess Extraversion: Social Dread (“I am more comfortable by myself than with others”), Shrinking (“I prefer to be a follower rather than a leader in a group”), Risk Averse (Reversed of “I am willing to try almost anything”), and Joylessness (“My friends would be very surprised if I ever jumped due to joy”). Lastly, participants will make responses according to the scale that asses from openness to experience and agreeableness: Rigidity (“I am afraid to try new things”) and Timorous (“I do not understand how anyone could be jealous of me”). Participant will rate their degree of the agreeableness/disagreeableness on each question. At the end of the questionnaire, the results of each participant will form a percentage based on their Avoidant Personality level (the extent of them to have an Avoidant Personality). However, the results will not be accessible or visible for participants once they had finished the scale, which serves to minimize the probability of how some may exaggerate their negative family communication memories once they are acknowledged for being Avoidant.

3.6. Measure 2

About two hours later after completing the Measure 1 survey of the Five Factor Avoidant Assessment, participants participated in responding to The Childhood Experience Questionnaire-Revised (CEQ-R) interview [5], which is a semi structured interview that questions about the occurrence of positive and negative experiences encountered during three age periods at childhood (0-5, 6-12, 13-17 years). For this study, the age interval of 0-5 is modified into the interval of 5-12, in which the age interval of 6-12 is also combined with 0-5. This is to avoid the likelihood of childhood amnesia [10], which refers to a phenomenon in which most people lack memories from their first 3 to 4 years of childhood [11][12][13]. With the two age intervals combined, a single “childhood” period of 5-12 compared with the “adolescent” period of 13-17 was only included in the following questionnaire. In this study particular, each question will be answered in the form of ratings from 0-4, which identifies as the degree to which these events occurred. Participants first must answer eight questions within the positive experiences’ domain, related to the participant’s youth achievements: academically, athletically, extracurricular activities, leadership roles, work, hobby, household responsibilities, and popularity [11]. Another ten questions follow up that asks about the positive interpersonal relationships with others: including the individual’s mother, father, other adult female relatives, other adult male relatives, other adult females, other adult male, female sibling, male sibling, female friend, and male friend. Finally, there are 10 questions about the participant’s caretaker competencies: female work, male work, female social ability, male social ability, female interests, male interests, close relationships of female, close relationship of male, female good family relationships, and male family good relationships. Participants will then be moving onto the negative childhood experiences domain in terms of family communications. There will be 12 questions in total, with 5 questions related to 5 types of childhood abuse: emotional, verbal, physical, caretaker sexual abuse, and non-caretaker sexual abuse; 7 types of neglect: physical neglect, emotional withdrawal, inconsistent treatments, denial of feelings, lack of real relationships, parentification, and failure to protect by caretakers.

3.7. Measure 3

After the two hours break at the end of Measure 2, participants will begin to write a 300-500 words open-ended narrative about their childhood memories related to negative parental communications. Participants will be given a 2 -sided piece of paper with blank lines on it and will be given instructions on how to make a response. The instructions states: On the lines below, please write a paragraph describing your childhood experiences: What are your relationships with your parents like? Do you have mostly good or mostly bad memories (give a reason for either choice)? Are you rather isolated or had many friends? At the bottom of the line paper are six words, and participants are asked to choose a word from the list that mainly describes their childhood: good, bad, fun, exciting, sad, lonely. They are also required to provide specific examples and justification of why they choose one of the keywords. Each participant’s writing will be transcribed into copies and rated by four people who were not aware of the following participant’s status and any kind of measures. The four raters are graduates that all come from well-known or high-education quality universities and held at least a master’s degree on the field of clinical psychology. There will be a 4-point scale that determines the valence (positive vs. negative) of the story: 0 (absolute positive), 1 (mostly positive), 2 (mixed with positive and negative), 3 (mostly negative), and 4 (absolute negative). The mean of the ratings for each participant will be kept for the story’s valence through finding the average of the response of the four raters’ estimation [3]. The 300-500 words in each narrative acts as a measure to control for the story length and make sure it is not too difficult to code into quantitative.

4. Data Analytic Approach

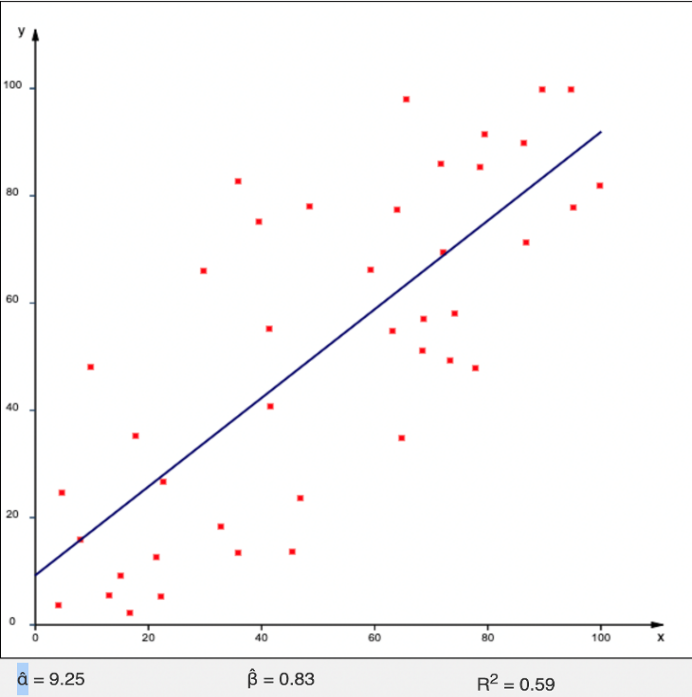

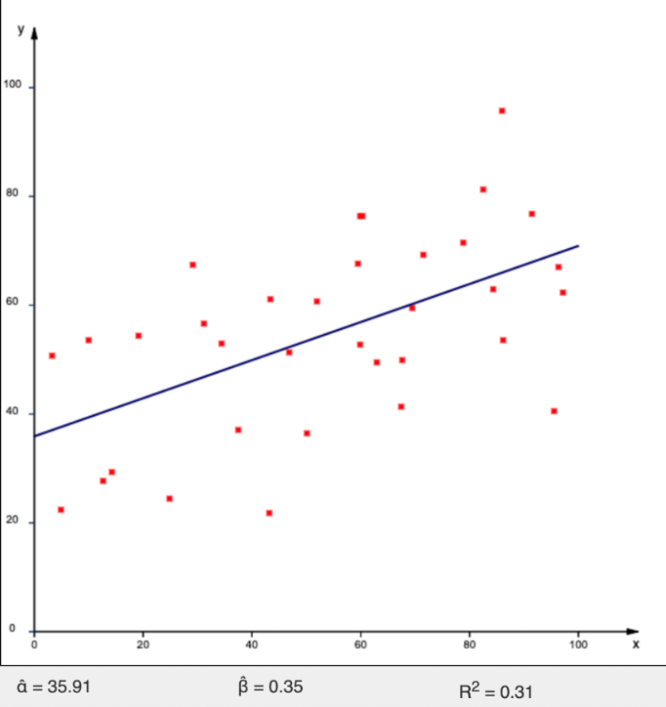

In order to test for the correlation between the extent of rejection and childhood abuse during early-stage family communications and the extent of Avoidant Personality Disorder cross-culturally, we used the Pearson R Correlation to describe the interdependency between data points when estimating the rejection and childhood abuse on Avoidant Personality Disorder. According to the hypothesis, to compare these two variables and its extent, we set the letter R of the correlation under the American parenting culture to be stronger compared to the Chinese parenting culture (the letter R will be quantified with a number, which varies between -1 and +1, while zero means that there is no correlation, where +1 indicated a perfect correlation that is ideal). If the R value is negative, it means that the variables are inversely related. In our prediction, both R values under two cultural backgrounds are positive, suggesting that the higher the extent of rejection and childhood abuse, the higher the extent of being Avoidant. The R value of the Chinese parenting background was set to .31 and the ß value to .4, and both values indicate a moderate and positive correlation since the coefficient lies between +.3 and +.49. It is also predicted that children growing under the American parenting background are more vulnerable to rejection and childhood abuse compared to Chinese children, therefore, the American background correlation will be stronger compared to the Chinese background correlation. This means that the R and ß value will be greater. Thus, the R value is set to .6 and the ß value to .83, which is approximately 2 times stronger than the correlation of the Chinese background. According to the Pearson R Correlation, the higher the absolute value of the coefficient, the stronger the correlation, whereas the American background correlation lies between +.5 and +1, which symbolizes a strong and positive correlation.

5. Results

Descriptive statistics

Aim 1. The work is expected to find rejection and childhood abuse to be correlated with Avoidant Personality Disorder. Specifically, as illustrated in Figure 1, that the higher the degree of rejection and childhood abuse, the higher the level of being Avoidant under both cultures (the culture variable does not influence whether rejection and childhood abuse correlates to Avoidant Personality Disorder).

Aim 2. The work is also expected to find the correlation between rejection and childhood abuse on Avoidant Personality Disorder to be stronger on the children growing under an American parenting background. While the correlation is moderate for the children under a Chinese parenting background.

Figure 1. Scatter plots below shows the illustration of hypothesized effects between rejection and childhood abuse (categorized as negative family communications/memories, x-axis), and the extent how the x-axis contributes to Avoidant Personality Disorder (y-axis). In each panel, each data point represents a response made on the degree of which they’ve encountered rejection and childhood abuse with their diagnosis of Avoidant Personality Disorder (or no diagnosis). The top panel illustrates that we expect children growing under an American parenting background to be more vulnerable and affected by rejection and childhood abuse. The bottom panel illustrates that we expect children growing under a Chinese parenting background would be more resilient towards rejection and childhood abuse.

Figure 1: Hypothesized effects and correlation between rejection and childhood abuse

6. Conclusion

The aim of the present research was to investigate how negative childhood communications in families affect Avoidant Personality Disorder cross-culturally, and the extent to which the present hypothesis is supported by previous theories. It is planned to do construct three measures, in which two out of three measures were in questionaries form. The first questionnaire uses the Five Factor measure of Avoidant Personality, and with participants inputting their cultural background of being American or Chinese, will determine whether the participant holds Avoidant Personality traits. Participants will then be participating in Measure 2, by answering The Childhood Experience Questionnaire-Revised (CEQ-R) interview [5], which is a semi structured interview that questions about the occurrence of positive and negative experiences encountered during three age periods at childhood (0-5, 6-12, 13-17 years, with age intervals of 0-5 and 6-12 are combined, eliminating the 0-4 age interval). Lastly, participants wrote open-ended narratives that were evaluated on their negative/positive degree based on the 4-point scale of 0-4 by raters with a master’s degree in clinical psychology. It is predicted that under both cultures, rejection, and childhood abuse both affect to the development of AVPD. While the children growing under American parenting styles are affected by these family factors to a bigger extent compared to children growing under a Chinese parenting background. The strengths of this research design include: first, the way of accessing each participants’ measures and status is very convenient, such that participants will only need to answer questions accordingly for the correlation between rejection and childhood abuse and Avoidant Personality Disorder to be determined. Second, through a retrospective-questionnaire design, the presence of more than two variables will not cause the results to be difficult to interpret. For instance, even though the cultural variable was added, participants will only need to select the culture they grew up in and this choice will not be easily affected by other factors since it is very direct. Despite the strengths of the design, there are still many limitations. One of the limitations is the nature of the retrospective study, which requires participants to recall the memories about their childhood experiences. This could cause a prone to memory bias or to recall bias, which sometimes an individual either repairs or enhances the recall of a memory piece of altering the content of what one initially remembered. Furthermore, the retrospective study failed to determine the causation of an event and can only determine the association between them. The causation of an event, such as rejection and childhood abuse, is necessary to be known of whether an act is either passive or voluntarily conducted to establish an accurate result. Alternate interpretations suggests that children growing under a Chinese background are more affected by rejection and childhood abuse during family communications. During the past years, school bullying and cyberbullying in China continues. Bullying victimization causes significant impacts on the health of children in their adulthood, and directly affects children’s depression and anxiety [14]. Chinese children also face intense amounts of workload from school and extracurricular activities, while excessive workload has been associated with anxiety and depression [15][16][17]. Along with these two factors, and how most Chinese parenting styles turned out to be Authoritarian, children under this background might face significant pressure, causing them to be more vulnerable of any kinds of rejection they perceive from their environment. Future directions bring up a question of: How can we minimize the occurrence and the symptoms of Avoidant Personality Disorder based on its causes? Past studies have revealed that adults are able to overcome early negative experiences with caregivers, by developing a secure-attachment style. Furthermore, relationships such as Subsequent positive relationships, including psychotherapy, can repair early attachment relationships to an extent that modifies the initial insecure attachment style into a secure one [18]. The main characteristic of a secure attachment is its coherence. Pearson et al. were the first to propose that “earned security” can apply to those with early insecure attachment styles that become secure by later relationships [19]. These findings suggests that negative experiences during childhoods (which also related to Avoidant Personality Disorder) can be remised through earned-secure attachment with partners and closed ones.

To conclude, no matter the culture one grew up in, rejection and childhood abuse during early-stage family communications does affect and indeed contributes to Avoidant Personality Disorder, with only the extent of that impact varies. Negative childhood memories brought by caretakers even at a small age can form the foundation of forming an Avoidant Personality, which impacted an individual’s daily interactions with others and making parts of their lives incompetent and difficult.

References

[1]. Macik, D. (2018). Early maladaptive schemas, parental attitudes and temperament, and the evolution of borderline and avoidant personality features—the search for interdependencies. Psychiatr Psychol Klin, 18, 12-18. doi: 10.15557/PiPK.2018.0002

[2]. Beck AT, Freeman A, Davis DD et al.: Cognitive therapy for personality disorders. Jagiellonian University Press, Cracow 2005.

[3]. Meyer, B., & Carver, Charles. S. (2000). Negative Childhood accounts, sensitivity, and pessimism: A study of Avoidant Personality Disorder features in college students. Department of psychology, University of Miami, 14(3), 233-248

[4]. Lynam, Donald, R., Leohr, A., Miller, Joshua, D., & Widiger, Thomas, A. (2012). A Five-Factor Measure of Avoidant Personality: The FFAvA. 466-474. doi: 10.1080/00223891.2012.677886.

[5]. Zanarini MC, Gunderson JG, Marino MF, Schwartz EO, Frankenburg FR. Childhood experiences of borderline patients. Comp Psychiatry. 1989;30:18–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

[6]. Lampe. L., & Gin. S. Malhi. (2018). Avoidant personality disorder: current insights. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 55-66, doi: 10.2147/ PRBM.S121073

[7]. Howe. C. Lauren., & Dweck. S. Carol. (2016). Changes in Self-Definition Impede Recovery from Rejection. The Society for Personality and Social Psychology, 1-18, doi: 10.1177/0146167215612743.

[8]. Chao, Ruth, K. (1994). Beyond Parental Control and Authoritarian Parenting Style: Understanding Chinese Parenting through the Cultural Notion of Training. University of California, Los Angeles, 65, 1111-1119.

[9]. Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, Albert, G., & Buchner, A. (1996). G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. 39, 175—191.

[10]. Freud, S. (1905/1953). Three essays on the theory of sexuality. In J. Strachey (Trans.Ed.), The standard edition of the complete psychological works of Sigmund Freud (Vol. 7, pp. 135-243). London: Hogarth Press.

[11]. Bauer, P.J., Tasdemir-Ozdes, A., & Larkina, M. (2014). Adults’ reports of their earliest memories: Consistency in events, ages, and narrative characteristics over time. Consciousness and Cognition, 27, 76-88. doi: 10.1016/j.concog.2014.04.008.

[12]. Henri, V., & Henri, C. (1898). Earliest recollections. Popular Science Monthly, 21, 108-115.

[13]. Miles, C. (1893). A study of individual psychology. American Journal of Psychology, 6, 534-558.

[14]. Takizawa, R., Maughan, B., & Arseneault, L. (2014). Adult health outcomes of childhood bullying victimization: Evidence from a five-decade longitudinal British birth cohort. American Journal of Psychiatry, 171(7), 777—784.

[15]. Bachman, L., & Backman, C. (2006). Student perceptions of academic workload in architectural education. Journal of Architectural and Planning Research, 23(4), 271—304.

[16]. Jacobs, S. R., & Dodd, D. K. (2003). Student burnout as a function of personality, social support, and workload. Journal of College Student Development, 44(3), 291—303. https://doi.org/10.1353/csd.2003.0028.

[17]. Parkinson, T. J., Gilling, M., & Suddaby, G. T. (2006). Workload, study methods, and motivation of students within BVSc program. Journal of Veterinary Medical Education, 31(2), 5—24. https://doi.org/10.3138/jvme.33.2.253.

[18]. Roisman, G.L., Padron, E., Sroufe, L.A., & Egeland, B. (2002). Earned-secure attachment status in retrospect and prospect. Child Dev, 73(4), 1204–1219. Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar.

[19]. Pearson, J.L, Cohn, D.A., Cowan, P.A., & Cowan, C.P. (1994). Earned- and continuous-security in adult attachment: Relation to depressive symptomatology and parenting style. Dev and Psychopathol, 6(2), 359–373. doi: 10.1017/S0954579400004636Crossref, Google Scholar.

Cite this article

Zhang,R. (2024). Rejection and Childhood Abuse During Early-Stage Family Communication under Cross-Cultural Background to Avoidant Personality Disorder. Lecture Notes in Education Psychology and Public Media,44,125-133.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the International Conference on Global Politics and Socio-Humanities

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Macik, D. (2018). Early maladaptive schemas, parental attitudes and temperament, and the evolution of borderline and avoidant personality features—the search for interdependencies. Psychiatr Psychol Klin, 18, 12-18. doi: 10.15557/PiPK.2018.0002

[2]. Beck AT, Freeman A, Davis DD et al.: Cognitive therapy for personality disorders. Jagiellonian University Press, Cracow 2005.

[3]. Meyer, B., & Carver, Charles. S. (2000). Negative Childhood accounts, sensitivity, and pessimism: A study of Avoidant Personality Disorder features in college students. Department of psychology, University of Miami, 14(3), 233-248

[4]. Lynam, Donald, R., Leohr, A., Miller, Joshua, D., & Widiger, Thomas, A. (2012). A Five-Factor Measure of Avoidant Personality: The FFAvA. 466-474. doi: 10.1080/00223891.2012.677886.

[5]. Zanarini MC, Gunderson JG, Marino MF, Schwartz EO, Frankenburg FR. Childhood experiences of borderline patients. Comp Psychiatry. 1989;30:18–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

[6]. Lampe. L., & Gin. S. Malhi. (2018). Avoidant personality disorder: current insights. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 55-66, doi: 10.2147/ PRBM.S121073

[7]. Howe. C. Lauren., & Dweck. S. Carol. (2016). Changes in Self-Definition Impede Recovery from Rejection. The Society for Personality and Social Psychology, 1-18, doi: 10.1177/0146167215612743.

[8]. Chao, Ruth, K. (1994). Beyond Parental Control and Authoritarian Parenting Style: Understanding Chinese Parenting through the Cultural Notion of Training. University of California, Los Angeles, 65, 1111-1119.

[9]. Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, Albert, G., & Buchner, A. (1996). G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. 39, 175—191.

[10]. Freud, S. (1905/1953). Three essays on the theory of sexuality. In J. Strachey (Trans.Ed.), The standard edition of the complete psychological works of Sigmund Freud (Vol. 7, pp. 135-243). London: Hogarth Press.

[11]. Bauer, P.J., Tasdemir-Ozdes, A., & Larkina, M. (2014). Adults’ reports of their earliest memories: Consistency in events, ages, and narrative characteristics over time. Consciousness and Cognition, 27, 76-88. doi: 10.1016/j.concog.2014.04.008.

[12]. Henri, V., & Henri, C. (1898). Earliest recollections. Popular Science Monthly, 21, 108-115.

[13]. Miles, C. (1893). A study of individual psychology. American Journal of Psychology, 6, 534-558.

[14]. Takizawa, R., Maughan, B., & Arseneault, L. (2014). Adult health outcomes of childhood bullying victimization: Evidence from a five-decade longitudinal British birth cohort. American Journal of Psychiatry, 171(7), 777—784.

[15]. Bachman, L., & Backman, C. (2006). Student perceptions of academic workload in architectural education. Journal of Architectural and Planning Research, 23(4), 271—304.

[16]. Jacobs, S. R., & Dodd, D. K. (2003). Student burnout as a function of personality, social support, and workload. Journal of College Student Development, 44(3), 291—303. https://doi.org/10.1353/csd.2003.0028.

[17]. Parkinson, T. J., Gilling, M., & Suddaby, G. T. (2006). Workload, study methods, and motivation of students within BVSc program. Journal of Veterinary Medical Education, 31(2), 5—24. https://doi.org/10.3138/jvme.33.2.253.

[18]. Roisman, G.L., Padron, E., Sroufe, L.A., & Egeland, B. (2002). Earned-secure attachment status in retrospect and prospect. Child Dev, 73(4), 1204–1219. Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar.

[19]. Pearson, J.L, Cohn, D.A., Cowan, P.A., & Cowan, C.P. (1994). Earned- and continuous-security in adult attachment: Relation to depressive symptomatology and parenting style. Dev and Psychopathol, 6(2), 359–373. doi: 10.1017/S0954579400004636Crossref, Google Scholar.