1. Introduction

As music education evolves, improvisational accompaniment has become vital for music majors, garnering attention from universities and scholars. However, the complexity of the curriculum often hinders achieving teaching objectives, prompting students to seek further enhancement of their improvisational skills post-graduation. Cultivating harmonic thinking is crucial for improving improvisational proficiency. Traditional harmonic methods fall short in meeting modern musical demands. This paper explores strategies for fostering diverse harmonic thinking in improvisational accompaniment teaching, enhancing students' interdisciplinary practice and musical literacy. Innovative approaches, such as integrating diverse musical styles, adopting compositional principles, and utilizing inner auditory perception, are proposed. Emphasis on practice and reflection aims to develop students' harmonic thinking comprehensively, enhancing their improvisational skills. This endeavor is pivotal for nurturing music educators with innovative prowess.

2. Analysis of the Current State of Improvisational Accompaniment Teaching System

Improvisational accompaniment is a comprehensive artistic form that integrates keyboard performance techniques, knowledge of harmonic theory, expertise in accompaniment texture application, and rich imagination. Proficiency in improvisational accompaniment necessitates a profound musical foundation[1] Moreover, as a compulsory course for music majors, improvisational accompaniment holds a significant position within the professional music education system of higher institutions, with a wealth of excellent research findings and teaching materials accumulated over the years. [2]

Traditionally oriented towards employment prospects, the curriculum of improvisational accompaniment in music education programs primarily aims to cultivate students' abilities in arranging accompaniments for songs in primary and secondary school teaching materials. Although most students grasp the general methods of arranging simple harmonic functions, they often lack understanding in the organization and principles of chord structures, as well as the techniques for expanding tonalities in arrangement. Furthermore, there is a deficiency in improvisational composition and performance skills, making it challenging for them to develop a robust inner auditory perception and diversified harmonic thinking.

In recent years, the author has encountered music majors from diverse academic backgrounds, including music education (normal), music performance, transfer from non-music to music majors, and vocational music education, with varying levels of proficiency in keyboard performance. After extensive review, collection, and study of numerous teaching materials and literature, it becomes apparent that the prevailing teaching system often divides the arranging process into three main components: Firstly, a simple analysis of the song's key, mode, and structure; secondly, arranging harmonic functions for the melody, with harmony as the primary criterion; thirdly, selecting accompaniment textures that match the melody style based on different keyboard performance abilities.

Through evaluation feedback and communication with students, it is evident that a significant portion of students still have vague understandings of chord properties, the sonic effects of chords, and the functional logic between them, despite theoretical explanations and simple demonstrations by teachers regarding major thirds, minor thirds, and altered chords. Consequently, upon entering educational positions, they encounter various difficulties. To achieve better teaching outcomes, diligent students may use song scores for accompaniment practice, while others rely on intuition for chord progression, resulting in improvised accompaniments that do not necessarily match the song's style. Consequently, innovative and personalized harmonic function schemes are lacking.

Although the author's expertise lies in traditional compositional techniques and theories, they frequently engage with contemporary popular music works alongside their teaching responsibilities. In doing so, they have encountered numerous outstanding compositions. Through the process of "deconstructing" and rearranging these works, the author has gained a deeper appreciation for the significant enhancement in overall quality that meticulous harmonic arrangements can bring to a composition. It is observed that for many music majors, their level of aural perception or inner auditory acuity may make it challenging to grasp the harmonic progressions within a song upon initial listening. However, when instructed to consistently practice playing chords or pre-arranged harmonic songs for a period, some students pleasantly surprise as their understanding of harmonic arrangement gradually clarifies, and their arranging logic becomes more rigorous. This observation prompts the author's consideration that to address issues in students' harmonic thinking, it is imperative to broaden their musical horizons. Introducing students to a diverse range of musical genres enables them to learn the harmonic arrangement concepts embedded in exceptional works. Moreover, drawing from the practice methods of popular and jazz keyboard improvisation can not only enrich teaching content but also yield favorable teaching outcomes.

3. Cultivating Diversified Harmonic Thinking in Improvisational Accompaniment

3.1. The cultivation of diversified harmonic thinking ability

The cultivation of harmonic thinking ability entails the capacity to perceive and comprehend various harmonic sound structures. This encompasses not only the discernment of chord properties but also the ability to assess the functional tendencies within harmonic progressions. Such proficiency necessitates prolonged engagement in arranging and performance practices. Upon mastering these skills, the flexible application of phrase structures from musical compositions to improvisational accompaniment practices is essential for achieving favorable auditory outcomes. Evidently, this is an outcome of collaborative efforts across multiple academic disciplines. Therefore, in pedagogy, the primary task is to enable students to differentiate between appropriate and inappropriate melodic and harmonic pairings. Without the ability to discern the correctness of harmonic arrangements, students cannot develop the capability to arrange harmonies.[3]

3.2. The cultivation of diversified harmonic thinking ability

The cultivation of students' harmonic thinking ability is a long-term and arduous task, requiring both an understanding of the general principles of musical development within compositions and the capability to swiftly select the correct harmonic functions in a manner akin to "muscle memory."[4] Moreover, due to the unique nature of improvisational accompaniment as an art form, it is common for different arrangements to be devised by the same individual for the same piece, posing challenges in teaching. It is imperative to remind students that "improvisation" does not imply haphazard or arbitrary performance, but rather demands rigorous logic and intricate conception. While arrangements may vary, the conceptual framework must remain clear and accurate.

Drawing upon teaching examples, this discussion will delve into methods for enhancing students' harmonic thinking ability, encompassing skills such as chord selection, arrangement within keys, arrangement outside keys, and modulation techniques.

3.2.1. The capacity for harmonic selection

Songs, as relatively short and comparatively simple musical forms, typically belong to the realm of traditional tonal music, primarily emphasizing harmony to facilitate memorization and comprehension. Although each individual's arrangement of the same song may vary significantly, harmony remains its primary characteristic. Therefore, students must possess a certain level of aural perception and fundamental knowledge of harmonic theory. Through training, they should be able to judge the appropriateness and correctness of harmonies both theoretically and perceptually.

During the initial stages of learning, when arranging harmonic functions for the melody, it is preferable to use a single chord that encompasses as many melody notes as possible. This method yields harmonious harmonic function schemes with strong auditory coherence. However, it may result in fixed harmonic rhythms and a relatively uniform harmonic palette. Particularly when arranging for songs with complex and varied melodic lines, it becomes challenging to achieve the aforementioned effects. In such cases, it is necessary to extract the essential notes from the melody, such as the middle notes of subdivided rhythms, long-duration notes of dotted rhythms, or notes occupying strong beats or positions. Simultaneously, it is essential to exclude passing tones, auxiliary tones, anticipations, and appoggiaturas, and then arrange the remaining melody notes to achieve optimal auditory outcomes.

Subsequently, students can begin with harmonic rhythms, guiding them to design appropriate harmonic rhythms, gradually diversifying and recombining the harmonic rhythms originally consisting of one or two chords per measure. Through this progressive arrangement training approach, students' harmonic thinking abilities can be effectively expanded.

The aforementioned approach is commonly employed in traditional improvisational accompaniment courses. Through systematic and scientific training, students can experience the acoustic effects of harmonic progression. However, due to the relatively weak theoretical foundation of some students and their lack of innovative deductive abilities, there is a tendency to repetitively use familiar chord arrangement schemes. Therefore, we can also consider adopting training methods from popular keyboard harmonization.

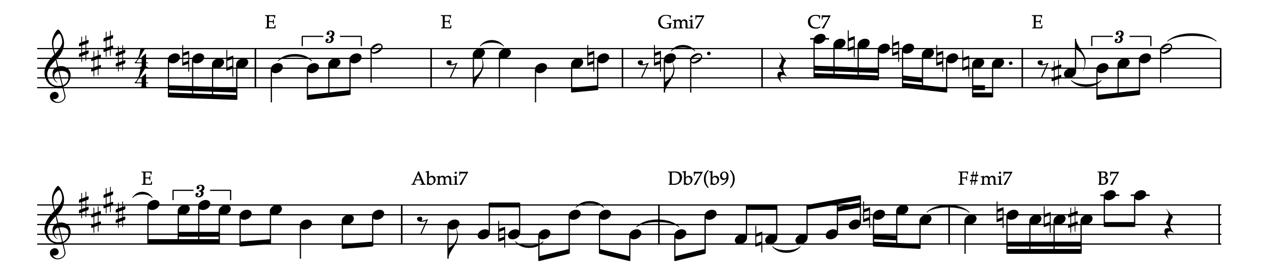

Teachers can select some widely sung and distinctive popular music pieces or relatively simple jazz standards to complement our teaching. For instance, Figure 1 is an excerpt from the first nine bars of the jazz classic "Out of Nowhere" composed by Charlie Parker, where the harmonic functions have already been arranged. Students are encouraged to repeatedly perform these well-structured and accurate harmonic progressions, selecting suitable accompaniment textures, and thereby perceive the harmonic colors. Subsequently, teachers can provide theoretical explanations, thus creating a cyclic learning process. Through this iterative approach, students' inner auditory perception and aesthetic standards will undergo substantial enhancement.

Figure 1: From Charlie Parker, "Out of Nowhere," Bars 1-9.

3.2.2. Harmonic Arrangement within Keys

Throughout the centuries-long development of music, there has been a significant period of "collective creation," during which the aesthetic value of music has largely remained within a relatively stable dimension. Nowadays, with the progress of society and the refinement of people's aesthetic tastes, new explorations have emerged since the late Romantic period, breaking free from tonal constraints, and various novel and unique musical forms have proliferated. However, for students who are still in the foundational stage of learning and training, the ability to arrange chords within keys remains crucial.

Chords composed of the seven basic tones within a key encompass various types of triads and seventh chords, satisfying initial arrangement needs. In the process of selecting harmonic arrangement schemes, rapid recognition of the functional attributes and application rules of chords is necessary.[5] It is often recommended that students classify chords according to their functionality, as shown in the table below. Extensive research findings on the characteristics and tendencies of tonic, subdominant, and dominant function chords are readily available for study, thus further elaboration is omitted here.

Table 1: Key-based Chords

Functional Attributes | Main Function | Subordinate Function | Dominant Function |

Corresponding Chords | I,VI | VI,IV,II | V,III,VII |

According to the table 1, the author concludes from teaching experience that when composing, the tonic chords I and VI are commonly used as primary functional chords, while the subdominant chords VI, IV, and II are frequently employed as subordinate functional chords, and the dominant chords V, III, and VII are typical for dominant functional chords. Although some chords have dual functional attributes, certain choices can be made based on their frequency of use. For instance, among the chords within the key, the III chord often functions as a subdominant chord. On the other hand, the VI chord's usage is more versatile; it can serve as a substitute for the tonic chord, adding different harmonic colors to the beginnings of two repeated phrase relationships. Additionally, it can function as a subdominant chord to propel musical development due to its two common tones with the tonic chord, playing a transitional role between stability and instability. Furthermore, it can be used at cadential points, typically appearing in the form of V(7) to VI, not only expanding the structure of the phrase but also serving as a starting point for interludes, facilitating a more natural transition between two musical sections.

To efficiently conduct logical harmonic arrangement, firstly, one should understand the general rules of musical development, namely stability-unstableness-increased unstableness-stability (tonic-subdominant-dominant-tonic). Secondly, it's essential to remember the functional properties of chords, using the functional progression direction as a guiding principle. During this process, chords within the same functional group can be interchangeable to avoid consecutive occurrences of similar chords. Simultaneously, students should possess a certain level of proficiency in musical analysis, accurately determining the tonality of a piece, and being able to precisely divide phrases and sections. Based on establishing the harmonic functions of each phrase and section's "head" and "tail," crucial chord schemes for half cadences, cadences, cadence interruptions, and supplemental cadences can be further determined. Subsequently, harmonic fillings for the development of the middle section can be added, resulting in higher efficiency in arrangement.

It is evident that there are multiple options for the arrangement of chords within the key. As long as students understand the functional properties of chords and arrange them according to the general rules of musical development, they can achieve effective harmonic arrangements. Especially in the process of musical development, there is no need to strictly adhere to predetermined chord schemes for improvisation. Creativity can be fully unleashed, embodying the true essence of "improvisation." However, given the diverse styles and themes of songs, which often involve various conflicts and emotional changes, relying solely on chords within the key for arrangement may lack color and become monotonous over time. Therefore, after mastering the above methods proficiently, students can further enrich the expressiveness of music by incorporating chords outside the key for arrangement.

3.2.3. The ability to arrange chords outside the key

The rational use of non-diatonic chords can significantly enhance the tonal richness of accompaniment music. Among the non-diatonic chords commonly used in improvisational accompaniment are the secondary dominant and secondary subdominant chords. However, the ability to swiftly complete arrangements often relies on "inertia," hence when guiding students, training should be supplemented with clear short-term objectives to enable proficient application of non-diatonic chords in arrangement. Firstly, it is essential to determine the positions for using non-diatonic chords. When selecting these positions, factors to consider primarily include whether they can highlight contrasts between repeated musical phrases, serve as effective fillers during relatively static melodies, and provide good transitional support at terminations or half-cadences.

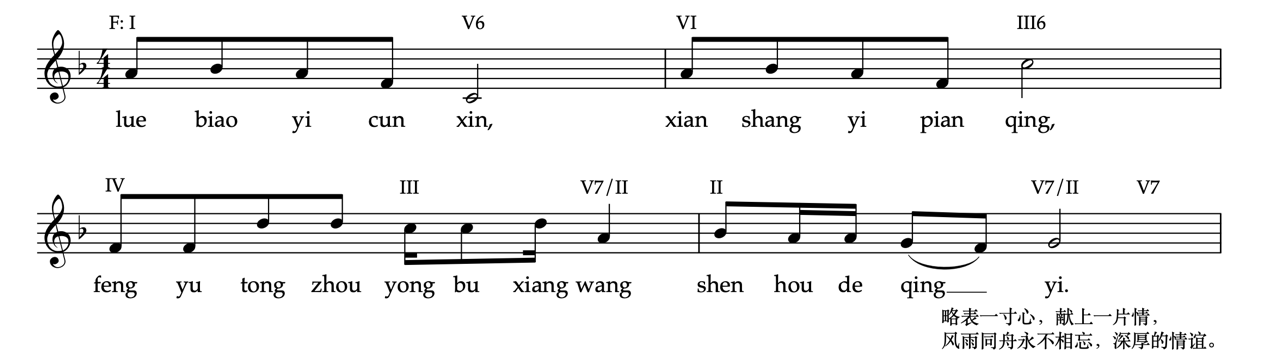

For example, in the excerpt from the song "Walking with Hope" by Shen Yingjie (lyrics) and Gong Yaonian (music) shown in Figure 2, the third beat of the fourth measure marks a half-cadence. The conventional approach would be to use the dominant chord (V). However, by preceding the dominant chord with a secondary dominant chord, a sequence of minor and major triads (temporary subdominant and temporary tonic chords) is formed within this measure. This not only diversifies the nature and functional progression of the chords but also renders the subsequent resolution to the dominant chord more natural due to the progression of inner voices by semitone.

Figure 2: From Shen Yingjie (Lyrics), Gong Yaonian (Music). "Hope to Walk with You."

Furthermore, the major and minor subdominant chords mainly consist of major and minor seventh chords, while the major and minor subdominant leading chords primarily involve diminished and diminished minor seventh chords. The two differ in tonal color, with the former being brighter and tending more toward resolution, thus creating a stronger sense of anticipation in auditory perception.

The latter, on the other hand, exudes more tension due to its compressed internal structure, resulting in a stronger sense of expansion and extension upon resolution. In the last beat of the third measure in the figure above, the melody pauses for a relatively long duration. After incorporating the minor subdominant chord, which is preceded and followed by minor third chords, the raised fourth note (#F) in the minor subdominant chord stands out. Furthermore, this note has an inherent tendency to gravitate towards the temporary tonic G, leading to a satisfying resolution.

As a result, the fluctuation in auditory perception becomes more pronounced. The choice of this arrangement serves two purposes: first, to contrast with the previous sections of the melody, creating a development in the harmonic layer; second, to emphasize the logical relationship conveyed in the lyrics, highlighting the logical emphasis in the lyrics, namely, "yong bu xiang wang (never forget)," as a tribute to the "shen hou de qing yi (profound friendship)" that should not be forgotten. Therefore, to effectively enrich the content of improvisational accompaniment using non-diatonic chords, it is necessary to define the objectives of arrangement based on the analysis of the lyrics and melody structure of the song. After students become proficient in using diatonic chords, they can practice arranging non-diatonic chords based on the target chords they need to resolve to at key points in the song.

It is essential to emphasize the importance of "listening" once again: after determining the arrangement plan, students should constantly use their ears to judge whether the harmonic progression scheme is correct and whether it meets the expressive needs of the music content.

3.2.4. The ability to arrange using tonal alternation.

The application of tonal alternation techniques in arrangement and the use of non-diatonic chords share similarities in purpose, both aiming to enrich the color and depth of harmony. In improvisational accompaniment, the tonal alternation technique involves relationships between tonic and relative keys, parallel major and minor keys, and closely related keys. Since song melodies typically do not involve modulation or the presence of non-diatonic tones, this increases the difficulty for students in selecting non-diatonic chords during arrangement. The following example illustrates the practical approach to such arrangement techniques.

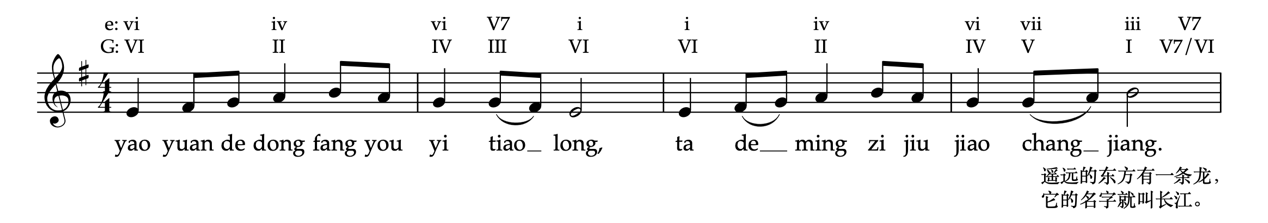

Figure 3: From Hou Dejian (Lyrics and Music). "Descendants of the Dragon."

The above Figure 3 is excerpted from the song "The Descendant of the Dragon," composed and written by Hou Dejian. It is a segment of a song in the key of E minor, where the melody does not include non-diatonic tones. Two harmonic arrangement schemes are presented above the melody: the first line is marked within the tonal environment of E minor, while the second line is marked within the tonal environment of G major.

Upon observing the first two measures, regardless of the tonal environment, the functional nature of the chords remains the same. Thus, the harmonic progression for these two measures follows the pattern of "tonic-subdominant-tonic." Subsequently, in the fourth measure, the technique of tonal alternation is applied. Here, borrowing from the parallel major key of E minor, which is G major, the progression "IV-V-I" is employed, a commonly used harmonic progression for cadences.

The consecutive major triads create a positive and bright sound, serving to propel the development of musical emotions. While the appearance of the cadence at this point would typically imply a sense of resolution, as it is only the end of a phrase, there is no prolonged stay on the tonic chord (I). Instead, it promptly returns to the tonic through the use of the subdominant chord borrowed from the parallel minor key of G major, which is E minor. This arrangement not only facilitates the transition back to the tonic but also lays the groundwork for a modulation to the key of G major in the subsequent chorus section.

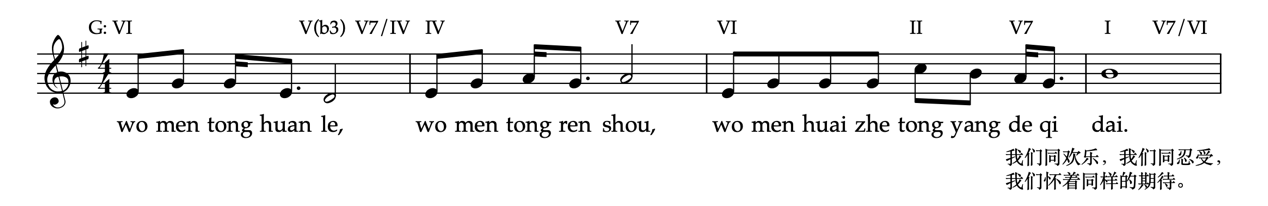

Figure 4: From Chen Zhe, Liu Xiaolin, Wang Jian, Guo Feng, Sun Ming (Lyrics), Guo Feng (Music). "Let the World Be Full of Love."

The figure 4 is excerpted from the song "Let the World Be Filled with Love" written by Chen Zhe, Liu Xiaolin, Wang Jian, Guo Feng, and Sun Ming, with music composed by Guo Feng. In the second measure of this song, the harmonic progression also employs the technique of modal interchange. The progression "b3V (II/IV)-V7/IV-IV" essentially borrows the subdominant termination harmonic progression of the key of C major, moving in the direction of the subdominant from the main key of G major, which is the "II-V7-I" progression of C major. However, due to its short duration, it is less stable and does not create a sense of termination or modulation.

Such harmonic techniques are commonly used in the development of music and are particularly prevalent in jazz music. The temporary tonic chords resolved by this harmonic progression are typically the VI, IV, and II chords of the main key, making it an advanced supplementary version of the subdominant chord. This type of harmonic progression is characterized by strong flow between voices, noticeable alternations in chord color and harmonic progression strength, and effective filling of melodic gaps, making it suitable for use before the target subdominant chord in the development and evolution of the main theme melody, enhancing the driving force of music development and continually surprising and refreshing listeners.

Although there are numerous types of modal interchange harmonic techniques, through the analysis of the examples above, we can still identify some patterns and training strategies for harmonic arrangement. Firstly, both modal interchange and the use of borrowed chords require a clear understanding of the target chord (i.e., the temporary tonic chord). To achieve this, students should first strengthen their proficiency in playing the harmonic connections at each tonal termination, enabling their hands to keep up with changes in harmonic arrangement. Secondly, since this harmonic arrangement technique is often used in the development of music, indicating its strong dynamic nature, students should enhance their ability to quickly identify harmonic functions and analyze the structure of musical works during their regular studies, enabling them to accurately locate positions suitable for applying modal interchange harmonic arrangement techniques and thereby creating brilliant harmonic arrangement solutions to assist in the interpretation of songs.

4. Conclusion

As an essential skill for music majors, improvisation is typically applied to smaller musical genres such as songs. While improvised accompaniment may not rival the intricate design of notated accompaniment, its versatile style of arrangement and distinct personal flair often captivate audiences. However, one of the crucial factors contributing to its diverse effects is harmony, which is often a challenging aspect for students to grasp. Therefore, in teaching, it is important to use excellent arrangement schemes or works as a foundation to enhance students' ability to judge harmonic functions and their level of musical aestheticism.

At the same time, when teachers modify arrangement schemes, they should explain the reasons behind the changes to students, enabling them to gradually develop diverse harmonic thinking and eventually form their own conceptual approaches and personal styles. The above reflections are just some of the insights gained from my teaching experience. I hope that through the analysis and writing of this article, I can further contribute to the classroom. Moreover, I also hope to provide some teaching references to my colleagues and contribute my modest efforts to the cultivation of music majors with excellent professional qualities.

References

[1]. Rui, Q. Fusion and conception: on the cultivation of harmonic thinking ability in sight-singing and ear training teaching. Shanghai Normal University Master's Thesis, 2016(05):1.

[2]. Tao, L. Analysis of the Current Situation of Piano Accompaniment Course Teaching for Non-Piano Major Students in Vocational Colleges. Art Evaluation, 2019(05):118-120.

[3]. Tian, K. How to Solve the Problem of Harmony Thinking of College Students Using the Teaching Mode of Popular Keyboard Improvisation Accompaniment. Dàwǔtái (The Big Stage), 2011(06):196-197.

[4]. Yu, X. Experimental Report on Basic Teaching Method of Piano Improvisation Accompaniment: An Empirical Study Based on the Cultivation of Improvisation Accompaniment Ability in Piano Teaching. Zhōngguó Yīnyuè (Chinese Music), 2009(02):230-232+242.

[5]. Ni, G. Theory and Practice of Piano Improvisation Accompaniment. Suzhou University Press, 2020.

Cite this article

Han,X.;Xu,M. (2024). Cultivating Diverse Harmonic Thinking in Improvisational Accompaniment: Strategies and Case Studies Exploration. Lecture Notes in Education Psychology and Public Media,51,197-204.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Social Psychology and Humanity Studies

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Rui, Q. Fusion and conception: on the cultivation of harmonic thinking ability in sight-singing and ear training teaching. Shanghai Normal University Master's Thesis, 2016(05):1.

[2]. Tao, L. Analysis of the Current Situation of Piano Accompaniment Course Teaching for Non-Piano Major Students in Vocational Colleges. Art Evaluation, 2019(05):118-120.

[3]. Tian, K. How to Solve the Problem of Harmony Thinking of College Students Using the Teaching Mode of Popular Keyboard Improvisation Accompaniment. Dàwǔtái (The Big Stage), 2011(06):196-197.

[4]. Yu, X. Experimental Report on Basic Teaching Method of Piano Improvisation Accompaniment: An Empirical Study Based on the Cultivation of Improvisation Accompaniment Ability in Piano Teaching. Zhōngguó Yīnyuè (Chinese Music), 2009(02):230-232+242.

[5]. Ni, G. Theory and Practice of Piano Improvisation Accompaniment. Suzhou University Press, 2020.