1. Introduction

Social psychologists have demonstrated a keen interest in exploring the psychological factors contributing to social inequality. Significant attention has been directed towards the issue of unfair treatment within workplace settings, particularly regarding the debate over the relative impacts of several factors. Among all, research has increasingly centered on the role of gender. In this paper, the presented study aims to examine how subtle gender differences in communication skills may affect employee job satisfaction in the workplace.

Gender disparities in communication skills have been demonstrated in previous literatures. Female physicians typically demonstrate higher levels of empathy and utilize more positive language when engaging with patients [1]. Similarly, the study carried out by Holm and Aspegren [2] indicated that female students often exhibit superior communication competencies in training courses in communication skills. These gender differences in communication skilled performance within medical contexts lend support to the idea that females may possess heightened linguistic proficiency for internal communication. This may be explained by Guadagno and Cialdini’s [3] position that these early differences in communication style stem from gender-based expectations regarding social roles. However, some researchers contend that these differences can be attributed to social role theory, which posits that behavioral discrepancies between genders often arise from the societal roles assigned to men and women across various cultures [4]. Therefore, analyses of gender disparities in communication styles should incorporate socio-environmental factors for a comprehensive understanding.

Another aspect examined in this study is job satisfaction. Job satisfaction defined by H. M. Weiss [5], refers to an individual's overall evaluative judgment regarding their job. In the study carried out by Muskat and Reitsamer [6] on Generation Y (Gen-Y) employees, gender differences were observed in job satisfaction and quality of work life, with variations influenced by perceived job security, appreciation, and decision-making opportunities. This gender paradox in job satisfaction can be partially explained by Eagly's [7] gender role social expectation theory, which emphasizes how societal norms and expectations shape and perpetuate traditional gender roles. Such social roles may manifest in the workplace, with women and men attributing different values to intrinsic and extrinsic rewards, consequently affecting their levels of job satisfaction [8]. However, diverse perspectives persist and continue to be investigated. For instance, studies examining the gender paradox in job satisfaction across different regions yield varying outcomes. A comparative analysis by Hauret and Williams [9] demonstrates this uncertainty. They found that women reported higher job satisfaction levels than men using the European Household Community Panel (ECHP) data. However, an International Social Survey Program (ISSP) study using an ordered Probit model in 1997 found no significant gender difference in job satisfaction. This highlights the complexity of understanding gender differences in job satisfaction and underscores the need for further research considering contextual and methodological factors.

There is also a growing amount of research on communication skill levels and job satisfaction. Given the observed gender disparities in both communication skill levels and job satisfaction, it becomes pertinent to undertake a more specific exploration of gender differences in the workplace. This study employs a quantitative methodology with Chinese participants to examine both communication skill levels and job satisfaction. The hypothesis proposed is H0: "With similar levels of communication skills, female employees will exhibit higher job satisfaction than male employees."

2. Method

2.1. Participants

A total of 136 participants were recruited through an online questionnaire performed by the WJX platform. Of these, 40 participants were excluded due to their responses to each statement points to the same degree. The final sample (N = 96) ranged in age from 20 to 58 years (Mage = 35.2, SDage = 9.21; 60.4% female). All participants had work experience and had an average of 12.1 years of experience.

2.2. Ethical Statement

Informed consent and debrief forms were designed for participants' engagement. Before enrolment, all participants provided signed informed consent which included a comprehensive information sheet outlining the questionnaire’s purpose and emphasizing the voluntary nature of participation. Participants were assured that their responses would be presented anonymously and that they had the right to withdraw and quit participation at any stage.

2.3. Materials

An online survey was comprised of 3 parts: an introduction, demographic questions, and 2 different scales measuring workplace communication skills and job satisfaction respectively. The introduction outlined the purpose of the study. Demographic questions were set to gather basic participant information, including age, gender, and years of working experience. The survey comprised 2 types of items, consisting of 30 statements drawn from designed and previously employed scales. To assess the workplace communication skill level, a self-designed scale was developed through a literature review and personal comprehension of communication skills used in the workplace. After subsequent refinement, the final scale consisted of 10 items that cover communication skills utilized in the workplace with co-workers, leaders, and clients. Cronbach’s alpha .92 indicated high internal consistency among the items, suggesting they were interrelated and reliably measured the workplace communication skill levels. Additionally, further validity checks were conducted and showed it has high criterion validity and convergent validity. The remaining 20 items were adopted from the Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire Short Form [5], aimed at measuring employees’ general job satisfaction via intrinsic and extrinsic factors, such as satisfaction with the work itself, relationships with colleagues, and opportunities for advancement. A 5-point Likert Scale was employed for both measurement scales (1 = Strongly Disagree, 3 = Somewhat, 5 = Strongly Agree) to ensure uniformity in participants’ responses. An open-ended space was set at the end of the survey for participants to give suggestions and ask questions.

2.4. Procedure

Participants were directed from the disseminated link to a WJX survey. Following signing the informed consent, each participant was required to complete the survey with honesty and offered an optional opportunity to give feedback and suggestions.

3. Results

Prior to analysis, data from 40 participants claimed above were removed. Participants’ ratings for each statement were examined using IBM SPSS Statistics [10] and R (V4.3.2, https://www.r-project.org/) through RStudio [11] for reverse coding, basic calculations, and cartography.

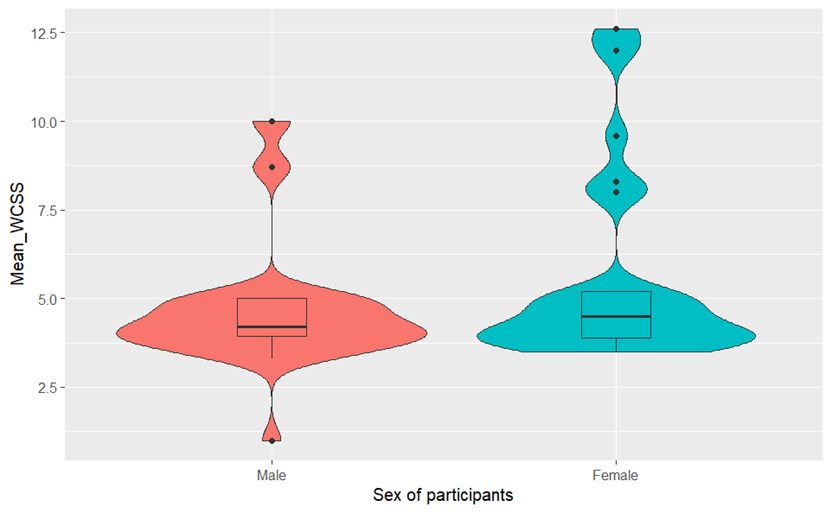

Figure 1: Violin-box plot showing mean WCSS score of different genders: Male (left) and Female (right).

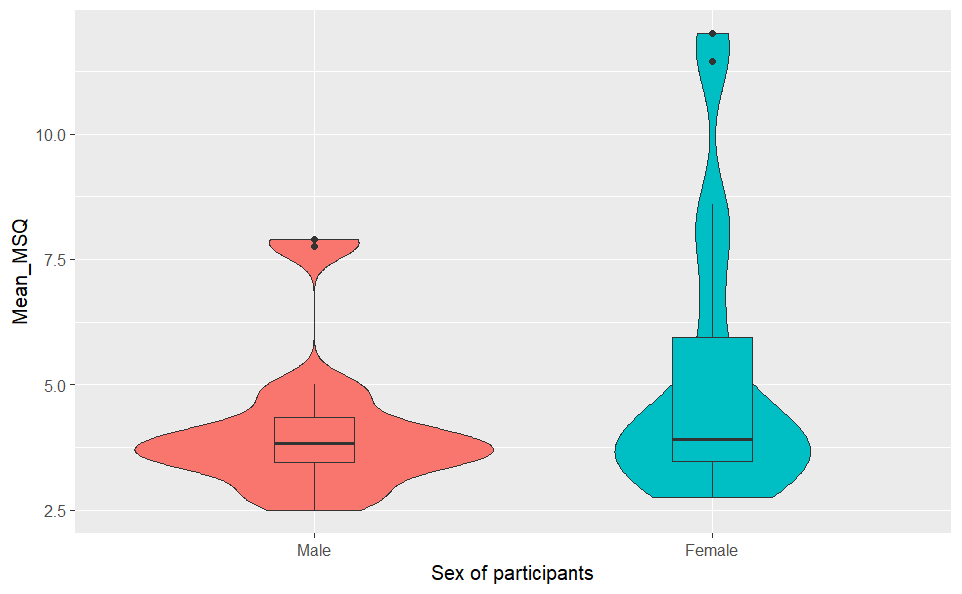

Figure 2: Violin-box plot showing mean MSQ score of different genders: Male (left) and Female (right).

The distribution of the mean scores of the scales by gender is shown in Figure 1 and Figure 2. From the results of the WCSS data analysis, female participants (M = 5.66, SD = 1.79) shown average higher communication skill level than male participants (M = 4.69, SD = 2.76), t(94) = -1.91, p = .06, 95% CI of the difference = [-2.65, 4.59], d = .44. The results indicate that female participants, on average, have higher communication skill levels compared to male participants, with a moderate effect size. Female participants (M = 5.18, SD = 1.42) also showed higher job satisfaction than male participants (M = 4.16, SD = 2.72), t(94) = -2.14, p = .04, 95% CI of the difference = [-1.88, 3.92], d = .50. there is a statistically significant difference in job satisfaction levels between female and male participants, and the effect size suggests a moderate difference in magnitude. With consideration of all the t-test results, it can be inferred that there is a significant gender disparity in the impact of communication skills on job satisfaction, with female participants reporting higher levels of job satisfaction compared to male participants.

To further confirm the results, correlation analysis was conducted, and the results were presented in Table 1.

Table 1: Results of Means, SDs, and Correlation among variables (N = 96).

Variables | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

Gender | 1.60 | .49 | |||||

Age | 35.2 | 9.21 | -.15 | ||||

Work experience | 12.1 | 9.61 | -.18 | .97** | |||

WCSS | 4.16 | .69 | -.05 | .23* | .22* | (.96) | |

MSQ | 3.74 | .61 | -.01 | -.13 | -.12 | .26** | (.96) |

Note: Cronbach’s alphas for each scale are listed in brackets on the diagonal. * p < .05, ** p < .01

The correlation analysis revealed a strong and statistically significant relationship between WCSS and MSQ (r = .26, p < .01), providing strong evidence for the presence of a meaningful and reliable correlation and revealing high criterion validity which refers to how well WCSS corresponds to job satisfaction as an outcome.

4. Discussion

The results reported are in line with the hypothesis and reveal that female employees have relatively higher communication skill levels and job satisfaction compared to male employees. It also suggested that, under similar communication skill levels, female employees also showed higher job satisfaction.

Firstly, our study findings are consistent with existing literature highlighting gender disparities in communication abilities. Consistent with prior research [12], female participants in the study demonstrated significantly higher levels of communication skills. This observation may be attributed to socialization processes and gender role expectations [13] which shape how individuals develop and utilize communication skills in professional contexts. The difference in communication between men and women can also be understood through the lens of differing communication purposes. Research suggests that women often use communication to strengthen social connections and foster relationships, whereas men tend to use language to assert control and achieve tangible outcomes [14]. This inherent difference in communication goals could contribute to disparities in perceived communication effectiveness between genders within workplace settings.

Secondly, the higher job satisfaction observed among female employees, even when accounting for communication skill levels, underscores the intricate relationship between gender dynamics and workplace contentment. These findings are consistent with prior research [6] which suggests that factors like organizational intimacy and trust among colleagues may impact job satisfaction differently for men and women. Another potential explanation for the gender differences in job satisfaction could be linked to the concept of the reference group [9]. This concept posits that relative income, rather than just absolute income, plays a crucial role in determining job satisfaction. In diverse workplace environments where the composition of men and women varies, different treatment and expectations based on gender may contribute to disparities in job satisfaction. Job satisfaction, being multifaceted and influenced by various factors, can be shaped by the social environment within which individuals operate. In workplaces characterized by differing proportions of men and women, varying treatment and expectations based on gender norms may indeed contribute to observed gender differences in job satisfaction levels. Understanding these complex dynamics is essential for addressing gender disparities and promoting equitable workplace environments.

The substantial gender disparity in job satisfaction, especially when considering similar levels of communication skills, emphasizes the necessity for gender-sensitive strategies to enhance workplace satisfaction and promote equitable opportunities. Gender stereotypes and societal expectations likely influence individuals' perceptions of job satisfaction and career fulfilment, contributing to these observed differences. To address these disparities effectively, future research should delve deeper into the underlying mechanisms at play. Exploring additional factors such as organizational culture, leadership styles, and career development opportunities could yield a more comprehensive understanding of why female employees tend to report higher job satisfaction. By examining these contextual elements, researchers can identify specific areas for intervention aimed at fostering gender equity in the workplace. Interventions targeting communication effectiveness and job satisfaction should be tailored to address gender-specific needs and challenges. Implementing strategies that acknowledge and accommodate diverse communication styles and preferences can contribute to a more inclusive and supportive work environment for all employees, regardless of gender. By adopting proactive and nuanced approaches, organizations can strive towards greater gender equality and overall employee satisfaction.

5. Conclusion

In conclusion, the study emphasizes the critical importance of recognizing and addressing gender dynamics in the contexts of communication skills and job satisfaction. By acknowledging and actively mitigating these disparities, organizations can foster more inclusive and supportive environments that enhance the well-being and professional development of all employees, irrespective of gender. Acknowledging gender differences in communication styles and job satisfaction allows organizations to implement strategies that accommodate diverse needs and preferences. This inclusive approach not only promotes equity within the workplace but also contributes to a more positive and fulfilling work environment for employees at all levels.

References

[1]. Bylund, CL, Makoul G. (2024). Empathic communication and gender in the physician–patient encounter. Patient Education and Counseling. 8, 7–16.

[2]. Holm, A. (1999). Pedagogical methods and affect tolerance in medical students. Medical Education.,33(1),14–8.

[3]. Guadagno RE, Cialdini RB. (2002) Online persuasion: An examination of gender differences in computer-mediated interpersonal influence. Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice. Mar;6(1),38–51.

[4]. Ecke,s T, Trautner HM,(2012). editors. Developmental Social Psychology of Gender: An Integrative Framework. In: The Developmental Social Psychology of Gender [Internet]. 0 ed. Psychology Press; 17–46.

[5]. Weis,s DJ, Dawis RV, England GW. (1967) Manual for the Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire. Minnesota Studies in Vocational Rehabilitation.;22,120–120.

[6]. Muska,t B, Reitsamer, BF. (2019) Quality of work life and Generation Y: How gender and organizational type moderate job satisfaction. Personnel Review.49(1),265–83.

[7]. Eagly, AH.( 1987).Reporting sex differences. American Psychologist. Jul;42(7),756–7.

[8]. Doering L, Thébaud S. (2017).The Effects of Gendered Occupational Roles on Men’s and Women’s Workplace Authority: Evidence from Microfinance. Am Sociol Rev. 82(3),542–67.

[9]. Hauret, L, Williams, DR. (2017). Cross-National Analysis of Gender Differences in Job Satisfaction. Industrial Relations: A Journal of Economy and Society, 56(2),203–35.

[10]. IBM Corp. (2020). IBM Corp.

[11]. RStudio Team . Boston: PBC; (2020). Available from: http://www.rstudio.com/

[12]. Hahm, SY, Gu, M, Sok, S. (2024). Influences of communication ability, organizational intimacy, and trust among colleagues on job satisfaction of nurses in comprehensive nursing care service units. Front Public Health.

[13]. Dindia, K, Allen, M. (1992). Sex differences in self-disclosure: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin.,112(1),106–24.

[14]. Mason, ES. (1995).Gender Differences in Job Satisfaction. The Journal of Social Psycholog,135.

Cite this article

Zhu,Y. (2024). Exploring the Gender Disparities in the Impact of Communication Skills on Job Satisfaction. Lecture Notes in Education Psychology and Public Media,54,44-49.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Education Innovation and Philosophical Inquiries

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Bylund, CL, Makoul G. (2024). Empathic communication and gender in the physician–patient encounter. Patient Education and Counseling. 8, 7–16.

[2]. Holm, A. (1999). Pedagogical methods and affect tolerance in medical students. Medical Education.,33(1),14–8.

[3]. Guadagno RE, Cialdini RB. (2002) Online persuasion: An examination of gender differences in computer-mediated interpersonal influence. Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice. Mar;6(1),38–51.

[4]. Ecke,s T, Trautner HM,(2012). editors. Developmental Social Psychology of Gender: An Integrative Framework. In: The Developmental Social Psychology of Gender [Internet]. 0 ed. Psychology Press; 17–46.

[5]. Weis,s DJ, Dawis RV, England GW. (1967) Manual for the Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire. Minnesota Studies in Vocational Rehabilitation.;22,120–120.

[6]. Muska,t B, Reitsamer, BF. (2019) Quality of work life and Generation Y: How gender and organizational type moderate job satisfaction. Personnel Review.49(1),265–83.

[7]. Eagly, AH.( 1987).Reporting sex differences. American Psychologist. Jul;42(7),756–7.

[8]. Doering L, Thébaud S. (2017).The Effects of Gendered Occupational Roles on Men’s and Women’s Workplace Authority: Evidence from Microfinance. Am Sociol Rev. 82(3),542–67.

[9]. Hauret, L, Williams, DR. (2017). Cross-National Analysis of Gender Differences in Job Satisfaction. Industrial Relations: A Journal of Economy and Society, 56(2),203–35.

[10]. IBM Corp. (2020). IBM Corp.

[11]. RStudio Team . Boston: PBC; (2020). Available from: http://www.rstudio.com/

[12]. Hahm, SY, Gu, M, Sok, S. (2024). Influences of communication ability, organizational intimacy, and trust among colleagues on job satisfaction of nurses in comprehensive nursing care service units. Front Public Health.

[13]. Dindia, K, Allen, M. (1992). Sex differences in self-disclosure: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin.,112(1),106–24.

[14]. Mason, ES. (1995).Gender Differences in Job Satisfaction. The Journal of Social Psycholog,135.