1. Introduction

Bilibili is a video sharing website from China, which was established on June 26, 2009. At first, Bilibili was a video website that allowed users to create and share ACG (animation, comics, and games) content [1]. Following over a decade of development, Bilibili has established a high-quality content ecosystem centered around its users and creators [2]. At the same time, with continuous development, the content on Bilibili is gradually covering a wide range of fields, such as anime, music, games, knowledge, vlogs, fashion, etc [3]. Among them, vlogs, games, and anime are the main content categories of Bilibili [3]. These videos are mainly Professional User Generated Videos (PUGV), which refers to videos created by users with expertise in their respective fields or those who have become familiar with a specific domain through learning and research. These video creators produce a series of relevant, carefully crafted, and edited videos within their professional or well-studied areas [4]. Such creative content gained a lot of popularity among the viewers. For example, as of June 2019, there are over 1.8 million gaming influencers on Bilibili, posting 21 million game-based videos, with 60.1 billion cumulative views [5]; Through these videos, which include game reviews and live streams, the influencers of Bilibili have changed the game industry in China [5]. Bilibili has become the largest single-player indie game content hub and one of the leading platforms for gaming videos in China [6]. In addition, Music is another popular genre on Bilibili, which gathers a large number of music creators and music lovers. Bilibili has become one of the largest original music communities in China. It is precisely because of the collision and interaction of these creators that more and more high-quality music works are created here [5].

At the beginning of 2023, it started to appear that some influencers of Bilibili announced that they would stop updating and also said that they would not upload any new content in the future. Subsequently, on March 30, “-LKs-”, an influencer of Bilibili with 3.11 million followers, released a video titled ‘An announcement of temporary stop updating’ . The following day, another famous influencer with 3.833 million followers Handsome King Wang, released a video titled ‘I’m leaving now, hope to see you again’. In this video, he announced his decision to stop updating on Bilibili. Since the beginning of 2023, many influencers of Bilibili have decided to stop updating. These influencers are from different genres, and they maintain fan bases ranging from 10,000 to over 1 million. Later, even influencers with more than 3 million followers announced that they decided to stop updating on Bilibili. On 2 April 2023, the hashtag “#Vloggers are quitting Bilibili” appeared on the Sina Weibo Hot Search List and ranked first on it, reaching 420 million views on the same day. Therefore, this phenomenon aroused the attention and lots of discussions of the public and the media.

The influencers who have announced the decision to quit Bilibili come from various genres. Additionally, each of them has different reasons for “quitting” the platform . For example, on January 12, 2023, one account of the Movie genre, Have you watched movies, who has 1.029 million followers, announced that it would stop updating because it was “unable to make ends meet financially”. From the beginning of the year to the present, some influencers have also claimed that they would “stop updating” in the Game genre, which is one of the largest content categories of Bilibili. On January 30, one influencer of the Game genre at Bilibili, Hua fh0486 Hua, also announced that he had to stop uploading due to “encountering bottlenecks and other complicated factors”. Similarly, Handsome King Wang, another well-known influencer in the Game genre, also decided to stop updating. In his video announcing this decision, he confessed the reasons for stopping updating. The main reason is that creating vidoes on Bilibili is “not profitable, even leading to losses”; and the account's operation is not sustainable given that it relied entirely on the early benefits gained from the rapid development of Bilibili. The second reason is that he was so tired of keeping updates so that he “wanted to give himself a long break.”

More and more people are starting to pay attention to this phenomenon as a growing number of influencers are announcing that they decided to stop updating. This is not only because many influencers have decided to stop updating since the beginning of the year, but also many Bilibili’s users have found that their favourite influencers have also decided to stop updating. People began to worry about the status of these influencers, and also began to feel anxious about whether the future development of Bilibili would suffer a significant impact. As a result, the phenomenon of “vloggers quitting Bilibili” started to spread and became a hot topic of conversation for China’s domestic internet. After the phenomenon aroused the attention of public opinion, many influencers of Bilibili also joined the discussion, sharing their own situations. Among them is “Zero-talent shooter”, an influencer with 472,000 followers at Bilibili. He was an athlete before, so most of his early videos released on Bilibili were mainly about basketball and other sports; at the same time, he also released some videos about his daily life. Following the large-scale concern over the “stop updating” phenomenon on Bilibili, he posted a video titled “Why I decided to stop updating? What about the future? Feelings from a heartbroken Bilibili influencer” on April 5, 2023. In this video, he gave a detailed explanation of why he stopped updating based on his personal thoughts about this phenomenon and his experience of releasing videos on Bilibili so far. In this video, firstly analyzed why there is a trend of “quitting Bilibili” among influencers; secondly, he summarized the possible impact of this phenomenon to the influencers on Bilibili. The video ends with a discussion on the current state of Bilibili and what to do next for influencers.To study and analyze the followers’ attitudes toward Bilibili influencers’ stop updating phenomenon, this research focuses on examining the users’ comments under this the video

After the release of this video, a total of 1,172 comments have been received as ofJune 18, 2023. In these comments, some users expressed regret and reluctance for his decision to stop updating, whom they had been following for a long time; at the same time, some users had a heated discussion about the reasons for the “stop updating” phenomenon mentioned in the video. For example, some reflected on the current situation of video creation of the Bilibili influencers. Besides, there were also discussions on the income earned by influencers from releasing and updating videos on Bilibili. Some comments even discussed the current operation of video platforms in China. In addition, some influencers of Bilibili also joined in the comments, explaining their own feelings and their current living conditions as content creators on Bilibili. The comments demonstrated a variety of users’ sentiments and attitudes triggered by this video about the “stop updating” phenomenon on Bilibili.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Bilibili’s unique characteristics compared with other platforms

Bilibili sets itself apart from other Chinese online video platforms with its unique characteristics. Initially envisioned as a specialized platform within the Chinese online landscape, Bilibili is a video-sharing website that centers on the production and dissemination of ACG (anime, manga, and games) content. The most important feature of Bilibili is “Danmaku”, which refers to instant comments on the screen of the video; most of them are short, concise, and often limited to one or two sentences or even one word. “Danmaku” originated from Japanese Internet culture and was first launched in 2006 by Niconico, a video website operated by a company called DWANGO [7]. Because the comments appear to fly across the screen like flying bullets, the feature is therefore called “Danmaku”, meaning ‘bullet screens’ in Japanese. In 2008, AcFun, an ACG video sharing website from China, took the lead in introducing this feature, and other streaming media platforms such as Bilibili, Douyu, and Youku have also added this feature one after another [8].

Over time, Bilibili has cultivated a robust ecosystem of top-tier content revolving around its user base and content creators. However, within a short span, state-based accounts emerged on the platform. For instance, state-affiliated accounts such as China Central Television (CCTV) established their presence on the platform [9]. Subsequently, Tencent, a major tech conglomerate in China, assumed a commanding role in the platform’s operations, resulting in Bilibili’s close integration with both state authorities and capital interests [9]. Bilibili became enmeshed with both state ideology and commercial interests, necessitating a balance between fostering positive content and attracting investments [10], [11].

Unlike YouTube’s tensions regarding user-generated versus commercially-produced content, Bilibili has refrained from integrating in-stream advertising [12]. In-stream advertising refers to ads inserted before (pre-roll), during (mid-roll), or after (post-roll) a video, each with varying durations and interactive features [13]. Nevertheless, Bilibili must navigate the interests of various stakeholders, shaping vlogging practices and production dynamics on the platform [14]. Vlogging, a video genre dedicated to presenting and sharing individuals’ daily lives, is prevalent on various social media platforms [9]. YouKu and Tudou were the main video streaming platforms in China when vlogging first gained popularity [15]. That was the time when vlogging had not yet garnered significant attention, and there were relatively few content creators operating under the “vlogs” category. Owing to competitive dynamics and collaborative endeavors among various platforms within China [16] vlogging swiftly assimilated into the socio-economic-cultural fabric of China and currently undergoes widespread adoption in the country. To realise the potential of vlogging, Bilibili committed to increasing vlog interaction and production [9], making Bilibili one of the major platforms in China for vloggers to share content and interact with the users on the platform.

2.2. An institutional perspective on Bilibili

Currently, there are numerous studies discussing the institutional perspective in platform studies, with a particular focus on the impact of digital platforms on cultural production. For example, Wang [9] noted that cultural industries are increasingly reliant on digital platforms, and the spread of these platforms is leading to a trend of “platformization”, wherein economic, governmental, and infrastructural aspects permeate the web and app ecosystems, drastically altering the way that the cultural industries operate. Additionally, Poell, Nieborg, and Duffy [17] suggested an institutional standpoint to analyse the impact of platforms on cultural production through factors such as market dynamics, infrastructure, and governance. According to this viewpoint, platforms are seen as consisting of three key elements: (1) “multisided markets”, which promote business dealings between content/service producers and end consumers [17]; (2) “platform infrastructure”, such as networks and databases, that furnishes cultural producers with the means to generate, disseminate, market, and gain revenue from content [17]; (3) “platform governance”, which affects more general laws governing public areas by influencing how material is created, shared, promoted, and monetized online [17].

Furthermore, Wang [9] also analysed how user-generated content (UGC) platforms employ a strategy of commissioning creators, treating them more like labor under contractual arrangements rather than establishing genuine partnerships. These platforms, such as Bilibili, encourage cultural production by offering financial incentives to creators, but concurrently exploit them as a source of labor to generate profits for the platform. Moreover, once the platform attains its content and creator objectives, it begins selecting partners by imposing implicit increases in monetization requirements. To explain this strategy, Wang [9] analyzed the tiered revenue-sharing rules implemented by the YouTube Partner Programme (YPP), which has transformed the content creation landscape by providing higher visibility and revenues for content that is more suitable for advertising. Confronted with a vast array of video content, YouTube shifts its focus from content creators to content “monetizers” in order to maximize its own profits [18]. Viewing creators primarily as monetizers rather than content creators reduces their autonomy and could jeopardize the sustainability of their income, relegating them to subordinate roles on the platform [19].

At the same time, among the numerous digital platforms accessible today, Bilibili is exerting an impact on the economic worth of content creators. According to Wang [9], these digital platforms employ a range of methods to entice producers and play a crucial role in the realm of content generation. The degree to which producers are visible determines their economic worth, regardless of the particular commission agreements or graded income schemes in place. This visibility encompasses how cultural content is ranked, ordered, and discovered on platforms, which are influenced by the curation strategies employed by the platform [17]. These approaches encompass both editorial curation and algorithmic curation, ingrained in the established norms and values of the platform [20]. Moreover, according to Craig et al. [16], pillarization is taking place on social media platforms. The term “pillarization” initially denoted the societal division into “pillars” representing networks of organizations linked to religious and ideological subcultures [21]. Therefore, Craig et al. [16], p.86 point out that platforms can be perceived as segmented, influenced by factors such as “geography, class, and personal hobbies or affinities”. This segmentation is exemplified by platforms like Douyin and Kuaishou in China, which target specific user demographics [16].

2.3. Bilibili’s business model: relationships among the platform, vloggers, and advertisers

China’s online video platforms are currently expanding quickly and playing a significant role in the online commerce. Profitability must be taken into consideration if an online video platform hopes to grow steadily over time and establish a presence in the extremely competitive market. Many of these studies concentrate on the vloggers and Bilibili’s business model. For example, advertising is one of the most important forms of commercial profitability, and the development and operation of Bilibili are inseparable from advertising. Bilibili’s advertisements are also diverse and unique. Liu and Sun [22] found that Bilibili abandons and substitutes for traditional advertisement dissemination methods. Bilibili sets advertisements at the bottom of each video; users can click on the advertisements to get more detailed information [22]. Additionally, advertising campaigns on Bilibili come in a variety of forms [22]. Sometimes the ads are designed to appear on the video’s bullet screen. Such ads are usually designed as cartoon patterns and are large in size, mostly occupying nearly a quarter of the screen area. There are also hidden ads that pop up at the click of a button [22].

At the same time, Liu [23] pointed out that while the current market landscape has been dominated by Youku, iQIYI, and Tencent, other video platforms are still maintaining a good momentum of development [23]. Take Bilibili as an example, the study explored its monetization strategies, analysed the difficulties it faces in the process of development, and put forward corresponding development recommendations [23]. The study also points out that Bilibili’s current business model relies on four main ways: game agency, live streaming and value-added services, advertising partnerships, and e-commerce [23]. However, Bilibili’s current business model is still simple and faces difficulties such as copyright crisis and competition from other platforms [23], [24]. Additionally, the inadequate content regulation mechanism poses challenges for Bilibili [24]. Moreover, an examination of Bilibili’s financial statements spanning from 2017 to 2020 revealed an irrational asset structure that is not conducive to the platform’s long-term and sustainable growth [24]. This structural issue has resulted in a consistent increase in net losses for the platform [24]. To compound these challenges, Lu and Wu (2021) noted that Bilibili also grapples with difficulties in achieving profitability through advertising and contends with the competitive pressures posed by other video-sharing websites.

Nevertheless inserting advertisements to videos can be an effective way to promote the advertised products or brands and gain profits for the platform. Such advertisements usually require direct collaboration between advertisers and vloggers in a sponsored video, where vloggers ill intentionally expose a specific brand or a product to impress the viewers. This advertising strategy has become the mainstream of product advertising and marketing on Bilibili [11].

The impact of such sponsored content on consumers and user behaviour has also been extensively explored in the existing literature. Cai’s [25] study examines the current development of the advertising model utilized by Bilibili’s vloggers. It analyzes issues such as the prevalence of advertisements or sponsorships embedded within the vloggers' videos [25]. Given that a considerable proportion of Bilibili’s vloggers lack expertise in advertising, they often struggle to effectively promote the product in a manner that maximizes benefits both for the advertisers and themselves. Consequently, this results in content that lacks a sufficient degree of professionalism and may, in some cases, even be misleading [25].

After synthesizing the literature on Bilibili’s development, the institutional perspectives of Bilibili, and how Bilibili and its influencers monetize, this study hereby raises the following research question:

Research Question: What are users’ responses to Bilibili vlogger’s “stop updating” announcement?

3. Method

To address the research question, this study integrates literature on institutional perspective, platform economy, and sponsorship disclosure. It employs a text analysis approach on user comments to uncover Bilibili users’ responses to Bilibili vloggers’ “stop updating” announcement. In communication and media studies, textual analysis includes a range of research techniques, including discourse analysis, narrative analysis, content analysis, and critical discourse analysis [26]. According to McKee [27], the specific textual analysis used in this research is a methodology to “understanding how members of various cultures and subcultures perceive themselves and how they integrate into the world they live in” [27]. As per McKee’s [27] assertion, textual analysis allows scholars to decipher various texts such as movies, TV shows, periodicals, ads, clothes, graffiti, etc., with the aim of comprehending how individuals in distinct cultures and unique eras comprehend their surroundings [27]. Therefore, textual analysis is appropriate in this study to investigate user narratives through comment analysis, with the goal of comprehending how users react to the announcements made by Bilibili vloggers to “stop updating”.

3.1. Sampling

The sample for this research was collected from the comment section of a video uploaded by a Bilibili vlogger, “Zero-talent shooter”, a former athlete and Tencent programmer. The types of videos posted by this vlogger primarily cover sports, knowledge, and daily life. As of the writing of this article in 2023, “Zero-talent shooter” has amassed over 490,000 followers on Bilibili, and the total views for the 74 videos posted by this vlogger have reached an impressive 61.776 million.

The primary criteria for selecting this vlogger were his successful presence on the platform and the level of public engagement in the comments section. The video chosen for this study is titled “Why decided to stop updating? What about the future? Feelings from a heartbroken Bilibili influencer”. The monologue within the video is narrated by “Zero-talent shooter” in Chinese. These comments were transferred to a spreadsheet for the purpose of analysis.

As indicated by the video title, the video aims to explore the phenomenon of Bilibili vloggers announcing “stop updating”. In the video, the content creator, “Zero-talent shooter”, discusses the reasons behind the occurrence of the “stop updating” phenomenon, its impact on different stakeholders, and suggests strategies for Bilibili to address this issue.

Firstly, “Zero-talent shooter” attributes the “stop updating” phenomenon to Bilibili’s characteristics such as “persistently avoiding overlay ads”, coupled with the weak monetization capabilities of vloggers on the platform and the imbalance in income provided by advertisers. These factors contribute to the emergence of the “stop updating” phenomenon. Secondly, in the narrative of the video, the vlogger points out that vloggers who are already signed with the platform and possess strong “commercialization capabilities” are less affected by the “stop updating” phenomenon. Their video content is closely aligned with products, providing them with resilience in the face of this trend. On the contrary, vloggers without platform contracts face the greatest impact, as their monetization capabilities on Bilibili are not guaranteed, forcing them to choose between “money” and “popularity”, irrespective of their commercialization capabilities. Additionally, in the concluding remarks of the video, “Zero-talent shooter” discusses what Bilibili can do in response to the “stop updating” phenomenon. He suggests that Bilibili could introduce overlay ads as a monetization strategy similar to YouTube. Furthermore, “Zero-talent shooter” advocates for a reevaluation of Bilibili’s brand positioning. He emphasizes the increasing significance of vertical and short-form videos on Bilibili, citing a 400% year-on-year growth in daily views for vertical videos and a fivefold increase in interaction rates for vertical video ads compared to horizontal ones. However, “Zero-talent shooter” acknowledges that the challenges faced by Bilibili, including the “stop updating” phenomenon, are not issues that can be easily resolved with “one or two adjustments”. Simultaneously, “Zero-talent shooter” advises fellow vloggers to adapt to the current “rules of the game” and strive to avoid being sidelined.

The video vlogger “Zero-talent shooter” encourages his followers to share this video and actively engage in discussions and exchange of ideas in the comments section. As of the data collection in July 2023, since its release in April 2023, the video has accumulated over 420,000 views and 1,176 comments.

3.2. Analysis

The textual analysis involves 1,176 comments. The researcher gathered all comments from the video for scrutiny, as these comments offer substantial data for comprehending user reactions to the “stop updating” announcement by Bilibili vloggers. All comments were amassed in August 2023 and cataloged in a Google spreadsheet for subsequent analysis.

For data analysis, this research used the constant comparative approach, which is a two-step procedure [28]. First, during the initial phase of coding, all comments were input into a designated column within the spreadsheet; subsequently, an additional column was established to document the thematic elements and concise codes that arose during the examination of the comments. Following this, the researcher meticulously recorded the verbatim of every comment and systematically engaged in a comparative analysis line by line. Throughout this process, the study’s comparing procedure was made easier using Google Sheets’ sorting functionality. Following the review of every comment and the identification of overarching themes, codes like “Ecosystem”, “overlay ads”, and “Bilibili’s business model” emerged in the corpus.

In the second coding phase, the researcher systematically documented the themes identified in the initial round and organized them into more abstract conceptual categories [28]. This two-step process included revisiting annotations in the spreadsheet, reorganizing materials and associated codes, and conducting further literature review on internet video platform business models. The objective was to delve deeper into emerging themes and enhance their precision through additional inductive processes. During this phase, the researcher gradually clarified the essence represented by newly identified themes, transitioning into the stage of narrative writing and data analysis.

4. Findings and Discussion (Maybe use “Results” instead)

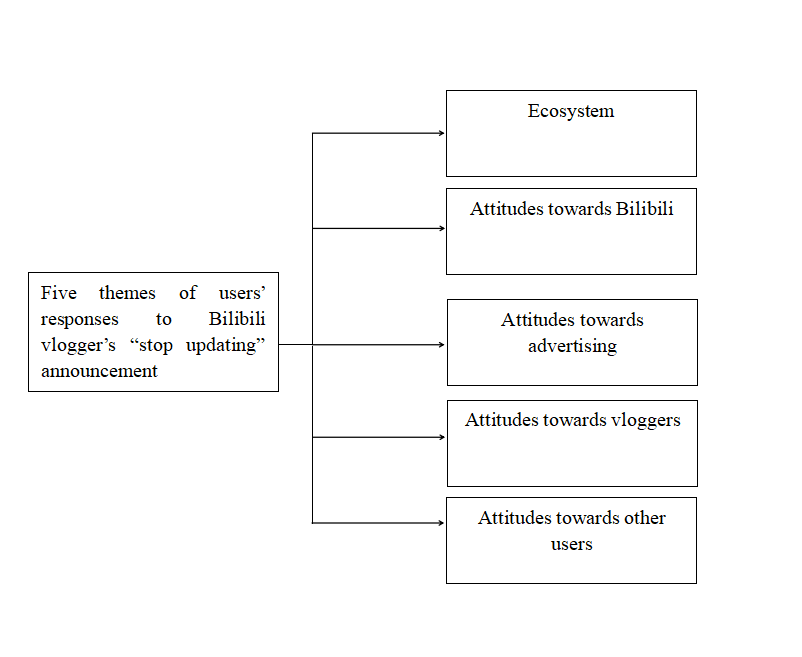

The findings of the data analysis reveal how Bilibili users respond to the announcement made by the Bilibili vloggers who decided to “stop updating” on Bilibili. This section explores how these users reacted to such announcements and categorises the comments posted under the video into five distinct themes: attitudes towards the ecosystem, attitudes towards Bilibili, attitudes towards advertising, attitudes towards vloggers, and attitudes towards other users.

Figure 1: A typology of Bilibili users’ response to Bilibili vlogger’s “stop updating” announcement.

4.1. Attitudes towards the Ecosystem

In the comments below this video, a notable surge of reactions and responses from Bilibili users has emerged in response to the “stop updating” phenomenon among Bilibili vloggers. Within these comments, several users have initiated comparisons between Bilibili and alternative platforms, trying to make sense of the reason behind such a phenomenon from the perspective of Bilibili’s ecosystem. For instance, one user articulated the following perspective:

“Douyin has done an excellent job with commercialization. Its marketplace is right there at the top-level entrance, and talents from various fields may potentially receive commercial opportunities in the future.”

Furthermore, other users have introduced comparisons with platforms such as “Douyin” and “Kuaishou” into their commentary. These users have embarked on assessments that juxtapose Bilibili with these alternative video-sharing platforms. Within these comments, expressions of admiration and recognition have surfaced, particularly concerning the “commercialization” or “monetization capabilities” of platforms like “Douyin” and “Kuaishou”. Certain users have even underscored the notion that Bilibili finds itself at a pivotal juncture, necessitating decisions between “transition” and “endurance”. Nevertheless, there are also expressions of the belief that, when juxtaposed with other platforms, Bilibili is “filled with good content” and remains “quite important”. In these comments, Bilibili users engage in comparative evaluations involving Bilibili and other platforms, with a primary focus on “Douyin” and “Kuaishou”. These comparative assessments span various facets, including the platforms’ monetization capabilities, thereby underscoring Bilibili’s position in relation to other platforms. Collectively, these comments serve as an indicator of Bilibili users’ responses to the announcement by Bilibili’s vloggers regarding their decision to “stop updating”.

Moreover, a segment of users has delved into an examination of video formats, specifically vertical and short-form videos, on Bilibili. For instance:

“I’ve mentioned countless times that horizontal and vertical formats should be separated. Audiences are fundamentally two different groups of people. Sometimes, creators like me with lower-quality content get heavily promoted on vertical formats, making it to the popular homepage on the PC version. Then, I have to face endless insults from viewers in horizontal formats. I don't want to occupy the recommendation slots of high-quality content creators. Just let me stay in the vertical format videos category. If users come across it and want to watch, they can. If they don’t, they can swipe away. Keep it separate from horizontal content. High-quality, long-form horizontal format videos should still be featured on the Bilibili homepage as per users’ traditional habits. It’s straightforward; just add two sections at the bottom of the interface, one for horizontal and one for short videos, and keep them separate.”

The introduction of Bilibili’s vertical video format has triggered a discernible response among users. Users expressing sentiments of this nature have brought to the fore the dichotomy between two distinct video formats: horizontal and vertical. According to these users, the “horizontal” format should be designated for long-form videos, while the “vertical” format should be reserved for short-form videos. Furthermore, these individuals advocate for a clear differentiation between horizontal and vertical formats, asserting that videos intended for horizontal viewing should be seamlessly adapted to the vertical format. Nevertheless, some users have voiced their resistance to this transition, as evidenced by comments such as “reluctant to view vertical video” and advocating for “the discontinuation of the vertical video format”. In summary, the comments made by these users manifest a comparative analysis between Bilibili’s video format and the prevailing vertical and short-form videos within the ecosystem. These users firmly believe that the disparity in video formats between horizontal and vertical orientations holds substantial sway in the contemporary landscape.

The comments also feature expressions from certain users highlighting concerns about economic decline within the ecosystem. An illustrative comment reads as follows:

“After watching the video, I once again felt the powerlessness of an individual in the face of the ecosystem.”

In a similar vein, users have articulated sentiments around the notion of “economic decline” within the ecosystem, attributing it to a “diminished capacity for consumption”. This has engendered a sense of “weakness” among users—including content creators—within the ecosystem. Such comments collectively convey that users' responses to Bilibili vloggers’ announcement to “stop updating” have been notably centered on the economic challenges confronting the ecosystem, resulting in a palpable feeling of “weakness” among users.

4.2. Attitudes towards Bilibili

The second perspective of the results of the analysis reveals users’ attitudes towards Bilibili. Some of the users discussed Bilibili’s business model in their comments, and the content directly refers to its monetization strategies and the sustainability of its business operation. Furthermore, some users embarked on a comparative analysis of Bilibili’s past and present states, observing that the platform has undergone notable transformations from its earlier iterations. A few illustrative examples are outlined below:

“Not having overlay ads was a public promise by Bilibili.”

A significant portion of users raised the issue of Bilibili’s initial “promise” of an ad-free experience, underscoring that this absence of advertisements was originally a defining “feature” setting it apart from other video platforms. However, this initial “promise” has now posed challenges in terms of monetizing Bilibili, rendering it “increasingly difficult” to achieve profitability. Consequently, these users contend that Bilibili’s decision to “introduce advertisements” is preferable to the potential demise of the platform. Moreover, some users argue that the inclusion of advertisements by Bilibili amounts to a “compromise of integrity” and tarnishes the platform’s ambiance. As such, this cohort of users perceives the abandonment of the initial “promise” in favor of pursuing “profit” as a “deleterious course of action”. It is evident that users have expressed their nuanced stance on Bilibili’s existing business model and discussed whether or not to change the “promise” of no ads.

“Bilibili is no longer what it used to be”

Furthermore, apart from the discourse surrounding Bilibili’s business model, several comments have explicitly alluded to a perceived transformation within Bilibili. For instance, one user wrote: “Bilibili is no longer the Bilibili of a few years ago”; while others expressed sentiments such as, “I yearn for the Bilibili of the pre-2018 era”. In a similar vein, certain users added to this narrative by suggesting that Bilibili’s vloggers will inevitably opt to “stop updating” at some point. These comments collectively convey the prevailing user sentiment that Bilibili is no longer what it used to be.

4.3. Attitudes towards advertising

The third perspective is Bilibili users’ attitudes towards advertising. After analysing the comments, this study found that Bilibili users’ attitudes towards advertising were expressed on multiple levels, and their focus was not only placed on different forms of advertising but also on the discussion of vloggers’ monetization.

“The (sponsored) video feels really bad, similar to making a plate of dumplings just for the sake of using this particular vinegar.”

In these comments, a significant portion of users believe that much of today’s sponsored video is “designed for this ad”. As mentioned in the comment, a user considers advertisements as “a bottle of vinegar” and videos as “a plate of dumplings”. Comments like this express that a video created solely for the sake of advertisements is akin to preparing “a plate of dumplings” just for “a bottle of vinegar”. This analogy underscores the notion that content is being created primarily as a complement to the advertisement, similar to preparing a meal specifically to pair with a condiment. Some even think that “advertisements should be separated from content”. These comments indicate an attitude towards native ads in videos, which they believe should not detract from the video and thus the “feel” of the video.

“The advertisements on YouTube are really well-made.”

Simultaneously, a subset of users articulated their perspectives on overlay ads. Predominantly, these users conveyed their willingness to accept overlay ads on YouTube. Many users acknowledged the quality of certain overlay ads on YouTube, deeming them as “truly effective”. A few users went further, suggesting that Bilibili could potentially “draw inspiration” from the overlay ads featured on YouTube. These comments collectively signify users’ openness and acceptance of overlay ads similar to those encountered on YouTube when it comes to Bilibili.

Furthermore, certain users expressed their viewpoints through comments such as, “The problem is the poor consumption; merchants prefer advertisements that directly stimulate consumption, reduce and modify cognitive processes, and enhance brand-building advertisements.” This perspective suggests that the efficacy of advertisements should prioritize a more “direct” approach aimed at “boosting consumption”, emphasizing the current advocacy for ads that are good for conversion. However, contrasting sentiments were also articulated, as seen in the comment: “Does the addition of overlay ads mean there are no embedded ads within the video?” This comment reflects a skeptical stance toward advertisements, positing that even with the addition of overlay ads, video content may still contain embedded advertisements.

“Pinduoduo has supported many content creators.”

In addition to attitudes towards various advertising formats, users have also expressed their opinions on vloggers’ monetization. For instance, certain comments have highlighted that Bilibili vloggers currently rely on sponsorships from live betting platforms or promote products through links to Pinduoduo, a prominent Chinese e-commerce platform known for its strong reputation [29]. However, in recent years, problems such as fake products and low product quality have affected this platform [29]. Although these sponsorships from Pinduoduo and live betting platforms may not enjoy wide recognition among users, many believe that they still provide substantial support to numerous Bilibili vloggers. Some users contend that investment-focused or instructional vloggers on Bilibili are “financially well-off”. Conversely, there are comments suggesting that Bilibili’s “knowledge genre” vloggers face “challenges” and “struggles” in sustaining their content creation endeavors. Consequently, this study elucidates users’ attitudes toward vloggers’ monetization, encompassing their perspectives on the existing monetization approaches of vloggers as well as their attitudes regarding the monetization strategies of various vloggers from different genres on Bilibili.

4.4. Attitudes towards vloggers

The fourth perspective of this study is Bilibili users’ attitude towards vloggers. The analyses revealed that some users expressed their own thoughts on Bilibili’s vloggers’ “stop updating”. They also pointed to the reason why vloggers announced to “stop updating”. The comments are summarised below:

“There are too many vloggers on the platform.”

Comments resembling such attitude have surfaced with a notable frequency during the analysis process. These comments predominantly convey the notion that the proliferation of vloggers on Bilibili has reached a juncture where it has outpaced the corresponding growth of the user base, despite the increasing number of vloggers and the content they generate. Consequently, this phenomenon has emerged as a pivotal “factor” motivating vloggers to announce their decision to “stop updating”. Moreover, certain users contend that the influx of vloggers aspiring to attain “full-time” or “professional” status, primarily driven by financial incentives, has also contributed to vloggers declaring their intention to “stop updating”. In some instances, users even postulate that had vloggers approached video creation purely as a “passion” or “hobby”, the current state of affairs on Bilibili might have taken a different trajectory. Hence, the analysis elucidates that a segment of users attributes the proliferation of vloggers on Bilibili, which has fostered intensified competition among them, as a key catalyst prompting some vloggers to decide to “stop updating”.

“Bilibili using the ‘stop updating’ trend as a setup for embedding future ads.”

Simultaneously, certain users have offered “speculations” in their comments, suggesting that Bilibili may strategically utilize the recent announcements made by selected vloggers declaring their intention to “stop updating” as a means to pave the path for subsequent “ad placements” or “embedded advertisements”. These comments shed light on the conjecture held by some users that the vloggers’ decisions to “stop updating” might potentially serve as a mere publicity stunt. While a handful of users acknowledge that this line of thinking may tread into the realm of conspiracy theory, they nevertheless convey the belief that Bilibili could exploit this opportunity to generate buzz and seamlessly integrate advertisements into the platform.

“It’s time to let them step down and bring in a new batch of talent.”

Moreover, a segment of Bilibili users has articulated the perspective that at present, “in every industry, there are individuals unable to sustain their endeavors”, and some users contend that these vloggers opting to “stop updating” should “clear the path for emerging talent”. As a result, certain users explicitly assert in their comments such as “every industry adheres to the principles of natural selection”. These comments offer insight into how these users interpret the vloggers’ decisions to “stop updating” as a manifestation of “survival of the fittest”.

4.5. Attitudes towards other users

The final perspective revealed from the data analysis is Bilibili users’ attitudes towards other users. These users focused on other Bilibili users in their comments and attributed the reason for the “stop updating” phenomenon to other users.

“Characteristics of Bilibili users: Low income and picky.”

Within these comments, a considerable portion of users have expressed the sentiment that some of the current Bilibili users are acting “strangely”. Furthermore, these comments suggest that these users are “poor” and even “critical”, “imposing various expectations” on Bilibili’s vloggers, which in turn have had a “negative impact” on the vloggers. It is evident from these comments that this subset of users is directing their dissatisfaction towards other Bilibili users and “mocking” them within their comments. Consequently, this reflects their reaction to the vloggers’ announcements of “stop updating”, which is rooted in the behavior of other Bilibili users.

“It’s quite strange that some users have high demands but don’t let vloggers make money.”

Additionally, some users believed that other Bilibili users have “high expectations” while also discouraging vloggers from accepting advertisements or sponsorships to generate income. Users who make these comments express their confusion regarding this phenomenon. They view the actions of some Bilibili users as “double standard” regarding the dilemma between vloggers’ monetization and content quality.

“Let vloggers make a profit by overlay ads, all for high-quality content.”

In addition to the comments mentioned earlier, there is another subset of users expressing distinct viewpoints in their remarks. Within this category of comments, these users emphasize that vloggers can consistently produce “high-quality content” when they can “generate income”. Consequently, they propose that vloggers can monetize their content through methods such as “incorporating advertisements”, which would, in turn, facilitate the creation of “premium content”. As such, these users’ comments convey an attitude that encourages fellow users to support and pay for premium content in response to the vloggers’ announcements of “stop updating” on Bilibili.

In conclusion, the above sections have illustrated the research findings through examples and explanations. They have explored the responses of Bilibili users to the announcements made by Bilibili’s vloggers regarding their “stop updating” and how these users have reacted to these announcements from five perspectives: attitudes towards the ecosystem, attitudes towards Bilibili, attitudes towards advertising, attitudes towards vloggers, and attitudes towards other users (Table 1).

Table 1: Categories of Bilibili users’ reactions toward Bilibili vlogger’s “stop updating” announcement.

Themes | Codes | Representative Comments |

Ecosystem | Comparison with other platforms (YouTube, Tiktok, etc) | You make short videos, so why wouldn't I go to more mature platforms like Douyin or Kuaishou? |

A Douyin influencer with over two million followers, and there are several comments below, with tens of thousands of likes, and even the comments on the comments have reached over ten thousand, I'm amazed. | ||

Douyin has done an excellent job with commercialization. Its marketplace is right there at the top-level entrance, and talents from various fields may potentially receive commercial opportunities in the future | ||

Comparison with other video formats (verticle), short-form video | I just want to say, no vertical format videos. I haven't downloaded apps like Kuaishou or Douyin for so many years just because I don't want to watch vertical format videos. | |

The problem with Bilibili is that when I'm watching a long video, there's a vertical format video recommendation in the middle. I click on it and watch it, but when I scroll down, the next video is in 20-minute horizontal format. I can tolerate the combination of horizontal and vertical in horizontal format videos, but if you're going to do it, just keep all the horizontal format videos out of the vertical format video section. | ||

I’ve mentioned countless times that horizontal and vertical formats should be separated. Audiences are fundamentally two different groups of people. Sometimes, creators like me with lower-quality content get heavily promoted on vertical formats, making it to the popular homepage on the PC version. Then, I have to face endless insults from viewers in horizontal formats. I don't want to occupy the recommendation slots of high-quality content creators. Just let me stay in the vertical format videos category. If users come across it and want to watch, they can. If they don’t, they can swipe away. Keep it separate from horizontal content. High-quality, long-form horizontal format videos should still be featured on Bilibili homepage as per users’ traditional habits. It’s straightforward; just add two sections at the bottom of the interface, one for horizontal and one for short videos, and keep them separate. | ||

Economic decline | After watching the video, I once again felt a sense of powerlessness as an individual in the ecosystem. | |

It feels like viewers have been getting free content for too long because of insufficient purchasing power. | ||

Attitudes toward Bilibili | Bilibili’s Business model, Monetization strategies, sustainability | When I first joined Bilibili, I actually had a question ❓ Why didn't they have ads at the beginning? And there are so many excellent long videos to watch, and you don't need any VIP. Can they make money like this? I've been enjoying this almost for free for several years. It seems like I have to go with the flow a bit more. |

Thinking about it, if Bilibili starts inserting ads into videos in the future, it will still disrupt the atmosphere. Some videos really let me enjoy the atmosphere. But having inserted ads is better than not having Bilibili at all. | ||

Bilibili not having overlay ads is not just a feature; most of the old users know that the absence of overlay ads is a public commitment made by Bilibili. If they add overlay ads, perhaps it can save the platform in the short term, but it completely abandons integrity. I won’t go into what will happen if integrity is lost. In my opinion, this place was originally where people made videos out of interest. If you feel like you’re not making money and want to stop updating, then just stop. Your starting point is already different from the earliest batch of people who started making videos here. There’s no need to make it difficult for yourself. The ads that the vloggers accept are their own problem, and I support that without opposition. Whether it's about benefits or risks, it's all up to the creators to bear. It doesn't have much to do with the website. Back when ads were prevalent, Bilibili started with the slogan of being ad-free, and they built it up step by step. Abandoning the voice they’ve been shouting for over a decade because of profits would be a destructive change. Even if they were to change, it wouldn’t be now. It needs to be done gradually, with testing and predictions. Suddenly making such a change might keep it alive for a few more years, but it's a short-sighted move. | ||

Bilibili is no longer what it used to be | When all websites started adding overlay ads, only Bilibili refused to do so. That’s what made Bilibili, Bilibili at the time. Now, whether they add them or not doesn’t really matter because today’s Bilibili is no longer what it used to be。 | |

I miss Bilibili from before 2018, but now, for various reasons, we can't go back. Alas. | ||

Attitudes toward advertising | Attitudes toward Native advertising | I totally agree. The kind of video where it feels like they made a plate of dumplings just for the sake of using that bottle of vinegar really isn't enjoyable. It's better to keep advertisements separate from the content and be more straightforward. |

Overlay ads don’t affect the content of the work. Currently, not having overlay ads means the entire program's content is designed around the advertisement. | ||

Attitudes toward overlay ads (including pre-roll ads, mid-roll ads, and banners). | I personally think the YouTube overlay ad format is okay and acceptable, especially since you can skip them. Of course, this is just my personal opinion.[doge] | |

I have to say, even though you can skip YouTube's overlay ads in five seconds, I often end up watching them till the end because some of them are really well-made. | ||

Learning from YouTube’s 5-second ads at the beginning that can be skipped. | ||

Advocacy for ads that are good for conversion | I see the problem is the lack of consumer spending. Businesses prefer advertisements that directly stimulate consumption, reduce or change awareness, and strengthen brand-building ads. | |

Skeptical attitudes towards advertising | Does adding overlay ads mean there won’t be any embedded ads within the video itself? | |

Attitude towards vloggers’ monetization (sponsorship from PDD, gambling) | Pinduoduo has supported many content creators. | |

I really envy you! You have so many likes. But being a ‘Knowledge genre’ vlogger is so tough! I'm finding it hard to keep going. It's really challenging. | ||

Attitudes towards vloggers | competition among influencers | There are many reasons, but one unavoidable factor is that there are too many content creators. It’s been statistically proven that the number of content creators has increased tenfold over the past decade, and everyone wants to earn money through video streaming. But where are the viewers supposed to come from to support this growth? As the industry becomes more competitive and saturated, it naturally leads to price reductions and reduced efficiency, among other challenges. This phenomenon can be seen in various industries, such as the current situation in e-commerce platforms like Taobao, the new energy vehicle industry, and many others. During the Red Ocean phase of an industry’s development, attrition and consolidation are inevitable, and it's not just a single reason but a combination of factors. |

Because there are too many people, and everyone wants to do it full-time. If they only treated videos as a hobby, Bilibili wouldn’t be like this. | ||

Publicity stunt | Perhaps it’s just my conspiracy theory, but Bilibili might be using this trend of content creators pausing updates to lay the groundwork for future ad placements on the platform. | |

Here’s a prediction: Bilibili is about to start accepting advertisements. | ||

Survival of the fittest | To be frank, no matter how you put it, it all boils down to interests. I’ve noticed that most of the vloggers who’ve stopped updating have over a million followers, and some vloggers who have a smaller number of followers aren't earning as much, but they haven’t made a fuss about stopping. I believe this recent wave of creators deciding to stop updating is also Bilibili’s deliberate move. Many top vloggers have dominated the platform for a long time, and it's about time for them to step aside and make way for a new generation of vloggers. | |

In any industry, the law of the jungle prevails, but when inferior quality surpasses superior quality, it’s an utter disaster. The first priority should be to ensure that the top-tier vloggers can generate income, and it’s entirely normal for a portion of the mid-level vloggers to face challenges. The audience also needs to play a role in filtering and eliminating. We shouldn’t constantly dwell on the past or hesitate about changes. Even the management needs to undergo reform; the days of exclusively following users’ demands in the smartphone industry have long ended. | ||

Attitude towards other users | Mocking users for being poor and picking | Characteristics of Bilibili users: Low Income and Picky. |

In plain terms, it’s just that the user demographics are different. Some people think of themselves as high and mighty, making all sorts of demands. | ||

They believe other users have “double standards”. | Honestly, even though some viewers are habitually resistant to in-video ads and are starting to wonder about the YouTube model, Bilibili’s user experience is still superior. The main ones affected by Bilibili’s current model are those content creators who can’t secure business deals or high-paying sponsorships. Viewers shouldn’t clamor for changes. The day they actually change is the day you might consider leaving the platform for good. | |

It’s quite curious how some users have high demands but don’t want content creators to monetize. Besides, advertisements can be skipped, so frequent monetization attempts can understandably be off-putting. | ||

Encourage other users to pay for good content | Actually, for me right now, “getting a premium membership is my way of showing that I’m willing to pay... I'm willing to pay for quality content, but I don’t want to watch ads”. The pricing leverage hasn’t been worked out yet, and honestly, the consumption mindset in China needs to change a bit. Even if something is as cheap as a “MIXUE Ice Cream & Tea” (a bubble tea brand), it’s not free; you have to pay for it, it’s not handed out for free. | |

I think allowing content creators to choose overlay ads is actually a good idea. If it helps content creators earn a profit, I’m willing to accept it in order to support high-quality content. |

5. Discussion

Collectively, the findings of this study resonate with the literature from three main aspects: (1) an institutional perspective existing on Bilibili; (2) how Bilibili utilises vloggers as “labour” to create economic value; and (3) the limitations present in the business models of both Bilibili and vloggers.

Firstly, in line with the literature, the findings can be interpreted from an institutional perspective on Bilibili. The institutional perspective, as proposed by Poell, Nieborg, and Duffy, involves studying the impact of platforms on cultural production through factors such as market dynamics, infrastructure, and governance [17]. From this standpoint, platforms consist of three key elements: (1) “multilateral markets”, which encourage economic exchanges between content or service suppliers and end consumers [30]; (2) “platform infrastructure”, such as networks and databases, which provide cultural producers with the means to generate, disseminate, market, and profit from content [30]; (3) “platform governance”, which controls the creation, distribution, marketing, and monetization of material online, and has an impact on more general laws governing public areas [30]. Under this perspective, Bilibili users exhibit a willingness to pay for high-quality content from vloggers when vloggers announce “stop updating”. Bilibili, as a platform influenced by these expectations, encourages vloggers to provide more content to satisfy the demands of such users. This fosters a “multisided market” dynamic, promoting economic interactions between users and content creators [17]. Additionally, this perspective also applies to the relationship between Bilibili and vloggers. Within this context, Bilibili’s institutional framework incentivizes vloggers to accept various forms of advertising and earn income through advertisements. This allows the platform to serve as a tool for these content creators to create, distribute, promote, and profit from their content [30]. Furthermore, Bilibili’s platform governance plays a role in this perspective. Under the governance of Bilibili, it determines how vloggers’ content is disseminated, promoted, and monetized on the platform. In conclusion, the “stop updating” phenomenon on Bilibili can be understood through an institutional perspective.

Moreover, the findings of this study further illustrate that Bilibili employs vloggers as a form of labor to generate economic value. In essence, Bilibili motivates these content creators to produce content by offering mechanisms that stimulate their creativity. However, concurrently, it also harnesses their efforts as a source of labor to generate profits for the platform. This observation aligns with prior research perspectives, which have indicated that UGC platforms often steer content creators towards assuming the role of monetizers through contractual arrangements resembling labor contracts [9].

Thirdly, this study’s findings concur with the preceding research, illuminating constraints within the profit models of both Bilibili and its vloggers. Bilibili, which originally emerged as a subcultural community, once made an explicit commitment to abstain from incorporating preroll advertisements in its video content [9]. Despite Bilibili permitting vloggers to generate income through the creation of videos and the endorsement of products via brand advertising [24], challenges arise when products endorsed by vloggers confront issues related to quality or lack of professional validation. These circumstances can besmirch the reputation of vloggers, resulting in a dwindling follower base and potentially impacting the overall reputation of Bilibili [25]. Additionally, the revenue generated from such forms of advertising or sponsorship remains limited in comparison to preroll advertisements [24]. Therefore, as the research results demonstrate, the profit models within the Bilibili platform’s commercial framework are not significantly effective for its vloggers.

From the Bilibili users’ expressions and responses to vloggers announcing “stop updating”, it can be observed that Bilibili, as a digital platform, provides a space to sustain and diversify vloggers, significantly influencing their production, planning, and monetization on the platform [3]. In essence, Bilibili can be comprehended through an institutional perspective as a “multisided market” facilitating economic interactions between users and content creators [30]. Additionally, Bilibili’s platform embodies what can be termed as “platform infrastructure”, functioning as a tool for vloggers to create, disseminate, promote, and derive income from their content [30]. Additionally, Bilibili possesses elements of platform governance, deciding how content is generated, disseminated, promoted, and monetized on its platform, thereby impacting broader regulations governing public spaces [30].

In summary, the “stop updating” phenomenon on Bilibili carries multifaceted implications. Firstly, it has the potential to harm Bilibili’s reputation and affect its overall appeal. Concurrently, it poses challenges to Bilibili’s existing business model, as reduced video uploads may lead to decreased user engagement and advertising revenue, consequently affecting the platform's income. Secondly, content creators on Bilibili may experience a loss of their audience due to the “stop updating” trend, resulting in reduced income. Furthermore, this phenomenon opens up opportunities for other content creators to compete for attention and a larger market share, intensifying the competition among content creators on the platform. Thirdly, Bilibili users may express disappointment due to the “stop updating” phenomenon, as it restricts their access to preferred content. This may prompt some users to contemplate migrating to other platforms with more active content creators. Additionally, this phenomenon reverberates in society. For instance, it becomes a focal point of discussion on social media, highlighting the challenges that platforms and content creators face in today’s digital landscape. This discourse often extends to topics concerning platform business models, monetization strategies, and the evolving role of content creators as a new type of labor force. In conclusion, the repercussions of Bilibili’s “stop updating” phenomenon are diverse, impacting not only Bilibili, content creators, and users but also society at large.

6. Conclusion

After reviewing the research background and relevant areas, this studyfocused on a video related to the “stop updating” phenomenon on Bilibili, which was posted by one of the vloggers involved. The research specifically scrutinized the comments posted by Bilibili users under this video. The study explored Bilibili users’ reactions and responses to vloggers’ announcement of “stop updating” from five distinct perspectives: (1) attitudes towards the ecosystem; (2) attitudes towards Bilibili; (3) attitudes towards advertising; (4) attitudes towards vloggers; and (5) attitudes towards other users.

At the same time, this study is not without limitations. For instance, it focuses on the specific phenomenon of vloggers announcing “stop updating” on Bilibili. However, Bilibili, as a comprehensive UGC video-sharing platform in contemporary China, has its unique characteristics that set it apart from other online video platforms. Additionally, Bilibili serves as a platform that caters to subcultural communities, which results in differences in its user base and content creators compared to other online video platforms. These differences make the “stop updating” phenomenon on Bilibili relatively unique. Therefore, the findings of this research may not be directly applicable to other online video platforms. Despite the limitation, the study offers insights to examine the timely phenomenon that captures the tensions among the platforms, content creators, and users—a dynamic that is universal to many digital media platforms nowadays.

The objective of this study is to construct a deeper comprehension of the phenomenon of “stop updating” on Bilibili through the reactions and responses of Bilibili users. Firstly, some users have linked the phenomenon of vloggers announcing “stop updating” on Bilibili to the current ecosystem. These users suggest that factors such as influences from other online video platforms, impacts of different video formats, and the current economic recession, which has shaped the current ecosystem, making it relevant to this phenomenon on Bilibili. Secondly, users also hold corresponding attitudes towards Bilibili itself in this “stop updating” phenomenon. These users engage in discussions about Bilibili’s business model in their comments, and some of them express that Bilibili is no longer what it used to be. Thirdly, some Bilibili users have expressed their attitudes towards advertising. Their attitudes are not only directed at different forms of advertisements but also delve into discussions about the nature and content of the advertisements that vloggers accept for profit. Additionally, some Bilibili users have shared their thoughts on Bilibili’s vloggers’ “stop updating”. Finally, some users have directed their comments towards other Bilibili users. These users believe that other Bilibili users are financially challenged and overly demanding. They also suggest that other users should strive to pay for high-quality content created by vloggers. In summary, these diverse responses from Bilibili users shed light on the phenomenon of vloggers announcing “stop updating” on Bilibili from multiple perspectives, sparking in-depth discussions around this occurrence.

With the emergence of the “stop updating” phenomenon among Bilibili’s vloggers, an increasing number of people are paying attention to the operations of online video platforms like Bilibili and the development of content creators on these platforms. However, there has been limited research on this particular phenomenon. Consequently, this study endeavors to make a meaningful contribution to research by delving into the reactions and responses of Bilibili users within the context of this phenomenon.

Firstly, the study echoes an institutional perspective [30] that examines the platform’s influence on cultural production through factors such as multisided markets, platform infrastructure, and governance. In this regard, this study makes senses of Bilibili vloggers “stop updating” phenomenon from the institutional perspective. It highlights the relationships among Bilibili’s platform, content creators, and users, and how these dynamics affect content production, dissemination, and monetization. This effort serves as a demonstration of applying the institutional perspective to Bilibili and the “stop updating” phenomenon, offering valuable insights into the interactions within the platform's ecosystem.

Secondly, ithe findings of this study indicate that content creators on Bilibili are guided by the platform to become monetizers of their content, essentially acting as labor to generate economic value for the platform [9]. The business model of Bilibili and the profit models of content creators on the platform have also garnered significant attention within the context of this phenomenon. Therefore, this study sheds light on the comparison of business models between Bilibili and other online video platforms similar to Bilibili, particularly in aspects related to advertising, sponsorship, and the monetization of content creators. This contributes to a better understanding of the business operations within the sphere of digital content creation.

Thirdly, for Bilibili’s platform operators and decision-makers, this study offers insights into the behaviors of content creators and users on the platform. These insights can aid them in adapting current platform strategies, business models, and governance policies in response to the phenomenon of vloggers announcing “stop updating” on Bilibili. This study also lays a solid foundation for future research to gain insights into the following questions: (1) how platforms respond to the behavior of content creators, and formulate policies to safeguard the rights of both users and content creators; (2) how content creators engage with their audience, attract viewers, and establish their reputation on the platform; and (3) how advertising influences user engagement and brand awareness. Future studies in these areas may employ qualitative in-depth interviews and quantitative methods such as surveys to better understand critical aspects related to platforms, content creators, and users.

References

[1]. Lou X. (2012). Bilibili humorously criticize animation. CBN Weekly. Retrieved from http://finance.sina.com.cn/leadership/mroll/20120427/150111944334.shtml

[2]. Zhou X. (2020). Bilibili’s ‘Wave’ Revelation. Dazhong Daily. Retrieved from http://paper.dzwww.com/dzrb/PDF/20200509/07.pdf

[3]. Wang F. (2019). Bilibili has become one of China’s largest gaming video platforms. Jiemian News. Retrieved from https://www.jiemian.com/article/3254292.html

[4]. Sun C., Zhou D., & Yang T. (2023). Sponsorship disclosure and consumer engagement: Evidence from Bilibili video platform. J Digit Econ, 2, 81–96.

[5]. Wen M. (2020). Targeting the ‘Z Generation,’ Tencent Increases Stake in Bilibili Again. National Business Daily. Retrieved from http://www.nbd.com.cn/articles/2020-02-18/1409212.html

[6]. UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION WASHINGTON, D.C. 20549. (2022). Annual Report on Form 20-F. Retrieved from https://ir.bilibili.com/media/rwafkhml/annual-and-transition-report-of-foreign-private-issuers-sections-13-or-15-d.pdf

[7]. Nan F. (2020). Danmaku: A Unique Screen Phenomenon. GuangMing Daily. Retrieved from https://epaper.gmw.cn/gmrb/html/2020-05/13/nw.D110000gmrb_20200513_2-16.htm

[8]. Fang Z. (2020). Interpreting Online Video ‘Danmaku’ Culture from the Perspective of Youth Subculture. FX361. Retrieved from https://www.fx361.com/page/2020/0513/6655228.shtml

[9]. Wang X. (2022). Popularising Vlogging in China: Bilibili’s Institutional Promotion of Vlogging Culture. Glob Media China, 7(4), 441–462.

[10]. Chen X., Valdovinos Kaye D. B., & Zeng J. (2021). #PositiveEnergy Douyin: Constructing “playful patriotism” in a Chinese short-video application. Chin J Commun, 14(1), 97–117.

[11]. Zhang Z. (2022). The problem analysis and optimization strategy research of the advertising strategy of the Bilibili platform. J Educ Humanit Soc Sci, 5, 99–105.

[12]. Gillespie T. (2010). The politics of ‘platforms’. New Media Soc, 12(3), 347–364.

[13]. Frade J. L. H., Oliveira J. H. C. de, & Giraldi J. de M. E. (2021). Advertising in streaming video: An integrative literature review and research agenda. Telecommun Policy, 45(9), 102186.

[14]. Plantin J. C., Lagoze C., Edwards P. N., & Sandvig C. (2018). Infrastructure studies meet platform studies in the age of Google and Facebook. New Media Soc, 20(1), 293–310.

[15]. SinaTech. (2020). Tudou turned 15 today, but it feels like a ’living dead. SinaTech. Retrieved from https://tech.sina.cn/csj/2020-04-15/doc-iirczymi6380284.d.html

[16]. Craig D., Lin J., & Cunningham S. (2021). Wanghong as Social Media Entertainment in China. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

[17]. Duffy B. E., Poell T., & Nieborg D. B. (2019). Platform Practices in the Cultural Industries: Creativity, Labor, and Citizenship. Soc Media Soc, 5(4), 205630511987967.

[18]. Caplan R., & Gillespie T. (2020). Tiered Governance and Demonetization: The Shifting Terms of Labor and Compensation in the Platform Economy. Soc Media Soc, 6(2), 205630512093663.

[19]. Nieborg D. B., & Poell T. (2018). The platformization of cultural production: Theorizing the contingent cultural commodity. New Media Soc, 20(11), 4275–4292.

[20]. Literat I., & Kligler-Vilenchik N. (2021). How Popular Culture Prompts Youth Collective Political Expression and Cross-Cutting Political Talk on Social Media: A Cross-Platform Analysis. Soc Media Soc, 7(2), 205630512110088.

[21]. Maussen M. (2015). Pillarization. In The Wiley Blackwell Encyclopedia of Race, Ethnicity, and Nationalism (pp. 1–5). John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

[22]. Liu S. K., & Sun S. W. (2021). Research on Bilibili’s Advertising Placement Form. Chuanmei, 11, 53–55.

[23]. Liu S. (2022). Analysis of Bilibili’s Profit Model. Co-Operative Economy & Science, 10, 114–115.

[24]. Lu Y., & Wu Y. (2021). Analysis of the Commercial Profit Model of Subculture Video Websites—Taking Bilibili Danmaku Video Website as an Example. Account Finance, 3, 66–72.

[25]. Cai Z. (2022). Research on the Issues and Countermeasures of Bilibili Uploader Advertising Model. Voice Screen World, 8, 78–80.

[26]. Duan X. (2020). “The Big Women”: A textual analysis of Chinese viewers’ perception toward femvertising vlogs. Glob Media China, 5(3), 228–246.

[27]. McKee A. (2003). Textual Analysis: A Beginner’s Guide (FIRST EDITION). SAGE Publications Ltd.

[28]. Tracy S. J. (2019). Qualitative Research Methods: Collecting Evidence, Crafting Analysis, Communicating Impact (2nd Edition). Wiley-Blackwell.

[29]. Chang Y., Wong S. F., Libaque-Saenz C. F., & Lee H. (2019). e-Commerce Sustainability: The Case of Pinduoduo in China. Sustainability, 11(15), 4053.

[30]. Thomas P., Nieborg D. B., & Duffy B. E. (2021). Platforms and Cultural Production. Wiley.

Cite this article

Zhang,P. (2024). “Stop Updating”: A Textual Analysis of Chinese Viewers Towards the Video of Bilibili Vloggers’ Announcement. Lecture Notes in Education Psychology and Public Media,54,210-230.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Education Innovation and Philosophical Inquiries

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Lou X. (2012). Bilibili humorously criticize animation. CBN Weekly. Retrieved from http://finance.sina.com.cn/leadership/mroll/20120427/150111944334.shtml

[2]. Zhou X. (2020). Bilibili’s ‘Wave’ Revelation. Dazhong Daily. Retrieved from http://paper.dzwww.com/dzrb/PDF/20200509/07.pdf

[3]. Wang F. (2019). Bilibili has become one of China’s largest gaming video platforms. Jiemian News. Retrieved from https://www.jiemian.com/article/3254292.html

[4]. Sun C., Zhou D., & Yang T. (2023). Sponsorship disclosure and consumer engagement: Evidence from Bilibili video platform. J Digit Econ, 2, 81–96.

[5]. Wen M. (2020). Targeting the ‘Z Generation,’ Tencent Increases Stake in Bilibili Again. National Business Daily. Retrieved from http://www.nbd.com.cn/articles/2020-02-18/1409212.html

[6]. UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION WASHINGTON, D.C. 20549. (2022). Annual Report on Form 20-F. Retrieved from https://ir.bilibili.com/media/rwafkhml/annual-and-transition-report-of-foreign-private-issuers-sections-13-or-15-d.pdf

[7]. Nan F. (2020). Danmaku: A Unique Screen Phenomenon. GuangMing Daily. Retrieved from https://epaper.gmw.cn/gmrb/html/2020-05/13/nw.D110000gmrb_20200513_2-16.htm

[8]. Fang Z. (2020). Interpreting Online Video ‘Danmaku’ Culture from the Perspective of Youth Subculture. FX361. Retrieved from https://www.fx361.com/page/2020/0513/6655228.shtml

[9]. Wang X. (2022). Popularising Vlogging in China: Bilibili’s Institutional Promotion of Vlogging Culture. Glob Media China, 7(4), 441–462.

[10]. Chen X., Valdovinos Kaye D. B., & Zeng J. (2021). #PositiveEnergy Douyin: Constructing “playful patriotism” in a Chinese short-video application. Chin J Commun, 14(1), 97–117.

[11]. Zhang Z. (2022). The problem analysis and optimization strategy research of the advertising strategy of the Bilibili platform. J Educ Humanit Soc Sci, 5, 99–105.

[12]. Gillespie T. (2010). The politics of ‘platforms’. New Media Soc, 12(3), 347–364.

[13]. Frade J. L. H., Oliveira J. H. C. de, & Giraldi J. de M. E. (2021). Advertising in streaming video: An integrative literature review and research agenda. Telecommun Policy, 45(9), 102186.

[14]. Plantin J. C., Lagoze C., Edwards P. N., & Sandvig C. (2018). Infrastructure studies meet platform studies in the age of Google and Facebook. New Media Soc, 20(1), 293–310.

[15]. SinaTech. (2020). Tudou turned 15 today, but it feels like a ’living dead. SinaTech. Retrieved from https://tech.sina.cn/csj/2020-04-15/doc-iirczymi6380284.d.html

[16]. Craig D., Lin J., & Cunningham S. (2021). Wanghong as Social Media Entertainment in China. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

[17]. Duffy B. E., Poell T., & Nieborg D. B. (2019). Platform Practices in the Cultural Industries: Creativity, Labor, and Citizenship. Soc Media Soc, 5(4), 205630511987967.

[18]. Caplan R., & Gillespie T. (2020). Tiered Governance and Demonetization: The Shifting Terms of Labor and Compensation in the Platform Economy. Soc Media Soc, 6(2), 205630512093663.

[19]. Nieborg D. B., & Poell T. (2018). The platformization of cultural production: Theorizing the contingent cultural commodity. New Media Soc, 20(11), 4275–4292.

[20]. Literat I., & Kligler-Vilenchik N. (2021). How Popular Culture Prompts Youth Collective Political Expression and Cross-Cutting Political Talk on Social Media: A Cross-Platform Analysis. Soc Media Soc, 7(2), 205630512110088.

[21]. Maussen M. (2015). Pillarization. In The Wiley Blackwell Encyclopedia of Race, Ethnicity, and Nationalism (pp. 1–5). John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

[22]. Liu S. K., & Sun S. W. (2021). Research on Bilibili’s Advertising Placement Form. Chuanmei, 11, 53–55.

[23]. Liu S. (2022). Analysis of Bilibili’s Profit Model. Co-Operative Economy & Science, 10, 114–115.

[24]. Lu Y., & Wu Y. (2021). Analysis of the Commercial Profit Model of Subculture Video Websites—Taking Bilibili Danmaku Video Website as an Example. Account Finance, 3, 66–72.

[25]. Cai Z. (2022). Research on the Issues and Countermeasures of Bilibili Uploader Advertising Model. Voice Screen World, 8, 78–80.

[26]. Duan X. (2020). “The Big Women”: A textual analysis of Chinese viewers’ perception toward femvertising vlogs. Glob Media China, 5(3), 228–246.

[27]. McKee A. (2003). Textual Analysis: A Beginner’s Guide (FIRST EDITION). SAGE Publications Ltd.

[28]. Tracy S. J. (2019). Qualitative Research Methods: Collecting Evidence, Crafting Analysis, Communicating Impact (2nd Edition). Wiley-Blackwell.

[29]. Chang Y., Wong S. F., Libaque-Saenz C. F., & Lee H. (2019). e-Commerce Sustainability: The Case of Pinduoduo in China. Sustainability, 11(15), 4053.

[30]. Thomas P., Nieborg D. B., & Duffy B. E. (2021). Platforms and Cultural Production. Wiley.