1. Introduction

The representation of masculinity and homosociality in Western cinema is constantly evolving, being constructed and deconstructed over time. In the Western cinema represented by Hollywood, the traditional idealized masculinity has long been depicted as toughness, stoicism, physical violence and freedom of action. Until the 1980s, masculinity in Western cinema presented a spectacle of male machismo centered around violence, aggression and strength. In the 1990s, masculinity on screen became gentler, more uncertain, and more expressive of male emotions, also prompting a deeper reflection on white masculinity [1].

The construction of masculinity is inseparable from the network and background of male social relations. Masculinity in genres like war films, action films and Westerns is especially constructed in male partnerships and hierarchical male groups [2]. Homosociality is often presented as comradeship, frequently occurring against the background like taverns, ranches, and military settings. While black masculinity on screen has long been relegated to supporting roles historically, the emergence of action films as an independent genre in the 1980s paved the way for figures of color to take center stage, albeit within certain limitations, thus challenging the prevailing conventions of white masculinity in Hollywood films [3].

In the 21st century, Western cinema has undergone a more diversified and in-depth exploration of masculinity and homosociality, questioning, challenging and subverting those that were long constructed on screen in the past. The film Close, selected for analysis in this paper, takes the modern society of Belgium as its background, and tells a story of the collapse of the close friendship between Leo and Remi, two 13-year-old boys [4]. Due to the suspicions about their relationship and homophobic bullying from their classmates after entering middle school, Leo chooses to gradually distance himself from Remi, which ultimately leads to the tragic suicide of Remi. Subsequently, Leo grapples with the weight of accountability and the sorrow of losing Remi, finding relief only after approaching and confessing the truth to Remi's mother. Through an analysis of the masculinity and homosociality depicted in this recent film, this paper seeks to explore the dynamics of masculinities and homosocial relationships, as well as the gender structures that underlie them. It aims to reveal both the successes and shortcomings of its representation of masculinity and homosociality, and offer prospects for their potential portrayal in future cinema.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Definition and Discussion of Masculinity

The definition of masculinity has evolved from an essentialist construction to an anti-essentialist deconstruction. Research on masculinity in the 1980s often responded to the notion that masculinity is innate or essential, or in the social sciences, to sex role theory, which views masculinity as a stable, uniform, normative configuration [5]. Since then, scholars of masculinity have gradually become skeptical of this essentialist view, focusing on the diversity of masculinity, particularly through the study of its historical changes [6,7]. The de-essentialization of masculinity became the prevailing theme in masculinity studies in the 1990s, with R.W. Connell's Masculinities standing as one of the most influential theoretical works in the history of masculinity studies, largely due to his reference to Antonio Gramsci's hegemonic theory [8]. He introduced the concept of hegemonic masculinity in a groundbreaking way and elucidated the relationship between masculinities by categorizing them into four groups — hegemony, subordination, complicity, and marginalization.

In Cornell's Masculinities, hegemonic masculinity is defined as "the configuration of gender practice which embodies the currently accepted answer to the problem of the legitimacy of patriarchy, which guarantees (or is taken to guarantee) the dominant position of men and the subordination of women" [8]. However, few men embody this masculine ideal, and most men become complicit in patriarchy and hegemonic masculinity in order to gain patriarchal benefits, while subordinated and marginalized men often descend into scapegoats for male domination. The subordination of homosexual masculinity is particularly evident, and heterosexual men displaying femininity are also marginalized from the accepted norm of masculinity [8]. In marginalized masculinity, Connell introduces additional structures such as class and race to the intersectionality of gender, with lower-class and men of color frequently experiencing marginalization. Connell emphasizes that these masculinities are not fixed personality types, but rather configurations of gender practices that emerge from shifting relationship structures [8].

Connell's theory of masculinities has been widely used as a theoretical model, but it has also faced numerous criticisms. Yang summarized the academic criticisms of Connell's theory, pointing out that hegemonic masculinity is ambiguous in concept, with multiple and even contradictory definitions in his works, and tends to neglect the potential positive effects it may have [9]. This oversight can lead to an overemphasis on its negative impact. In Gramsci's theory, hegemony carries the potential for both retrogression and progress. Connell, however, tends to overemphasize its negative interpretation in his application of the concept, believing that it always legitimates patriarchy. Yang offers an alternative understanding of hegemonic masculinity by revisiting Gramsci's hegemonic theory. He argues that hegemonic masculinity is not defined by established masculine qualities, but rather through a mechanism of domination, which is "force accompanied by consent" [9]. This reconceptualization places greater emphasis on the relationships between men and presents a positive interpretation of hegemonic masculinity, along with the potential for social change.

Similarly, in the process of analyzing the representation of masculinity in the film Close, this paper will focus on the relationships between men, i.e., homosociality, in order to explore the mechanisms of masculine interaction. As a medium for presenting and shaping masculinity, cinema plays a significant role in constructing positive hegemonic masculinity. The diversity of masculinity itself constitutes an important asset for social revolution, with the construction of positive hegemony being a powerful strategy. With a more diverse and inclusive portrayal of masculinity on screen, and through the incorporation of more positive and rich survival narratives of subordinated and marginalized males, an anti-sexist, anti-heterosexist, diverse, and inclusive masculinity may one day achieve hegemony.

2.2. Definition and Discussion of Homosociality

The concept of homosociality originated in Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick's Between Men and became a widely used term in gender studies [10]. It refers to relationships between individuals of the same sex, excluding romantic and sexual aspects. Homosociality has often been interpreted in the past as a mechanism by which men maintain male hegemony and patriarchy through their relationships with other men [11]. Under this understanding, homosociality acts as an exclusion mechanism, reinforcing traditional gender norms and gender-based hierarchies, as well as perpetuating the subordination of non-male and non-heterosexual individuals. The complexity of homosociality has been recognized by more and more scholars nowadays. That is, it is not only capable of defending hegemonic masculinity, but also has the potential to deconstruct and rebuild existing gender power structures [12]. Through a distinction between hierarchical homosociality and horizontal homosociality, Hammaren & Johansson deconstruct the structuralist understanding of homosociality [13]. In their interpretation, hierarchical homosociality refers to the previous understanding of homosociality in a structuralist way: a mechanism to strengthen power and defend hegemony through the close bonding between individuals of the same sex; horizontal homosociality refers to an inclusive relationship between people of the same sex, often based on emotional closeness, intimacy, and non-profitable friendship [13].

The conceptualization of horizontal homosociality makes a reconfiguration of hegemony possible, which includes a transition of intimacy, gender and power relations [12]. The distinction between hierarchical and horizontal homosociality also deconstructs the structuralist understanding of the relationship between hegemonic masculinity and homosociality. Homosociality is no longer simply perceived as a mechanism to maintain hegemonic masculinity and patriarchy, but is seen as having the potential to disintegrate them.

3. Methodology

This paper will employ textual analysis and formal analysis, including cinematography, mise-en-scene, etc., to analyze the representation of masculinity and homosociality in the film Close. Theories of masculinity and homosociality will be applied for elaboration. By incorporating a focus on homosociality, as a social relation that connects individuals, it can shift the analysis of masculinities from static types to dynamic relationships, aiming to uncover how the power structure among men operates and how the gender structure is maintained. Based on the deconstructive interpretation of masculinity and homosociality, this paper will provide implications for the future representation of films.

4. Discussion

4.1. Masculinity Representation of Male Characters

4.1.1. Leo: In Between Subordination and Complicity

Due to Leo and Remi's unusual closeness, several boys in the class physically and verbally bully Leo, placing him in a subordinated masculine position at the beginning of the film. The physical bullying of Leo creates inequality in male relationships through aggressive and violent interactions. Through homophobic and misogynistic discourse in verbal bullying, the bullies put Leo in a subordinated and feminine position, thereby establishing a hegemonic relationship in which the bullies exhibit hegemonic masculinity, while Leo is relegated to a subordinated masculine role. Through misogynistic remarks, Leo is endowed with "inferior" gender qualities similar to femininity by the bullies. This provides a legitimizing discursive justification for gender inequality, forming a cultural ascendancy in which hegemonic masculinity and subordinate masculinity correspond to superiority/inferiority respectively, which also implies policing/being policed.

Leo took a negative reflection and consented in the face of the situational hegemony. According to Yang, Gramsci's hegemony is a form of conscious domination that involves positive consent [9]. Hegemony relies on the knowledge and willingness of the dominated to participate in the conquest [14]. In other words, men with subordinated masculinity, even if aware of their subordination, may still consent to the concessions they receive in order to benefit from patriarchy. However, the establishment of hegemony is not necessarily based on positive consent from men in subordinated positions, but rather, on negative consent. Leo does not actively seek subordination but is passively placed in a subordinated masculine position through the bullies' discursive and physical practices. By passively giving consent and joining the mainstream group, Leo conforms to the social expectation of masculinity and gains recognition from other males.

Leo gradually transitions from a position of subordinated masculinity to complicit masculinity. Faced with the pressure of homophobic discourse, subordinated masculinity becomes something Leo endeavors to get rid of. The most effective means of doing so is by distancing himself from Remi and joining a group that best embodies normal and legitimate masculinity. In the film, one of the most noteworthy portrayals is the process of Leo joining ice hockey through his friendship with Baptiste, a classmate who excels at the sport. According to Tjønndal, sports are often viewed as domains of orthodox masculinity, and ice hockey, being a violence-centered hyper-masculine sport, particularly exemplifies the dominant traditional norms of masculinity [15]. Through a documentary-like way of shooting, the aggression, violence and competitiveness inherent in ice hockey are visualized through costume, body movement, impact and injury, illustrating the orthodox masculinity constructed on Leo by the sport.

After Leo participates in ice hockey, an interesting scene unfolds: Leo becomes a member of a group engaged in physical violence. He and other boys surround a boy in the locker room and playfully snap at him with their clothes. The medium shot of Leo's thin upper torso without much muscle sharply contrasts with the flapping clothes (Figure 1). Though presented in a playful manner, we can still discern Leo's reversal in the dominant-subordinate relationship. Leo was once the target and victim of homophobic physical violence, but now he is the perpetrator of physical violence within an ice hockey boys' group. Just as Cornell emphasized, hegemonic masculinity, subordinated masculinity and other forms of masculinity are not fixed personality types, but rather, configurations of gender practices in specific situations within evolving relationship structures [8].

Figure 1: Leo and the other boys playfully snapping a boy on the back with their clothes in the locker room [4]

When Leo makes reflexivity and decides to join the hegemonic male group characterized by hyper-masculine sports, physical violence and aggression, he shifts from a previously subordinated position. Through his participation and involvement in physically aggressive behavior towards other males, Leo aligns himself with the hegemonic practice and the construction of hegemony. He evolves from a victim of hegemonic masculinity into an accomplice, simultaneously transitioning from subordinated masculinity to complicit masculinity. Leo reproduces and perpetuates the structure of these masculine relationships by participating in the social practice of masculine physical violence. Through physical violence, the culturally dominant means of shaping male relationships, which initially placed Leo in a subordinated position relative to other boys, Leo participates in the construction of a dominant masculinity within the school.

4.1.2. Remi: Persistence and Tragedy of Subordinated Masculinity

Like Leo at the beginning of the film, Remi is also placed in a subordinated position due to his intimacy with Leo and not fitting into mainstream groups. But unlike Leo, Remi doesn't change his thoughts and behavior because of classmates' suspicions about their relationship and homophobic comments. When some girls in his class ask Leo and Remi if they are a couple, Remi smiles with a hint of excitement as he sees it as proof of their close friendship. In the face of other boys' insulting remarks, he chooses to ignore them. Remi does not show fear of being perceived as homosexual or effeminate and is not eager to affirm his heterosexuality and masculine identities (although we are not sure about his sexual orientation). He refuses to change and tries to retain their friendship, but he is rejected due to his deviation from dominant norms. The insistence on subordinated masculinity ultimately leads to Remi's tragedy, because even though he tries his best to retain their friendship, Leo's estrangement, step by step, brings the final blow.

However, the audience's subconscious, brought about by such a tragedy, contains the possibility of alerting and preventing; that is, embodying and presenting feminized or gay masculinity or developing intimate friendships with the same sex may lead to the collapse of relationships and even one's own destruction. The director, Lukas Dhont, did not initially intend to create a tragedy for the film [16]. However, given the director's intention to express Leo's awareness of accountability and guilt, a fatal ending for Remi seems to be the only solution. Without Remi's death, it appears that Leo would have had little opportunity or possibility for awareness and change. Additionally, if we overemphasize the illogic of Remi's death, we may weaken people's awareness of the actual probability of such events, and thus neglect the seriousness of the problem. Nonetheless, we still need to reflect on the representation of subordinated masculinity ending in tragedy. Even though this tragic presentation can reveal a common social problem and inspire the audience's reflection, this negative representation still does not tell us how people like Remi should continue to be themselves and survive in society, nor does it tell us how male close friendships should overcome the malice of their surroundings and maintain their purity. These are the possibilities that screen representation should further explore.

4.1.3. The Bullies: Hegemonic Masculinity Through Discursive Persuasion

The hegemonic masculinity of the bullies is achieved in the film primarily through homophobic and misogynistic discourse: "My name is Leo and I'm a fag." "Leo? You look a little tense. Do you have your period or something?" Through "fag" discourse, boys discipline each other, solidify their relationships, and maintain their masculine identity [17]. Through misogynistic discourse, bullies exclude Leo from the circle of legitimate masculinity by assigning him to femininity, a trait that equates to an inferior status.

Hegemonic masculinity is mainly achieved through discursive persuasion, encouraging all people to agree and embody the inequality between men and women, between masculinities and femininities, and among masculinities, in order to obtain cultural ascendancy and legitimate patriarchal relations [18]. In Leo's second encounter with verbal bullying, the bully says, "Leo? You look a little tense. Do you have your period or something?" Leo's friend Sekou immediately laughs and says, "Shut your trap!" Leo, Sekou, and the rest of the crew laughed. Baptiste then says, "Come on, that's not funny." But the bully insists, saying, "Yes it is." Baptiste replies, "It's not." The bully repeats, "Yes, it is. They laughed." Here, the bully uses "They laughed" to justify the legitimacy of the misogynistic discourse in verbal bullying, implying that everyone agrees it's a funny joke in an attempt to convince the objector Baptiste to join in the cultural ascendancy of consent and embodiment of unequal gender relations. In this dispute, there is a stark contrast between hegemonic masculinity and positive masculinity. Hegemonic masculinity, embodied by the bully, attempts to legitimate unequal gender/masculinities relations. In contrast, positive masculinity, embodied by Baptiste, seeks to legitimate egalitarian gender/masculinities relations.

It's worth noting that in the verbal bullying interaction, the homophobic and misogynistic discourse bullies use to place Leo in a feminized and subordinated position, producing an unequal masculine and feminine relationship, was reproduced in the discourse of counter-bullies. A girl's voice in the peer group emerges after Leo is bullied: "They're pansies anyway. Why do they find the need to do that?" Misogyny and homophobia are hegemonic in the way that they legitimate gender inequality, while the anti-hegemonic discourse is compelled to use hegemonic discourse. This emphasized reuse of discourse fails to disengage from the patriarchal framework of gender inequality, thereby failing to counter hegemony, but rather reproducing the culture of gender inequality at the level of discourse.

However, the establishment of hegemony is not solely due to the interactive homophobic bullying of individuals, but is deeply rooted in the systems and structures of institutions. This is often invisible and not easy to detect, while the presentation of the film precisely weakens this point: the film does not show the school's intervention and resolution of homophobic bullying, nor does it depict direct gender and sexuality education in the school. The school's shaping of gender expression is hidden in sports and such, but behind it lie a series of systems and structures including teaching practices, subject structures and other bureaucratic procedures [19]. According to Cornell, hegemony can be established only when there is some consistency between the ideals of culture and the power of institutions, which may be individual or collective [8]. That is to say, the legitimization of patriarchy and the consistency of school institutional power establish authority for hegemonic masculinity. Pascoe also argues that the focus on homophobic bullying directs attention towards the interactions on an individual level, rather than the school's mechanism on a systematic level [19]. The film's overemphasis on the individual interactive factors that drive Leo to distance himself from Remi also obscures and conceals the structural and systemic inequalities in gender and gender expression.

4.1.4. Baptiste and Sekou: Positive Masculinity and Intersectional Perspective

Dominant masculinity and dominating masculinity are not necessarily hegemonic in the way that legitimates gender inequality, but they have the potential to be positive masculinity in the way that legitimates egalitarian gender relations. From the interaction between Baptiste and his peers, we can see that he embodies dominant masculinity while also displaying dominating masculinity. According to Messerschmidt, dominant masculinity refers to the most common, popular and widespread types of masculinities in a certain setting [18]. In this sense, Baptiste is a sporty boy, fond of sports such as ice hockey, which is consistent with the most common and widespread image of sports boys in various school scenes in the film. They are always engaged in sports, with football and ice hockey being the most prominent, and they frequently discuss players, games, and the like. (In contrast, Leo and Remi are initially observers rather than participants, with Leo eager to join and Remi simply looking on, seemingly uninterested). Dominating masculinity, which Baptiste also displays, refers to masculinity characterized by commanding and controlling people or events in interaction [18]. Through the composition, we can observe the dominating masculinity of Baptiste. He is always positioned at the center of the frame, surrounded by other boys and girls (see Figure 2); in a scene of playing football, Baptiste's words, "I'm in the middle," also emphasize his central role in occupying a central position in the composition (see Figure 3). In one scene, Baptiste is encircled by his peers, recounting an experience he had on the highway. Suddenly, a girl beside him exclaims, "Nobody cares!" Baptiste points to another girl and says, "She's the one asking! Stop yelling!" In another scene, several girls tease a boy lying on the lawn with weeds, and Baptiste says, "Stop it, girls. Let them sleep." Baptiste also attempts to intervene when Leo is verbally bullied for a second time. It can be seen that the dominant masculinity and dominating masculinity displayed by Baptiste play a role in achieving respect for both males and females, thus representing a form of positive masculinity that seeks to legitimate equality between men and women, between masculinity and femininity, and among masculinities in a non-violent manner.

Figure 2: Baptiste surrounded by his peers in conversation [4]

Figure 3: Baptiste playing football with the boys [4]

In Cornell's theory, race, class, and other structures are taken into account to theorize masculinities from an intersectional perspective, and the masculinity of colored people and the lower class is often marginalized [8]. In the film, we see that one of the boys involved in verbal and physical bullying is Jules, who is black. This demonstrates that when black males engage in the discourse and practices that legitimize the unequal relationship among genders and among masculinities, they do not present marginalized masculinity solely because of their race but rather embody hegemonic masculinity. Simultaneously, we observe Sekou, another black boy who often hangs out with Baptiste and Leo, making a retort, though not in a serious manner, to Leo's second encounter with verbal bullying. This serves as a voice of color attempting to challenge the legalization of unequal relationships among genders and among masculinities and, therefore, exhibits an underlying tendency towards positive masculinity. Both black characters illustrate that marginalized masculinity, hegemonic masculinity, and positive masculinity are all configurations of masculinity produced in specific practices.

4.1.5. Leo's Father and Remi's Father: Challenging the Norm

In addition to the two male protagonists and their classmates, there are also two notable male characters in the film: Leo's father and Remi's father. Although the provided footage is not sufficient, making it difficult to grasp the full dimensions of these two fathers' masculinity, two scenes that leave the deepest impression on us hold some significance in naturalizing the representation of nontraditional masculinity in the film.

After Remi's death, the two families have dinner at Leo's house. When they hear Leo's brother's plans for the future, Remi's father thinks of Remi and cries at the table, while Remi's mother acts stoically, gets up and walks out of the house. The stereotyped portrayal of the father image in cinema is often tough and enduring, but Close shows us the real, natural and challenging side. It shows the challenge to legitimate masculinity and the standardization of heterosexuality and gives legitimacy to males' explicit emotions.

As for Leo's father, there is also a scene in the film where Leo cries while getting a plaster bandage in the hospital after being injured in an ice hockey competition. Instead of saying, "Don't cry, be strong", Leo's father comes, hugs Leo, and comforts him with touching and kissing. This action forms a contrast with the strong and muscular body image he typically presents. It further deepens the challenge to the representation of traditional idealized masculinity and the legitimate heteronormativity.

4.2. Homosociality Among Male Characters

4.2.1. Horizontal Homosociality Between Leo and Remi

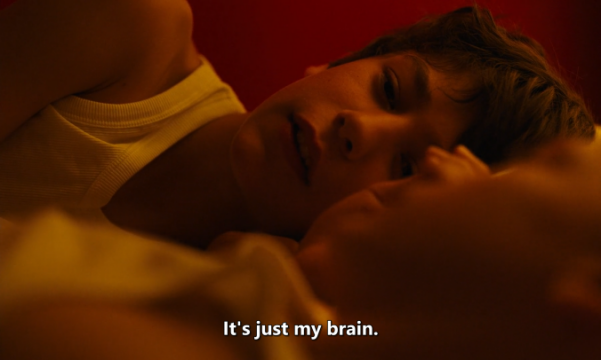

In the film's delicate depiction at the beginning, Leo and Remi's friendship takes on a horizontal homosociality centered on intimacy. Their physical closeness is portrayed through numerous close-up shots (e.g., Figure 4), and their emotional closeness is enhanced with music and warm tones (e.g., Figure 5 & Figure 6). The relationship between Leo and Remi is based on emotional closeness, intimacy, and a non-profitable form of friendship, which can be seen as horizontal homosociality. In a sequence illustrating their intimacy, Leo tells Remi a story to help him relax because Remi feels worried and can't fall asleep. The warm yellow tones of the whole image create a safe environment to show their emotional and physical closeness. Additionally, the balanced composition of the frame reflects an equal, intimate, non-erotic friendship between them, with no hierarchy (Figure 7).

Figure 4: Leo leaning on Remi's shoulder in the classroom [4]

Figure 5: Leo watching Remi perform in an orchestra, with the soothing background music played by the orchestra [4]

Figure 6: Remi confiding his worries to Leo [4]

Figure 7: Leo and Remi sleeping in a bed at Remi's house [4]

However, in male social circles, men generally do not develop emotional relationships with each other but express and maintain hegemonic masculinity through withholding expressions of intimacy [20]. Even when individuals violate norms of emotional indifference, they are repressed by society's perception of "appropriate" masculinity. Because the concepts of love and intimacy are feminized, and feminization implies subordination, horizontal homosociality based on intimacy becomes the object of scrutiny, perceived as anti-heteronormativity, and is excluded from the orthodox male social circle [21]. In contrast, women's intimacy is considered an expression of friendship and heterosexuality, and they kiss, hold hands, and hug without worrying about being considered homosexual. As Close shows, girls who question Leo and Remi's relationship can make intimate gestures on the spot to prove their friendship without worrying about being suspected of homosexuality, while Leo struggles to affirm his heterosexual identity and non-erotic relationship with Remi by arguing that they never hold hands or kiss.

Additionally, an incident just before Leo and Remi's friendship completely breaks down also has some implications about emotional detachment. After Leo leaves Remi to go to school with other boys, Remi's fragile tears are in sharp contrast to Leo's cold statement to Remi, "lt's nothing, Remi. Stop crying." We can observe the changes in Leo's emotional withdrawal as he tries to conform to masculine norms and gain the recognition of the orthodox male social circle. The expression of emotion represents vulnerability and a loss of control, while the opposite emotional detachment represents strength and mastery of control, constituting a means to maintain gender hierarchy [22].

Notably, there's still a subtle imbalance of power existing between Leo and Remi. In the sequence, which it mainly uses close-up shots to show the nuanced reactions of Leo and Remi facing suspicion from their female classmates, we can see that Remi remains silent throughout the sequence while Leo fiercely disputes it. This means that it is Leo who has a say in defining their relationship and declaring it to others. We can also observe that it is Leo who dominates their friendship through their interactive activities. For instance, in the first sequence of the whole film, they are playing war games led by Leo. This imbalance of power can also be observed in Leo's detachment and Remi's attempts to maintain their friendship.

Hence, although the closeness and intimacy of their friendship can be seen as horizontal homosociality, the subtle power imbalance within their relationship can be viewed as hierarchical. This is also a contributing factor to the eventual collapse of their friendship.

4.2.2. Hierarchical Homosociality Between Leo and the Bullies

The hierarchical homosociality between Leo and the bullies is mainly achieved through physical violence and verbal bullying, which includes homophobia and misogynistic slurs, forming a hegemonic relationship. In this form of homosociality, one side holds a position of authority or seniority over the other, leading to a hierarchical structure within the relationship. Homophobia is a significant factor that influences their homosocial interactions. The fear of being associated with homosexuality can lead to the policing of male behavior within homosocial spaces, suppressing emotional expression and intimacy among men and simultaneously forming a gender hierarchy.

However, once Leo fits into the mainstream group of boys by joining the sport of football, the homosociality between Leo and the bullies also exhibits a horizontal tendency, demonstrated by Leo participating in football with the male mainstream group, which includes the bullies Salva and Jules, and cycling to school with boys including Jules. Nevertheless, this horizontal tendency is not absolute. The small talk centered around football serves as the means of mutual recognition among the boys in the clique. However, Leo never contributes to the discussions but rather acts as an observer and echoer. This also implies that Leo has no voice and is not the dominant figure in the mainstream group. Additionally, there are more or less competitive elements in male same-sex interactions such as football, ice hockey, and racing bikes, all of which Leo participates in. Competition, as a means to perpetuate dominance, fosters the hierarchical dynamic within the relationship [20]. Certainly, there are also cooperative interactions that promote symmetrical relationships in these sports, but competition still remains the primary feature in these activities.

Noticeably, after Leo's integration into the mainstream group and the death of Remi, he feels a loss of something precious: intimate friendship. This kind of friendship is based on a thorough knowledge of the other person, a fondness and appreciation for each other's character and personality, and the expression of one another's emotions. The majority of male friendships are not built on the qualities mentioned above but on surface-level common activities or interests, or benefits. This kind of friendship, based on what Aristotle calls usefulness or pleasure, is not an intimate friendship [23]. The friendship between Leo and Baptiste is one based solely on shared activities like ice hockey and games, with no exchange of emotion or thoughts (this can be clearly seen in the contrast between Leo's interactions with Baptiste and with Remi). The absence of such an intimate friendship is the result of the socialization of males' emotional detachment and can ultimately lead to a loss of ability to understand one's feelings and a decrease in happiness in life.

To sum up, we can see that horizontal homosociality between Leo and Remi and hierarchical homosociality between Leo and the bullies are not absolute, stable or fixed but rather mixed and subject to change. Both horizontal homosociality and hierarchical homosociality have certain hierarchical and horizontal components or tendencies, respectively, and are constructed through dynamic concrete behaviors.

4.3. Discussion on the Interplay Between Masculinity and Homosociality

Through the analysis of masculinity and homosociality provided above, it becomes apparent that discussing masculinity in isolation from homosociality, and vice versa, is challenging. In reality, they are closely intertwined and mutually influential.

Masculinity is constructed within a relational framework. This means that different forms of masculinities are all established in social relationships, especially within homosocial contexts. Within these interactions, the hegemonic position of one and the subordinate position of the other can be asserted and realized. Homosocial spaces often offer opportunities for men to assert and validate certain forms of masculinity while simultaneously potentially subordinating or marginalizing others. This dynamic is evident in the hierarchical homosociality between Leo and the bullies, where hegemonic masculinity is affirmed, leaving Leo and Remi in a subordinate position.

Furthermore, the dynamics within these homosocial spaces can be influenced by the prevailing societal notions of masculinity. In this film, for instance, the dominant conception of masculinity contributes to the deterioration of the homosociality between Leo and Remi while reinforcing the homosociality between Leo and his other peers. Moreover, shifts in the dynamics of masculinity can lead to corresponding changes in homosociality. As seen when Leo undergoes a transformation in his expression of masculinity towards a complicit form and integrates into the mainstream group, the homosociality between Leo and the bullies gradually transitions from a hierarchical to a more horizontal tendency.

5. Conclusion

There is no doubt that this film contributes a diverse and socially critical perspective to Western cinema in representing masculinity and homosociality. In addition to revealing different masculinities and their power structures, as well as exploring the interplay between masculinity and homosociality, the film also endeavors to naturalize unconventional masculinities. This naturalized representation presents a powerful challenge to stereotypes and normative notions of masculinity.

It is worth noting that the film depicts the tragic fate of subordinated masculinity: suicide. While its intention is to shed light on this cruel social reality, urgently demanding reflection and change, it still exerts a significant subconscious impact on the spectators in front of the screen. This implies that subordinated masculinity is given a negative ending without offering insights into how it can navigate society, which is an aspect that future films should explore further in the representation of masculinity. The screen representation of non-hegemonic masculinity requires a more positive exploration, fully showcasing the protagonists' agency, which has implications for the future portrayal of males in Western cinema.

Beyond that, the reflection and reconstruction of male same-sex intimacy is what the film fails to present to the audience. Although the director employs the imagery of flowers reopening in the field at the end of the film to symbolize hope and the potential for a new beginning in Leo's life, we are left in the dark about whether Leo has reflected on and made positive progress in his understanding of masculinity and his relationships with his friends. In the film, we observe his yearning for his friendship with Remi after Remi's passing. This is evident in the second half of the film when Leo shares a bed with his brother (see Figure 8, a scene reminiscent of his shared bed with Remi, compared with Figure 7, the difference being that Leo is now the one being embraced); Leo resting on his brother's shoulder (Figure 9, mirroring his posture with Remi, in contrast to Figure 4); and Leo spending the night at Baptiste's house, his new ice hockey friend (Figure 10, a perspective akin to Leo's sleepover at Remi's house, compared to Figure 11), and so forth. All of these instances reveal Leo's longing for the intimate friendship with Remi that he has lost and his desire for physical and emotional intimacy in friendship. However, we see that his close relationship with Remi cannot be redeemed or replaced by any other connection. Whether Leo will ever form a similar bond with someone of the same sex remains an open question for the audience, and the film may implicitly convey a negative answer. The reflection and reconstruction of intimate relationships after grappling with responsibility and guilt is a facet the film fails to delve into.

Figure 8: Leo turning to his brother in his sleep and expressing how much he misses Remi after his passing [4]

Figure 9: Leo leaning on his brother's shoulder as they head home [4]

Figure 10: Leo gazing thoughtfully at Baptiste when he spends the night at his house, likely thinking about Remi [4]

Figure 11: Leo noticing that Remi is having trouble falling asleep [4]

Positive hegemony remains a central strategy in contemporary reform efforts [24]. Cinema can serve as an agency for representing and constructing positive and diverse masculinity and homosociality. By portraying and naturalizing aspects of male homosociality, such as intimacy, non-misogynistic and anti-homophobic behaviors, the film can become a platform for deconstructing and reconstructing gender structure. The tragic narrative of Close leaves the audience without a clear view of Leo's transformation. Will Leo, after grappling with guilt and responsibility, take the initiative to rebuild intimate friendships with others, having lost the precious intimate friendship with Remi? Is it possible for the film to attempt a narrative depicting how Leo and Remi distance themselves from or challenge the existing structure of male relationships and engage in an alternative, non-violent, positive masculinity, trying to construct an egalitarian relational structure? Perhaps, having revealed the failure of horizontal homosociality, it is time for cinema to present a possible narrative that showcases horizontal homosociality triumphing over hierarchical homosociality. This might encompass the naturalization of same-sex intimacy, the resolution of the crisis of same-sex intimacy, the resistance to homophobic and misogynistic behavior, school education on non-heteronormativity, and so on. Just as Haywood et al. argue, articulating intimacy and emotional closeness with masculinity can point towards a potential reconfiguration of hegemonic masculinity [12]. As these representations and constructions become more prevalent in cinema, it will be more likely that homophobia, heteronormativity, and gender hierarchies will break down, and a form of masculinity that is non-violent, positive, non-homophobic, and supports gender equality may one day achieve hegemony. Hierarchical homosociality serves as a space for asserting and solidifying hegemony, while horizontal homosociality, if more visible and accepted, could potentially reconfigure and construct a new type of hegemonic ideal, thereby deconstructing the hierarchical gender structure and heteronormativity. This necessitates further theoretical and practical exploration, with cinema's role being indispensable.

References

[1]. Nelmes, J. (2012) Gender and Film. Jill, N. (Ed.), Introduction to Film Studies. Routledge, New York. pp.262–297.

[2]. Tasker, Y.(2017) Contested Masculinities: the Action Film, the War Film, and the Western. In: Kristin, L. H., Dijana J., E. Ann K., and Patrice P. (Eds.), The Routledge Companion to Cinema and Gender. Routledge, New York. pp.111–120.

[3]. Purse, L. (2011) Contemporary Action Cinema. Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh.

[4]. Dhont L. (2022) Close. Diaphana Films, France.

[5]. Reeser, T. W. (2015) Concepts of Masculinity and Masculinity Studies. In: Stefan, H. (Ed.), Configuring Masculinity in Theory and Literary Practice. Brill, Leiden. pp. 11–38.

[6]. Brod, H. (1987) The Making of Masculinities: The New Men's Studies. Allen & Unwin, Boston.

[7]. Kimmel, M. (1996) Manhood in America: A Cultural History. Free Press, New York.

[8]. Connell, R. W. (1995) Masculinities. University of California Press, Berkeley.

[9]. Yang, Y. (2020) What's Hegemonic about Hegemonic Masculinity? Legitimation and Beyond. Sociological Theory, 38(4): 318–333.

[10]. Sedgwick, E. K. (1985) Between Men: English Literature and Male Homosocial Desire. Columbia University Press, New York.

[11]. Bird, S.R. (1996) Welcome to the Men's Club: Homosociality and the Maintenance of Bonding, and Male Friendship. Men and Masculinities, 15(3): 249–270.

[12]. Haywood, C., Johansson, T., Hammaren, N., Ottemo, A., Herz, M. (2018). The Conundrum of Masculinities: Hegemony, Homosociality, Homophobia and Heteronormativity. Routledge, New York.

[13]. Hammaren, N., Johansson, T. (2014) Homosociality: In Between Power and Intimacy. SAGE Open, 4(1): 1-11.

[14]. Burawoy, M. (2019) Symbolic Violence: Conversations with Bourdieu. Duke University Press, Durham.

[15]. Tjønndal, Anne. (2016) NHL Heavyweights: Narratives of Violence and Masculinity in Ice Hockey. Physical Culture and Sport: Studies and Research, 70(1): 55–68.

[16]. Dhont L. (n.d.) Interview with Lukas Dhont. https://www.Closethefilm.be/en#article-lukas.

[17]. Pascoe, C. J. (2005) ‘Dude, You're a Fag': Adolescent Masculinity and the Fag Discourse. Sexualities, 8(3): 329-346.

[18]. Messerschmidt, J. W. (2016) Masculinities in the Making: From the Local to the Global. Rowman & Littlefield, Lanham, MD.

[19]. Pascoe, C.J. (2022). Bullying as a Social Problem: Interactional Homophobia and Institutional Heteronormativity in Schools. In: Christopher D. (Ed.), The Sociology of Bullying: Power, Status, and Aggression Among Adolescents. New York University Press, New York. pp. 76–94.

[20]. Bird, S. R. (1996) Welcome to the Men's Club: Homosociality and the Maintenance of Hegemonic Masculinity. Gender and Society, 10(2): 120–132.

[21]. Hammaren, N. (2008) Fororten i huvudet: Unga man om kon och sexualitet i det nya Sverige. Atlas, Stockholm.

[22]. Cancian, F. M. (1987) Love in America: Gender and Self-development. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

[23]. Strikwerda, R. A., May, L. (1992). Male Friendship and Intimacy. Hypatia, 7(3): 110–125.

[24]. Connell, R. W., Messerschmidt, J. W. (2005) Hegemonic Masculinity: Rethinking the Concept. Gender & Society, 19(6): 829–859.

Cite this article

Liang,Y. (2024). Masculinity and Homosociality in Western Cinema: Taking Close (2022) as a Case Study. Lecture Notes in Education Psychology and Public Media,60,158-171.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Social Psychology and Humanity Studies

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Nelmes, J. (2012) Gender and Film. Jill, N. (Ed.), Introduction to Film Studies. Routledge, New York. pp.262–297.

[2]. Tasker, Y.(2017) Contested Masculinities: the Action Film, the War Film, and the Western. In: Kristin, L. H., Dijana J., E. Ann K., and Patrice P. (Eds.), The Routledge Companion to Cinema and Gender. Routledge, New York. pp.111–120.

[3]. Purse, L. (2011) Contemporary Action Cinema. Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh.

[4]. Dhont L. (2022) Close. Diaphana Films, France.

[5]. Reeser, T. W. (2015) Concepts of Masculinity and Masculinity Studies. In: Stefan, H. (Ed.), Configuring Masculinity in Theory and Literary Practice. Brill, Leiden. pp. 11–38.

[6]. Brod, H. (1987) The Making of Masculinities: The New Men's Studies. Allen & Unwin, Boston.

[7]. Kimmel, M. (1996) Manhood in America: A Cultural History. Free Press, New York.

[8]. Connell, R. W. (1995) Masculinities. University of California Press, Berkeley.

[9]. Yang, Y. (2020) What's Hegemonic about Hegemonic Masculinity? Legitimation and Beyond. Sociological Theory, 38(4): 318–333.

[10]. Sedgwick, E. K. (1985) Between Men: English Literature and Male Homosocial Desire. Columbia University Press, New York.

[11]. Bird, S.R. (1996) Welcome to the Men's Club: Homosociality and the Maintenance of Bonding, and Male Friendship. Men and Masculinities, 15(3): 249–270.

[12]. Haywood, C., Johansson, T., Hammaren, N., Ottemo, A., Herz, M. (2018). The Conundrum of Masculinities: Hegemony, Homosociality, Homophobia and Heteronormativity. Routledge, New York.

[13]. Hammaren, N., Johansson, T. (2014) Homosociality: In Between Power and Intimacy. SAGE Open, 4(1): 1-11.

[14]. Burawoy, M. (2019) Symbolic Violence: Conversations with Bourdieu. Duke University Press, Durham.

[15]. Tjønndal, Anne. (2016) NHL Heavyweights: Narratives of Violence and Masculinity in Ice Hockey. Physical Culture and Sport: Studies and Research, 70(1): 55–68.

[16]. Dhont L. (n.d.) Interview with Lukas Dhont. https://www.Closethefilm.be/en#article-lukas.

[17]. Pascoe, C. J. (2005) ‘Dude, You're a Fag': Adolescent Masculinity and the Fag Discourse. Sexualities, 8(3): 329-346.

[18]. Messerschmidt, J. W. (2016) Masculinities in the Making: From the Local to the Global. Rowman & Littlefield, Lanham, MD.

[19]. Pascoe, C.J. (2022). Bullying as a Social Problem: Interactional Homophobia and Institutional Heteronormativity in Schools. In: Christopher D. (Ed.), The Sociology of Bullying: Power, Status, and Aggression Among Adolescents. New York University Press, New York. pp. 76–94.

[20]. Bird, S. R. (1996) Welcome to the Men's Club: Homosociality and the Maintenance of Hegemonic Masculinity. Gender and Society, 10(2): 120–132.

[21]. Hammaren, N. (2008) Fororten i huvudet: Unga man om kon och sexualitet i det nya Sverige. Atlas, Stockholm.

[22]. Cancian, F. M. (1987) Love in America: Gender and Self-development. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

[23]. Strikwerda, R. A., May, L. (1992). Male Friendship and Intimacy. Hypatia, 7(3): 110–125.

[24]. Connell, R. W., Messerschmidt, J. W. (2005) Hegemonic Masculinity: Rethinking the Concept. Gender & Society, 19(6): 829–859.