1. Introduction

The veto power of the United Nations Security Council (UNSC), also known as the right of veto, is the authority granted to each of the five permanent members (P5) to block any draft resolutions, even if these resolutions have garnered substantial support from the majority of the member states. This power enables any P5 nation to effectively nullify a resolution. The framers of the UN Charter endowed the P5 with this significant authority to ensure that the major powers would continue to lead international relations, with the objective of maintaining global peace and fostering collective development among all nations. In recent years, almost no country has explicitly supported the existing veto power, except for the P5 [1]. Most countries believe that the veto power "has been exercised with a selfish attitude, primarily aimed at protecting the individual national interests of the permanent members and their allies" [2]. Moreover, several countries have pointed out that the P5's use of the veto essentially constitutes an abuse of power, leading to a growing distrust in the decisions made by major powers. This "crisis of confidence" often leads to doubts about the legitimacy and reasonableness of the resolutions passed by the UNSC; perceived abuse of the veto has become a significant factor impairing the effective functioning of the UNSC. For example, a series of resolutions calling for an immediate and sustained ceasefire in Gaza were vetoed by the US, Russia, and China. During the meeting to vote on draft resolution S/2024/239 on March 22, 2024, several member states observed that the ongoing conflicts of interest among the P5 have exacerbated the Gaza-Israel conflict, which has remained unresolved since October 2023 [3]. Consequently, finding a reasonable method to alter the current exercise of the veto has also emerged as a key focus for UNSC reform.

2. Argument

The author proposes that the regulation of the veto power exercised by the P5 should be implemented through two main steps: (1) Amend and enhance the relevant sections of the UN Charter that pertain to the exercise of veto power; and (2) Revise the procedures for exercising the veto and provide a comprehensive explanation of these procedures, including the introduction of a double veto system for use under specific circumstances. By implementing these steps, the exercise of veto power by the P5 could be better regulated, potentially minimizing abuse and improving the efficiency, fairness, and universality of the decision-making process.

3. Difficulties and Solutions: A Historical review of Literature

The exploration of methods for reforming veto power has garnered significant academic interest. This chapter reviews the challenges associated with reforming the UNSC's veto power, examines previous scholarly efforts, and discusses research on reform methods and their outcomes.

3.1. The Difficulty of Changing the Existing Veto Power

The question of whether the veto power can be abolished is a contentious issue among scholars, many of whom view it as largely immutable. The historical context underscores the significance of the veto: the major powers agreed to join the UN primarily because it afforded them substantial authority, notably the veto power. This unique authority could only be exercised through the framework of the UN, necessitating cooperation among the powers. As one author aptly notes, "But to deploy those powers, they had to cooperate." [4]. Moreover, it has been clearly stated by the great powers that their continued participation in the UN was predicated on the retention of their veto rights over all matters except procedural ones [5]. Historical precedents from both Russia and the US reaffirm that any attempts to modify their veto powers would likely be vetoed [1]. An analysis of the UN Charter, specifically Articles 24, 30, and 34, in conjunction with a comparative examination of ongoing conflicts in the Middle East, leads to the conclusion that legal provisions alone are insufficient for the effective implementation of decisions. Furthermore, consensus among member states does not necessarily result in action [6]. Disagreements among the P5, often driven by conflicting national interests, frequently result in inefficiencies within the UNSC’s problem-solving capabilities. Further compounding these challenges, another scholar contrasts the principles outlined in the UN Charter with the practices observed in recent UNSC resolutions and reports. It is widely believed among member states that the P5 have misused their veto power in ways that are undemocratic. Specifically, adherence to the stipulations of Article 27(3) of the UN Charter by the permanent members has been selective, aligning only when convenient or advantageous [7]. Additionally, the deployment of what is termed the "pocket veto" by the P5 leads to a lack of transparency in the resolution process, as some draft resolutions are prevented from even being formally considered, suggesting inappropriate or potentially illicit applications of the veto power.

3.2. Existing Solutions

From a political perspective, some ethicists advocate for reforms to the veto power in the vein of "democratic reform." These proponents assert that the P5 members bear a moral obligation to uphold international peace and security, and that their conduct should be guided by ethical principles [8]. They urge the P5 to act with prudence in matters that might involve war, genocide, and crimes against humanity, and call for these major powers to assume greater responsibilities. However, altering the fundamental structure of the UN presents substantial challenges [9]. The amendment process of the UN Charter demands unanimous approval from the members of the UNSC, specifically without any P5 member exercising their veto. Historically, the veto power was pivotal to the establishment of the UN, with the P5 typically wielding this power to either maximize their national interests or ensure their own protection, rendering any attempt to eliminate the veto power as seemingly impractical.

In addition to the methods previously mentioned, many also support modifications to the veto and related rules. The author advocates for a more specific veto model, termed "vetoing the veto," [10]. which is based on Major Keith L. Sellen's proposal for "Double majority votes." The author draws a comparison between the UN system and the US Congress, using the "checks and balances" system of the U.S. government to explain how veto power operates according to this theory. However, the author also acknowledges the extremely low likelihood that the P5 will voluntarily relinquish their veto power in the pursuit of abstract notions of national equality and legitimacy. Nonetheless, Sellen's proposal could guide other reforms. Other scholars have summarized proposals from various countries, including the African Union and some member states, suggesting that veto power should be limited by requiring a greater number of vetoes (≥2) [1]. Furthermore, the author notes proposals from other nations where veto power would be excluded in certain specific resolution areas, or decisions to exercise the veto could be overturned by a two-thirds majority. More practical methods have been proposed, most of which shy away from a "radical change" to the UN Charter. Regarding the extension of veto power to potential non-permanent members, the G4 and the Coffee Club have expressed opposing views. The G4 argues that such an extension represents the equal rights of more countries, whereas the Coffee Club contends that this expansion would more likely compromise the efficiency or legitimacy of resolutions by member states, potentially increasing the risk of paralysis within the UNSC.

4. Data and Case Studies on the Exercise of Veto Power

4.1. Characteristics of Veto Power Exercise

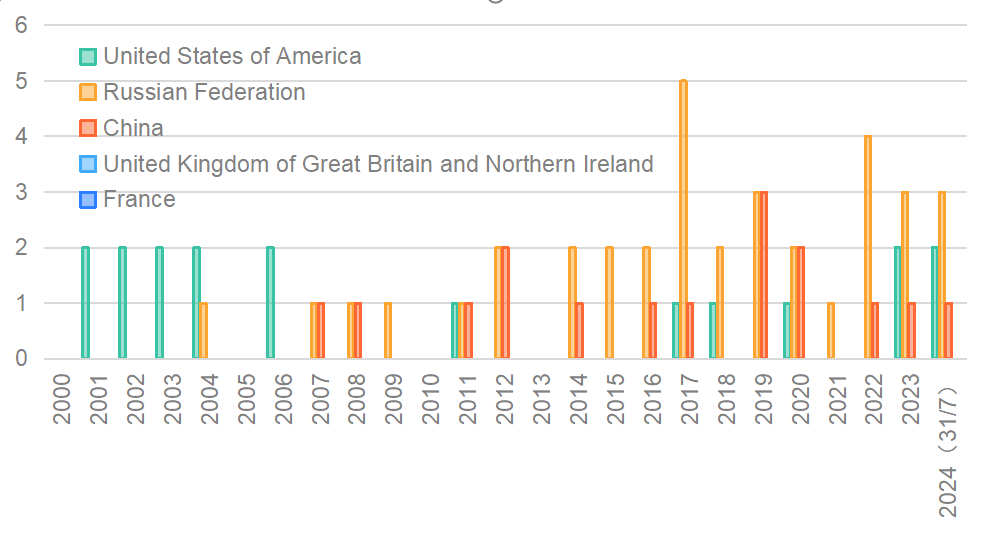

Before proposing changes to the exercise of veto power by the P5, it is essential to comprehend the characteristics of their use of this power. This paper analyzes the frequency, content, and rationale behind the P5's exercise of veto power from 2000 to 2024 (as of July 31), utilizing data from the UN website. Employing statistical and analytical methods, data enumeration, and graphical representation, this analysis is further enriched with specific case studies. The feasibility of current approaches to reforming the veto power is evaluated comprehensively, with the aim of identifying potential new methodologies. It is important to note that between 2000 and 2024, the UNSC proposed a total of 1,468 draft resolutions, of which 1,388 were passed (including those not requiring a formal resolution). Apart from the 26 draft resolutions that did not pass due to failing to secure the required nine affirmative votes, the remaining 54 failed due to the exercise of veto power by the P5, equating to a probability of a draft resolution being vetoed by the P5 at only 3.68%. Statistically, this demonstrates that the exercise of the veto by the P5 is "relatively infrequent." Consequently, within this paper, the term "frequent" in the context of veto power exercise is used solely for comparative analysis across different time periods and among different countries.

4.2. Characteristics of Veto Power Frequency

Regarding frequency, as illustrated in Figure 1, Russia has exercised the veto most frequently over the past 24 years, totaling 36 instances. This is followed by the United States with 18 instances and China with 16. A notable shift occurred around 2006 and 2007; the United States exercised its veto power more frequently before 2006 but less so after 2007, experiencing a resurgence only in 2023. Conversely, Russia used its veto only once in the initial six years, but from 2007 onwards, it has exercised its veto more frequently than any other P5 member, amounting to 35 instances. Since 2007, China’s use of the veto has also been notably active. Intriguingly, all of China's vetoes during this period were in conjunction with Russia, indicating that China has not independently vetoed any resolution. This observation also implies that joint exercises of veto power by two P5 members on the same resolution have been rare over the past 24 years. Neither the United Kingdom nor France has exercised their veto power during this period.

Figure 1: Use of the veto by the five permanent members (2000-31/7/2024).

4.2.1. Characteristics of Veto Content

In terms of content, as depicted in Figure 2, issues concerning the Middle East and Palestine have been primary points of contention among the US, Russia, and China over the past 24 years. Of the draft resolutions vetoed, 36 addressed these topics, constituting two-thirds of all vetoed drafts. During this period, the US exercised its veto 15 times, with 9 occurrences before 2006. Russia employed its veto 21 times, all post-2011. Similarly, China's 12 vetoes were also post-2011 and consistently in conjunction with Russia. Notably, all 15 Middle East-related draft resolutions vetoed by the US during this timeframe were supported by both China and Russia. Conversely, the 21 resolutions either vetoed or abstained by China and Russia were endorsed by the US. It is evident that China and Russia frequently align their positions when exercising veto power concerning these issues. However, the US and Russia often display divergent attitudes towards issues in the Middle East, reflecting a nuanced adversarial relationship. Despite the UK and France advocating for a "less frequent exercise of the veto," their impact have not been particularly significant. Their abstention votes, however, suggest a "latent stance" that tends to align more closely with the US.

Figure 2: Main content of the exercise of veto by P5.

4.3. Reason for veto on the Middle East Issue

From the data presented, consider the draft resolution S/2024/239 proposed on March 22, 2024, which addressed issues in the Middle East and Palestine. The US emphasized the need for an immediate ceasefire in Gaza and humanitarian relief for all parties. However, Russia and China vetoed this resolution, arguing that the US had deliberately used ambiguous language in the proposal and failed to address Israeli actions. Earlier, on February 20 of the same year, the US vetoed draft resolution S/2024/173, which also called for a ceasefire in Gaza. This veto marked the second time since December 2023 that the US had exercised its veto power, citing the facilitation of hostage agreement negotiations between Israel and Hamas as the reason. Additionally, a subsequent draft resolution proposed on April 18 of the same year, aimed at admitting Palestine as a new UN member, was also vetoed by the US. It is evident that the US frequently uses its veto power on issues related to the Middle East to shield Israel from the impact of UNSC resolutions. The conflicts among countries, especially the major powers within the P5, have intensified through mutual blame, often making it difficult to reach a consensus on issues concerning their interests. This may explain why the Gaza-Israel conflict remains unresolved.

Regarding draft resolutions on issues related to the Middle East, Palestine, and Syria, China and Russia have jointly exercised their veto power on twelve occasions. Among these, two resolutions were proposed by the US, five by European countries (notably Belgium, Germany, and France), and the remaining five jointly by the US and European nations. Both China and Russia have justified their exercise of the veto by stating that the proposals contained initiatives and language that interfered with the sovereignty and internal affairs of other countries. Moreover, despite the resolutions advocating for ceasefires and the prevention of conflict escalation, they have, in fact, contributed to the politicization of humanitarian aid [11]. Notably, Russia has unilaterally exercised its veto power nine times in response to draft resolutions concerning these areas and beyond, often expressing strong condemnation and opposition to proposals from the US, the UK, and France. While China has not shown the same level of opposition as Russia, it has chosen to abstain in the nine instances where Russia has unilaterally exercised its veto. The manner and frequency with which China and Russia exercise their veto power, as well as their stated reasons, indicate a degree of coordination between the two countries in specific areas.

5. Suggestions for Veto Power Reform

5.1. Legal Foundation

To effectively regulate the exercise of veto power by the P5 and to enhance the UN's capacity and efficiency in resolving global issues, it is essential to amend or provide a detailed interpretation of the sections of the UN Charter concerning veto power. The most crucial factor influencing the feasibility of this approach is how to reasonably and legally persuade the P5 to approve modifications to the procedures for exercising veto power while ensuring their core interests are protected. For instance, Article 27 of the UN Charter describes the voting rights enjoyed by the members of the Security Council. Although the article does not explicitly stipulate the veto power, it acknowledges the right to a single veto based on "Great Power unanimity". The author intends to refine the procedures for the exercise of veto power, focusing on their specific practical applications and the proposed "double veto" system, which is distinct from the double veto mentioned earlier.

5.2. "Double Veto System"

The double veto system requires that if a draft resolution is widely agreed upon, it must be vetoed by at least two or more UNSC permanent members to prevent its adoption. "Common approval" refers to a scenario in which a majority of both permanent and non-permanent members have indicated their approval. This implies that the resolution has already received 12 affirmative votes (over 80% of the total votes, corresponding to a 4:5 approval ratio) or more before it is vetoed. To illustrate, with the minimum requirement of 12 votes, the main scenarios could be 10 votes from non-permanent members and 2 from permanent members or 9 votes from non-permanent members and 3 from permanent members. Unlike the standard requirement of 9 votes for passage, the 12-vote requirement not only raises the threshold for the operation of the double veto system but also provides specific criteria for the condition of "common approval." It distinguishes the normal exercise of single veto power by the P5, focusing on their fundamental rights and moderately regulating the exercise of power. At the same time, it safeguards the rights of non-permanent by allowing them room for choice.

From the analysis, the P5 has rarely jointly exercised their veto power on the same resolution. More commonly, a draft resolution meeting the criteria for common approval tends to be vetoed by a single P5 country. However, under this system, China and Russia, despite having different state systems, political systems, and ideologies, jointly exercise their veto power on the same proposal due to their shared views on certain major international issues and their strategic consensus on the same topic, based on mutual interests and support. Therefore, China and Russia coordinate their positions during decision-making and jointly exercise their power to protect respective interests and common goals.

This system thus grants the P5 "potential power" but also imposes "potential obligations" on them. Under the double veto system, the P5 have the authority to decide the validity of a veto declaration made by one of their members. They can achieve this through their veto power to ensure a "checks and balances" mechanism (this aligns with Sellen's proposal). However, the prerequisite is that before the P5 exercise their veto power to protect their own interests, they must consider the interests of other countries and the potential consequences. Consequently, they are compelled to optimize their own interests while encouraging all member states, particularly the permanent members, to pursue shared interests and consensus. This approach aims to minimize disputes among member states over divergent interests, which could otherwise lead to the failure to pass substantive resolutions. If the exercise of veto power in specific circumstances is not governed by rights and obligations, major powers might concentrate solely on maximizing their own interests without any effort to seek broader cooperative consensus, a situation that risks leading to the abuse of veto power.

Furthermore, the exercise of the veto by major powers is also, to some extent, linked to changes in their international status and power dynamics. Comprehensive national strength underpins the exercise of veto power, and the employment of this power, in turn, influences the authority and image of the major power in international relations. This "consensus" suggests that the use of the veto power should be the result of careful deliberation rather than impulsive action; it should not be employed capriciously in situations that do not necessitate such measures. Therefore, the double veto system offers the P5 an opportunity to consider the prudent exercise of their veto power. Simultaneously, for other countries under this system, particularly emerging ones like the G4 and the Coffee Club, major powers may need to take their interests into account or seek their support on various issues. This system represents a second-best option, given the current challenges in enhancing the international status and influence of countries outside the P5.

6. Conclusion

This system reform, however, is not without limitations. The most significant of these is the potential for coalition-building driven by overlapping interests. The analysis of veto usage above reveals alliances and oppositions among the P5. However, the proposed system necessitates mutual understanding and support among major powers. They should return to the original intent of the veto power, which emphasizes consensus over confrontation. Under the proposed system, if a country seeks to protect its interests against a resolution likely to receive common approval, it must also secure the support of another major power to exercise their veto. While there is a possibility that nations might form "interest groups," the aim of revising the veto procedure is not to limit the P5's use of their veto indiscriminately nor to advocate for its gradual elimination. Instead, the objective is to regulate the P5’s use of veto power through procedural reforms, prompting them to undertake comprehensive considerations before making decisions. It is essential to adopt a moderate approach that avoids radical changes to the UN Charter or the existing veto rights of the P5. Such reforms are more likely to be acceptable and practically implementable.

References

[1]. Jan, Tom. 2005. "Veto Reform Proposals."Egmont Institute. SECURITY COUNCIL REFORM: A NEW VETO FOR A NEW CENTURY?:19-24. http://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep06699.6.

[2]. Al Shraideh, S. 2017. "The Security Council's Veto in the Balance. "JL Pol'y & Globalization, 58, 135.

[3]. UN Security Council Meetings & Outcomes Tables. 2024. S/PV.9584. 9584th meeting. https://undocs.org/en/S/PV.9584Alan.1969.

[4]. Jerónimo, Kal, Viva. 2023. "Why The UN Still Matters: Great-Power Competition Makes It More Relevant—Not Less." Foreign Affairs. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/united-states/why-united-nations-still-matters.

[5]. Security Council Report. 2015. "The Veto". https://securitycouncilreport.org.

[6]. Olayiwola, Sanni. 2024. "Interrogating the Role of the United Nations Security Council and the Use of Veto Power in the Israeli-Palestinian Crisis."Journal of Research in Education and Society 15(1): 39-52.

[7]. Granja, Aracelly. 2017. "UNSC Reform in a Post-Cold War Era: Eliminating the Power of Veto." Master's thesis. University of Ottawa. https://doi.org/10.20381/ruor-20288

[8]. Dickson, E. Ekpe, T. Abumbe. 2024. "Russia Invasion of Ukraine, Veto Power and the Position of the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) in Conflict Prevention and Maintenance of International Peace and Security." Journal of Public Administration, Policy and Governance Research 2(1):161-175.

[9]. Acharya, Amitav, Dan. 2020. "The United Nations." Global Governance 26(2) : 221–35. https://doi.org/10.1163/19426720-02602001.

[10]. Lulseged, Lamrot. 2013. "Vetoing the veto: voting reform and the United Nations security council." Master's thesis. St. Thomas University. https://summit.sfu.ca/item/13582

[11]. UN Security Council Meetings & Outcomes Tables. 2024. SC/15637. https://press.un.org/en/2024/sc15637.doc.htm

Cite this article

Zhou,Y. (2024). Double Veto System: Reforming the Veto and Voting Rules in UN Security Council. Lecture Notes in Education Psychology and Public Media,65,150-156.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on International Law and Legal Policy

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Jan, Tom. 2005. "Veto Reform Proposals."Egmont Institute. SECURITY COUNCIL REFORM: A NEW VETO FOR A NEW CENTURY?:19-24. http://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep06699.6.

[2]. Al Shraideh, S. 2017. "The Security Council's Veto in the Balance. "JL Pol'y & Globalization, 58, 135.

[3]. UN Security Council Meetings & Outcomes Tables. 2024. S/PV.9584. 9584th meeting. https://undocs.org/en/S/PV.9584Alan.1969.

[4]. Jerónimo, Kal, Viva. 2023. "Why The UN Still Matters: Great-Power Competition Makes It More Relevant—Not Less." Foreign Affairs. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/united-states/why-united-nations-still-matters.

[5]. Security Council Report. 2015. "The Veto". https://securitycouncilreport.org.

[6]. Olayiwola, Sanni. 2024. "Interrogating the Role of the United Nations Security Council and the Use of Veto Power in the Israeli-Palestinian Crisis."Journal of Research in Education and Society 15(1): 39-52.

[7]. Granja, Aracelly. 2017. "UNSC Reform in a Post-Cold War Era: Eliminating the Power of Veto." Master's thesis. University of Ottawa. https://doi.org/10.20381/ruor-20288

[8]. Dickson, E. Ekpe, T. Abumbe. 2024. "Russia Invasion of Ukraine, Veto Power and the Position of the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) in Conflict Prevention and Maintenance of International Peace and Security." Journal of Public Administration, Policy and Governance Research 2(1):161-175.

[9]. Acharya, Amitav, Dan. 2020. "The United Nations." Global Governance 26(2) : 221–35. https://doi.org/10.1163/19426720-02602001.

[10]. Lulseged, Lamrot. 2013. "Vetoing the veto: voting reform and the United Nations security council." Master's thesis. St. Thomas University. https://summit.sfu.ca/item/13582

[11]. UN Security Council Meetings & Outcomes Tables. 2024. SC/15637. https://press.un.org/en/2024/sc15637.doc.htm