1.Introduction

The Terms of Reference system is a procedural mechanism widely used in international commercial arbitration. Simply put, the Terms of Reference, required by the arbitration rules of international commercial arbitration institutions, is a procedural document jointly drafted by the arbitration institution and the parties. This document, prepared after the constitution of the arbitral tribunal and before the commencement of formal hearings, confirms basic information about the parties, their claims, the seat of arbitration, and the substantive rules applicable to the arbitration [1]. Initially, the system was designed to enhance the recognition and enforceability of arbitration agreements. However, with the development of international commercial arbitration and the increase in the number of signatories to the New York Convention, the original purpose of the Terms of Reference system has gradually diminished. Today, the system aims to establish a framework in advance, defining the subject matter of the dispute and procedural issues to facilitate a more efficient arbitration process [2]. The system was first created by the International Court of Arbitration of the International Chamber of Commerce (ICC) and has since been adopted or adapted by many other international commercial arbitration institutions [3]. In particular, it plays a critical role in resolving whether new claims can be incorporated into ongoing arbitration proceedings, contributing positively to both theoretical and practical advancements in international commercial arbitration.

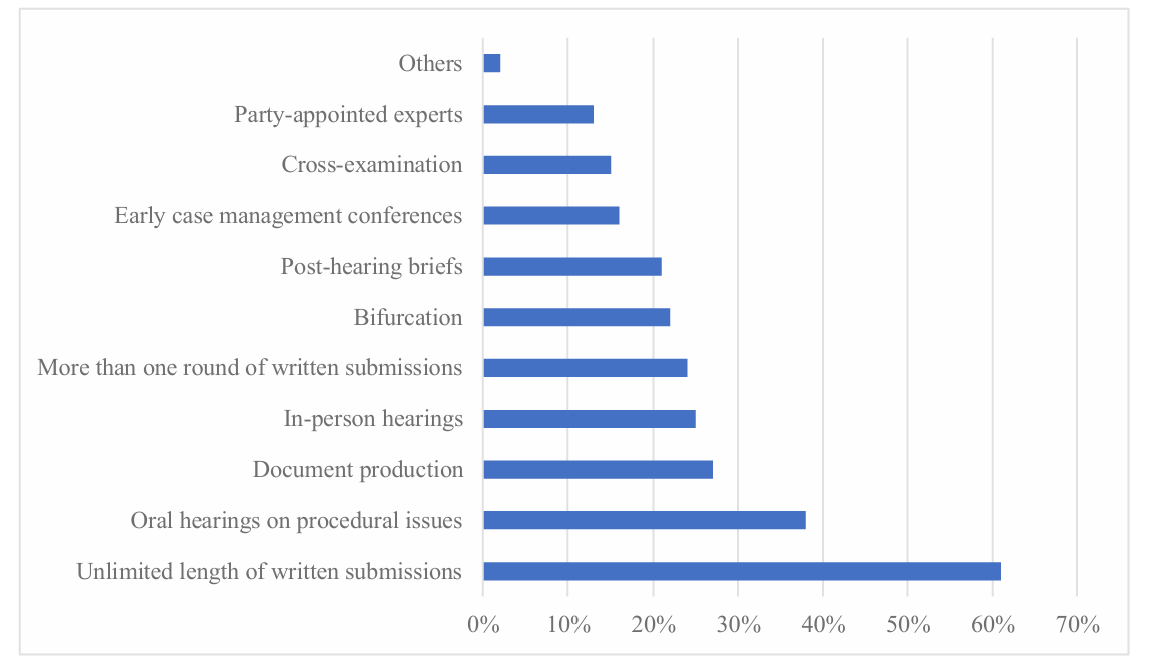

Efficiency is one of the core objectives of international arbitration, and the original intention of the Terms of Reference system is to promote efficiency by optimizing procedures and fostering active cooperation among participants [4]. According to recent studies, 61% of respondents identified the complexity and length of document drafting as a major obstacle to arbitration efficiency, while 38% highlighted procedural discussions during oral hearings as inefficient [5]. However, the Terms of Reference system reflects a contradiction regarding these factors. On the one hand, the value of the Terms of Reference system has been questioned. Critics argue that it is an unnecessary, overly detailed formalistic mechanism. Its mandatory application undermines party autonomy and arbitration flexibility, adding procedural steps to document drafting. Particularly after losing its original purpose of enhancing the recognition and enforceability of arbitration, it has become an outdated system [6]. On the other hand, proponents maintain that pre-hearing procedures in international arbitration, such as the Terms of Reference, have intrinsic value [7]. Once the Terms of Reference is finalized, it can significantly enhance the efficiency of the overall arbitration process, saving time that would otherwise be spent on procedural discussions during oral hearings.

Figure 1: If you were a party or counsel, which of the following procedural options would you be willing to do without if this would make your arbitration cheaper or faster?

The first part of this article serves as an introduction, establishing efficiency as a key value pursued in international commercial arbitration. It highlights the inherent contradiction between the Terms of Reference system's original intention to enhance efficiency and the inefficiency problems exposed during its implementation. Addressing these inefficiencies offers significant guidance for major arbitration institutions and the development of arbitration in China. The second part of the article examines the relationship between the Terms of Reference system and arbitration efficiency from the perspective of law and economics, using Article 23 of the ICC Arbitration Rules as a case study. It specifically identifies design and operational issues in Article 23(4), which governs whether new claims can be incorporated into ongoing arbitration proceedings based on the Terms of Reference. These issues undermine the efficient progression of arbitration. The third part responds to the identified problems, proposing solutions from four perspectives to address the inefficiencies in the operation of the Terms of Reference system. The conclusion reviews the discussion, reflects on the limitations of this article, and offers prospects for unresolved issues that require further exploration.

2.Efficiency Insights: The Value of the Terms of Reference System in Improving International Commercial Arbitration Rules

When resolving international commercial disputes, parties can choose between international commercial arbitration or cross-border litigation [8]. Since commercial dispute entities aim to maximize economic benefits, international commercial arbitration is often preferred due to its efficiency advantages [9]. First, the New York Convention is widely adopted by countries, providing convenience in recognizing and enforcing arbitral awards, making arbitration a preferred dispute resolution method for cross-border commercial contracts. By contrast, no multilateral agreements exist that require civil courts in different countries to immediately enforce each other's judgments based on such agreements [10]. Second, a critical difference between litigation and arbitration lies in procedural rigidity [11]. International commercial arbitration rules are chosen by mutual agreement of the parties, offering greater flexibility and freedom, which significantly enhances the efficiency of dispute resolution. Finally, international commercial arbitration adopts a finality principle, meaning that disputes are resolved conclusively through a single arbitration proceeding. Compared to the appeals and retrials common in litigation, this ensures disputes are resolved in a more straightforward and stable manner. Thus, efficiency is an essential value pursued by international commercial arbitration.

As a pre-hearing preparatory procedure, the Terms of Reference helps define key elements such as basic party information, arbitration claims, and a list of pending issues in advance. This adds certainty to the arbitration process, preventing omissions of claims or overly broad or unenforceable pending issues. Consequently, the system contributes to improving both the efficiency and effectiveness of arbitration.

The Terms of Reference system was originally introduced by the International Court of Arbitration of the International Chamber of Commerce (ICC) [12]. While it has not yet achieved universal application, it holds significant reference value for other arbitration institutions aiming to enhance their arbitration procedures. On one hand, some arbitration institutions have already adopted this system. For example, Article 28(4) of the Madrid International Arbitration Center Rules in Spain explicitly incorporates the Terms of Reference system and its procedural rules for admitting new claims. Similarly, Article 35 of the Arbitration Rules of the China International Economic and Trade Arbitration Commission (CIETAC) provides that the arbitral tribunal may draft a Terms of Reference document for the case if deemed necessary. On the other hand, even arbitration institutions that have not directly implemented the Terms of Reference system can still draw upon its provisions for procedural issues, such as the criteria for admitting new claims into arbitration proceedings. For instance, Article 20 of the Singapore International Arbitration Centre (SIAC) Rules stipulates that changes to claims must consider whether they fall within the scope of the arbitration agreement. However, arbitration agreements can only predetermine arbitration as the dispute resolution mechanism and cannot anticipate the substantive content of disputes and claims arising later. Consequently, compared to drafting a Terms of Reference after the dispute arises, this provision lacks rationality and reliability. At its core, the drafting of the Terms of Reference is a case management tool akin to a pre-hearing conference. Regardless of the arbitration institution, case management is necessary. While the methods may differ, the objective is the same: to streamline arbitration proceedings and enhance efficiency [13]. Therefore, studying the impact of the Terms of Reference system on arbitration efficiency holds universal significance.

The original design purpose of the Terms of Reference system in international commercial arbitration was to improve efficiency. However, its current application mechanism may instead create inefficiencies and inconvenience for arbitrators and parties. On one hand, one of the most prominent rules in the Terms of Reference system is its role in determining the feasibility of admitting new claims into ongoing arbitration proceedings based on its content and scope. This rule makes the inclusion of new claims after the Terms of Reference is finalized more stringent. Furthermore, the rules for consenting to new claims are ambiguous and largely subject to the arbitrator's discretion, potentially disrupting the smooth progression of arbitration and even causing procedural delays. On the other hand, the Terms of Reference system, as a mandatory pre-hearing preparation mechanism, requires the cooperation of both parties, the review by the arbitral tribunal, and additional documentation management procedures. These steps inevitably increase time costs, opportunity costs, and arbitration expenses [14]. Thus, the Terms of Reference system may face challenges related to both time efficiency and economic efficiency.

Some scholars argue that the Terms of Reference system has lost its research significance, as it no longer enhances enforceability over time and has not been universally adopted by arbitration institutions. This view reflects a misunderstanding of the system [15]. Although the Terms of Reference system has evolved beyond its original purpose, it now provides new procedural value by preventing the surprise introduction of evidence, safeguarding procedural fairness, enhancing arbitration efficiency, and protecting the interests of commercial parties. Certainly, drafting a Terms of Reference increases the time cost of arbitration preparation. However, as the saying goes, "sharpening the axe does not delay the work of cutting wood." Overall, the Terms of Reference provides a procedural framework that improves the stability and predictability of arbitration, ensuring the smooth progression of the proceedings [16] and enhancing efficiency as a whole. Regarding its lack of universal application among arbitration institutions, this should be understood in the context of the specific characteristics of the International Court of Arbitration of the ICC. According to 2020 statistics, a significant proportion of the cases handled by the ICC involved high monetary values, with the largest share being disputes valued between USD 10 million and 30 million [17]. Moreover, the ICC Arbitration Rules stipulate that cases involving claims below USD 3 million can follow expedited procedures without requiring a Terms of Reference. Cases with higher monetary stakes often involve more complex factual disputes and claims, requiring a more careful approach. The Terms of Reference system helps clarify case facts and the actual points of contention between the parties, ensuring that arbitration claims are neither overly broad, which could delay proceedings, nor overly narrow, which might exclude relevant substantive issues from review [18]. Additionally, under the principle of party autonomy in arbitration, parties selecting ICC arbitration are presumed to have understood its typical case types, arbitration rules, and strong administrative characteristics. This selection represents their acceptance of the ICC’s procedural management authority [19]. When parties submit their disputes to the ICC for arbitration, a contractual relationship is effectively formed between the parties and the institution or arbitrators. This contract incorporates the arbitration agreement and the applicable arbitration rules, meaning that these rules are not excluded from the parties’ autonomy [20]. The value of rules is not determined solely by their widespread application but should be evaluated based on the specific needs of commercial parties in different scenarios.

Table 1: 2020 Statistical Data on Case Values at the ICC International Court of Arbitration

|

AMOUNTS IN DISPUTE IN CASES FILED IN 2020 |

% OF TOTAL NUMBER OF CASES |

|

≤50,000 |

1.7% |

|

>50,000 ≤100,000 |

2.3% |

|

>100,000 ≤200,000 |

2.9% |

|

>200,000 ≤500,000 |

5.7% |

|

>500,000 ≤1 million |

8% |

|

>1 million ≤2 million |

10.5% |

|

>2 million ≤5 million |

14.5% |

|

>5 million ≤10 million |

12.1% |

|

>10 million ≤30 million |

15.7% |

|

>30 million ≤50 million |

6.1% |

|

>50 million ≤80 million |

3.8% |

|

>80 million ≤100 million |

2% |

|

>100 million ≤500 millon |

6.6% |

|

>500 million |

1.9% |

|

Not quantified |

6.1% |

From the perspective of efficiency as a core value pursued by international commercial arbitration, the Terms of Reference system holds reference value for arbitration institutions that have adopted or not yet adopted this rule. As a case management tool employed by various arbitration institutions, its ultimate goal is to improve arbitration efficiency. Moreover, the system offers unique advantages, such as enhancing the overall efficiency of handling complex cases and ensuring procedural justice by preventing the surprise introduction of evidence. Finally, under the principle of party autonomy, parties have the freedom to choose arbitration institutions. When parties select the ICC, they implicitly acknowledge and accept its rules and their strong administrative characteristics. Therefore, the focus should not be on abandoning the Terms of Reference system but on improving its functionality and addressing the challenges that arise during its operation and development.

In July 2022, the Central Committee for Comprehensively Advancing Law-Based Governance deployed pilot projects for establishing international commercial arbitration centers in Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, Shenzhen, and Hainan Province. On April 9, 2024, China’s Ministry of Justice held a meeting in Shanghai to review the progress of these pilot projects, share experiences from the pilot regions, and outline plans for the next phase [21]. Against this backdrop, China aims to establish itself as a global hub for international arbitration and should further refine its arbitration institutions' rules. While the Arbitration Rules of the China International Economic and Trade Arbitration Commission (CIETAC) include provisions for the Terms of Reference system, these rules lack integration with other procedural mechanisms, such as coordination with the procedural order system, to accelerate the efficiency of international commercial arbitration proceedings [22]. Thus, this study of the Terms of Reference system also provides valuable insights for improving CIETAC’s arbitration rules.

3.Efficiency Analysis: The Terms of Reference System as Represented by Article 23 of the ICC Arbitration Rules

3.1.Pursuing Maximum Operational Efficiency of Legal Systems: A Necessity in Law and Economics

International commercial entities are inherently profit-driven [23], and the nature of international commercial arbitration requires us to evaluate the actions of parties and arbitrators, as well as the formulation of arbitration rules, from a law and economics perspective. The core idea of economic analysis in law is "efficiency." The principle of efficiency is the most fundamental and primary principle, aiming to allocate and utilize resources in a manner that maximizes value. In recent years, major international arbitration institutions have frequently amended their rules, with the ultimate goal of ensuring that commercial arbitration, as an alternative dispute resolution mechanism, maintains its advantages of speed, efficiency, and cost-effectiveness [24]. Thus, the value pursued by international commercial arbitration aligns seamlessly with the core principles of law and economics.

The Coase Theorem forms the central framework of law and economics theory [25]. Its second law posits that when transaction costs are positive, different definitions and allocations of rights lead to different efficiencies in resource allocation. According to the Coase Theorem, the best laws are those that minimize transaction costs [26]. However, international commercial arbitration currently faces two major efficiency challenges. First, arbitration costs and the time required to resolve cases are both increasing, raising doubts about the long-held perception of commercial arbitration as low-cost and fast-paced [27]. Second, the issues of frivolous claims and procedural abuse have also significantly contributed to the decline in arbitration efficiency [28]. The Terms of Reference system was initially designed to address these two efficiency issues. Disputes resolved through international commercial arbitration span various fields, including contract disputes and other property rights disputes. This paper focuses on the Terms of Reference system's design flaws within the context of typical sales contract disputes. Since the Terms of Reference system was created and has been long promoted as a representative procedural mechanism by the International Court of Arbitration of the ICC, this section will analyze the system using the relevant provisions in the ICC 2021 Arbitration Rules.

3.2.The First Three Provisions of Article 23 of the ICC Arbitration Rules Enhance the Efficiency of Drafting the Terms of Reference

Article 23 of the ICC Arbitration Rules (2021) comprehensively addresses the Terms of Reference system. The first paragraph specifies the contents of the Terms of Reference, the second sets the timeline for its drafting, the third outlines procedures when a party refuses to participate, and the fourth imposes restrictions on parties introducing new claims.

The first paragraph of Article 23 requires the Terms of Reference to include essential information such as the names, addresses, and contact details of the parties and arbitrators, the seat of arbitration, correspondence addresses, summaries of the parties’ respective claims and relief sought, a list of issues to be determined, and a detailed description of the applicable procedural rules. This paragraph ensures that all basic information required during arbitration is clearly outlined and provides a preliminary prima facie assessment of whether the disputes submitted to arbitration have a reasonable factual basis [29]. Additionally, this provision allows for some flexibility for both the parties and the arbitral tribunal. On the one hand, it explicitly states that the list of issues to be determined may be outlined "when the arbitral tribunal considers it necessary," granting the tribunal discretionary authority. On the other hand, the provision includes inherently vague terms like "most recent submissions," which allow the parties and tribunal to tailor the specificity of the Terms of Reference to the needs of individual cases. This flexibility enhances the efficiency of drafting the Terms of Reference.

The second paragraph of Article 23 stipulates that the general timeline for drafting the Terms of Reference is 30 days, while also allowing for extensions under exceptional circumstances with the consent of the arbitral institution. In the exploration of commercial arbitration mechanisms, balancing the acceleration of arbitration procedures with the avoidance of procedural redundancy remains a common challenge. Therefore, setting a clear timeline prevents parties from using the Terms of Reference system as a means to delay arbitration proceedings, making such a limitation necessary [29].

The third paragraph of Article 23 of the ICC Arbitration Rules (2021) addresses how to proceed when a party refuses to cooperate in drafting the Terms of Reference. While arbitration emphasizes party autonomy, it differs from party-driven mediation models [30]. Although the Terms of Reference influences the progression of the arbitration process and certain specific procedural issues that concern the parties’ interests, if a party refuses to participate in its drafting, the Terms of Reference remains a mandatory requirement (except in expedited procedures). To prevent potential malicious delays by the parties, this provision grants the arbitral tribunal the authority to approve the Terms of Reference and proceed with arbitration even in the absence of a party’s participation. This provision reflects a balance between the values of efficiency and fairness. Fairness and efficiency serve as essential guiding principles in the operation of the legal system, directing the rational allocation of legal and social resources. However, these values often exist in a state of profound tension—both mutually adaptable and inherently contradictory [31]. In the realm of international commercial arbitration, arbitration institutions tend to prioritize efficiency when drafting rules.

3.3.Inefficiency in the Design of Article 23(4) of the ICC Arbitration Rules

The first three paragraphs of Article 23 of the ICC Arbitration Rules (2021) outline the rules followed before the completion of the Terms of Reference, employing sufficient flexibility to enhance the drafting efficiency during the preparatory phase. However, once the process transitions from the preparatory phase to the hearing phase, this flexibility, when viewed from another perspective, can introduce ambiguity and confusion, potentially reducing efficiency [32]. This issue is exemplified by the rules on introducing new claims under the first four paragraphs of Article 23.

According to these provisions, after the Terms of Reference is signed or approved by the arbitral tribunal, no party may submit a new claim that falls outside the scope of the Terms of Reference, unless the tribunal permits it after considering the nature of the new claim, the stage of the arbitration proceedings, and other relevant circumstances. The author identifies four issues with this provision.

The first issue is the lack of a clear definition of "new claims" [33]. The ICC Arbitration Rules (2021) only provide a basic explanation in Article 2(5), stating that "claims include any claim by one party against any other party," without specifically defining new claims. The new content submitted by a party may be merely a supplement to the arguments of an original claim or an entirely independent new claim. This lack of clarity makes it difficult to determine the relationship between multiple claims submitted by a party. Consequently, it is challenging to ascertain whether the prerequisites for applying this provision have been met, as the nature of a submitted claim is not easily identified as a "new claim" under the rule.

The second issue concerns the lack of clear criteria for determining whether a new claim falls outside the scope of the Terms of Reference. While this provision generally prohibits parties from submitting new claims that fall outside the Terms of Reference, it implicitly allows parties to submit new claims that fall within its scope. However, neither this provision nor other clauses in the ICC Arbitration Rules (2021) define the "scope of the Terms of Reference," making it difficult to assess whether a new claim falls within this scope. Based on a restrictive and logical interpretation of the text, the "scope of the Terms of Reference" in this provision should refer to the scope of the claims by each party as outlined in the completed Terms of Reference. However, in some ICC arbitral awards, other content in the Terms of Reference, such as the summary of relief sought and the list of issues to be determined, has also been used as reference points for determining whether a new claim falls within the scope [34]. A more significant issue arises from the fact that the list of issues to be determined lacks legal binding force. Unlike the addition of new claims, adjustments or changes to the list of issues are not subject to strict standards, as some issues may be resolved and new ones may emerge during the progression of arbitration [35]. Using the list of issues as a reference point effectively broadens the scope of the Terms of Reference. As a result, there is inconsistency in the application of standards by arbitrators—sometimes strict and other times lenient. This inconsistency affects not only the efficiency of arbitrators in adjudicating but also the efficiency of parties in presenting evidence.

This provision allows for exceptions where parties may submit new claims falling outside the scope of the Terms of Reference, provided three criteria are considered: the nature of the claim, the current stage of the arbitration proceedings, and other relevant circumstances. The third issue lies in the fact that, although these three criteria are provided, they are abstract and lack granularity. As a result, the criteria often become the focus of disputes during hearings, requiring arbitrators to expend significant time and effort in making decisions. This challenge is particularly evident in cases involving multiple contractual disputes between the same parties, disputes under the same contract involving third-party participants, or cases involving multiple contracts and third-party participants. The lack of specificity in these criteria makes the provision difficult for arbitrators to apply in complex factual scenarios, significantly reducing arbitration efficiency.

Consider a case involving multiple contractual disputes between the same parties. Regarding the nature of the claim, the claimant argued that the two claims involved the same disputing parties and arose under a single framework agreement containing a unified arbitration clause. Both claims stemmed from the respondent’s failure to fulfill payment obligations under contracts governed by this framework agreement. However, the respondent objected, asserting that while the claims were under the same framework agreement, they pertained to separate purchase orders within the framework. Each purchase order contained its own independent arbitration clause. Additionally, while the claims were based on the respondent's non-performance of payment obligations, the specific factual grounds for the respondent's defenses differed for each claim. Regarding the stage of the arbitration, the claimant argued that the new claim was introduced midway through the proceedings due to reasons that were objectively unforeseeable and that the claimant promptly submitted the claim upon discovery. The claimant further asserted that the arbitral tribunal had the authority to extend the arbitration process, ensuring the respondent had sufficient time to prepare for the new claim. Conversely, the respondent countered that the claimant’s failure to identify the claim earlier was due to subjective mismanagement rather than objective circumstances. The respondent also suggested that the claimant’s actions raised suspicions of procedural ambush, as the addition of the new claim would cause unreasonable delays and increase the interest payable by the respondent. This example illustrates how claimants and respondents interpret the nature and timing of the claim based on the specific granularity of the case facts. The vagueness of the criteria increases the evidentiary burden on both parties while making it challenging for arbitrators to decide based on the standards. Consequently, arbitration efficiency is diminished.

Finally, through an analysis based on teleological interpretation, it can be observed that while Article 23(4) of the ICC Arbitration Rules (2021) distinguishes between two logical layers—whether a new claim falls within or outside the scope of the Terms of Reference—the paths to achieve these layers and their ultimate objectives overlap. In ICC Case No. 6197 and Case No. 3267, the arbitral tribunal held that "the claim falls within the scope of the Terms of Reference because there is sufficient connection between the new claim and the original claim." Furthermore, in the reasoning provided in the judgments, the tribunal similarly considered the degree of connection between the nature of the new claim and the original claim. This overlaps with the "nature of the claim" criterion used when evaluating new claims that fall outside the Terms of Reference [36]. In other words, the most critical judgment criterion is whether there is a sufficiently close relationship between the new claim and the original claim. If such a relationship exists, the new claim naturally shares the same nature as the original claim, and its introduction is deemed timely and appropriate. Thus, the considerations for whether a new claim falls within or outside the scope of the Terms of Reference—such as its nature and timing—ultimately rely on the same judgment standard. As a result, the supposed distinction between claims falling within or outside the Terms of Reference, and the subsequent evaluation of their nature and timing, lacks substantive logical progression in application. Regardless of whether a new claim falls within or outside the Terms of Reference, the facts and criteria used to determine whether it can be included in the arbitration process are identical. Therefore, the deliberate use of the Terms of Reference as a dividing line in this provision serves no practical purpose.

4.Efficiency Improvement: Suggestions for Enhancing the Efficiency of the Terms of Reference System

To address the issues discussed above, the author proposes the following improvements to Article 23 of the ICC Arbitration Rules (2021) to further enhance arbitration efficiency.

4.1.Clarifying the Definition of New Claims by Incorporating Case Law and Scholarly Opinions

Clarifying the definition of new claims requires distinguishing them from modifications to original claims. Based on case law and scholarly opinions, the fundamental criterion for this distinction is independence. German scholars suggest that the nature of a claim is determined by the combination of the cause of action and the prayer for relief [37]. The cause of action refers to the grounds for the claim, encompassing the full set of factual bases upon which the claim relies [38]. The prayer for relief can be defined as the precise instruction sought from the arbitrator regarding the requested outcome [39]. Therefore, distinguishing between a new claim and a modification of the original claim involves identifying and assessing these two elements. For a change in the cause of action to constitute a new claim, the underlying facts of the case must have fundamentally changed, and the new cause of action must be independent of the original cause of action. For changes to the prayer for relief, modifications that merely alter wording without changing meaning or intent, or that adjust the quantity or quality of the relief sought without creating independence from the original relief, do not constitute a new claim. Additionally, an analysis of arbitral awards from the ICC confirms this conclusion. If a newly introduced claim is independent of the original claim, it constitutes a new claim rather than a mere modification. For instance, a review of certain ICC cases [40] indicates that changes to the amount of relief sought do not constitute a new claim. Similarly, analysis of other ICC cases [41] reveals that introducing interest on damages based on the original relief does not constitute a new claim. Thus, when a new prayer for relief is accessory to, dependent on, or derived from the original claim, such changes do not constitute a new claim. By incorporating insights from case law and scholarly opinions, arbitration rules can be supplemented to define the nature of a new claim, clarifying that its cause of action or prayer for relief must be independent of the original claim.

4.2.Revising the Internal Logical Progression of the First Four Paragraphs of Article 23 of the ICC Arbitration Rules (2021)

As analyzed earlier, the logical layers established in Article 23 of the ICC Arbitration Rules (2021) based on whether new claims fall within the scope of the Terms of Reference lack substantive meaning. To address this, the author suggests two improvement paths: 1.Differentiating the criteria for new claims falling within the scope of the Terms of Reference and those falling outside but still permissible in arbitration. Based on logical progression, the first criterion should be stricter than the second. 2.Adopting a practical approach by eliminating the logical progression entirely. The rule could be rephrased as: "With reference to the original claims in the Terms of Reference, and based on the nature of the claim, the stage at which it is introduced, and other relevant factors, the arbitral tribunal shall determine whether the new claim may be included in the arbitration."

4.3.Incorporating Party Autonomy into the Rules for New Claims in Arbitration Proceedings

Party autonomy is the cornerstone of arbitration. Although the ICC is characterized by strong administrative authority, allowing parties to make decisions on procedural matters can enhance arbitration efficiency [42]. From a comparative perspective, Article 29 of the Spanish Arbitration Act (2003) stipulates that unless otherwise agreed by the parties, either party may amend or supplement their original claim during arbitration, unless the arbitrator considers such amendments to cause undue delay. Similarly, Article 24 of the DIAC Rules (2022) and Article 18 of the HKIAC Rules (2018) include similar provisions. Comparatively, the above rules give greater weight to party autonomy in deciding whether new claims can be included in arbitration. On proactivity: The ICC takes a more active role, with the tribunal acting as an assertive decision-maker to determine the nature of new claims. In contrast, institutions such as the DIAC adopt a more passive approach, serving as a gatekeeper to prevent delays while prioritizing party autonomy. On principles: The ICC rules generally prohibit the inclusion of new claims in ongoing arbitration, with exceptions for claims closely connected to the original claims. Conversely, the rules of the other institutions generally allow new claims, barring cases of malicious delay. The author suggests introducing a mechanism for party autonomy in the ICC rules. Specifically, if both parties reach a mutual agreement, new claims should be allowed in ongoing arbitration proceedings, rather than relying solely on the tribunal's discretion [43].

4.4.Enhancing Rule Granularity Through the Disclosure of Typical Arbitration Cases

Max Weber once stated that formally rational law is law that is predictable, and this predictability encompasses both legislative and judicial predictability [44]. Predictability in adjudication is essential for legal stability, and enhancing it is also critical for maintaining the authority of arbitration [45]. Some arbitration provisions lack sufficient granularity, requiring arbitrators to exercise discretion in their decisions. However, differences in arbitrators’ knowledge, cultural backgrounds, and value judgments may lead to varying outcomes for similar cases, resulting in inconsistent rulings. This undermines the predictability of judicial decisions and could even create opportunities for parties to bribe arbitrators, influencing arbitration outcomes [46].

As a rule, arbitration language should remain concise and precise. However, the non-public nature of international commercial arbitration awards often prevents parties and less experienced arbitrators from accessing resources that would help them understand arbitration rules. This leads to difficulties in interpreting and applying the rules, which in turn affects the efficiency of arbitration proceedings. Analyzing past decisions enables parties and arbitrators to understand which arguments are effective and how issues have been resolved. This not only enhances the persuasiveness of the parties’ arguments but also improves arbitration efficiency while reducing costs and time [47]. The author suggests that for key arbitration provisions lacking sufficient granularity or prone to disputes, the publication of typical cases can serve as a remedy. Due to the confidentiality requirements of international commercial arbitration [48], case disclosures should focus on the arbitrators’ reasoning and analysis under the arbitration rules, without revealing the identities of the parties involved. To address confidentiality concerns, parties could also be compensated with a certain amount of monetary compensation for allowing their cases to be used as precedents.

5.Conclusion

The core topic of this paper is the exploration of the Terms of Reference system in international commercial arbitration. Starting with the design objectives and significance of the Terms of Reference system, the paper highlights its value as a reference for improving arbitration rules in major international commercial arbitration institutions. From a dialectical perspective, the paper points out that while the system’s design has led to inefficiencies contrary to its intended purpose during actual operation, it remains an effective arbitration tool in specific situations when applied under the appropriate circumstances. Thus, the system holds both academic and practical significance for research and improvement. Focusing on Article 23 of the ICC Arbitration Rules, the paper adopts an interdisciplinary perspective from law and economics to analyze the efficiency of rule-making and operation. It acknowledges the advantages of the first three paragraphs of the provision in enhancing arbitration efficiency, while identifying issues in the fourth paragraph, such as the lack of a clear definition of new claims, insufficient criteria for determining whether new claims fall outside the Terms of Reference, and inconsistencies in the provision’s internal logic. Finally, the paper offers marginal improvement suggestions for these issues, demonstrating the practical significance and forward-looking nature of this research.

International commercial arbitration cases involve a wide and complex array of fields, including disputes in international goods transportation, international insurance, international investment, technology trade, international cooperation in natural resource development, and international engineering contracting. Different types of cases may encounter various obstacles during arbitration. This paper focuses exclusively on disputes that may arise from international sales contracts for goods to construct its research model, which presents certain limitations in scope. Additionally, the confidentiality requirements of international commercial arbitration create challenges in empirical research, leading to difficulties in data collection and limitations in the sample size and quality. Finally, comparative studies of the Terms of Reference system across arbitration rules of institutions other than the ICC are necessary to provide a more comprehensive foundation for potential improvements.

With the increase in global trade and investment, international commercial arbitration rules must further adapt to achieve greater internationalization and harmonization, accommodating the diverse legal cultures and business practices of different countries and regions. Improving arbitration rules will help create a clearer and more efficient arbitration process, thereby enhancing arbitration’s appeal as the preferred method for resolving international commercial disputes. China, playing a key role in the "Belt and Road Initiative," has an opportunity to establish and enhance international commercial arbitration centers [49]. It is foreseeable that China will strengthen coordination and cooperation with countries along the Belt and Road in terms of arbitration legal systems, fostering the establishment of more fair and efficient arbitration institutions and rule frameworks. The field of international commercial arbitration will continue to progress in areas such as rule internationalization and procedural efficiency, adapting to the development of the global economy and the deepening implementation of international cooperation initiatives like the Belt and Road.

References

[1]. ICC Arbitration Rules (2021). Retrieved from https://iccwbo.org/dispute-resolution/dispute-resolution-services/arbitration/rules-procedure/2021-arbitration-rules/

[2]. Wang, Z. X. (2005). On the Terms of Reference System in ICC Arbitration. Contemporary Law Review, (03), 144–152.

[3]. Quintard, F. A global comparison of international arbitration rules on new claims. Retrieved from https://www.pinsentmasons.com/out-law/analysis/global-comparison-international-arbitration-rules-new-claims

[4]. Cao, X. G. (2021). The Pursuit, Reflection, and Balance of Efficiency in International Investment Arbitration. Jiangxi Social Sciences, 41(04), 194–203.

[5]. Queen Mary University of London & White & Case. (2021). 2021 International Arbitration Survey: Adapting arbitration to a changing world. p. 23.

[6]. Carlevaris, A. (2019). Who (Still) Needs Terms of Reference? Les Cahiers de l’Arbitrage, 369, 384.

[7]. Zhang, L., & Dong, G. F. (2019). A Study on the Preliminary Objection Mechanism in ICSID Arbitration. Journal of International Economic Law, (01), 47–57.

[8]. Stipanowich, T. J. (2010). Arbitration: The New Litigation. University of Illinois Law Review, 1.

[9]. Drahozal, C. R. (2006). Arbitration Costs and Contingent Fee Contracts. Vanderbilt Law Review, 59, 729.

[10]. Drahozal, C. R., & Hylton, K. N. (2003). The Economics of Litigation and Arbitration: An Application to Franchise Contracts. The Journal of Legal Studies, 32(2), 549–584.

[11]. Lew, J. D. M., Mistelis, L. A., & Kröll, S. (2003). Comparative International Commercial Arbitration. Kluwer Law International.

[12]. Derains, Y., & Schwartz, E. A. (2005). A Guide to the ICC Rules of Arbitration.

[13]. Paoletti, M. (2019). Summaries and Issues in the ICC Terms of Reference: The Right Level of Case Management. Kluwer Arbitration Blog. Retrieved from https://arbitrationblog.kluwerarbitration.com/

[14]. Budnitz, M. E. (2004). The High Cost of Mandatory Consumer Arbitration. Law & Contemporary Problems, 67, 133.

[15]. Born, G. B. (2021). International Commercial Arbitration (3rd ed.).

[16]. Miles, W., & Speller, D. (2007). Security for Costs in International Arbitration: Emerging Consensus or Continuing Difference? The European Arbitration Review.

[17]. Webster, T. H., & Bühler, M. W. (2021). Handbook of ICC Arbitration: Commentary and Materials (5th ed.).

[18]. St. Antoine, T. J. (2007). Mandatory Arbitration: Why It’s Better Than It Looks. University of Michigan Journal of Law Reform, 41, 783.

[19]. Liu, X., & Feng, S. (2018). On the Conflict and Coordination Between Institutional Control and Party Autonomy in International Commercial Arbitration. Journal of Shanghai University of Political Science and Law (Legal Forum), 33(05), 1–13.

[20]. Timár, K. (2013). The Legal Relationship Between the Parties and the Arbitral Institution. ELTE Law Journal, 103, 121–122.

[21]. Yu, D. M., & Zhang, H. Y. (2024, April 20). Building a Global New Highland for International Commercial Arbitration. Rule of Law Daily, (001).

[22]. Ma, Z. H. (2014). Discussion on Procedural Orders in International Commercial Arbitration and the Necessity of Introducing Them into Chinese Arbitration Practice. Beijing Arbitration Journal, (02), 70–91.

[23]. Coase, R. H. (1988). The Nature of the Firm: Origin. Journal of Law, Economics, & Organization, 4(1), 3–17.

[24]. Drahozal, C. R. (2008). Arbitration Costs and Forum Accessibility: Empirical Evidence. University of Michigan Journal of Law Reform, 41, 813.

[25]. Coase, R. H. (1960). The Problem of Social Cost. Journal of Law and Economics, 3, 1–44.

[26]. Qian, H. D. (2002). The Theoretical Foundations of Law and Economics. Legal Research, (04), 3–17.

[27]. Bühler, M. (2004). Awarding Costs in International Commercial Arbitration: An Overview. ASA Bulletin, 22, 249.

[28]. Tang, S. X. (2019). Value Balancing and Institutional Construction of Early Disposition Mechanisms in International Commercial Arbitration. Wuhan University International Law Review, 3(02), 85–104.

[29]. Choi, S. J. (2003). The Problem with Arbitration Agreements. Vanderbilt Journal of Transnational Law, 36, 1233.

[30]. Strong, S. I. (2014). Beyond International Commercial Arbitration: The Promise of International Commercial Mediation. Washington University Journal of Law & Policy, 45, 10.

[31]. Zhang, W. X. (2001). Research on Legal Philosophy Categories. Beijing: China University of Political Science and Law Press.

[32]. Feng, Y. T. (2021). The Generalized Application and Value Balancing of Documentary Evidence Production Orders—Commenting on Article 47 of the New Civil Evidence Provisions. Journal of Zhejiang Gongshang University, (05), 128–140.

[33]. Webster, T. H., & Bühler, M. W. (2021). Handbook of ICC Arbitration: Commentary and Materials (5th ed.), 23–84.

[34]. Final Award in Case 13686 (Extract). (2014). ICC International Court of Arbitration Bulletin, 25(2).

[35]. Schwartz, E. A. (1992). Terms of Reference Under the 1998 ICC Arbitration Rules: A Practice Guide. ICC International Court of Arbitration Bulletin, 3(1), p. 35, para. 120.

[36]. ICC Case No. 6197 (1995), (1998). Yearbook Commercial Arbitration XXIII, p. 13. ICC Case No. 3267, (1987). Yearbook Commercial Arbitration XII, p. 87.

[37]. Berger, K. P., & Kellerhals, F. (2021). International and Domestic Arbitration in Switzerland (4th ed.), p. 440.

[38]. Berger, K. P., & Pfisterer, T. (2013). Article 20, Amendments to the Claim or Defence. In Zuberbühler, Müller, & Habegger (Eds.), Swiss Rules of International Arbitration: Commentary (2nd ed.), p. 228.

[39]. Perret, M. (1996). Les conclusions et les chefs de la demande dans l’arbitrage international. ASA Bulletin, 1, p. 7.

[40]. ICC Cases Nos. 6097, 6763, 7076, 7210, 7213, 8268.

[41]. ICC Cases Nos. 10007, 10985, 11424.

[42]. Blavi, F., & Vial, G. (2016). The Burden of Proof in International Commercial Arbitration: Are We Allowed to Adjust the Scales? Hastings International & Comparative Law Review, 39, 41.

[43]. Kassis, A. (2006). L'autonomie de l'arbitrage commercial international: le droit français en question. L'autonomie de l'arbitrage commercial international, 1–576.

[44]. Lin, Y. T. (2023). Are Arbitration Precedents a Fallacy? Comparative Studies and Jurisprudential Reflections on the Debate on "Arbitration Precedents"—Implications for Chinese Arbitration. Beijing Arbitration Journal, (01), 85–115.

[45]. Wang, L. M. (2015). The Predictability of Judicial Decisions. Contemporary Guizhou, (38), 63.

[46]. Sayed, A. (2001). Question de la Corruption dans l'Arbitrage Commercial International: Inventaire des Solutions, La. ASA Bulletin, 19, 653.

[47]. Walker, J., & Jones, D. (2007). Transparency and Efficiency in International Commercial Arbitration.

[48]. Müller, C. (2005). Confidentiality in International Commercial Arbitration: An Illusion? ASA Bulletin, 23, 216.

[49]. Zhang, W., & Li, Z. D. (2023, September 27). 55 International Arbitration Institutions Join the "Belt and Road" Arbitration Cooperation Mechanism. Rule of Law Daily, (008).

Cite this article

Mao,P. (2024). Viewing the Terms of Reference System from the Perspective of Efficiency of International Commercial Arbitration. Lecture Notes in Education Psychology and Public Media,68,58-70.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Social Psychology and Humanity Studies

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. ICC Arbitration Rules (2021). Retrieved from https://iccwbo.org/dispute-resolution/dispute-resolution-services/arbitration/rules-procedure/2021-arbitration-rules/

[2]. Wang, Z. X. (2005). On the Terms of Reference System in ICC Arbitration. Contemporary Law Review, (03), 144–152.

[3]. Quintard, F. A global comparison of international arbitration rules on new claims. Retrieved from https://www.pinsentmasons.com/out-law/analysis/global-comparison-international-arbitration-rules-new-claims

[4]. Cao, X. G. (2021). The Pursuit, Reflection, and Balance of Efficiency in International Investment Arbitration. Jiangxi Social Sciences, 41(04), 194–203.

[5]. Queen Mary University of London & White & Case. (2021). 2021 International Arbitration Survey: Adapting arbitration to a changing world. p. 23.

[6]. Carlevaris, A. (2019). Who (Still) Needs Terms of Reference? Les Cahiers de l’Arbitrage, 369, 384.

[7]. Zhang, L., & Dong, G. F. (2019). A Study on the Preliminary Objection Mechanism in ICSID Arbitration. Journal of International Economic Law, (01), 47–57.

[8]. Stipanowich, T. J. (2010). Arbitration: The New Litigation. University of Illinois Law Review, 1.

[9]. Drahozal, C. R. (2006). Arbitration Costs and Contingent Fee Contracts. Vanderbilt Law Review, 59, 729.

[10]. Drahozal, C. R., & Hylton, K. N. (2003). The Economics of Litigation and Arbitration: An Application to Franchise Contracts. The Journal of Legal Studies, 32(2), 549–584.

[11]. Lew, J. D. M., Mistelis, L. A., & Kröll, S. (2003). Comparative International Commercial Arbitration. Kluwer Law International.

[12]. Derains, Y., & Schwartz, E. A. (2005). A Guide to the ICC Rules of Arbitration.

[13]. Paoletti, M. (2019). Summaries and Issues in the ICC Terms of Reference: The Right Level of Case Management. Kluwer Arbitration Blog. Retrieved from https://arbitrationblog.kluwerarbitration.com/

[14]. Budnitz, M. E. (2004). The High Cost of Mandatory Consumer Arbitration. Law & Contemporary Problems, 67, 133.

[15]. Born, G. B. (2021). International Commercial Arbitration (3rd ed.).

[16]. Miles, W., & Speller, D. (2007). Security for Costs in International Arbitration: Emerging Consensus or Continuing Difference? The European Arbitration Review.

[17]. Webster, T. H., & Bühler, M. W. (2021). Handbook of ICC Arbitration: Commentary and Materials (5th ed.).

[18]. St. Antoine, T. J. (2007). Mandatory Arbitration: Why It’s Better Than It Looks. University of Michigan Journal of Law Reform, 41, 783.

[19]. Liu, X., & Feng, S. (2018). On the Conflict and Coordination Between Institutional Control and Party Autonomy in International Commercial Arbitration. Journal of Shanghai University of Political Science and Law (Legal Forum), 33(05), 1–13.

[20]. Timár, K. (2013). The Legal Relationship Between the Parties and the Arbitral Institution. ELTE Law Journal, 103, 121–122.

[21]. Yu, D. M., & Zhang, H. Y. (2024, April 20). Building a Global New Highland for International Commercial Arbitration. Rule of Law Daily, (001).

[22]. Ma, Z. H. (2014). Discussion on Procedural Orders in International Commercial Arbitration and the Necessity of Introducing Them into Chinese Arbitration Practice. Beijing Arbitration Journal, (02), 70–91.

[23]. Coase, R. H. (1988). The Nature of the Firm: Origin. Journal of Law, Economics, & Organization, 4(1), 3–17.

[24]. Drahozal, C. R. (2008). Arbitration Costs and Forum Accessibility: Empirical Evidence. University of Michigan Journal of Law Reform, 41, 813.

[25]. Coase, R. H. (1960). The Problem of Social Cost. Journal of Law and Economics, 3, 1–44.

[26]. Qian, H. D. (2002). The Theoretical Foundations of Law and Economics. Legal Research, (04), 3–17.

[27]. Bühler, M. (2004). Awarding Costs in International Commercial Arbitration: An Overview. ASA Bulletin, 22, 249.

[28]. Tang, S. X. (2019). Value Balancing and Institutional Construction of Early Disposition Mechanisms in International Commercial Arbitration. Wuhan University International Law Review, 3(02), 85–104.

[29]. Choi, S. J. (2003). The Problem with Arbitration Agreements. Vanderbilt Journal of Transnational Law, 36, 1233.

[30]. Strong, S. I. (2014). Beyond International Commercial Arbitration: The Promise of International Commercial Mediation. Washington University Journal of Law & Policy, 45, 10.

[31]. Zhang, W. X. (2001). Research on Legal Philosophy Categories. Beijing: China University of Political Science and Law Press.

[32]. Feng, Y. T. (2021). The Generalized Application and Value Balancing of Documentary Evidence Production Orders—Commenting on Article 47 of the New Civil Evidence Provisions. Journal of Zhejiang Gongshang University, (05), 128–140.

[33]. Webster, T. H., & Bühler, M. W. (2021). Handbook of ICC Arbitration: Commentary and Materials (5th ed.), 23–84.

[34]. Final Award in Case 13686 (Extract). (2014). ICC International Court of Arbitration Bulletin, 25(2).

[35]. Schwartz, E. A. (1992). Terms of Reference Under the 1998 ICC Arbitration Rules: A Practice Guide. ICC International Court of Arbitration Bulletin, 3(1), p. 35, para. 120.

[36]. ICC Case No. 6197 (1995), (1998). Yearbook Commercial Arbitration XXIII, p. 13. ICC Case No. 3267, (1987). Yearbook Commercial Arbitration XII, p. 87.

[37]. Berger, K. P., & Kellerhals, F. (2021). International and Domestic Arbitration in Switzerland (4th ed.), p. 440.

[38]. Berger, K. P., & Pfisterer, T. (2013). Article 20, Amendments to the Claim or Defence. In Zuberbühler, Müller, & Habegger (Eds.), Swiss Rules of International Arbitration: Commentary (2nd ed.), p. 228.

[39]. Perret, M. (1996). Les conclusions et les chefs de la demande dans l’arbitrage international. ASA Bulletin, 1, p. 7.

[40]. ICC Cases Nos. 6097, 6763, 7076, 7210, 7213, 8268.

[41]. ICC Cases Nos. 10007, 10985, 11424.

[42]. Blavi, F., & Vial, G. (2016). The Burden of Proof in International Commercial Arbitration: Are We Allowed to Adjust the Scales? Hastings International & Comparative Law Review, 39, 41.

[43]. Kassis, A. (2006). L'autonomie de l'arbitrage commercial international: le droit français en question. L'autonomie de l'arbitrage commercial international, 1–576.

[44]. Lin, Y. T. (2023). Are Arbitration Precedents a Fallacy? Comparative Studies and Jurisprudential Reflections on the Debate on "Arbitration Precedents"—Implications for Chinese Arbitration. Beijing Arbitration Journal, (01), 85–115.

[45]. Wang, L. M. (2015). The Predictability of Judicial Decisions. Contemporary Guizhou, (38), 63.

[46]. Sayed, A. (2001). Question de la Corruption dans l'Arbitrage Commercial International: Inventaire des Solutions, La. ASA Bulletin, 19, 653.

[47]. Walker, J., & Jones, D. (2007). Transparency and Efficiency in International Commercial Arbitration.

[48]. Müller, C. (2005). Confidentiality in International Commercial Arbitration: An Illusion? ASA Bulletin, 23, 216.

[49]. Zhang, W., & Li, Z. D. (2023, September 27). 55 International Arbitration Institutions Join the "Belt and Road" Arbitration Cooperation Mechanism. Rule of Law Daily, (008).