1. Introduction

Research has point out that targets (who are rejected or excluded) of social exclusion suffer a variety of negative effects [1]: Self-esteem [2,3], Meaningful existence [4], Belongingness [5], and Control [6]. The Need-Threat Model [7]and Sociometer Hypothesis [8] postulate that exclusion undermines self-esteem. Self-esteem is a measurement of relational value: how much others value the relationship. Therefore, when a person is socially excluded, he or she will think that the other party does not attach great importance to the relationship, so he or she will refuse the social request.

However, although most people are aware of the psychological damage caused by rejection or social exclusion to the people in real life, social rejection is inevitable. For example, when you receive an invitation from two friends at the same time. One invites you to his child's birthday party and the other invites you to her wedding. However, the two events were held on the same day. At this time, you will face a choice: accept the invitation to the birthday party and refuse the invitation to the wedding or accept the invitation to the wedding and refuse the invitation to the birthday party. Both options will lead to social exclusion of one party's invitees. In this case, you want to minimize the damage to the rejected party and maintain your good reputation. It is particularly important to choose an appropriate way of rejection.

A new taxonomy is built about the types of social exclusion by conceptualizing social exclusion to the degree it includes clear [9]: explicit rejection (explicit verbal expression, clearly stating no), ostracism (ignoring and lack of communication), and ambiguous rejection (contradict and unclear communication) [10]. Responsive Theory of Exclusion differs from existing theories because it considers both the sources and targets of social exclusion and indicates that both parties will feel better if sources are responsive to targets’ needs.

Figure 1: Classification Steps

Rejection Sensitivity (RS) was interpreted as the processing tendency of anxious expectation, easily perceived and overreaction to rejection. According to RS model, people with high RS level not only expect to be rejected by others, but also pay high attention and anxiety to the actual occurrence of rejection. Therefore, the anxiety expectation of rejection is the core component of high RS. More specifically, people with high RS level tend to see the attitude of intentional rejection more easily in the ambiguous or negative behaviors of communication and romantic partners. For example, high RS people in a new relationship may interpret their partner's apathy as intentional rejection and injury [11,12].

Although a mountain of evidence supports for the harmful effect of exclusion on targets’ self-esteem, there are few research involve how individual differences in rejection sensitivity influence self-esteem in different social exclusions. Different types of social exclusion will affect different levels of self-esteem, and the uniqueness of exclusion will also reflect the differences of individual sensitivity. Through this study, we can further refine the relationship between social exclusion and change in self-esteem. By understanding the characteristics of different groups of people, the study provides sources (who reject or exclude others) a reference method which will hurt others' self-esteem in the least way when they must refuse others in the future.

2. Present Work

We hope to further explore the influence of individual rejection sensitivity in three different social exclusion phenomena. To achieve this goal, we designed three questionnaires, each one containing one of the three different social exclusion phenomena. In all the questionnaires, the subjects are excluded. We also designed a test about explicit self-esteem. The subjects were asked to do it before and after being exposed in social exclusion occasion. After collecting all the data, we compared the changes of self-esteem of people with low rejection sensitivity level and high rejection sensitivity level under three different kinds of social exclusion.

3. Experiment

3.1. Experimental design

Participants. 79 individuals participated in a two-part study voluntarily. Of all the 79 participants (N=71, 42 females), we collected their answer individually. To reduce the intervene of confounding factors as much as possible and obtain more samples, the subjects are selected from the same culture (China). All the participants are between the age of 18-50.

Procedures. The experiment was divided into two parts. In the first part, we asked all the participants to do a Rejection Sensitivity Questionnaire [13]and an explicit self-esteem measurement first. The experiment involved two anonymous questionnaires, and all the subjects were asked to provide certain identity information so that the researchers could correspond the two experimental data one by one.

3.2. Measurements

Measure 1. In the rejection sensitivity test, each of the questions described some situations that people may face in their real life. For each question, the examinees must assume that they were in this situation and indicated their level of rejection concern about the possibility of a rejection (1 = not anxious, 5 = very anxious) and acceptance expectancy (1 = very likely, 5 = very unlikely) in seven different occasions. We calculated the score of rejection sensitivity by multiplying the level of rejection concern by the reverse of expectations of rejection and took the mean of the resulting 7 scores to obtain the overall rejection sensitivity for each participant. In the sample the mean RSQ score was 2.69 (SD = 3.25). Based on the result, we divided participants into two categories: High Rejection sensitivity group (S >= 2.69) and Low Rejection sensitivity group (S< 2.69).

Measure 2. In the explicit self-esteem test, participants were asked ten explicit self-esteem questions and rated the self-esteem level for each question from 1 (extremely low) to 10 (extremely high). We calculated the score of explicit self-esteem by adding up the score of each question. The test result showed that the mean of the sample’s explicit self-esteem score was 66.46 (SD=14.48).

Then, 15 days later, we again invited participants to one of the three social exclusion questionnaires randomly. Under the three social exclusion phenomena that we have classified, each one described the same specific scene in which participants were attending a weekend party. In the process of questionnaire, each participant was put into a social exclusion event where participants found a stranger, they would like to build relationship with and tried to invite the stranger for a separate two-people dinner. They were in the state of exclusion—participants were rejected by the stranger. However, the rejection was different in three categories. In the explicit exclusion scenario, participants were rejected by the stranger who used direct and clear verbal message to tell the participants that he or she was not interested in hanging out with participants alone; in the ambiguous exclusion scenario, participants were rejected by the stranger expressing contradict message: saying he or she thought was a good advice but would like to think twice; in the ostracism scenario, the stranger totally ignored the participants’ invitation and continued to have conversation with others in the party. After browsing the specific scene, participants were asked how they felt about being excluded, how they felt about the excluder, and how they felt about their change in self-esteem (self-report/explicit self-esteem). After they completed the questionnaire, each participant was asked to complete the same explicit self-esteem test they did 15 days ago. At the end of this part of the test, we also collected everyone's data.

We compared each person's two explicit self-esteem tests before and after the questionnaire and calculated the change of each person's self-esteem. We also calculated the average self-esteem change of person in each category according to the grouping of two level of rejection sensibility and three different social exclusions. At the same time, we compared which exclusion phenomenon had the greatest impact on self-esteem and which exclusion phenomenon had the least impact on self-esteem in both high and low rejection sensitivity groups.

4. Data Analytic Approach.

Through the analysis of the data, we hope that we can not only know the self-esteem changes of people in the face of three kinds of social exclusion phenomena under common circumstances (regardless of personal differences), but also find the most suitable situation of each kind of rejection sensitive people in the face of social exclusion through detailed classification.

5. Results

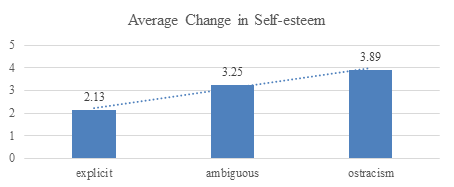

Aim 1. Firstly, according to the classification of three different types of social exclusion, we found that whether participants belong to high rejection sensitivity group or low rejection sensitivity group, it was clear that explicit rejection was the social exclusion with the smallest change in self-esteem score (N=23, Average Change in Self-esteem Score=2.13), ambiguous rejection was the second (N=28, Average Change in Self-esteem Score=3.25), and ostracism was the social exclusion with the greatest impact on self-esteem score (N=28, Average Change in Self-esteem Score=3.89).

Figure 2: Average Change in Self-esteem in different social exclusions

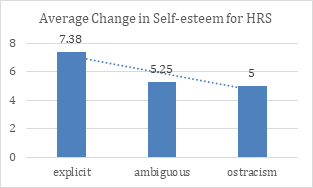

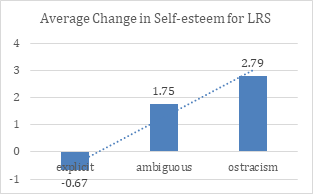

Aim 2. We calculated the average change in self-esteem score of high rejection sensitivity group and low rejection sensitivity group in three social exclusions as a whole and separately. We found that no matter what kind of social exclusion, the change of self-esteem score of participants with high rejection sensitivity (N=34, Average Change in Self-esteem Score=5.65) was always greater than that of participants with low rejection sensitivity (N=44, Average Change in Self-esteem Score=1.27). The population with low rejection sensitivity conformed to the overall trend, that was, the change was the lowest in the explicit social exclusion phenomenon (N=15, Average Change in Self-esteem Score=-0.67) and was the highest in the ostracism social exclusion phenomenon (N=14, Average Change in Self-esteem Score=2.79). However, for participants with high rejection sensitivity, they changed the most in the explicit social exclusion (N=8, Average Change in Self-esteem Score=7.38), the second in the ambiguous social exclusion (N=12, Average Change in Self-esteem Score=5.25), and the least in the ostracism social exclusion (N=14, Average Change in Self-esteem Score=5).

Figure 3 Average Change in Self-esteem for HRS

Figure 4 Average Change in Self-esteem for LRS

6. Conclusion

In this study, we aimed find out the self-esteem changes of different rejection sensitive groups in the face of different social exclusion phenomena, so as to provide reference for predicting people's behavior in the future. In this two-part study, participants were asked to complete a rejection sensitivity questionnaire, two identical explicit self-esteem tests, and a social exclusion questionnaire. Base on the statistic we collected, we not only reverified William's Responsive theory of social exclusion, but also found out the rules of different rejection sensitive people's self-esteem changes in the face of social exclusion: in general terms, targets’ self-esteem will not suffer a huge blow if sources use clear verbal communication to reject and will suffer a lot if sources choose to ignore the targets. But this rule may not suit for people with high rejection sensitivity since they will experience anxiety and pain during the rejection. It is better to express rejection euphemistically to allowed high rejection sensitivity targets to do enough mental construction and self-comfort beforehand.

This study was the first time a study to analyze the change of self-esteem in the face of different social exclusion from the perspective of individual difference (rejection sensitivity). Through the study of individual differences, we could more clearly understand the causes, process and results of self-esteem changes in the face of social exclusion.

However, there were some deficiencies in the research. Firstly, through the online questionnaire to show people in social exclusion phenomenon was different from people in real social exclusion phenomenon. If the participants only assumed that they were excluded, their feelings of being excluded would be weakened, so their influence on self-esteem would also be weakened. In the future research, if we can get rid of our own limitations, put the research into the laboratory to simulate the real social exclusion, and let the subjects participate, the accuracy of the results will be improved. Secondly, this research only studied the individual difference of rejection sensitivity, and there were some other individual differences that could be considered: attachment styles and tendency in defensive orientation and protective orientation. Finally, beyond the individual and the dyad, it is also important to consider how culture may impact the interpersonal nature of social exclusion. In conclusion, future research can be conducted on different individual differences or cultural differences, and further search for the relationship between self-esteem changes and these variables.

References

[1]. Baumeister, R. F., Twenge, J. M., and Nuss, C. K. (2002). Effects of social exclusion on cognitive processes: anticipated aloneness reduces intelligent thought. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 83, 817–827. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.83.4.817

[2]. Leary, M. R., Tambor, E. S., Terdal, S. K., and Downs, D. L. (1995). Self-esteem as an interpersonal monitor: the sociometer hypothesis. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 68, 518–530. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.68.3.518

[3]. Leary, M. R. (1990). Responses to social exclusion: social anxiety, jealousy, loneliness, depression, and low self-esteem. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 9, 221–229. doi: 10.1521/jscp.1990.9.2.221

[4]. Williams, K. D., and Sommer, K. L. (1997). Social ostracism by coworkers: does rejection lead to loafing or compensation? Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 23, 693–706. doi: 10.1177/0146167297237003

[5]. Zadro, L., Williams, K. D., and Richardson, R. (2004). How low can you go? Ostracism by a computer is sufficient to lower self-reported levels of belonging, control, self-esteem, and meaningful existence. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 40, 560–567. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2003.11.006

[6]. Warburton, W. A., Williams, K. D., and Cairns, D. R. (2006). When ostracism leads to aggression: the moderating effects of control deprivation. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 42, 213–220. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2005.03.005

[7]. Williams, K. D. (2009). “Ostracism: a temporal need-threat model,” in Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, Vol. 41, ed. M. Zanna (New York, NY: Academic Press), 279–314.

[8]. Leary, M. R., and Downs, D. (1995). “Interpersonal functions of the self-esteem motive: the self- esteem system as a sociometer,” in Efficacy, Agency, and Self-Esteem, ed. M. Kernis (New York, NY: Plenum Press).

[9]. Freedman, G., Williams, K. D., & Beer, J. S. (2016). Softening the blow of social exclusion: The responsive theory of social exclusion. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 1570

[10]. Freedman G, Williams KD and Beer JS (2016) Softening the Blow of Social Exclusion: The Responsive Theory of Social Exclusion. Front. Psychol. 7:1570. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01570

[11]. Downey G, Feldman S. Implications of rejection sensitivity for intimate relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1996;70(6):1327–1343.

[12]. Özlem Ayduk, Anett Gyurak, and Anna Luerssen (2008) Individual differences in the rejection-aggression link in the hot sauce paradigm: The case of Rejection Sensitivity. J Exp Soc Psychol. 2008 May 1; 44(3): 775–782.

[13]. Berenson, K. R., Gyurak, A., Downey, G., Ayduk, O., Mogg, K., Bradley, B., & Pine, D. (2009). Rejection sensitivity and disruption of attention by social threat cues. Journal of Research in Personality, 43, 1064–1072.

Cite this article

Shi,Y. (2023). Individual Differences in Self-Esteem in Response to Different Forms of Social Exclusion. Lecture Notes in Education Psychology and Public Media,2,58-63.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Educational Innovation and Philosophical Inquiries (ICEIPI 2022), Part I

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Baumeister, R. F., Twenge, J. M., and Nuss, C. K. (2002). Effects of social exclusion on cognitive processes: anticipated aloneness reduces intelligent thought. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 83, 817–827. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.83.4.817

[2]. Leary, M. R., Tambor, E. S., Terdal, S. K., and Downs, D. L. (1995). Self-esteem as an interpersonal monitor: the sociometer hypothesis. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 68, 518–530. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.68.3.518

[3]. Leary, M. R. (1990). Responses to social exclusion: social anxiety, jealousy, loneliness, depression, and low self-esteem. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 9, 221–229. doi: 10.1521/jscp.1990.9.2.221

[4]. Williams, K. D., and Sommer, K. L. (1997). Social ostracism by coworkers: does rejection lead to loafing or compensation? Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 23, 693–706. doi: 10.1177/0146167297237003

[5]. Zadro, L., Williams, K. D., and Richardson, R. (2004). How low can you go? Ostracism by a computer is sufficient to lower self-reported levels of belonging, control, self-esteem, and meaningful existence. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 40, 560–567. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2003.11.006

[6]. Warburton, W. A., Williams, K. D., and Cairns, D. R. (2006). When ostracism leads to aggression: the moderating effects of control deprivation. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 42, 213–220. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2005.03.005

[7]. Williams, K. D. (2009). “Ostracism: a temporal need-threat model,” in Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, Vol. 41, ed. M. Zanna (New York, NY: Academic Press), 279–314.

[8]. Leary, M. R., and Downs, D. (1995). “Interpersonal functions of the self-esteem motive: the self- esteem system as a sociometer,” in Efficacy, Agency, and Self-Esteem, ed. M. Kernis (New York, NY: Plenum Press).

[9]. Freedman, G., Williams, K. D., & Beer, J. S. (2016). Softening the blow of social exclusion: The responsive theory of social exclusion. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 1570

[10]. Freedman G, Williams KD and Beer JS (2016) Softening the Blow of Social Exclusion: The Responsive Theory of Social Exclusion. Front. Psychol. 7:1570. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01570

[11]. Downey G, Feldman S. Implications of rejection sensitivity for intimate relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1996;70(6):1327–1343.

[12]. Özlem Ayduk, Anett Gyurak, and Anna Luerssen (2008) Individual differences in the rejection-aggression link in the hot sauce paradigm: The case of Rejection Sensitivity. J Exp Soc Psychol. 2008 May 1; 44(3): 775–782.

[13]. Berenson, K. R., Gyurak, A., Downey, G., Ayduk, O., Mogg, K., Bradley, B., & Pine, D. (2009). Rejection sensitivity and disruption of attention by social threat cues. Journal of Research in Personality, 43, 1064–1072.