1. Introduction

China’s public interest litigation system is a form of legal action aimed at protecting public interest, primarily covering fields such as ecological environment protection, food and drug health, cultural heritage preservation, etc. In a nutshell, the PIL regime allows the procuratorate or authorised social organisations to initiate lawsuits against wrongdoers who have harmed the public interest when violating certain laws. The concept of public interest litigation was first introduced in the civil procedure law [1]. Then, the Standing Committee of the National People's Congress authorized a pilot project for the procuratorial organs to initiate PILs in the fields of ecological environment and food and drug safety in 2015 [2]. In 2017, the PIL regime was expanded to cover the following areas: protection of state-owned property, and transfer of the right to use state-owned land cases as well [3]. In subsequent years, the regime has further expanded to protect the reputation of heroes and martyrs [4], to protect the rights and interests of minors [5], to protect personal information security [6], to regulate network fraud [7], to protect the rights and interests of disabilities [8], and to protect cultural heritage [9], etc.

PIL, as an important mechanism in China’s modern legal system, safeguards public interests, supplementing traditional public and private enforcement. On the one hand, it breaks through the limitation of individual litigation, allowing procuratorial organs, social organizations and other subjects to represent unspecified public rights protection, and solving the dilemma of no prosecution for group damages such as environmental pollution or food and drug safety. On the other hand, PIL can achieve the dual effects of public welfare restoration and system improvement, the judgment not only requires compensation, but also promotes the rectification of enterprises involved and the improvement of government supervision, forming a long-term mechanism for social governance.

Despite the benefits of PILs, scholars have identified room for improving the PIL system mainly from three perspectives: litigation subjects, preventive measures, and punitive damages. First, regarding litigation subjects, He and Jia argued that there is often an overlap between civil and administrative public interest litigation in practice, which can lead to disputes over the qualifications of litigation subjects, unclear applicable conditions, ambiguous jurisdiction levels of courts, and overlapping methods of assuming restoration responsibilities [10]. Second, regarding preventive measures, Wang proposed clarifying the criteria for identifying major risks, improving the methods of responsibility assumption, and strengthening the connection between preventive litigation and environmental administrative law enforcement [11], Lin and Wang suggested to relax the scope of subject qualification, define the criteria for accepting cases, and specify the allocation path of the burden of proof [12]. Third, regarding punitive damages, Wang examined whether the lawbreaker is obligated to pay punitive damages through different elements, such as consideration of the defendant's subjective malice, the actual damage suffered by the victim, the interests obtained by the infringer due to improper acts and the financial situation of the defendant's liability for compensation [13]. Wang and Guo also believe that it is necessary to determine whether the lawbreaker should bear punitive damages liability based on whether they have subjective intent [14].

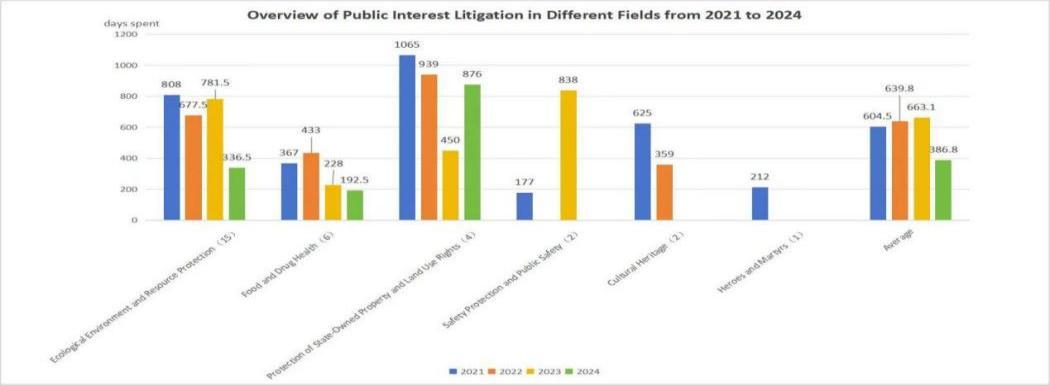

The literature on the PIL system not only deepens our understanding of the relatively new form of legal enforcement but also points out potential directions to perfect the system. Nevertheless, there is one important aspect of the PIL system that has yet to be studied, that is the length and, hence, efficiency of PILs. The author has randomly collected 30 PIL cases decided between 2021 and 2024 from China Judgement Online and Judicial Cases Database of China. Then, the author summarized the length of time it took to resolve these cases in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1: reveals that the ecological environment field had the longest processing time, about 650.9 days on average, while the food and drug health field, with the shortest time consumption, about 305.1 days on average. Across different areas of the cases, the average trial duration of PIL cases is around two years. Specific cases could last way longer than that, such as the “Yunnan Green Peacock Case” [15] took 4 years, and the “Changzhou Dudi Case” [16] took 5 years. The long time it takes to resolve a PIL could have negative implication for the public. For example, before a case is resolved, its harm would be prolonged or even aggravated.

Figure 1: Overview of public interest litigation in different fields from 2021 to 2024

In light of the above, as a first attempt, this article first investigates the reasons for the long duration of PIL. Then, it explores the harm of an inefficient PIL system and suggests ways to improve the system.

2. Reasons for slow responses in public interest litigations

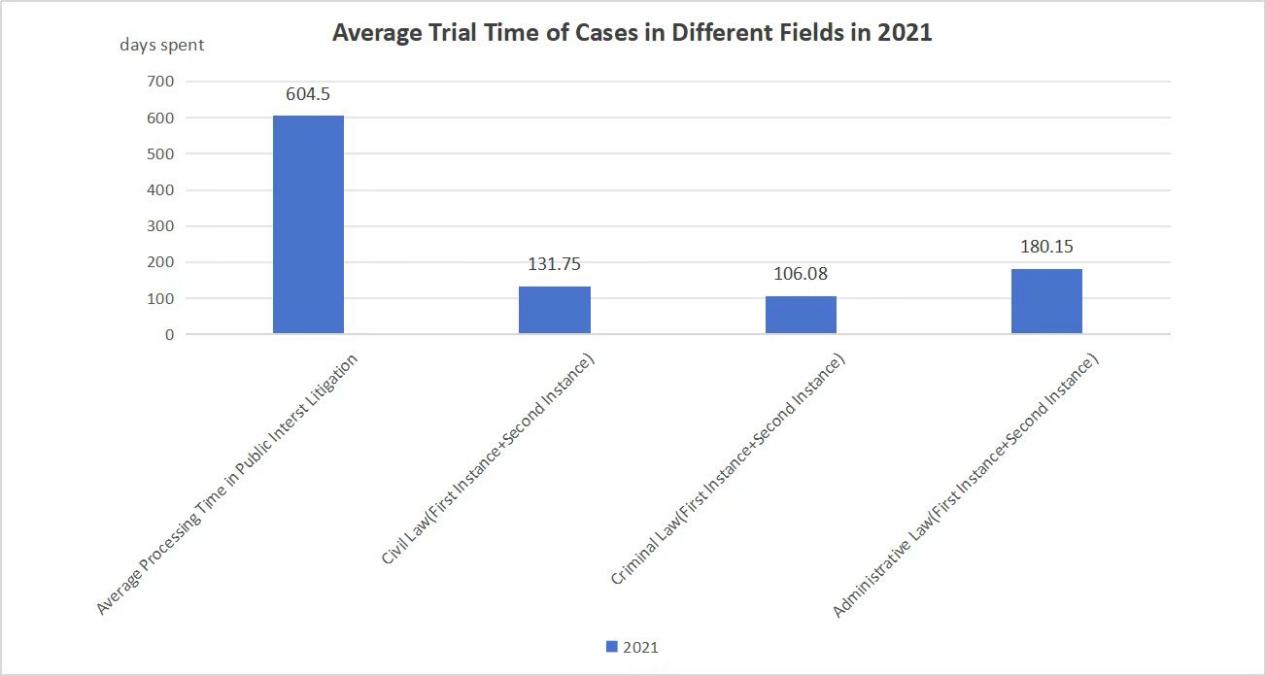

Figure 2: Average trial time of cases in different fields in 2021

To understand the lengthiness of PILs, one could compare their duration to the duration of conventional public enforcement. Figure 2 presents the average trial time of cases in different fields in 2021. It reveals that the adjudication period for PIL significantly exceeds ordinary judicial procedures. On the one hand, PILs with an average duration of 604.5 days in 2021 (10 cases). On the other hand, criminal cases, which includes both the first instance and the second instance procedures, averaged 106.08 days, civil cases 131.75 days, and administrative cases 180.15 days [17]. Both the PILs and criminal cases used in the above comparison are handled by the procuratorate. Therefore, the difference in their duration is unlikely to be attributed to institutional distinction. Instead, the inefficiency in PIL is likely to stem from the nature or special features of the PIL regimes. Below, I will provide three plausible explaintions to the long duration of PILs.

2.1. Acquisition and application of evidence

The practical low effectiveness of public interest litigation in China can be attributed to issues related to the acquisition and application of evidence in PILs.

PIL regime in China has an unreasonable allocation of the burden of proof, which stems from the disconnect between general civil litigation rules and the special needs of PIL. The particularity of PIL lies in that it needs to be filed by qualified subjects, such as procuratorial organs and social organizations on behalf of unspecified public interests. Without having a direct interest in the case, aiming at solving systematic social problems such as environmental damage or infringement of consumers' rights and interests, and take the public interest as the priority over individual compensation as the goal. The current Civil Procedure Law mechanically applies the principle of “he who asserts must prove,” requiring PIL plaintiffs to bear the same burden of proof as in ordinary civil cases, while overlooking the essential differences in the inherent biases of evidence, technical complexity, and the public interest attributes inherent to public interest litigation. This contradiction erupted prominently in the public interest litigation case regarding chrome slag pollution in Qujing, Yunnan: In 2011, the environmental organization Friends of Nature sued Yunnan Luliang Chemical for illegally dumping chrome slag that polluted the Nanpan River, claiming ecological compensation of 10 million yuan. However, it was unable to bear the 7 million yuan cost of the environmental damage assessment, which was far exceeding its annual operating expenses. This has in turn led to a nine-year stagnation of the case, ultimately concluding hastily with a settlement of 3.08 million yuan [18]. This case exposes systemic flaws regarding evidence in PIL. First, plaintiffs are compelled to assume the responsibility for obtaining key evidence that should be within the control of the defendant or public authorities. Even worse, it is later reported that the defendant companies have concealed the pollution data and their security guards have seized plaintiff investigators’ cameras to delete evidence [19]. Moreover, the plaintiff was required to prepare and submit a report which assesses the causation between the alleged wrongful conduct of the defendant and the harm done to the public (hereinafter “causality assessments”). Such causality assessments must conducted by specialized institutions, and the assessment fees charged are proportionally to the litigation amount. This creates a paradox where the higher the litigation amount, the more unbearable the cost of proof to the plaintiff. Secondly, the Ministry of Justice has designated 141 post-payment assessment institutions by 2024, (normally, when the plaintiff prevail in trail he cost of the appraisal report will be borne by the losing party, that is, the defendant. On the contrary, if the assessment results do not align with the plaintiff's claims, the costs will still be borne by the plaintiff.) This effectively shifts the risks of scientific disputes onto the initiators of PILs, forcing many cases to be voluntarily withdrawn or their demands reduced due to economic risks. The high cost is not a problem for the procuratorial organs, but the lawsuit that might have been filed by non-governmental organizations (NGO), because of the fear of the financial burden, will make the NGOs that have some evidence give up the lawsuit. As a result, if cases that damages the public interest must be solved, the procuratorate needs to collect evidence again, which slows down the case that can be solved at a faster speed.

Another contradiction lies in the limited evidence sharing system between different government agencies. Evidence sharing between administrative organs and judicial organs is still superficial. The collection procedures of written evidence are complicated, such as drawings and files, which need to be collected by case handlers from different companies and institutions, and need to be approved and reported at different levels before obtaining evidence. The phenomenon that evidence cannot be shared persists, because the legislation fails to compile mandatory cross-departmental evidence sharing rules, including the standards for mutual recognition of evidence, the timetable for information disclosure and the punishment for violators. Consequently, in order to make a reasonable judgment, judicial workers can only spend extra time to review or set standards, which will undoubtedly lead to further extension of PIL time.

2.2. Jurisdictional issue

By nature, PIL cases affect a large population, covering multiple cities or even provinces in the country. Therefore, multiple local procuratorates could have jurisdiction to handle a PIL case. However, the law does not specify which local procuratorate is primarily responsible for the case. This ambiguity could result in the delay of legal enforcement. The slow progress caused by the jurisdiction ambiguity was evident in the public interest litigation case of the Longshan County Bureau of Natural Resources. Since Longshan County and Huayuan County belong to different administrative regions, the Longshan County People's Procuratorate should have filed a lawsuit with the local court of Longshan County in accordance with the general principle of administrative litigation jurisdiction. However, according to the Hunan Provincial High People's Court's implementation plan for centralized jurisdiction, the latter has jurisdiction. This requires the former to transfer the case to the latter, and then the latter to file a lawsuit with the local people's court, which increases the time cost of case transfer and jurisdictional connection [20]. Another contradiction lies in the jurisdiction of cross-regional cases. During the trial of the case, the inter-provincial differences in ecological restoration standards, local bargaining on the sharing of restoration costs and obstacles to the implementation of the restoration plan will also slow down the whole litigation process.

2.3. Tension between legislative frameworks and practical implementation

Another reason that prolonged public interest cases might be a lack of legal clarity. Note that the time required to resolve a case not only includes the time of trial, but also the time to enforce a court judgement. The People's Procuratorate of Rongjiang County, Guizhou Province urged the protection of traditional villages [21], is a microcosm of such issues: the government of Zaima Town has been entrusted by Environmental Protection Law of the People's Republic of China with the responsibility to protect cultural heritage and hence some traditional villages. Since the local government did not fulfil its obligation, the procuratorate brought a PIL against it. Eventually, the court ruled in favour of the procuratorate and ordered the local government to demolish illegal constructions in the traditional villages and protect cultural heritage. However, neither the regulations nor the court judgment specifies the government departments responsible for the protection of these traditional villages and the procedure to enforce the regulation. Therefore, even upon receiving recommendations from the procuratorate, the Zaima town government did not demolish the illegal buildings in accordance with the law and did not establish a long-term protection mechanism. With the inaction of the town government, subsequently, the number of violations of the captioned regulations continued to increase. Hence, greater harm was done to the overall pattern and original features of the traditional Dong Villages. This case exposed that in the absence of detailed laws, government departments may delay in enforcing public interest-related laws even with the intervention of the procuratorate. Consequently, the public interest has suffered greater harm.

2.4. Consequences

If it takes a long time for PILs to be resolved, it may undermine public interest in at least three ways. First, one of PIL's core objectives is to rapidly stop infringing behavior and restore damaged public interests. However, prolonged litigation leads to missed governance windows, resulting in irreversible and escalating harm. This may be particularly true for environmental law cases because degradation to the environment may be hard to restore. Second, as seen, some of the causes of an inefficient PIL regime are rooted in a lack of detailed laws relating to public interest litigations. For example, in the Zaima Town cultural protection case discussed above, if the relevant law had specified which government department was responsible for enforcing the law, then the violation would not have been prolonged. Also, if the law has defined how government departments should respond to the procuratorate’s recommendation (e.g., even if not accepted, should reject with proper explanations), then public interest-related cases could be resolved faster. Even worse, protection of cultural heritage is just one example; as mentioned, there are other laws relating to public interest, but they do not provide more details to the PIL regime too. These fragmented legislations could undermine the consistency of the law as well. Third, from a broader perspective, if it takes too long to resolve PILs, it would weaken the credibility of the PIL regime. It is because the public might no longer trust the system and decide to report suspicious cases to other law enforcement agencies rather than the procuratorate. This would not only increase the cost for the procuratorate to discover violations but also prevent the PIL regime from fully performing its function.

3. Recommendations

3.1. Evidence system innovation

As discussed, PIL has long faced practical difficulties such as difficulty in obtaining cross-regional evidence and unreasonable burden of proof, which leads to the lag of damage prevention and control, and the failure of relief. In response, China should introduce a national and digital PIL evidence sharing system. Such a system consists of an electronic evidence platform that allows the procuratorate and government agencies to upload and monitor information relevant to PIL cases. The information uploaded on the centralized platform could enable the procuratorate to identify potential violations. For instance, a sudden worsening air pollution data might indicate a violation to the environmental law. To further increase the efficiency of the work of the procuratorate, the system should include an automatic warning mechanism. This means that, for example, when the data such as pollutant concentration and food and drug safety indicators are abnormal, the system automatically pushes alarm signals to the procuratorate. If this mechanism allows the procuratorate to detect violations early on, then it could even prevent a violation by warning the concerned parties early on and preventing the situation from escalating to the extent that the procuratorate must file a PIL. To the public, it means that it can suffer less or no harm. More importantly, even if the system could not identify and stop a violation early enough, the data and information stored in the centralised system could later be used as evidence in subsequent PILs. This not only dramatically reduces the procuratorate’s investigation time but might also facilitate the causality assessment process, no matter which institution conducts it.

In short, the proposed evidence sharing system is expected to enhance the overall efficiency of PIL, making it more proactive and effective in addressing potential risks and protecting the rights of the public.

3.2. Judicial system reform

Second, recall that there might be overlap in jurisdictions among different local procuratorate, leading to the shirking of responsibilities arising from vague jurisdiction provisions. In response, China should consider establishing both (1) a new division under the procuratorate that specializes in handling public interest cases that have affected multiple provinces and (2) new courts which born along with the procuratorate, specializing in handling PIL cases. For one thing, the new division under the procuratorate, instead of the local procuratorates, will be solely responsible for public interest cases that affect more than one province.

First of all, the establishment of cross-regional procuratorial departments can intervene in cross-regional public issues in advance. Realizing the treatment from the source of damage, concentrating resources such as experts, technology and funds, improving the efficiency of cross-regional evidence collection and ecological restoration. Reducing the waste of time originally caused by cross-regional justice, thus causing additional damage to public interests. Secondly, it can unify the jurisdiction and standards of case adjudication and avoid the fragmentation of legislative rules caused by different adjudication standards in many places. While ensuring that the case is handled fairly and reasonably, it will not cause the loss of judicial credibility.

Regarding the suggestion for China to establish specialized courts for PIL cases, in fact, China has established specialized courts such as intellectual property courts in the past. The establishment of specialized PIL courts will bring a number of significant advantages. First, because PIL cases are usually highly specialized and complex, covering fields such as ecological environment, food and drug safety, and consumer rights and interests protection, judges are required to have solid legal knowledge and professional knowledge and practical experience in related fields to improve the quality and efficiency of trials. Second, PIL courts specializes in handling cases related to public interest litigation, judicial staff will have relatively fixed and reasonable judgment standards after hearing similar cases. Through this standard, reasonable and effective judgments can be made faster, uneven judgments in similar cases can be avoided, judicial credibility can be enhanced, and the duration of public interest litigation procedures can be reduced.

3.3. Targeted legislation

Third, China should introduce a new law to govern PILs. As discussed, the current legal system has structural defects such as fragmentation of norms and a lack of preventive function. This calls for the country to and group these fragmented provisions into one code of the Public Interest Litigation Law. However, simply grouping the existing provisions scattered in different laws is insufficient. After introducing a PIL Law, China should continue to add details to the new statute to enhance legal clarification of the PIL regime. With a unified and detailed PIL Law, lawmakers could not only ensure that consistent rules and standards relating to PILs will be applied across the country, but also provide legal clarity to the public. By enhancing legal clarity, this would enable judicial workers to understand legal frameworks and procedures, minimizing ambiguities and disputes caused by regulatory inconsistencies. By establishing clear guidelines on case eligibility and jurisdictional authority, judicial resource allocation could be optimized, enhancing adjudication efficiency and quality to ensure timely and effective public interest protection.

In addition, to speed up the investigation of public interest cases, the new law should require suspects of a public interest case to disclose materials (e.g., data) relevant to the case to the law enforcement agency in a timely manner during the investigation. And the law should set out that suspects failing to cooperate in the investigation would be subject to a heavy fine. As such, suspects will better cooperate with the agency during the investigation and reduce the overall time needed to resolve the case. At the same time, it is also suggested to establish a follow-up evaluation mechanism for public interest damage repair through legislation to evaluate the effect of repair or compensation in time. This can prevent the increase of the second instance or the repeated prosecution of a single case due to the lawbreakers' inadequate repair or compensation.

4. Conclusion

This article reveals that the PIL system in China is facing challenges due to the difficulties in obtaining evidence, vague jurisdiction and scattered legislation. The long litigation cycle has led to further destruction in various ways and the decline of credibility. The core defects, such as high evidence cost, different jurisdiction standards and vague legislation, hinder the prevention and repair function of PIL. In light of the above, the article recommends the Chinese government to establish a national digital evidence sharing platform, establish cross-regional special PIL procuratorates and courts, and formulate a unified PIL law. Through these measures, the PIL regime could be improved such that it could resolve cases more efficiently and better protect public interests.

References

[1]. Article 55, Civic Procedure Law (2012 Revised Edition)

[2]. Decision on Authorizing the Supreme People's Procuratorate to Carry Out Public Interest Litigation Pilot Work in Some Areas

[3]. Article 55, Paragraph 2, Civic Procedure Law (2017 Revised Edition); Article 25, Paragraph 4, Administrative Procedure Law (2017 Revised Edition)

[4]. Article 25, Law on the Protection of Heroes and Martyrs (2018)

[5]. Article 106, Law on the Protection of Minors (2021)

[6]. Article 70, Law on the Protection of Personal Information (2021)

[7]. Article 47, Law on Combating Telecommunications Network Fraud (2022)

[8]. Article 63, Law on the Construction of Barrier-Free Environments (2023)

[9]. Article 99, Law on the Protection of Cultural Relics (2024)

[10]. He Xiangbai, Jia Xinyu. The Operational Dilemmas and Solutions of Environmental Administrative Public Interest Litigation with Civil Public Interest Litigation [J]. Journal of Nanjing Tech University (Social Science Edition), 2025, 24(01): 40-54+125.

[11]. Wang Bing. The Dilemmas and Solutions of Preventive Environmental Civil Public Interest Litigation [J]. Daqing Social Science, 2024, (05): 92-97.

[12]. Lin Xixi, Wang Feng. The Dilemmas and Perfection of the Preventive Environmental Civil Public Interest Litigation System [J]. Journal of Beijing University of Political Science and Law, 2024, (03): 20-25.

[13]. Wang Yifan. The Application Dilemmas and Solutions of Punitive Damages in Civil Public Interest Litigation [J/OL]. Journal of Shenyang Institute of Engineering (Social Science Edition), 2025, (01): 25-33 [2025-04-11]. [https://doi.org/10.13888/j.cnki.jsie(ss).2025.01.004](https://doi.org/10.13888/j.cnki.jsie(ss).2025.01.004)

[14]. Wang Li, Guo Ling. The Justification and Adjustment of Punitive Damages in Environmental Civil Public Interest Litigation [J]. Cross-Strait Legal Science, 2023, 25(03): 65-77.

[15]. Wu Kunrong. Research on Major Risk Identification in Preventive Environmental Civil Public Interest Litigation [D]. Southwestern University of Finance and Economics, 2023. DOI: 10.27412/d.cnki.gxncu.2023.000200.

[16]. Chen Wei. The Liability of Soil Pollution in Environmental Public Interest Litigation [D]. Jilin University, 2019.

[17]. News Peach Uptide. Some Judges Lack the Ability to Handle Complex and Difficult Cases, Leading to Extended Trial Times [https://m.thepaper.cn/newsDetail_forward_15673257](https://m.thepaper.cn/newsDetail_forward_15673257)

[18]. News Peach Uptide. The Public Interest Litigation of Chromium Slag Pollution in Qujing, Yunnan Province, Closed After Nine Years, with Luliang Chemical Company Paying 3.08 Million Yuan [https://www.thepaper.cn/newsDetail_forward_8591124](https://www.thepaper.cn/newsDetail_forward_8591124)

[19]. Li He. Where Is the Difficulty in Pricing Environmental Damage Compensation [http://www.kjw.cc/2012/06/07/31507.html](http://www.kjw.cc/2012/06/07/31507.html)

[20]. The People's Procuratorate of Huayuan County, Hunan Province, Sues the Natural Resources Bureau of Longshan County for Failure to Collect Liquidated Damages for Land Transfer [https://www.spp.gov.cn/xwfbh/dxal/202312/t20231213_636700.shtml](https://www.spp.gov.cn/xwfbh/dxal/202312/t20231213_636700.shtml)

[21]. The People's Procuratorate of Rongjiang County, Guizhou Province, Urges the Protection of Traditional Villages [https://xzyl.jsjc.gov.cn/zt/dxal/202109/t20210915_1277817.shtml](https://xzyl.jsjc.gov.cn/zt/dxal/202109/t20210915_1277817.shtml)

Cite this article

He,B. (2025). Enhancing the Efficiency of Public Interest Litigations in China. Lecture Notes in Education Psychology and Public Media,96,100-107.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceeding of ICGPSH 2025 Symposium: International Relations and Global Governance

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Article 55, Civic Procedure Law (2012 Revised Edition)

[2]. Decision on Authorizing the Supreme People's Procuratorate to Carry Out Public Interest Litigation Pilot Work in Some Areas

[3]. Article 55, Paragraph 2, Civic Procedure Law (2017 Revised Edition); Article 25, Paragraph 4, Administrative Procedure Law (2017 Revised Edition)

[4]. Article 25, Law on the Protection of Heroes and Martyrs (2018)

[5]. Article 106, Law on the Protection of Minors (2021)

[6]. Article 70, Law on the Protection of Personal Information (2021)

[7]. Article 47, Law on Combating Telecommunications Network Fraud (2022)

[8]. Article 63, Law on the Construction of Barrier-Free Environments (2023)

[9]. Article 99, Law on the Protection of Cultural Relics (2024)

[10]. He Xiangbai, Jia Xinyu. The Operational Dilemmas and Solutions of Environmental Administrative Public Interest Litigation with Civil Public Interest Litigation [J]. Journal of Nanjing Tech University (Social Science Edition), 2025, 24(01): 40-54+125.

[11]. Wang Bing. The Dilemmas and Solutions of Preventive Environmental Civil Public Interest Litigation [J]. Daqing Social Science, 2024, (05): 92-97.

[12]. Lin Xixi, Wang Feng. The Dilemmas and Perfection of the Preventive Environmental Civil Public Interest Litigation System [J]. Journal of Beijing University of Political Science and Law, 2024, (03): 20-25.

[13]. Wang Yifan. The Application Dilemmas and Solutions of Punitive Damages in Civil Public Interest Litigation [J/OL]. Journal of Shenyang Institute of Engineering (Social Science Edition), 2025, (01): 25-33 [2025-04-11]. [https://doi.org/10.13888/j.cnki.jsie(ss).2025.01.004](https://doi.org/10.13888/j.cnki.jsie(ss).2025.01.004)

[14]. Wang Li, Guo Ling. The Justification and Adjustment of Punitive Damages in Environmental Civil Public Interest Litigation [J]. Cross-Strait Legal Science, 2023, 25(03): 65-77.

[15]. Wu Kunrong. Research on Major Risk Identification in Preventive Environmental Civil Public Interest Litigation [D]. Southwestern University of Finance and Economics, 2023. DOI: 10.27412/d.cnki.gxncu.2023.000200.

[16]. Chen Wei. The Liability of Soil Pollution in Environmental Public Interest Litigation [D]. Jilin University, 2019.

[17]. News Peach Uptide. Some Judges Lack the Ability to Handle Complex and Difficult Cases, Leading to Extended Trial Times [https://m.thepaper.cn/newsDetail_forward_15673257](https://m.thepaper.cn/newsDetail_forward_15673257)

[18]. News Peach Uptide. The Public Interest Litigation of Chromium Slag Pollution in Qujing, Yunnan Province, Closed After Nine Years, with Luliang Chemical Company Paying 3.08 Million Yuan [https://www.thepaper.cn/newsDetail_forward_8591124](https://www.thepaper.cn/newsDetail_forward_8591124)

[19]. Li He. Where Is the Difficulty in Pricing Environmental Damage Compensation [http://www.kjw.cc/2012/06/07/31507.html](http://www.kjw.cc/2012/06/07/31507.html)

[20]. The People's Procuratorate of Huayuan County, Hunan Province, Sues the Natural Resources Bureau of Longshan County for Failure to Collect Liquidated Damages for Land Transfer [https://www.spp.gov.cn/xwfbh/dxal/202312/t20231213_636700.shtml](https://www.spp.gov.cn/xwfbh/dxal/202312/t20231213_636700.shtml)

[21]. The People's Procuratorate of Rongjiang County, Guizhou Province, Urges the Protection of Traditional Villages [https://xzyl.jsjc.gov.cn/zt/dxal/202109/t20210915_1277817.shtml](https://xzyl.jsjc.gov.cn/zt/dxal/202109/t20210915_1277817.shtml)