1. Introduction

The new woman is, according to Barbara Sato, a woman who transgressed social boundaries and questioned her dependence on men [1]. She started to pose a threat to the existing gender roles and even the social order during the interwar period in Japan. In general, three types of new women emerged in 20th-century Japan: the modern girls who dressed in Western style, the self-motivated middle-class housewives who were inspired by magazines, and the professional working women who developed new ideas about love and marriage. Japanese women had suffered from a long period of oppression from their family members and society, but all three types of new women began to realize that they needed more freedom and self-esteem.

The main reason for the rise of new women in Japan was Western influence. The powerful Western countries forced Japan to industrialize and accept their consumer culture and new ideas. Liberal movements happened in Japan and feminist movement was a small part of it. In the late 19th century, these movements were repressed because they opposed the Meiji government’s moderate attitude. However, another wave of feminism started when Hiratsuka Raicho established the Bluestocking Society. At the same time, Japan achieved rapid industrialization in the 19th and 20th centuries. More factories were built to produce goods that responded to the growing demand of society; department stores opened in urban city areas; and women's magazines introduced these consumer goods to women. An increasing number of women went shopping to escape from their stressful domestic work. These conditions laid the groundwork for the awakening of new women.

On the other hand, Japanese women also learned about feminist ideas and the feminist movement taking place in Europe and America. People who travelled to other countries brought back their modern ideas and tried to persuade Japanese women that they could be respected and have their own lives as well. They wrote in magazines and spread their influence little by little.

2. Modern girls

Modern girls represented the import of consumer culture in Japan because they were largely affected by the figures of girls in American movies. They started to dress in a Western style and imitated how American girls acted in the movies. These young and modern girls were chosen to advertise department stores. For example, the famous cosmetic company Shiseido used them to demonstrate its latest beauty products. When they first appeared, they seemed like another change in fashion and hairstyle, which was not favorable in the eyes of most Japanese people. In the past, women kept long hair and wore traditional kimonos and geta. Kimonos were beautiful and represented Japanese culture, but women were restricted because they could not move conveniently, and they often stayed at home. However, modern girls cut their hair and wore short dresses and high heels, as seen in Figure 1. This change from wearing clothes that limited girls’ movement to clothes that were prettier and more convenient showed that these girls were breaking free of their traditional boundaries.

Modern girls were in fact only a small portion of the population, but the reason they attracted so much attention was that they represented what all women could become. Modern girls would not be called “modern” if they only dressed modernly, they spoke for themselves instead of being humble and always listening to other people’s opinions. Some of them chose to oppose societal criticism of them and do what they wanted to do.

Modern girls received opposition from society and even their own families. Intellectuals claimed that they were hedonistic and were a bad influence on society. People thought they were girls who didn’t listen to elder people’s words and messed around with bad boys. In most rural areas, people related them to sexual figures, so these girls were hated by their closest people. Under these circumstances, there were still many girls who had the courage to make their own decisions. A young novelist named Mochizuki Yuriko cut her hair after she came back from Europe. People hissed at her when she was walking on the street, and her mother said she had embarrassed the family and wanted her to return to where she worked. In this case, Mochizuki responded by ignoring the outside voices and following her own decision. On one occasion, an elderly woman on the train said to Mochizuki, “You are so young, and you had to cut off your hair. When did you lose your husband?" [2]. In the past, women cut their hair when their husbands died to demonstrate their devotion and intention not to marry again, while now women cut their hair not for other people but for their own preference. This was the attitude that modern girls tried to show: women could decide what they wanted for themselves.

3. Self-motivated middle-class housewives

The rise of modern girls, middle-class women, and professional working women all resulted from the development of magazines. Among all of them, self-motivated middle-class women were probably most affected by magazines. Therefore, it is important to discuss how magazines started to impose such a large influence on women. One reason that the magazines were more successful in Japan than in other countries was that nearly all Japanese women had to take care of their families, so they purchased magazines that told them how to do so. Magazines that targeted women were often written by well-educated women (compared to other women, not to men). At first, only women with higher education subscribed to magazines because only they had the ability to purchase them. When literacy rate increased, more women started to purchase magazines, and people could see them reading a magazine on the train, on the street, or at home. Magazines aimed “to supplement those areas that are lacking in women’s education today... cover all facets of knowledge that a woman needs in order to become enlightened and knowledgeable in the necessary techniques required for understanding her household work... hope to help form wise mothers and good wives.” [3]. However, as magazines grew with the growing population of educated and economically independent women, they not only taught living techniques and told interesting stories, but also started to teach women how to live their own lives.

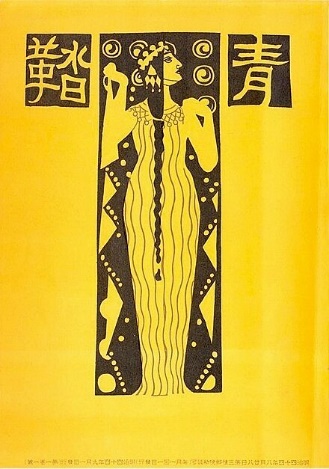

Many feminists in Japan were magazine editors. They shared their ideas and enlightened their readers. Figure 2 shows the magazine of Seito, which was created by a group of women led by Hiratsuka Raicho. She wrote, “When I looked at the women around me, they seemed false. They were presumably endowed with extremely admirable qualities, but these remained hidden because of social conditions. They were surely capable of greater things, but their innate strengths were kept in check. The time had come for them to throw off the dead weight of oppression, assert their true selves, give full expression to their individual talents, and articulate their thoughts boldly and honestly. Then, and only then, would they truly be women.” [4]. She claimed that women had great qualities and could achieve great things, but they were limited by social boundaries. It was time for them to show their true ability and be themselves. Yosano Akiko was a famous poet and writer, and she wrote, “I don’t want to draw sharp distinctions between men and women and to boast that women are superior beings. Women are only human. I would like to see men and women carry on their lives cooperatively, choosing work to which each is best suited, and giving up their biased ideas, such as that childbirth is disgusting, while war is noble.” [5] She hoped to see cooperation between men and women and that people would give up their biased ideas based on gender. Ito Noe spoke against an arranged marriage and wrote, “The agreement was made in circumstances in no way different from those common in most such cases: based on the needs of my parents, and to me essentially a humiliation. Of course, I was unable to be submissive as was the wish of my parents. I fled, more or less blindly and straight ahead, out of the boundaries set by a situation that baffled and dumbfounded me. Because of that, my parents and everyone else concerned lost their standing with others. The man selected as my partner and his parents also lost face. I exposed myself to all the malice and resentment and grief of those people, and to the scorn and abuse of the numerous defenders of convention. What really led me to the depths of despair was the surprisingly powerful pain of seeing the grief of my family. But the small thing that sustained me was a belief in the truth that was clearly warning me not to trust the customs that threatened to break me. And what was stronger than the power of the logic of that belief was my passion for love. Any suffering, any sadness, was comforted and healed by love. This strengthened my aversion to ‘forced marriage.’” [6]. She used her own example to tell women not to be restricted by social norms. These famous feminists wrote in magazines to address certain issues and change women’s ideas. They arranged meetings with other editors to discuss these issues in the hope that women would not be threatened by other things and could just be themselves.

There were several types of articles that a magazine could contain: practical articles, trendy articles, gossip columns, and confessional articles. While in the past, mothers imparted their daughters knowledge about domestic lives; practical articles now provide this information. Women learned how to manage financial costs, how to prevent health issues, and how to cook certain dishes. Trendy articles informed the latest fashion styles, hairstyles, and dance steps. Better quality of photographs helped trendy articles present their contents better, but in general, these articles were written to attract readers to buy magazines instead of addressing any specific issues about women’s situation.

The most important articles were probably gossip columns and confession articles. Young women were concerned about finding a decent mate and their lives after marriage, and gossip columns gave them more courage to make choices themselves. These columns wrote about love stories of famous people, including famous women, so female readers could realize that there was already someone who refused to follow traditional marriage patterns. One famous example was the story of Yoshikawa Kamako. She was married to a wealthy businessman but tried to commit suicide with her chauffeur. The chauffeur died, but Kamako survived and was accused by society. [7]. People noticed that even though she was the one who betrayed her husband, her husband failed to fulfil his role as a husband and made her wife search for comfort from a chauffeur instead of him after their marriage. They started to question the role of a husband in a family. On the other hand, Kamako didn’t consider how she could be seen by other people, and she decided to do things based on her instinct. Female readers felt sympathetic for her situation and saw her courage to pursue her own happiness.

Confessional articles were written by readers rather than the magazine editors. At the beginning, magazines asked their readers to send them questions, and editors could answer the questions and post them on magazines. This allowed the development of a closer relationship between the readers and the editors and thus increased the selling of magazines. Then readers started to write about their own stories and sent them to magazines. By reading confessional articles, middle-class housewives found that most of them shared a comparable situation: they were married to someone that they did not like, lived with their husband’s families, and experienced depressing lives. Hence, a reader could easily relate herself to confessional articles written by another sad woman and feel sympathetic for both the woman and her. Women realized that they were not alone, and they formed a special bond with other readers.

The government of Japan began to worry about the influence of magazines, claiming that they tried to tell women to break free of the “good wife, wise mother” ideology. The February issue of Seitō and the May issue of Jogaku sekai were both banned from sales racks, but women still found reading an important part of their lives. By adopting confessional articles, magazines became a forum. The confessional articles written by many kinds of women showed that some of them were becoming more and more independent, and their lives gave other readers an idea about how their lives could become.

4. Professional working women

Professional working women started to appear in society during wartime. While in the past, a woman dedicated her entire life to serving her family and her husband’s family without leaving the domestic sphere, now she has the opportunity to be in society and experience things on her own. Women began to be a part of the male-dominant workforce and faced several challenges. They entered the workplace for mainly two reasons: economic support for their families and the will to self-cultivate.

Some women wanted to alleviate the economic burden of their families by supporting themselves, and others wanted economic independence. However, this was very hard to achieve. Women employed generally had a higher education background and work opportunities were limited. They received little wages. Women in rural areas had to go to cities to find jobs, which often resulted in harsh jobs in factories.

Another big reason for women to become a part of the workforce was the desire to self-cultivation, which was to develop skills and be prepared for later marriage. Although intellectuals criticized that women were not focusing on the domestic sphere anymore, which was intolerable according to the tradition in Japan, working in society was believed to be beneficial for those women. After marriage, women needed to acquire knowledge to perform basic tasks at home, such as cooking and sewing. They also needed to have good manners. However, to take care of the family well enough, women had to have enough social experience and skills, which they could not learn simply from attending high schools or reading magazines. Therefore, being in society before marriage was thought necessary. Women also believed that if they held a job before getting married, they could have more economic power and experience to deal with things, which improved their status in their husbands’ families.

One notable woman is Hani Motoko, a journalist and an important figure in promoting women’s education. Her successful marriage helped her crystallize her idea that an ideal family required the unification of the husband and the wife. Husbands needed their wives’ support, and wives needed their husbands’ support. Without mutual support from both sides, “wife would eventually become a servant to her husband. This has been the case in the past, not only in Japan but also in the West. We have gradually become aware of She focused on making women a more helpful figure in marriage.” [8]. Even though she reinforced the traditional women’s role in the family, she expected women to have more individuality and self-esteem. She did not like the values taught in most Japanese schools for women, which stressed conformity and obedience. Rather, she wanted girls to know how to be a helpful figure in her family. Therefore, Motoko and her husband worked together and created a school named Jiyu. “Jiyu” means freedom in Japanese, and the name of the school represented her wish that women could enjoy more freedom by getting well-educated. Her ideas influenced and represented most young women’s ideas towards self-cultivation before marriage.

However, this pursuit of self-cultivation was not beneficial for women in rural areas. Apparently, they did not consider working in the countryside to cultivate themselves. After reading the magazines, they imagined dressing nicely and working in cities, and many young women streamed into cities to gain a job. The Tokyo Asahi reported that “As might be expected, of the 819 cases that were handled, the most common problem concerned finding suitable employment: 280 women raised that issue. Among the coveted jobs, department store sales and office work ranked highest on the list. In most instances, young women said reading about these things in women’s magazines brought them to Tokyo.” [9]. The mindless trust in magazine articles caused the unemployment of women from rural areas.

In addition, female workers were bound by their sex. Only a few women could receive the intellectual work that most men did. Companies recruited women for their appearance because they could be sent out to attract male customers and facilitate difficult transactions. Young women usually got jobs like mannequin girls, who worked as fashion models; taxi girls, who looked pretty and accompanied taxi drivers; and usherettes, who led people to their seats in a movie theatre. Just like the mannequin girl in Figure 3 shows, those jobs did not require women to use the knowledge they got from schools but used their appearance and the general knowledge that pretty faces attract male customers. Women’s potential was greatly undermined because no one was willing to see what they could do and listen to their thoughts.

Working outside of the home not only meant that women were gaining social experiences but also had a new kind of view that emphasized the spiritual bond between wives and husbands, and this was considered self-cultivation for these women as well. While in the past, marriage was arranged by parents and was based on the consideration of financial aid that the husband’s family could provide, now working women claimed that marriage should be based on love between a couple. Marriage was not uncommon, but the selection of the husband was pivotal because it determined the quality of the rest of a girl’s life. People also recognized the importance of love in a marriage. In an issue of Fujin Koron, a jurist said, “Marriage in the true sense of the words means that a man and a woman must love each other and become one mentally and physically. They had to help each other, continue to be diligent in their practice of self-cultivation and contribute to the development of world civilization.” [10]. As a result of experiencing in society as a working woman, girls felt that it became more difficult to choose a mate because they had higher standards or simply because they realized they did not like how men behaved after marriage for hundreds and thousands of years. Many men visited geisha and pleasure quarters even after they were married. Women now felt that it was not fair for them to keep their virginity, while men had the right to visit those places and have affairs with other women, both before and after marriage. Ito Noe’s opinion explained this. In her mind, marriage was an economic arrangement, but a woman had to pay her name and her entire life. A man also had to pay economically for this arrangement, but he was not limited by marriage more than a woman was. Now that women realized that they were treated unfairly, they wanted to reject this. Some women were considering more than this problem: they tried to gain equal rights and wanted to marry a man who would only love her and marry her for herself, not for her family’s economic conditions and titles.

Even though women’s goal was not to disappoint their families, their actions were criticized. Women’s parents did not take their emotions and feelings into account when choosing husbands but forced them to pay back the money spent on them. If a girl did not listen to her parents, chose a man on her own, and failed to have a happy marriage because of any reason, her parents would accuse her of being hubristic. However, the courage to disobey the traditional expectations showed that these young girls were willing to bear the responsibility of their own choices rather than simply subordinating to their parents’ decisions and taking the consequences of those decisions.

5. Conclusion

In conclusion, all three figures of new women questioned the existing social order and their dependence on men. Modern girls decide their appearance, middle-class housewives read about the possibility that they could become, and professional working women develop themselves by going out to work and having a new idea about love and marriage. Even though there were three categories of new women, that did not mean that a new woman could only be categorized as one type. For example, Hani Motoko was a working woman and a housewife. She worked as a magazine author, and she was a wife and a mother. As a writer, she told her female readers not to be slaves of their husbands but to work together to make their marriage successful. As a housewife, she believed in the power of love and worked hard to maintain a good relationship with her husband and build up a harmonious family for herself.

All types of new women received a large amount of accusation from both the society and their close people. Those critics targeted new women because they were breaking free of the old expectations of them. Modern girls seemed like a product of hedonistic consumerism and were criticized for their new appearances. They refused to wear the traditional clothing that restricted their development and pursued a new fashion style. Self-motivated middle-class women and magazines were criticized because independent women’s stories motivated women who still dedicated their lives to their families. They started to ask for more freedom and became less submissive. Finally, professional working women were criticized and sometimes punished because they wanted to choose their own husbands. They were also restricted to jobs that only required them to be pretty figures. Some women were affected by different opinions from society, but many decided to be responsible for themselves and ignored the outside voices.

In Hiratsuka Raicho’s words, “In short, I was saying that each and every one of us was a genius.” [11]. In a society that expected women to only take care of the family and ignored the needs of the women themselves, it was valuable to recognize that every woman had the potential to do things besides housework. They had their deep thoughts, their interests, and ability to work outside of domestic spheres. Women needed to fulfil their needs and desires, and becoming one of the new women was the first step. Even though women had little freedom until the mid-20th century, they were granted the right to vote; in the early 20th century, their actions were a big step towards gaining women more rights in Japan.

References

[1]. Barbara Sato. The New Japanese Woman, pp. 13. Duke University Press (2003).

[2]. Mochizuki Yuriko. ‘‘Shindanpatsu monogatari’’ (Josei, March 1928), in Dokyumento Shōwa sesōshi senzen hen (Tokyo: Heibonsha, 1975), pp. 122–23.

[3]. “Jogaku sekai, ” January 1901, pp. 1–3.

[4]. Hiratsuka, Raicho. In the Beginning, Woman was the Sun: The Autobiography of a Japanese Feminist. Translated by Teruko Craig. pp. 144.

[5]. Akiko, Yosano. Ubuya monogatari (XIV: 3).

[6]. Itõ, Noe. Teihon Itõ Noe zenshu. Pp. 436.

[7]. Abe, Jirō. “Untenshu to hakushaku fujin no ai, ” in Rekishi to jinbutsu (Tokyo: Chūō kōronsha, April 1980), pp. 110–15.

[8]. Hani, Keiko. comp. Hani Motoko ikkan senshu (Tokyo, 1970). Pp 83-89.

[9]. Tokyo Asahi shinbun, June 19, 1932.

[10]. Yamawaki Gen, “Musume chūshin no jiyū kekkon nare, ” Fujin kōron, July 1919. Pp. 30.

[11]. Raicho, Hiratsuka. In the Beginning, Woman was the Sun: The Autobiography of a Japanese Feminist. Translated by Teruko Craig. Pp. 144.

Cite this article

Huang,Y. (2025). The New Woman in 20th-Century Japan. Lecture Notes in Education Psychology and Public Media,108,85-92.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Global Politics and Socio-Humanities

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Barbara Sato. The New Japanese Woman, pp. 13. Duke University Press (2003).

[2]. Mochizuki Yuriko. ‘‘Shindanpatsu monogatari’’ (Josei, March 1928), in Dokyumento Shōwa sesōshi senzen hen (Tokyo: Heibonsha, 1975), pp. 122–23.

[3]. “Jogaku sekai, ” January 1901, pp. 1–3.

[4]. Hiratsuka, Raicho. In the Beginning, Woman was the Sun: The Autobiography of a Japanese Feminist. Translated by Teruko Craig. pp. 144.

[5]. Akiko, Yosano. Ubuya monogatari (XIV: 3).

[6]. Itõ, Noe. Teihon Itõ Noe zenshu. Pp. 436.

[7]. Abe, Jirō. “Untenshu to hakushaku fujin no ai, ” in Rekishi to jinbutsu (Tokyo: Chūō kōronsha, April 1980), pp. 110–15.

[8]. Hani, Keiko. comp. Hani Motoko ikkan senshu (Tokyo, 1970). Pp 83-89.

[9]. Tokyo Asahi shinbun, June 19, 1932.

[10]. Yamawaki Gen, “Musume chūshin no jiyū kekkon nare, ” Fujin kōron, July 1919. Pp. 30.

[11]. Raicho, Hiratsuka. In the Beginning, Woman was the Sun: The Autobiography of a Japanese Feminist. Translated by Teruko Craig. Pp. 144.