1. Introduction

1.1. Social background

Stay-at-home Dads (SAHDs) used to be considered a non-traditional and underrepresented gender role in China. However, after the unprecedented COVID-19 pandemic, more and more fathers, by choice or by necessity, become stay-at-home dads who hold no full-time jobs but take primary responsibility for raising children. A recent survey, conducted by The Social Survey Center of China Youth Daily associated with Wenjuan.com, further verifies this trend. Among 1,987 married young Chinese participants, the proportion of men who support their husbands becoming Stay-at-home Dads (52.4%) is higher than that of women (45.8%) [1]. However, few study contributes to a growing body of literature exploring the psychological well-being of stay-at-home fathers. It is important because those male individuals are a group that has received relatively less attention in psychological research, particularly in Chinese culture where their role is less conventional. As traditional gender roles continue to evolve, understanding the emotional and psychological impacts of family role reversals is crucial for both relationship counseling and gender studies. Among these, levels of self-esteem have consistently been found to predict success and well-being across various life domains, including relationships, work, and health, with these benefits being evident across all ages, genders, and racial/ethnic groups[2].

This research aims to evaluate whether rejection behaviors from a romantic partner, have an impact on the level of stay-at-home dads’ self-esteem (i.e., being rejected when asking for help). We tested the change of stay-at-home dads’ self-esteem under a specific help-rejection scenario. Specifically, we predicted that being rejected by a romantic partner might be able to diminish the level of self-esteem for stay-at-home dads in China, which might be an implicit damage to their relationship satisfaction.

1.2. The importance of self-esteem

Self-esteem affects the occurrence of significant transitions within the relationship domain, which, in turn, influence the further development of self-esteem[3]. Individuals with low self-esteem often exhibit sensitivity and self-doubt in intimate relationships, actively avoiding behaviors they perceive as revealing their vulnerabilities. People with low self-esteem significantly underestimate their partners’ positive views of them. This unnecessary and unwanted insecurity is associated with less generous perspectives of their partners and lower relationship happiness[4]. Self-esteem is an important link between social recognition, interpersonal characteristics, interpersonal behavior, relationship quality, and relationship stability[5]. It is believed that self-esteem is closely linked to self-esteem support. Higher self-esteem will predict higher efficacy and self-esteem support when a partner needs support[6].

1.3. Challenges to SAHDs’s self-esteem

In traditional Chinese families, the division of labor has typically followed the model of "men working outside and women staying at home." As a result, society holds considerable prejudice against men who are not the primary breadwinners, often marginalizing stay-at-home fathers[7]. Unlike women, whose sense of security are more closely tied to self-perception, men’s security is often tied to their perceived ability and contribution, particularly in terms of financial support[8]. When fathers transition from financial providers to stay-at-home roles, they may experience feelings of inadequacy or judgment, as societal expectations dictate that men should be the primary financial contributors. This shift in gender roles can induce feelings of insecurity and inferiority.

Previous research has emphasized the importance of relationship experiences in shaping personal self-cognition[9]. People's emotional tendencies, such as experiencing positive or negative affect, influence their perceptions of personal strengths and weaknesses and, as a result, affect their self-esteem[10]. In intimate relationships, individuals with high self-esteem are generally less sensitive to rejection[11]. Conversely, individuals with low self-esteem tend to seek indirect support to shield themselves from potential exclusion. Ironically, this can provoke negative responses from their partners, thereby undermining the acceptance and validation that low self-esteem individuals crave[12].

For stay-at-home dads, a perceived imbalance in decision-making power can further amplify feelings of rejection and undervaluation, potentially leading to frustration. Therefore, stay-at-home dads must receive both behavioral and emotional support from their spouses, as this support plays a key role in marital satisfaction and personal fulfillment[13].

1.4. Present work

This mixed-methods research across two phases (1 - an experiment, 2 - a survey) examines the impact of a partner’s refusal to help on the self-esteem of stay-at-home dads in urban China. Phase 1, an experimental study, will measure whether SAHDs experience changes in self-esteem when their requests for help from their wives are either accepted or rejected. We will involve the same number of non-SAHDs to do the exact experiment as SAHDs to examine whether these results are role-specific. Thus, we will have four controlled groups: SAHDs in the Rejection Group, SAHDs in the Acceptance Group, non-SAHDs in the Rejection Group, and non-SAHDs in the Acceptance Group. We will compare the four control groups pairwise for t-test analysis.

Phase 2, a survey study, will collect the family income data of all SAHDs participants in Phase 1 and use linear multiple regression analysis to test if family income is a potential moderating variable affecting the result with-in SAHDs.

The studies are conducted in cities in Southern China (e.g., Shanghai, Shenzhen, and Hangzhou) to focus on economically developed areas with similar understanding and practices of family roles.

2. Study (phase 1)

2.1. Method

All measures, manipulations, and exclusions will be comprehensively reported. This study will receive approval from the Institutional Review Board for human participants and will be conducted following its guidelines. Written informed consent will be obtained from each participant prior to their involvement in the study.

Participants. 256 couples will be recruited to participate in exchange for The Impact of Partner’s Refusal to Help on the Self-Esteem of stay-at-Home Dads. Among those, 128 are SAHDs and their wives, 128 are non-SAHDs and their wives. The inclusion criteria for the SAHDs group will be that dad individuals are primary caregivers, not engaged in full-time employment outside the home, and have at least one child living with them. Non-SAHDs must work full-time outside the home. Participants will be excluded if they fail to take attention check. We hope to recruit 512 total participants (256 males and 256 females).

Our primary hypothesis is SAHDs will experience fluctuation in the level of self-esteem when their request for help is rejected by their wives and lead to a greater decline in self-esteem compared to non-SAHDs. Our secondary hypothesis is SAHDs stability of self-esteem show clear association with family income. SAHDs with higher family incomes have more stable emotions and experience less self-esteem damage when facing rejection from their wives than those with lower family incomes.

For Phase 1, we performed a power analysis using the software package G*Power[14]. For either randomly assigned group(dad type or help respond), the results indicated that with N=128, our experiment could detect an effect size of Cohen’s d of .25, using t-tests at a 5% alpha level threshold with 80% statistical power.

2.2. Study design

Procedures. The study included 512 participating couples, divided equally into four groups (SAHDs accepted/rejected, non-SAHDs accepted/rejected), with 64 couples in each group. Participants completed a series of questionnaires, including measures described below. Fathers were randomly assigned to one of two conditions: help-refusal or help-acceptance from their partner. Each group was further divided into these two conditions, resulting in four distinct groups. In each condition, fathers were instructed to ask their wives for assistance with a specific task (e.g., "Can you help me prepare dinner tonight?" or "Can you help me take the kids camping this weekend?"). Wives were briefed beforehand about their assigned condition and instructed to either refuse or accept the request. In the two rejection groups, wives refused the request, while in the two acceptance groups, they complied. Five minutes after the interaction, fathers were asked to complete the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSES) to measure changes in the level of self-esteem from pre- to post-experiment.

2.3. Measures

The Level of Self-esteem. 10 items of The Rosenberg Self-esteem Scale(RSES) are utilized to assess the level of male participants’ self-esteem. Scoring integrates a combination of item ratings. Responses indicative of low self-esteem include “disagree” or “strongly disagree” on items 1, 3, 4, 7, and 10, and “strongly agree” or “agree” on items 2, 5, 6, 8, and 9. Items are scored based on specific combinations: for items 3, 7, and 9, a response is scored if two or three out of three answers are correct; for items 4 and 5, one or two correct answers out of two are counted as a single score; Individual scores are assigned to items 1, 8, and 10, while items 2 and 6 are scored as a single item when one or two out of two answers are correct [15].

Relationship Satisfaction. 5 items from the Investment Model Scale(IMS)[16] are utilized to measure relationship in satisfaction level(e.g., “Our relationship makes me very happy”; α = .87). The items are measured on a 9-point scale (1 = strongly disagree to 9 = strongly agree).

Relationship Commitment. 7 items from the Investment Model Scale(IMS)[16] are applied to evaluate relationship in commitment level(e.g., “I am committed to maintaining my relationship with my partner”; α = .87). These items are also measured on a 9-point scale (1 = strongly dis-agree to 9 = strongly agree).

2.4. Data analytic approach

A series of t-tests with only one variable controlled (dad type or help response) will be used to analyze the effects of the specific independent variables on self-esteem change. First, the experimental data is analyzed to compare the changes in dads participants' self-esteem under the conditions of refusing help and accepting help. Then, the experimental data also examine whether there is a significant difference in the change in self-esteem levels of SAHDs and Non-SAHDs when confront rejection from their wives.

2.5. Results

Descriptive statistics.

The hypothetical results based on a change in self-esteem scores (measured before and after the help-seeking scenario) and conduct independent samples t-tests for pairwise comparisons between the groups. We predict that self-esteem decreases more when help is rejected, and SAHDs are more sensitive to rejection than non- SAHDs.

Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSES) scores are measured on a scale from 10 to 30. Most individuals score between 15 and 25. A score below 15 may indicate potential concerns with low self-esteem.

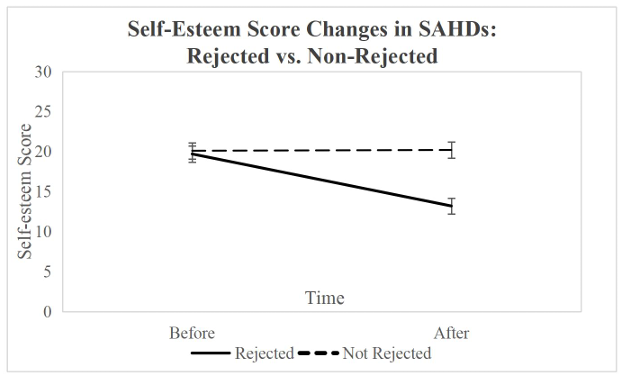

Aim 1. Examine changes of Self-Esteem score in SAHDs under two different situations. See Figure 1.

Estimated marginal means for self-esteem scores in stay-at-home dads (SAHDs) who were rejected and not rejected while childcaring, measured before and after the rejection event. The solid line represents SAHDs who were rejected, and the dashed line represents those who were not rejected. Error bars represent ±1 Self-esteem above and below the mean. Greater self-esteem is indicated by higher numbers. The figure shows a decrease in self-esteem for rejected SAHDs, while self-esteem for non-rejected SAHDs remains relatively stable across time. It can be confidently stated that the rejection event significantly impacts self-esteem for SAHDs, and this effect is unlikely to be explained by random variability in the data. (p < .05)

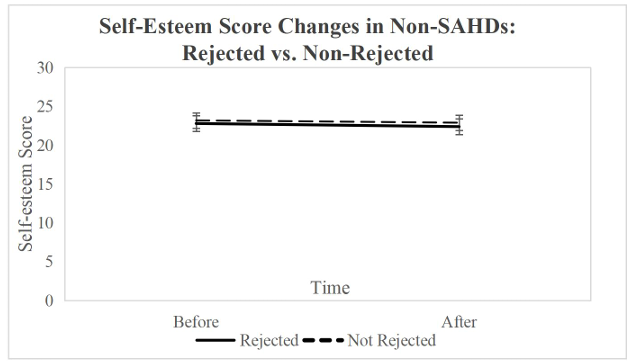

Aim 2. Examine changes of Self-Esteem score in non-SAHDs when confronting help-refusal situation. See Figure 2.

Estimated marginal means for self-esteem scores in non-stay-at-home dads (non-SAHDs) who were rejected and not rejected while childcaring, measured before and after the rejection event. The solid line represents non-SAHDs who were rejected, and the dashed line represents those who were not rejected. ±1 Self-esteem above and below the mean is represented by error bars. Better self-esteem is indicated by higher self-esteem scores. The results showed no significant interaction between rejection condition and self-esteem scores in non-SAHDs, suggesting that rejection did not significantly impact self-esteem scores in non-SAHDs (p > .05).

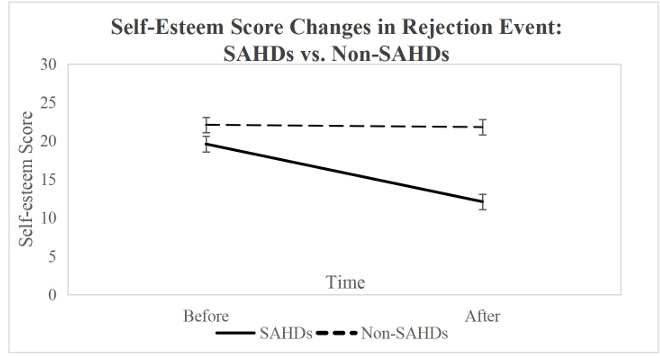

Aim 3. Compare changes of Self-Esteem score in rejection event between SAHDs and non-SAHDs. See Figure 3.

Estimated marginal means for self-esteem scores in stay-at-home dads (SAHDs) and non-stay-at-home dads (non-SAHDs) before and after the rejection event while childcaring. The solid line represents SAHDs, and the dashed line represents non-SAHDs. Error bars indicates ±1 Self-esteem above and below the mean. Higher self-esteem scores indicate better self-esteem. A significant interaction was observed between the rejection event and the self-esteem score of non-SAHDs, with SAHDs experiencing a significant decline in self-esteem after the rejection event (p < .05). While non-SAHDs showed little to no change in self-esteem across time.

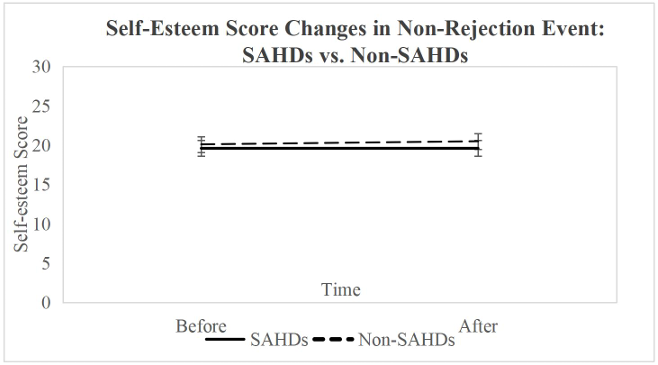

Aim 4. Compare changes of Self-Esteem score in non-rejection event between SAHDs and non-SAHDs. See Figure 4.

Estimated marginal means for self-esteem scores in stay-at-home dads (SAHDs) and non-stay-at-home dads (non-SAHDs) before and after the non-rejection event while childcaring. The solid line represents SAHDs, and the dashed line represents non-SAHDs. Higher self-esteem scores represents better self-esteem. There was no significant interaction between time and group, suggesting that both SAHDs and non-SAHDs maintained relatively stable self-esteem scores across time (p > .05).

The predictive results indicate that help-rejection has a significant impact on self-esteem, particularly for SAHDs. Rejection affects SAHDs more than non-SAHDs, and even when help is accepted, SAHDs still show a small decline in self-esteem compared to non-SAHDs. This suggests that both the help-seeking response and the role of being a SAHD are important factors influencing self-esteem.

3. Study (phase 2)

Participants. 128 SAHDs in Study 1 will be recruited to participate in investigating if family income moderates the effect of help-seeking rejection on self-esteem. Participants will be excluded if they fail to take an attention check.

Based on theoretical assumptions, our primary hypothesis is family income will moderate the effect of help-seeking rejection on self-esteem. Specifically, SAHDs with lower family income may experience greater declines in self-esteem when their help-seeking requests are rejected, compared to those with higher family income. Our secondary hypothesis is for those whose requests for help are accepted, the effect of family income on self-esteem may be minimal, as the positive outcome (i.e., receiving help) buffers any potential financial stress effects.

For Phase 2, we conducted a power analysis using G*Power[14]. Since we will have all 128 SAHD participants fill out the survey, the results suggested that with N=128, our experiment could identify an effect size of Cohen’s d of .15, employing f-test at a 5% alpha level threshold with 95% statistical power.

3.1. Study design

Procedures. Having all SAHD participants report their family income by filling out a marital status questionnaire. The number of income data of SAHD participants who were randomly assigned into the help-rejection group in Study 1 should be collected as a continuous variable (e.g., annual family income in Chinese Yuan) during the survey process. The primary dependent variable is the fluctuation in self-esteem scores from the pre-test to the post-test (after the help-seeking experiment). Gather these data and conduct a Linear Regression Analysis.

3.2. Measures

Marital Status. A survey consists of 10 items on marital status is used to collect basic family information of the participants (e.g., “How long have you been married”, “How many children do you have”, “Who is the primary child caregiver in your family”). Questions about annual family income are also included in the survey (A number of annual family income in Chinese Yuan before tax, e.g., 50 thousand Chinese Yuan per year).

3.3. Data analytic approach

We use Linear Regression Model Equation to check if the effect of help-refusal on self-esteem is stronger for dad participants with lower family income than for those dads with higher family income. Here’s the equation:

Change in Self-Esteem=a(Family Income)+b

We use excel to run the analysis.

3.4. Results

Descriptive statistics.

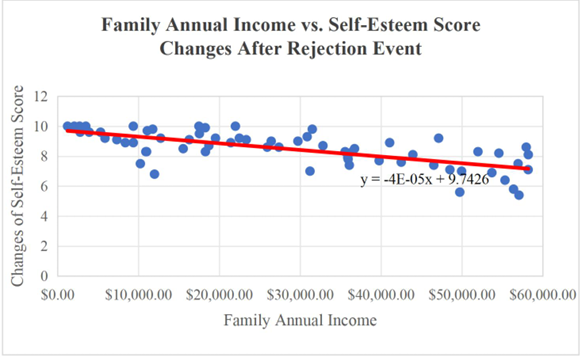

Aim 5. Demonstrate whether Family Annual Income is a moderating variable in changes of Self-Esteem level. See Figure 5.

The scatterplot illustrates the relationship between family annual income (ranging from $0 to $60,000) and changes in self-esteem scores in fathers following a rejection event while caring for children. The blue dots represent individual data points, and the red line indicates the linear regression trend, showing a slight decrease in self-esteem score as family income increases. The equation for the regression line is provided in the figure: y=−4E−05x+9.7426, suggesting that higher income is linked to a less pronounced decline in self-esteem score. We collected data from 64 participants, all fathers (SD = 3.2). SD=3.2 means on average, the fathers’ changes in self-esteem score deviate from the mean by approximately 3.2. In general, about 68% of the participants' ages would lie within one standard deviation assuming a normal distribution.

4. Conclusion

This study aims to explore whether seeking help but being rejected is an important regulating factor in the damage to the self-esteem of stay-at-home dads in their feedback on interactions with their partners. The study also seeks to explore whether specific moderating variables, such as family income levels, influence the extent of self-esteem fluctuations in both groups when their requests for assistance are accepted or rejected by their partners, enhancing the understanding of how socio-economic factors influence self-esteem outcomes in help-seeking scenarios. This study attempts to clarify whether the self-esteem level of Chinese male individual is affected by partner interaction when facing the emerging family role of becoming a stay-at-home dad through quantitative research methods.

This study focuses on a specific, under-researched population—stay-at-home dads. By using a control group of non-stay-at-home dads, the study can offer insights into how role dynamics influence self-esteem in different family structures. The incorporation of real-life help-seeking scenarios adds ecological validity to the experiment, allowing the results to reflect everyday challenges faced by these fathers.

One limitation of this study is the relatively small sample size (N=64 per group). It may not have enough power to detect statistically significant differences, enhancing the reliability of the findings. Meanwhile, the reliance on self-reported measures of self-esteem, can be subject to social desirability bias. Participants may be inclined to report higher self-esteem levels than they truly feel, especially in the context of their family roles.

Our next step is to investigate into long-term effects of help-seeking rejection on stay-at-home dads’ self-esteem. Longitudinal studies can provide a more comprehensive view of how these interactions affect individuals over time. Furthermore, future work will explore how other moderating variables, such as education level, number of children, or length of marriage, regulating the level of stay-at-home dads’ self-esteem under this circumstance. For couples with stay-at-home dads, a deepened understanding of this dynamic can help them improve their communication strategies and navigate healthier emotional responsiveness. Our research will shed light on how therapy can intervene to adjust both parties’ expectations and improve long-term relationships with a stay-at-home dad in the house.

References

[1]. Yuanchun, Du, & Lingwen, Gu, (2019, August 22). Becoming Stay-at-home Dads: Higher Acceptance by Male Interviewees than Female. www.Cyol.com. https: //zqb.cyol.com/html/2019-08/22/nw.D110000zgqnb_20190822_1-08.htm

[2]. Orth, U., & Robins, R. W. (2022). Is high self-esteem beneficial? Revisiting a classic question. American psychologist, 77(1), 5.

[3]. Luciano, E. C., & Orth, U. (2017). Transitions in romantic relationships and development of self-esteem. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 112, 307-328.

[4]. Murray, S. L., Holmes, J. G., & Griffin, D. W. (2000). Self-esteem and the quest for felt security: how perceived regard regulates attachment processes. Journal of personality and social psychology, 78(3), 478.

[5]. Jessica J., C., & Steve, G. (2018) Does Self-Esteem Have an Interpersonal Imprint Beyond Self-Reports? A Meta-Analysis of Self-Esteem and Objective Interpersonal Indicators, Personality and social psychology review : an official journal of the Society for Personality and Social Psychology, Inc, 23.1: 73-102.

[6]. Jayamaha, S. D., & Overall, N. C. (2019). The dyadic nature of self-evaluations: Self-esteem and efficacy shape and are shaped by support processes in relationships. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 10(2), 244-256.

[7]. Huang, F. (2023). Stay-at-home Fathers in Contemporary Urban China (Doctoral dissertation, University of Westminster).

[8]. Brennan, K. A., & Morris, K. A. (1997). Attachment styles, self-esteem, and patterns of seeking feedback from romantic partners. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 23(1), 23-31.

[9]. Auger, E., Thai, S., Birnie-Porter, C., & Lydon, J. E. (2024). On Creating Deeper Relationship Bonds: Felt Understanding Enhances Relationship Identification. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 01461672241233419.

[10]. Pelham, B. W., & Swann, W. B. (1989). From self-conceptions to self-worth: on the sources and structure of global self-esteem. Journal of personality and social psychology, 57(4), 672.

[11]. Murray, S. L., Rose, P., Bellavia, G. M., Holmes, J. G., & Kusche, A. G. (2002). When rejection stings: how self-esteem constrains relationship-enhancement processes. Journal of personality and social psychology, 83(3), 556.

[12]. Don, B. P., Girme, Y. U., & Hammond, M. D. (2019). Low self-esteem predicts indirect support seeking and its relationship consequences in intimate relationships. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 45(7), 1028-1041.

[13]. Huang, F. (2024). Constructing stay-at-home fathers’ work-care identities in China. The Journal of Men’s Studies, 10608265241257832.

[14]. Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A. G., & Buchner, A. (2007). G* Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior research methods, 39(2), 175-191.

[15]. Rosenberg, M. (1979). Conceiving the Self. New York: Basic Books.

[16]. Rusbult, C. E., Martz, J. M., & Agnew, C. R. (1998). The investment model scale: Measuring commitment level, satisfaction level, quality of alternatives, and investment size. Personal Relationships, 5, 357–387.

Cite this article

Han,Z. (2025). Silent Struggles: The Impact of Partner’s Refusal to Help on the Self-Esteem of Stay-at-Home Dads in Urban China. Lecture Notes in Education Psychology and Public Media,105,132-141.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Global Politics and Socio-Humanities

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Yuanchun, Du, & Lingwen, Gu, (2019, August 22). Becoming Stay-at-home Dads: Higher Acceptance by Male Interviewees than Female. www.Cyol.com. https: //zqb.cyol.com/html/2019-08/22/nw.D110000zgqnb_20190822_1-08.htm

[2]. Orth, U., & Robins, R. W. (2022). Is high self-esteem beneficial? Revisiting a classic question. American psychologist, 77(1), 5.

[3]. Luciano, E. C., & Orth, U. (2017). Transitions in romantic relationships and development of self-esteem. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 112, 307-328.

[4]. Murray, S. L., Holmes, J. G., & Griffin, D. W. (2000). Self-esteem and the quest for felt security: how perceived regard regulates attachment processes. Journal of personality and social psychology, 78(3), 478.

[5]. Jessica J., C., & Steve, G. (2018) Does Self-Esteem Have an Interpersonal Imprint Beyond Self-Reports? A Meta-Analysis of Self-Esteem and Objective Interpersonal Indicators, Personality and social psychology review : an official journal of the Society for Personality and Social Psychology, Inc, 23.1: 73-102.

[6]. Jayamaha, S. D., & Overall, N. C. (2019). The dyadic nature of self-evaluations: Self-esteem and efficacy shape and are shaped by support processes in relationships. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 10(2), 244-256.

[7]. Huang, F. (2023). Stay-at-home Fathers in Contemporary Urban China (Doctoral dissertation, University of Westminster).

[8]. Brennan, K. A., & Morris, K. A. (1997). Attachment styles, self-esteem, and patterns of seeking feedback from romantic partners. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 23(1), 23-31.

[9]. Auger, E., Thai, S., Birnie-Porter, C., & Lydon, J. E. (2024). On Creating Deeper Relationship Bonds: Felt Understanding Enhances Relationship Identification. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 01461672241233419.

[10]. Pelham, B. W., & Swann, W. B. (1989). From self-conceptions to self-worth: on the sources and structure of global self-esteem. Journal of personality and social psychology, 57(4), 672.

[11]. Murray, S. L., Rose, P., Bellavia, G. M., Holmes, J. G., & Kusche, A. G. (2002). When rejection stings: how self-esteem constrains relationship-enhancement processes. Journal of personality and social psychology, 83(3), 556.

[12]. Don, B. P., Girme, Y. U., & Hammond, M. D. (2019). Low self-esteem predicts indirect support seeking and its relationship consequences in intimate relationships. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 45(7), 1028-1041.

[13]. Huang, F. (2024). Constructing stay-at-home fathers’ work-care identities in China. The Journal of Men’s Studies, 10608265241257832.

[14]. Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A. G., & Buchner, A. (2007). G* Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior research methods, 39(2), 175-191.

[15]. Rosenberg, M. (1979). Conceiving the Self. New York: Basic Books.

[16]. Rusbult, C. E., Martz, J. M., & Agnew, C. R. (1998). The investment model scale: Measuring commitment level, satisfaction level, quality of alternatives, and investment size. Personal Relationships, 5, 357–387.