1. Introduction

Attachment styles are the ways through which people develop relationships and keep up emotional connections with their partners in relationships. This idea was inspired by the attachment theory, which was developed by John Bowlby [1] and Mary Ainsworth [2], to explain that the early relationships with caregivers have a significant impact on the formation of relationships in adulthood. In particular, according to attachment theory, people can be divided into four categories: secure, anxious, avoidant, and disorganized, depending on their strategy regarding proximity and security. Each type of people has different ways of behaving in relationships and society depending on their attachment style [3]. For instance, securely attached individuals have a high need for relationship distance but are low in insecurity. This normally ends up in producing solid and long-lasting relationships with other people. In contrast, anxious attachment means that the person has high insecurity with a strong desire for proximity. This often leads to a heightened fear of being rejected and a deep need for security, which prompts them to constantly seek reassurance and validation in their relationships. Avoidant attachment, on the other hand, is another style where people tend to avoid closeness. Those people have low insecurity but low desire for closeness as well. They try to avoid having intimate connections, maintaining autonomy over relationships, sometimes too much. Disorganized attachment presents a conflicting pattern. People with this style exhibit inconsistent patterns - high insecurity but low proximity seeking. Their behavior alternates between seeking closeness and withdrawing, which can create confusion in their relationships This occurs in friendships, romantic relationships, and the workplace to determine how people develop and sustain relationships.

People-pleasing behaviors, or in short pleasing behaviors, are actions aimed at gaining acceptance, avoiding conflict, or ensuring harmony in relationships. Individuals often regulate their behaviors to influence how they are perceived and presented [4]. Baumeister and Hutton [4] propose two motivations for self-presentations: audience pleasing and self-construction. Audience pleasing involves tailoring behaviors to meet others’ expectations, highlighting the influence of situational factors. While self-construction focuses on aligning behaviors with one’s ideal self, emphasizing internal personal consistency. Most people engage in both strategies depending on the circumstances. For example, individuals may agree to plans they are not completely satisfied with to avoid confrontation, while in other situations, they may defend their stance because it is important to them. However, people with anxious attachment styles exhibit higher levels of pleasing than secure attachment. Research suggests that secure individuals typically refrain from excessive people-pleasing due to well-established self-worthiness and self-esteem [5]. In contrast, anxious individuals often fear others’ rejection and seek validations to preserve their positive self-image, resulting in excessive self-sacrificing behaviors [5]. This can lead to emotional exhalations and mental health issues such as anxiety and depression [6].

Understanding how attachment styles influence people-pleasing and self-sacrificial tendencies is crucial, as it may help foster healthier interpersonal relationship and inform clinical interventions targeting psychological well-being. Our current research aims to explore these dynamics further by examining two dimensions: proximity-seeking and insecurity. Instead of using the traditional four arbitrary attachment categories, we explore the relationship between these two variables and how people engage in pleasing behaviors. Specifically, previous studies suggested that individuals with secure attachment (low insecurity, high proximity-seeking) exhibit less people-pleasing, while anxious individuals (high insecurity, high proximity-seeking) show more. We therefore hypothesize insecurity, rather than proximity-seeking, leads to pleasing behaviors and self-sacrificing. Additionally, we will investigate how family dynamics influence people’s insecurity and proximity-seeking. These explorations help illuminate the complex relationship between pleasing behaviors and attachment characteristics and how these traits are developed.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

Participants were recruited through social media using the online survey tool "Wenjuanxing." Initially, 45 individuals completed the survey, which comprised 43 questions. Specific details will be provided in subsequent sections. The exclusion criteria were: 1) age lower than 14 or larger than 60 years were excluded to target adolescents to adults; 2) completion time under 70 seconds were excluded to ensure adequate attention to each question; 3) participants who gave identical responses to all questions were excluded due to inattention.

The final cohort included 27 individuals aged 14 to 35 (M = 18.6, SD = 5.3), with 14 (51.9%) females. Seven (25.9%) participants had no siblings, 15 (55.6%) had one sibling, and five (18.5%) had two or more siblings. Regarding parent marital status, 20 (74.1%) participants had married parents, four (14.8%) had divorced parents, and three (11.1%) did not answer. Living arrangements included six (22.2%) living alone, four (14.8%) with one parent, 14 (51.9%) with both parents, and three (11.1%) with grandparents. In terms of parental relationships, 16 (59.3%) reported equal relationships with both parents, seven (25.9%) had better relationships with their mother, and four (14.8%) with their father.

2.2. Study design

Participants completed a comprehensive 43-question survey divided into three distinct sections: six questions on demographics, 15 on pleasing behaviors, and 22 on attachment styles. All questions were delivered in Mandarin. The demographic section collected data on age, gender, number of siblings, parent marital status, living arrangements, and relationship with parents, with statistics reported in the previous section. We collected information other than age and gender because we had exploratory interest to investigate whether pleasing behavior and attachments styles were related to environmental factors and family dynamics.

To evaluate pleasing behavior, due to the lack of existing literature directly addressing our focus, we adapted questions from self-sacrificing scales and developed our own measures (Appendix A). A total of 15 questions were designed. Participants rated how much they agreed with the statement on a five-point Likert scale: a) totally disagree, b) disagree, c) neutral, d) agree, and e) totally agree. Of these items, ten were positively framed to assess pleasing behaviors, while the remaining five were worded negatively. Scoring for the positive items was as follows: 1 = a), 2 = b), 3 = c), 4 = d), and 5 = e). In contrast, the negative items were scored inversely: 5 = a), 4 = b), 3 = c), 2 = d), and 1 = e). The total score was calculated by summing responses to all items. Scores ranged from 24 to 74 (M = 49.9, SD = 14.8), with higher scores indicating greater pleasing behaviors.

Attachment styles were evaluated using the Vulnerable Attachment Style Questionnaire (VASQ), focusing on two dimensions: proximity-seeking and insecurity [7]. Bifulco and colleagues [7] found VASQ reliable and valid, thus we have incorporated all questions. Of the 22 items, ten assessed proximity-seeking and 12 assessed insecurity. Participants rated their agreement on a 5-point Likert scale: 1 = totally disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = neutral, 4 = agree, and 5 = totally agree. Scores for proximity-seeking and insecurity were calculated by summing the relevant items. Proximity-seeking ratings ranged from 22 to 48 (M = 35.3, SD = 11.9), while insecurity ranged from 20 to 40 (M = 31.7, SD = 5.2). Higher scores indicated higher levels of proximity-seeking and insecurity.

2.3. Statistical analysis

A series of analysis was conducted to investigate the relationships among various variables using R (base package). Multiple regression examined the association between pleasing behavior and attachment styles measured by proximity-seeking and insecurity. Specifically, main effects of proximity-seeking, main effects of insecurity, and interaction between proximity-seeking and insecurity were included in the linear regression. According to our hypothesis, a null result of interaction and proximity-seeking main effect, but a significant insecurity main effect were expected. This is based on previous literature indicating that anxious attachment, rather than secure attachment, is most associated with pleasing behavior. These two attachment types largely differ in insecurity scales rather than proximity-seeking scales. Pearson’s correlation was used to further confirm these findings.

In addition to the main-hypothesis-driven multiple regression, two-sample t-tests and one-way ANOVAs were conducted to explore the effects of categorical demographic variables on pleasing behavior, proximity-seeking, and insecurity. Pearson’s correlation was conducted to investigate the impact of age on these variables.

3. Results

3.1. Influence of proximity-seeking and insecurity on between pleasing behavior

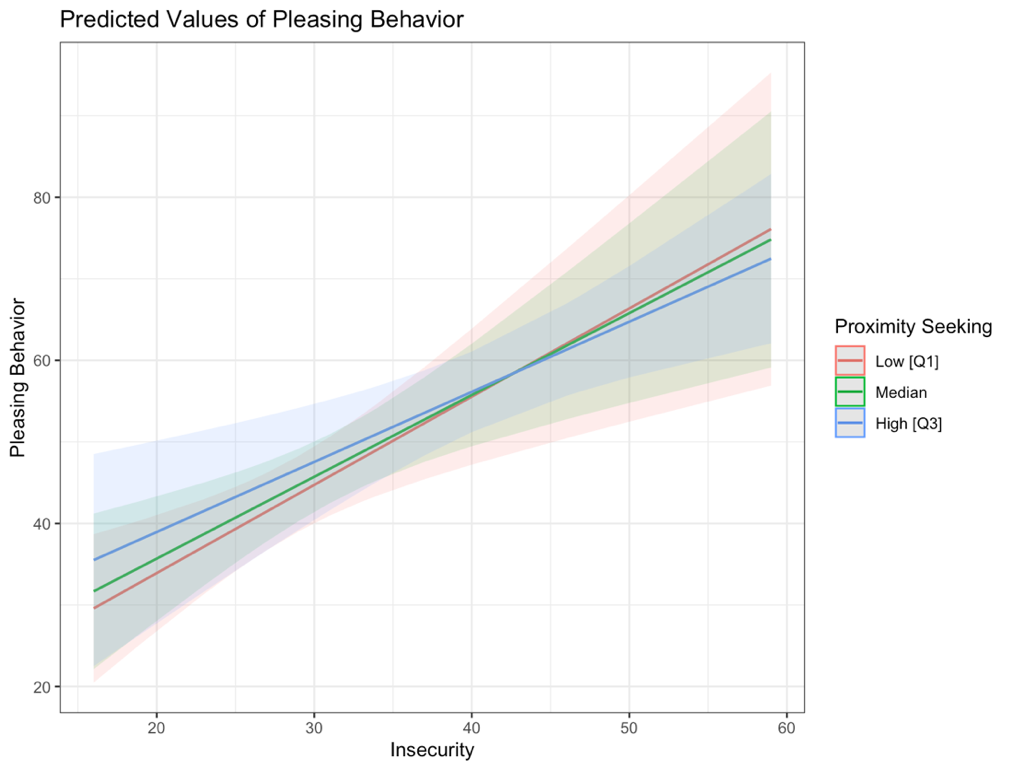

Multiple regression tested the interaction effect between proximity-seeking and insecurity on pleasing behavior (Figure 1). The analyses resulted in a significant multiple regression model (F(3, 23) = 11.56, p < 0.001, R2 = 0.60). The analysis revealed an insignificant interaction effect between proximity-seeking and insecurity on pleasing behavior (t(23) = -1.25, p = 0.22). However, a significant main effect of insecurity was observed (t(23) = 2.19, p = 0.039), while the main effect of proximity-seeking was not significant (t(23) = 1.32, p = 0.2). The results indicated that higher insecurity levels were associated with increased pleasing behaviors, regardless of proximity-seeking levels.

Notes: This illustrates the linear relationship between insecurity and pleasing behavior, segmented by three proximity-seeking levels: red (first quantile [Q1]), green (median), and blue (third quantile [Q3]). The overlapping regression lines indicate a non-significant interaction effect (i.e., the association is not dependent on proximity-seeking).

3.2. Relationship between age, pleasing behavior, and attachment styles

Pearson’s correlation analyses were further conducted to validate the relationship between pleasing behavior, proximity seeking, and insecurity, along with their association with age. The results are detailed in Table 1 below.

|

Age |

Pleasing Behavior |

Proximity Seeking |

Insecurity |

|

|

Age |

||||

|

Pleasing Behavior |

-0.32 |

|||

|

Proximity Seeking |

-0.44* |

0.76*** |

||

|

Insecurity |

-0.37 |

0.61*** |

0.76*** |

* p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001, Bonferroni-Holm corrected

Age did not exhibit significant correlation with pleasing behavior (p = 0.104) or insecurity (p = 0.069). But note that the relationship between age and insecurity was marginally significant (i.e., p < 0.1), indicating a trend (i.e., as individual age, they become more secure) that might become meaningful with a larger sample size and greater statistical power. Moreover, age demonstrated a significant negative linear relationship with proximity-seeking (r(25) = -0.44, p = 0.034), suggesting that as individuals grew older, their desire for proximity decreases.

Additionally, correlation analyses revealed significant positive linear relationships between pleasing behavior and both proximity-seeking (r(25) = 0.76, p < 0.001) and insecurity (r(25) = 0.61, p < 0.001). This result contrasted with the non-significant main effect of proximity-seeking found in the multiple linear regression main analysis. The discrepancy might be attributed to the high correlation between proximity-seeking and insecurity (r(25) = 0.76, p < 0.001), leading to potential multicollinearity issues. Additional analytical strategies may be necessary to disentangle the variance shared by these measures and address multicollinearity effectively.

3.3. Influence of familial factors on pleasing behavior, proximity seeking, and insecurity

None of the family dynamic factors (i.e., gender, number of siblings, parent marital status, living arrangements, and relationship with parents) significantly predict pleasing behavior (p > 0.05).

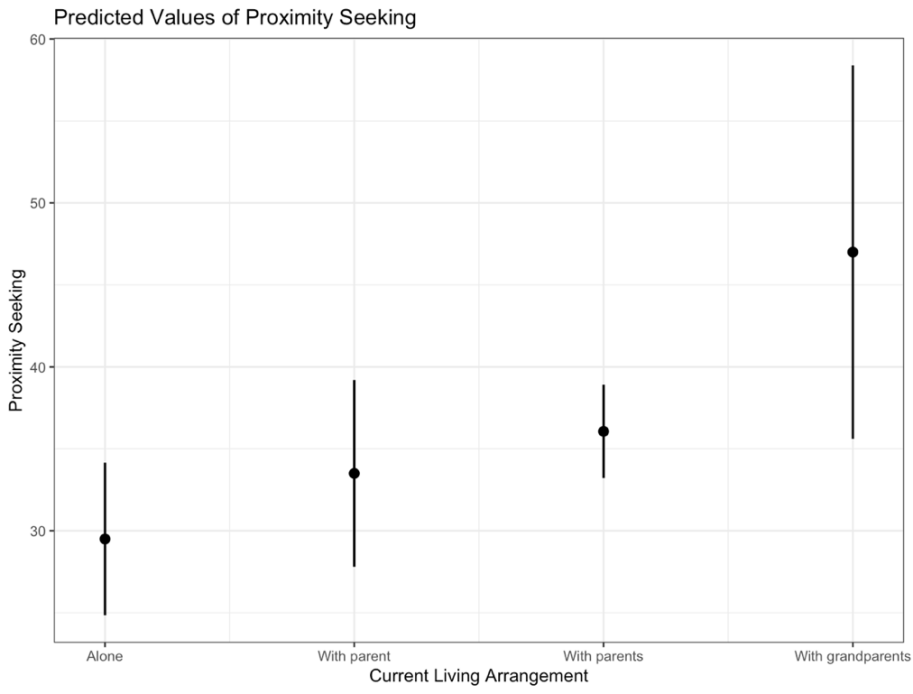

One-way ANOVA examined proximity-seeking suggested a statistically significant effect of currently living arrangements (Figure 2, F(3, 23) = 3.44, p = 0.033). Tukey’s Honest Significant Difference (HSD) post-hoc test was performed to identify pairwise differences between living arrangements groups. No other pairwise comparisons reached significance (p > 0.1), except for the difference between individuals living with grandparents (M = 47) vs. living alone (M = 29.5, p = 0.048), suggesting that participants living with grandparents desired significantly higher proximity compared to those living alone.

Notes: Proximity-seeking group means (indicated by dots) and standard error (represented by error bar) are shown for each living arrangements levels.

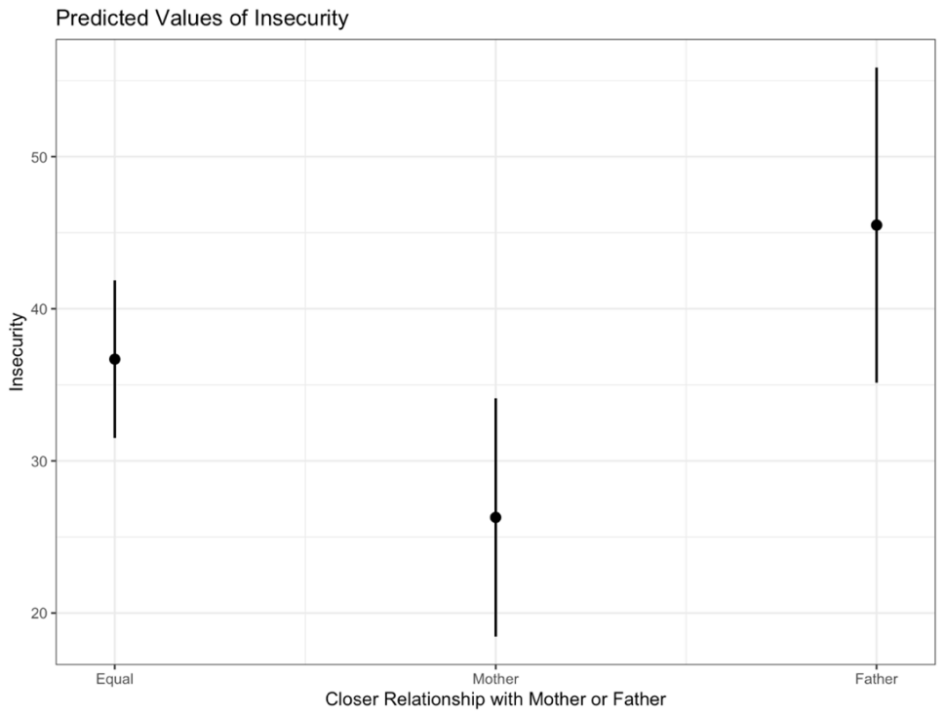

One-way ANOVA tested for insecurity suggested a statistically significant effect of relationship/closeness with parents (Figure 3, F(2, 24) = 4.54, p = 0.021). Post-hoc Tukey’s Honest HSD showed that participants who reported being closer to their father (M = 45.5) felt significantly more insecure than those closer to their mother (M = 26.3, p = 0.021), indicating that Other pairwise comparisons were not statistically significant (Equal – Mother: p = 0.097; Equal – Father: p = 0.313), suggesting that general closeness to both parents did not differ significantly in relation to insecurity levels.

Notes: Insecurity group means (indicated by dots) and standard error (represented by error bar) are shown for each levels of whether the participant is closer with mother or father.

4. Discussion

The present study aimed to examine the relationship between attachment-related dimensions, namely insecurity and proximity-seeking, and people-pleasing behavior. Consistent with our hypothesis and previous literature, we found that insecurity is a significant factor in pleasing behaviors, while proximity seeking does not show a direct influence. This suggests that individuals with higher insecurity, particularly those with anxious attachment styles, are more likely to engage in pleasing behaviors to gain acceptance and avoid rejection. Our current finding is consistent with a previous study done by Li [8], suggesting that individuals with anxious attachment prefer employ people-pleasing strategies as a mechanism to regulate interpersonal anxiety and maintain relational bonds. This finding shows the importance of addressing emotional insecurity in clinical to reduce negative pleasing behavior.

Interestingly, although proximity-seeking showed a strong positive correlation with pleasing behavior, it did not emerge as a significant predictor in the regression model. This discrepancy may be owing to the multicollinearity between insecurity and proximity-seeking, making it difficult to parse out their unique contributions. This issue reflects broader theoretical debates about the overlap between these constructs in attachment research [3]. Future research may benefit from statistical techniques like structural equation modeling (SEM) to parcellate shared variance and refine our understanding of how these dimensions function independently.

Age-related trends revealed that older participants reported lower proximity-seeking and marginally lower insecurity. This aligns with developmental theories suggesting that emotional regulation and secure attachment strengthen with age [9]. These findings hint at a potential maturation process where emotional needs for closeness become less intense, possibly due to increased self-reliance and internal security as people age.

Family dynamics also offered intriguing insights. Participants living with grandparents exhibited significantly higher proximity-seeking than those living alone, possibly reflecting the heightened emotional support associated with intergenerational caregiving. Conversely, individuals who reported greater closeness with their fathers showed higher insecurity than those closer to their mothers. This unexpected finding may reflect sociocultural norms around emotional expression, where maternal figures are often more associated with nurturing roles [10]. However, due to the limited sample size, future work should explore how parental emotional styles and gendered expectations influence attachment development.

5. Conclusion

This study provides evidence that emotional insecurity, more than proximity-seeking, predicts people-pleasing behavior. Our findings underscore the central role of internal attachment dynamics in shaping interpersonal tendencies. While proximity-seeking may reflect a desire for connection, it is insecurity that drives individuals to over-accommodate others. Age and family environment also influence these dynamics, highlighting the importance of developmental and contextual factors. These insights contribute to the broader literature on attachment and suggest potential avenues for interventions aimed at reducing maladaptive self-sacrificing behaviors.

References

[1]. Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and Loss: Volume 1. Attachment. New York: Basic Books.

[2]. Ainsworth, M. D. S., Blehar, M. C., Waters, E., & Wall, S. (1978). Patterns of Attachment: A Psychological Study of the Strange Situation. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

[3]. Mayseless, O. (1996). Attachment patterns and their outcomes. Human Development, 39(4), 206–223. https: //doi.org/10.1159/000278448

[4]. Baumeister, R.F., Hutton, D.G. (1987). Self-Presentation Theory: Self-Construction and Audience Pleasing. In: Mullen, B., Goethals, G.R. (eds) Theories of Group Behavior. Springer Series in Social Psychology. Springer, New York, NY. https: //doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4612-4634-3_4

[5]. Warnock, K.N., Ju, C.S. & Katz, I.M. A Meta-analysis of Attachment at Work. J Bus Psychol 39, 1239–1257 (2024). https: //doi.org/10.1007/s10869-024-09960-9

[6]. Murphy, B., & Bates, G. W. (1997). Adult attachment style and vulnerability to depression. Personality and Individual Differences, 22(6), 835–844. https: //doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(96)00277-2

[7]. Bifulco, A., Mahon, J., Kwon, J. H., Moran, P. M., & Jacobs, C. (2003). The Vulnerable Attachment Style Questionnaire (VASQ): An interview-based measure of attachment styles that predict depressive disorder. Psychological Medicine, 33(6), 1099–1110. https: //doi.org/10.1017/s0033291703008237

[8]. Li, Xintong. "How Attachment Theory Can Explain People-Pleasing Behaviors." Exploratio Journal (2022).

[9]. Sroufe, L. Alan. "Attachment and development: A prospective, longitudinal study from birth to adulthood." Attachment & human development 7.4 (2005): 349-367. https: //doi.org/10.1080/14616730500365928

[10]. Thompson, Ross A. "Attachment theory and research: Précis and prospect." The Oxford handbook of developmental psychology 2 (2013): 191-216.

Cite this article

Zhang,Y. (2025). The Role of Attachment Insecurity in People-Pleasing Behaviors. Lecture Notes in Education Psychology and Public Media,93,34-41.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of ICEIPI 2025 Symposium: Reimagining Society: AI's Role in Cultural Transformation and Learning Environments

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and Loss: Volume 1. Attachment. New York: Basic Books.

[2]. Ainsworth, M. D. S., Blehar, M. C., Waters, E., & Wall, S. (1978). Patterns of Attachment: A Psychological Study of the Strange Situation. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

[3]. Mayseless, O. (1996). Attachment patterns and their outcomes. Human Development, 39(4), 206–223. https: //doi.org/10.1159/000278448

[4]. Baumeister, R.F., Hutton, D.G. (1987). Self-Presentation Theory: Self-Construction and Audience Pleasing. In: Mullen, B., Goethals, G.R. (eds) Theories of Group Behavior. Springer Series in Social Psychology. Springer, New York, NY. https: //doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4612-4634-3_4

[5]. Warnock, K.N., Ju, C.S. & Katz, I.M. A Meta-analysis of Attachment at Work. J Bus Psychol 39, 1239–1257 (2024). https: //doi.org/10.1007/s10869-024-09960-9

[6]. Murphy, B., & Bates, G. W. (1997). Adult attachment style and vulnerability to depression. Personality and Individual Differences, 22(6), 835–844. https: //doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(96)00277-2

[7]. Bifulco, A., Mahon, J., Kwon, J. H., Moran, P. M., & Jacobs, C. (2003). The Vulnerable Attachment Style Questionnaire (VASQ): An interview-based measure of attachment styles that predict depressive disorder. Psychological Medicine, 33(6), 1099–1110. https: //doi.org/10.1017/s0033291703008237

[8]. Li, Xintong. "How Attachment Theory Can Explain People-Pleasing Behaviors." Exploratio Journal (2022).

[9]. Sroufe, L. Alan. "Attachment and development: A prospective, longitudinal study from birth to adulthood." Attachment & human development 7.4 (2005): 349-367. https: //doi.org/10.1080/14616730500365928

[10]. Thompson, Ross A. "Attachment theory and research: Précis and prospect." The Oxford handbook of developmental psychology 2 (2013): 191-216.