1. Introduction

The research determined how gender differences contribute to the experiencing of negative emotions such as sadness and anger. The work predicted that males would score higher on anger when exposed to irritation, while females would score higher on sadness when exposed to sorrowful situations.

The purpose of the experiment is to discover how gender differences contribute to the experiencing of negative emotions such as sadness and anger. Performing this study would help better interpret how banal gender roles still apply to nowadays society. Women had inferior status to men in the past thousands of years. With the thinking of the “cult of domesticity”–women should stay home taking care of their children and husbands without generating their own disobedient emotions– women unconsciously lost their capability to produce anger and were more linked to fragility. It had been stereotyped that woman were more sympathetic towards sad events, while men were angrier associated and were more likely to take part in antisocial behavior. This distinction is more obvious in real-life situations: husbands are the main physical abuser in a family [1]; however, women tend to cry more in the cinema when watching sad movies. To test this pattern, the research plans to find how further the stereotype applies in real-life conditions. It is predicted that males would be angrier when exposed to irritation, while females will be sadder when exposed to sorrowful situations.

The result corresponded to our hypothesis; women were more triggered by sadness while men more by anger. However, further experiments were encouraged to find if this trend applied to other circumstances rather than just for video clips.

2. Literature Review

Various studies have been made to examine this gender emotional stereotype, and most conclusions matched the trite pattern. For instance, according to Wang, when facing others' plight, women were more likely to assist people in difficulties while men mostly reflected indifferent attitudes [2]. Moreover, females required more emotional support (receiving help and endeavor help) from the same gender; however, men focused on themselves more and needed only tangible help from outside [3]. Those studies reflected those women and men had entirely different emotional needs and therefore had different attitudes to emotions. Furthermore, there was a study conducted by Choti and his fellow members in 1987 that evaluated the self-reported expression of sadness. It successfully conveyed the relationship between emotion, gender, and stereotype. Choti’s team measured expression on film-induced sadness by comparing self-report sadness and crying. They concluded that men retrospectively reported less crying than women, while females reported more concordance in the expression of crying and sadness [4]. Although personality differences between individuals accounted for the nuance between the same gender emotional expression, the big trend of females with sadness was well-founded. The hiding of males’ sadness can be explained by the long history of dissimilar gender roles, social status, and social impact. According to Brody, the long-existing social process caused men and women to express their emotions variously [5].

The topic interest was triggered by previous research of several specific personalities and gender. In the former experiment, Feingold looked for a correlation between gender and personality traits of self-esteem, extroversion, anxiety, trust, and nurture. Feingold found out that males tended to display more self-esteem and confidence than women. On the other hand, women reflected higher extroversion, anxiety, trust, and tenderheartedness than men [6]. Our experiment was inspired by Feingold’s study to discover unmentioned personality traits differences between men and women including anger and sadness.

Women would reflect more sympathy towards sad situations than men by prediction. According to a previous study from Peter and his colleagues, women reported a higher frequency of crying in both positive and negative conditions, which is often linked with emotional instability [7]. Therefore, this gender personality nurtural difference would contribute to the excessive sadness perceived by women.

Furthermore, men would probably express more anger than women. According to Campbell and Muncer, human beings reacted with either explosive acts (violent) or defusing acts (more peaceful acts) towards excitation, and the reaction is determined by gender. Men were more likely to perform explosive acts while women were more tended to exercise defusing acts. The aggression level of men was higher than women, meaning that men had a higher means to control over others [8]. Another research focused on gender-emotion stereotypes in context-specific testing. As stated by Kelly and Hutson-Comeaux, sadness and happiness were more associated with women while anger and pride were more linked with men. Kelly and her group tested happiness, sadness, and anger in different scenarios. The conclusion came out that women expressed overreaction in sadness and happiness in interpersonal contexts, while men expressed overreaction in anger in all scenarios [9]. However, this research contained certain drawbacks: The judges for overreaction levels were undergraduate students who were not authoritative. Also, there was no absolute clear standard for reaction level, therefore it was hard to tell what level is for overreaction. The experiment would follow up to determine this scenario by a brand-new implicit testing method to eliminate potential human error.

Implicit measurement was used to detect separately for female and male groups’ reactions towards angry and sad videotapes. All participants were shown by five same abstract images after watching the videotape and were asked to interpret the painter’s emotional state. In this way, participants would not know our true purpose is around videos rather than abstract pictures (details would be elaborated in following paragraphs).

Overall, according to previous research [10], gender differences in self-conscious emotions (SCE) such as guilt, shame, pride, and embarrassment existed. It showed that females tend to experience more negative emotions while males experience more pride. Thus, the study was interested in the specific negative emotions like sadness and anger, and how these emotions were perceived differently in males or females under the same situation. In general, it was hypothesized that females were more sensitive to sadness while males were more sensitive to anger.

The research would help us to interpret gender stereotypes and gender roles better. By finding out females’ and males’ different reaction levels towards sadness and anger videos, whether the old gender stereotype remained functioning in modern society could be found, and more comprehension would be given of opposite gender when facing stimulation.

3. Method

3.1. Participants

There will be 420 total participants of female and male in our experiment. 210 participants (105 females and 105 males) will be tested for one type of video (sad or angry) and another 210 participants will be tested for the other type. Using G Power, assuming an effect size Cohen’s d = 0.5 [11], the sample size will be 210 in each condition (105 females and 105 males), and the total sample size will be 420 participants to achieve a 95% statistical power.

3.2. Data exclusions

1. The participants data who identify themselves as cisgender will be excluded because this study will be conducted on cisgender only.

2. Participants under 18 who are without parental consent.

3.3. Unusual analyses

Our research will perform video comment selection, analyze the comments under videos and choose the best fit for each condition. Since there may be a very low percentage of participants who have entirely different perceptions after watching the video.

3.4. Research Design-Experimental setup

Participants will be randomly assigned to watch either one of the two short videos (one is about sadness and the other is about anger). After watching the video, each participant will be shown the same five abstract images and be asked to complete a survey.

3.5. Research Design-Survey setup

Participants chose their genders, followed by some videotape content questions to hide the real purpose of the research. Since participants did not know that their feelings towards the following pictures were influenced by the movie, the pictures following the videos would be a good method for blinding. In the end, participants would be asked to identify their perception of the painter’s emotional states from the following four choices: delight, sadness, anger, and tranquility. In order to evaluate emotional states better, they were asked to rate on a scale of 1-10 of the emotional level.

Thus, the design was a 2 (gender: male or female) x 2 (emotions: sadness and anger) factorial test, all between-subject design. Dependent variables were the rating from 1-10 of sadness and anger of the 5 pictures. In other words, it was the type of emotions the participants perceive on the 5 vague pictures after watching the video. This implicit emotion assessment task had been examined and supported by the previous study done by Bartoszek’s group [12]. According to the study, the feelings from watching the video would affect individual emotional judgment towards the vague pictures. After watching the video assigned, participants would then be asked to rate 5 abstract pictures and describe the pictures. They would be asked to complete a survey about the degree of sadness or anger on a scale from 1-10 about the picture (to hide our purpose to eliminate bias). For example, participants would be asked “What do you see in the picture; what kind of story is this picture telling you”While looking at the pictures. Our independent variable was gender type whom participants will be asked to identify their gender (male, female, or other)

4. Measures

To implicitly measure the participants' emotional level (anger and sadness), abstract image measurement was used to hide our purpose during the experiment. The research purpose was to find the difference of affectation state between males and females towards irritate and melancholy video clips. Two types of video clips (anger and sadness) were demonstrated to our participants and tested for their reaction levels. For implicit purposes, participants would not rate the video clip but instead would evaluate on a scale of 1-10 for abstract pictures’ emotional stage following the video clips. The research method was based on the previous study by Bartoszek and Cervone, who aimed at implicitly measuring the anger and fear by demonstrating participants first with an angry face, then with unfamiliar Chinese ideograph (served as a similar function to the abstract image). The participants would select the painter’s emotional state from several choices with a scale rating [11]. The principle of this implicit abstract pictorial measurement was that the judgments of the participants would be unconsciously impacted by their affection states. This heuristic emotional state method applying to our study would allow researchers to implicitly discover participants' real feelings about anger and sadness.

There were two essential elements in performing our implicit measurement. First of all, our participants would rate the artist’s emotional state for the five abstract pictures rather than letting the participants express their feelings about the pictures. This helped reduce bias since self-report could be inaccurate: participants may lie about their true feelings. Secondly, a scale rating of emotions was implemented with the same questions for every participant to eliminate exceptional feelings.

(This is an example of the type of abstract image we will use in this experiment):

Figure 1: Rorschach Inkblots model

Note: Figure 1 is an example of the abstract image that we implemented in our experiment. Those figure were unbiased an meaningless to reflect the real emotional stage of participants)

5. Procedure

420 participants were randomly assigned to watch either one of the two short videos (one is about sadness and the other is about anger). After watching the video, each participant was displayed five abstract images and were asked to identify the painter’s emotional stage on a scale of 1-10 for each image. Each image asked for one specific emotion to blend in our real motivation for testing anger and sadness (There will be a total of five emotions with five questions corresponding to five images and one for each). The question setup had a pattern of “how happy do you feel about this image?” For the five images, the study collected five questions in total inquiring about one emotion identification for each image. The five emotions included anger, sadness, fear, happiness, and tranquility. Finally, all data on anger and sadness questions (neglect all others) were selected and compared between males and females.

The research implemented an implicit research method to hide our real purpose, which was to test for participants' reactions towards the video clips. (It would appear to the participants that we are testing for abstract images). Finally, the participants’ responses towards the abstract images would unconsciously reflect their emotion stage triggered by the video clips.

6. Statistical analysis

Two independent samples T-tests were conducted to examine the emotional differences between female and male groups under each condition (anger and sadness). For each condition, the mean score of males and females was compared and then the mean differences were calculated to obtain the t value and the p-value. This helped to determine if there existed a significant difference between the means of the two gender groups. All data was put in Excel to analyze.

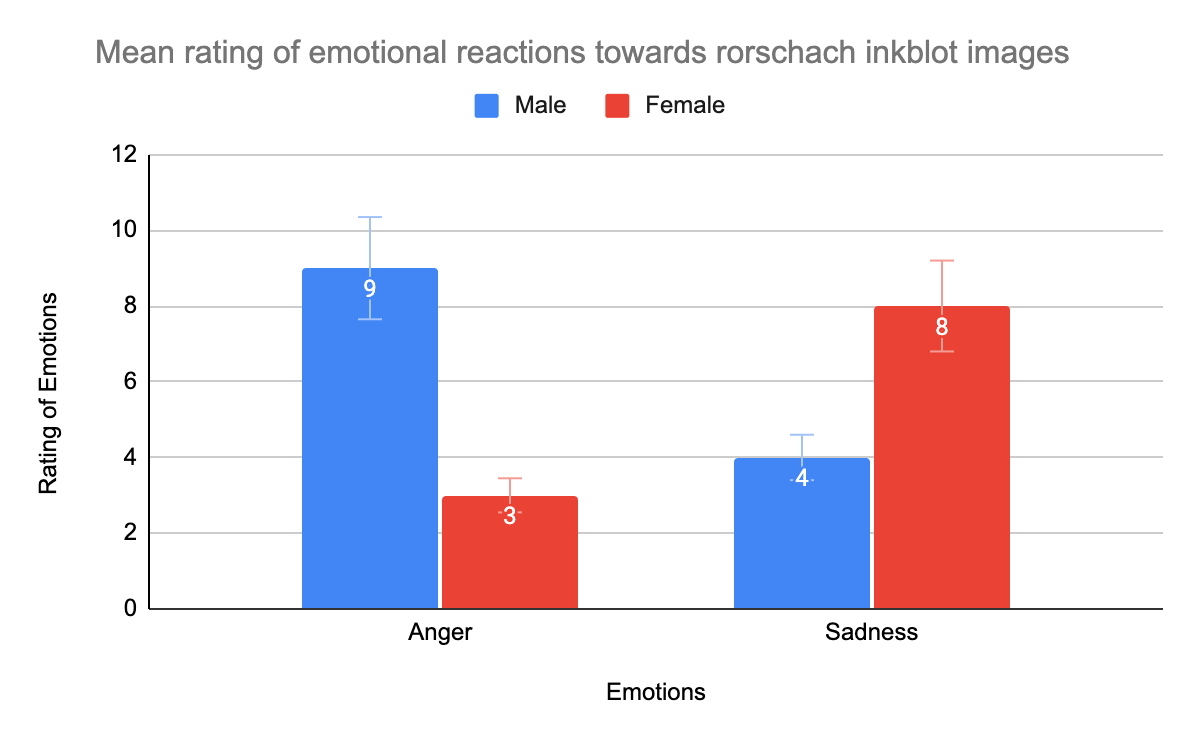

For the irritate video group, a two-tailed independent t-test showed that the males (M=9, SD=1.32) were rated as significantly higher than females (M=3, SD=1.06); t (104)=9.24, p< 0.001.

For the sad video group, a two-tailed independent t-test examined that females (M=8, SD=1.08) were rated significantly higher than males (M=4, SD=1.22), t (104)=7.43, p<0.001.

7. Results

Figure 2 (result on inkblot image)

Note: Figure 2 demonstrated the corresponding responses of the inkblot image (detailed in figure The men and women rated both on anger and sadness index.

From the data table, it was obvious that men had a higher average irritation score than women after watching mad videos, while women responded with more sadness than men after watching sorrowful videos. Specifically, after watching an irritating video clip, men reported an average irritation score of 9; however, females revealed an average score of 3, which is way lower than men. On the other hand, when males and females were both exposed to the sad video, females reported 4 points higher than men with an average sadness score of 8, while males had an average sadness score of 4.

8. Discussion

The experiment corroborates the general stereotype: females respond more sadly towards sad situations while males are more outraged under mad situations by analyzing their reactions toward anger and sad videos. This regulation helps us to notice the importance of gender roles and how the history of society shaped gender differences. Brody and his fellows in 1995 found out that women are fearful of producing anger in outrageous situations [5]. This dilemma may be caused by the gender roles stereotype that women should be tender mothers who are docile and obedient. Although this idea is not popular nowadays as educated citizens make the society more inclusive, the banal idea that has formed for hundreds of years yet changed–women are still in some circumstances characterized as “weaker” than men. Moreover, the research helps to understand the opposite gender's thinking better, men initially tended to produce anger while women were more likely to produce sadness. This nature and nurture difference should be understood in many circumstances such as at home, at work to produce a more peaceful relationship with each other.

8.1. Limitation and Future Directions

However, there are a few limitations to our experiment. The conclusion is tested on videos and can not fully be implied in other situations. There may be situations such as although men are irritated by angry videos, they are impassive towards angry photos.

8.2. Response Bias Limitation

Also, implicit measures may still contain small human-made errors. Although the work has lowered personal bias to the lowest level by letting participants report on an emotion scale rather than directly express their emotion (answers will be chaotic and varied), the participants can still hide their true feelings during the investigation process.

In the next step for future study, this emotional trend can be tested (females are sadder in sad situations and males feel more outraged in angry situations) in other circumstances (real-life social experiments). In this way can the extended applicability of this stereotype be discovered (women tended to experience more sadness and men tended to sense more outrages).

9. Conclusion

In conclusion, it can be confirmed that women would experience more sadness than men after watching sad video clips, while men will perceive more vexation than women after watching angry movies. By implementing the implicit measurement and assigning participants to respond to the video clips, the study corresponds to the gender stereotype of different sex perceiving negative emotions. It helps to understand the different gender roles in application to the society and to understand each other’s emotional state in order to assuage conflict in society. Women are more soft-hearted therefore participating more in chores, while men being more aggressive and firm are associated more with jobs. However, more research needs to be done to find out the application of this law to see if it only applies for watching video clips or in all real world situations.

References

[1]. [1] Domestic Violence Statistics. Shelter House. (2016, December 27). Retrieved November 14, 2021, from http://www.shelterhousenwfl.org/resources/domestic-violence-statistics/

[2]. [2] Wang, C. L. (2008). Gender differences in responding to sad emotional appeal: A moderated mediation explanation. Journal of Nonprofit & Public Sector Marketing, 19(1), 55–70. https://doi.org/10.1300/j054v19n01_03

[3]. [3] Reevy, G. M., & Maslach, C. (2001). Use of Social Support: Gender and Personality Differences. Sex Roles, 44(7/8), 437–459. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1011930128829

[4]. [4] Choti, S. E., Marston, A. R., Holston, S. G., & Hart, J. T. (1987). Gender and personality variables in film-induced sadness and crying. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 5(4), 535–544. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.1987.5.4.535

[5]. [5] Brody, L. R. (2010). Gender and emotion: Beyond stereotypes. Journal of Social Issues, 53(2), 369–393. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.1997.tb02448.x

[6]. [6] Feingold, A. (1994). Gender differences in personality: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 116(3), 429–456. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.116.3.429

[7]. [7] Peter, M., Vingerhoets, A. J. J. M., & Van Heck, G. L. (2001). Personality, gender, and crying. European Journal of Personality, 15(1), 19–28. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.386

[8]. [8] Campbell, A. and Muncer, S. (2008), Intent to harm or injure? Gender and the expression of anger. Aggr. Behav., 34: 282-293. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.20228

[9]. [9] Kelly, J. R., & Hutson-Comeaux, S. L. (1999). Sex Roles, 40(1/2), 107–120. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1018834501996

[10]. [10] Else-Quest, N. M., Higgins, A., Allison, C., & Morton, L. C. (2012). Gender differences in self- conscious emotional experience: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 138(5), 947–981. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027930

[11]. [11] Erdfelder, E., Faul, F. & Buchner, A. GPOWER: A general power analysis program. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers, 28, 1–11 (1996). https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03203630

[12]. [12] Gregory Bartoszek & Daniel Cervone (2017) Toward an implicit measure of emotions: ratings of abstract images reveal distinct emotional states, Cognition and Emotion, 31:7, 1377-1391, DOI: 10.1080/02699931.2016.1225004

Cite this article

Chen,M. (2023). The Role of Gender in Perceiving Emotions: Anger and Sadness. Lecture Notes in Education Psychology and Public Media,2,156-162.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Educational Innovation and Philosophical Inquiries (ICEIPI 2022), Part I

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. [1] Domestic Violence Statistics. Shelter House. (2016, December 27). Retrieved November 14, 2021, from http://www.shelterhousenwfl.org/resources/domestic-violence-statistics/

[2]. [2] Wang, C. L. (2008). Gender differences in responding to sad emotional appeal: A moderated mediation explanation. Journal of Nonprofit & Public Sector Marketing, 19(1), 55–70. https://doi.org/10.1300/j054v19n01_03

[3]. [3] Reevy, G. M., & Maslach, C. (2001). Use of Social Support: Gender and Personality Differences. Sex Roles, 44(7/8), 437–459. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1011930128829

[4]. [4] Choti, S. E., Marston, A. R., Holston, S. G., & Hart, J. T. (1987). Gender and personality variables in film-induced sadness and crying. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 5(4), 535–544. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.1987.5.4.535

[5]. [5] Brody, L. R. (2010). Gender and emotion: Beyond stereotypes. Journal of Social Issues, 53(2), 369–393. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.1997.tb02448.x

[6]. [6] Feingold, A. (1994). Gender differences in personality: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 116(3), 429–456. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.116.3.429

[7]. [7] Peter, M., Vingerhoets, A. J. J. M., & Van Heck, G. L. (2001). Personality, gender, and crying. European Journal of Personality, 15(1), 19–28. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.386

[8]. [8] Campbell, A. and Muncer, S. (2008), Intent to harm or injure? Gender and the expression of anger. Aggr. Behav., 34: 282-293. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.20228

[9]. [9] Kelly, J. R., & Hutson-Comeaux, S. L. (1999). Sex Roles, 40(1/2), 107–120. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1018834501996

[10]. [10] Else-Quest, N. M., Higgins, A., Allison, C., & Morton, L. C. (2012). Gender differences in self- conscious emotional experience: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 138(5), 947–981. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027930

[11]. [11] Erdfelder, E., Faul, F. & Buchner, A. GPOWER: A general power analysis program. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers, 28, 1–11 (1996). https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03203630

[12]. [12] Gregory Bartoszek & Daniel Cervone (2017) Toward an implicit measure of emotions: ratings of abstract images reveal distinct emotional states, Cognition and Emotion, 31:7, 1377-1391, DOI: 10.1080/02699931.2016.1225004