1. Introduction

During the coexistence of multiple ethnic regimes, the Khitan rulers adopted an inclusive attitude toward Confucianism, Buddhism, and Taoism from the founding of their state to accommodate the needs of ruling a multi-ethnic population. From the founding of the Liao state, they implemented a policy of "coexistence of the three religions." A typical example is the "Three Elders Playing Chess" mural unearthed from the Liao Dynasty tomb of Zhang Wenliao in Xuanhua, Hebei. The central figure wears a futou headwear with hard flaps, a common headgear for Song Dynasty officials in formal attire, and a traditional Chinese robe, identifying him as a Confucian scholar. The two players include a Taoist with a topknot and long robe on the left and a bald Buddhist monk on the right, symbolizing the convergence of Confucianism, Buddhism and Taoism [1]. In the early Liao period, rulers constructed Taoist temples. By the mid-to-late Liao period, due to rulers’ devout belief in Taoism and their obsession with ascension and immortality, Taoism further developed. Against this backdrop, Khitan tombs from the Liao Dynasty contain numerous Taoist elements. For instance, murals depict motifs such as Taoist priests, the "yin-yang fish," door gods, and cranes. Burial objects feature images of Taoist immortals and designs symbolizing ascension to immortality. Additionally, the selection of tomb sites reflects Taoist doctrines of yin-yang theory and the philosophy of celebrating life while mourning death.

Previous research on the religious influences reflected in Khitan tombs is extensive. For instance, Yu Bo studied the impact of Buddhism on Liao Dynasty burial practices through the lens of portrait statues [2]; Du Xiaofan explored the relationship between Khitan tombs and shamanism via masks and nets [3], Guo Aobo provided a general analysis of the Buddhist, Taoist, and shamanistic elements in Liao tombs [4]; while Zhang Mingxing and Su Xiaoming examined the shift from shamanism to Buddhism in Liao tomb art [5]. Overall, prior studies primarily focused on shamanism or Buddhism's influence on Khitan tombs or offered generalized analyses of the religious beliefs reflected in Khitan tombs, with limited or superficial attention to Taoism’s impact. This paper specifically analyzes Taoist influences on Khitan tombs to elucidate the Khitan people's Taoist beliefs. The study aims to deepen our understanding of Khitan culture, reveal their spiritual world, provide new insights for Khitan historical research, and promote cultural exchange and development.

2. Taoism and the Khitan

2.1. Transmission and development of Taoism

Taoism first came into contact with the Khitan during the Five Dynasties period. Following the establishment of the Liao Dynasty, Han migrants fleeing turmoil brought Taoism to Khitan territories, where it gradually developed under the policy of 'the coexistence of the three religions’. The reigns of Emperor Shengzong and Xingzong marked the peak of Taoism’s influence in the Liao Dynasty. However, its prominence waned in the late Liao period as peasant uprisings often adopted Taoist banners. The Tang Dynasty’s promotion of Taoism facilitated its spread in northern regions, and the patronage of Five Dynasties rulers and northern military governors familiarized the Khitan with Taoism.

As a multi-ethnic state, the Liao Dynasty implemented segregation policies and absorbed Han culture to stabilize rule and mitigate ethnic tensions, enabling the spread of Taoist culture. In the third year of the Shence (918 CE), shortly after the Liao’s founding, the first emperor of Liao (Yelü Abaoji) decreed the construction of Confucian temples, Buddhist monasteries, and Taoist temples, adopting the Tang Dynasty's strategy of the policy of the coexistence of the three religions to reconcile ethnic tensions [6]. Taoism was also used to mythologize Khitan founding history, merging its "unity between heaven and humanity" concept with traditional Khitan nature worship to legitimize Liao rule [7]. Subsequent Liao rulers included Taoism enthusiasts, with Shengzong and Xingzong exerting the greatest influence. Shengzong appointed the Taoist priest Feng Ruogu as "Zhongyun of the Crown Prince"(The important officials serving beside the crown prince, primarily responsible for ceremonial attendance, refuting and correcting memorials, and other administrative affairs.), not only to satisfy his pursuit of immortality but also serve as a counterbalance to Buddhism, preventing it from becoming overwhelmingly dominant [6]. Meanwhile, Taoism had a certain influence on the Han people. By promoting Taoist priests, the Emperor also sought to win over and unite the Han officials in the Liao court, thus continuing the initial positioning of Taoism at the establishment of the Liao Dynasty [7]. Feng Ruogu, as a Taoist overseeing crown prince rituals and communications, significantly influenced the future Emperor Xingzong. Xingzong, an even more ardent Taoist, appointed many priests as officials and had imperial consorts dress as Taoist nuns. Their patronage provided strong impetus for Taoism's development [8].

Liao rulers promoted Taoism and other religions by constructing temples, expanding Taoism's reach and legitimizing its propagation. Over nearly a century, though never surpassing Buddhism, Taoism influenced Khitan society: the aristocracy, superstitious about ascending to heaven and longing for immortality, revered the Taoist theories of Yin-Yang and Feng Shui, placing great emphasis on the selection of burial sites, which also exerted a certain influence on the common populace [9]. Archaeological discoveries reveal secularized Taoist beliefs in Liao tombs, such as murals depicting ascetic practices, crane-riding ascension, and door gods. Taoism upholds the principle of "valuing life and detesting death" and envisions "immortality and deification" as the ideal existential state. Since death is inevitable, Taoist practitioners engage in various cultivation methods such as alchemy, divination, and meditation in an attempt to achieve either physical immortality or spiritual transcendence. These aspirations are reflected in the imagery of Taoist meditation in tomb murals and depictions of riding cranes to ascend to the heavens on burial objects.

2.2. Khitan Tombs influenced by Taoism

2.2.1. The joint tomb of Princess Chen and her husband

Discovered in Qinglongshan Town, Naiman Banner, Tongliao, Inner Mongolia, this tomb is the most intact and richly furnished Khitan aristocratic burial found to date. The epitaph records that Princess Chen, a granddaughter of Emperor Jingzong, was enfeoffed as Princess of Yue during the Taiping era and later received additional titles. The emperor's personal concern during her illness reflects her exalted status [10].

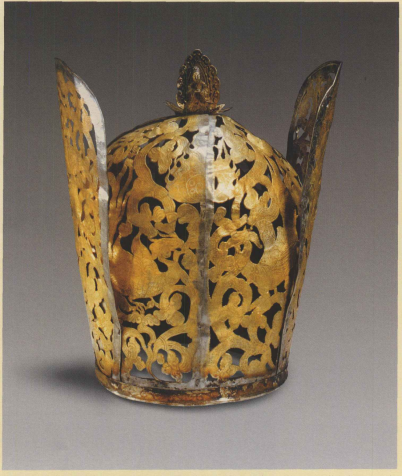

The tomb contained two gilded silver crowns. One of them, belonging to the princess, features a central perforation with a gilded silver statuette of Yuanshi Tianzun(The Primeval Lord of Heaven) (Fig. 1). The deity wears a Taoist crown, sports a long beard, and sits cross-legged in voluminous robes. As the foremost of Taoism's "San Qing" (The Three Pristine Ones), Yuanshi Tianzun symbolizes cosmic origin and creation, with his presence signifying His image appearing in tombs signifies "initiating kalpas to deliver souls", which means guiding the deceased to transcend the boundaries of life and death, return to the cosmic origin, and achieve liberation from the cycle of reincarnation. His existence implies the possibility for the deceased to reconstruct the order of life in the underworld.

The other item is the consort’s crown, which also features a Taoist statue at its center—Zhenwu Dadi(The Black Warrior Thearch). Depicted wearing wide robes with long sleeves, a lotus crown on his head, and standing while leaning on a staff, Zhenwu Dadi is the supreme deity guarding the north in Taoism. His functions encompass protecting the Dharma, subduing demons, eliminating calamities, and safeguarding all living beings. The presence of his image in the tomb aims to ward off malevolent spirits, prevent the deceased soul from being disturbed, and ensure the tomb's tranquility. Zhenwu Dadi represents the characteristics of the northern water deity, whose divine influence aids the departed soul in across the underworld river (symbolizing the demarcation between yin and yang, life and death) to facilitate a seamless transition into the underworld trial or reincarnation process. Before the illustrious Emperor Zhenwu, a turtle bears a serpent entwined upon its shell. Within the Taoist religious framework of the Liao and Song dynasties, the turtle and snake serve as the two generals under the leadership of the Great Emperor Zhenwu. They function both as Dharma protectors and as his mounts, representing the equilibrium of water and fire, alongside the retribution of malevolence and the advancement of virtue. These personalities were significant mediums for propagating Taoist secular principles. The two gilded silver crowns closely resemble the functional headwear of Khitan nobility during the Liao Dynasty in terms of form, and their nature should be classified as funerary objects specifically made for burial purposes. These two gilded silver crowns could serve as religious "sacred artifacts" for communicating between humans and deities, guiding the deceased’s soul to ascend to the heavenly realm. The Taoist deities Primordial Heavenly Venerable and True Martial Emperor depicted at the crown's apex function as the communicators and guides—these are precisely the Taoist deities represented on the crowns [11]. Yuanshi Tianzun represents the Cosmic Order (Tiandao), symbolizing the supreme principle of cosmic generation; the True Martial Emperor symbolizes the Terrestrial Order (Didao). Their combination embodies the Daoist cosmological view of "the unity between Heaven, Earth, and Humanity," emphasizing that the deceased must align with the natural laws to complete the cycle of life and death. The presence of Daoist worship and burial objects featuring Daoist deities in the highly esteemed tomb of Princess Chenguo sufficiently demonstrates the profound influence of Daoism on the Khitan nobility.

2.2.2. Other aristocratic tombs

2.2.2.1. Beipiao Jizhangzi Liao dynasty painted tomb

Judging from the grand architectural style of the burial chamber, the wooden-imitation lintel, the cypress wood protective walls, and the stone reinforcements on the outer roof, this tomb was constructed at enormous expense, clearly indicating the Khitan noble status of its occupant. The murals inside the tomb exhibit distinct Taoist elements, with male attendants dressed in attire featuring Taoist motifs. In the Procession of Attendants mural, five pairs of figures are depicted on the left and right walls of the tomb passage. Among them, all eight male figures wear the traditional Khitan "tonsured" hairstyle—completely shaved on the crown with long, slender sideburns flowing past the ears. Their garments are adorned with the Taoist "Yin-Yang fish" symbol.

During the Liao and Song periods, the "Yin-Yang fish" had not yet fully evolved into the familiar "double fish" form seen in later eras. Instead, it was represented through an interlocking black-and-white circular structure, embodying the interdependence of yin and yang and forming a preliminary dynamic cyclical pattern that expressed the philosophical logic of Wuji giving rise to Taiji. This is regarded as the embryonic form of the yin-yang fish motif. Cranes in flight and drifting clouds, interspersed among the figures, create a Taoist celestial paradise for the tomb owner, symbolizing aspirations for the soul to ascend to the heavenly realm after death—a core Taoist belief [13].

2.2.2.2. Fuxin Guanshan Liao tombs

The Guan Mountain Liao Tombs consist of nine brick-chambered tombs, serving as the burial grounds of the Xiaohe family. The Xiao clan held a highly prestigious position in the Liao Dynasty, with nearly all empresses originating from this lineage. As founding contributors to the dynasty, members of the Xiao clan assumed key official roles and made significant contributions to the Liao state. Both the site selection of the Guan Mountain Liao Tombs and their murals reflect the influence of Daoism on the Khitan nobility.

The selection of the tomb location utilized geomantic ideas established in the Central Plains during the Tang and Song Dynasties, with a significant focus on the theories of yin-yang and feng shui. According to the Northern Song official text The New Book of Geography, an ideal burial site (referred to as "supremely auspicious land") should have mountain ridges as a protective barrier behind the tomb, water bodies in front, and continuous mountain ranges and watercourses extending for hundreds of miles to embody the integrity of the "dragon vein" and the coherence of the energy field [14]. The Guan Mountain area lies at the northeastern foothills of the Yiwulü Mountain range, adjacent to the Liao River, both of which stretch continuously for hundreds of miles, making it a supremely auspicious location that demonstrates the Khitan nobility's reverence for Daoist yin-yang and feng shui principles.

In Tomb No. 1 of the Guan Mountain Liao Tombs, the mural in the tomb of Xiao Dewen features a "Daoist Cultivation Scene." The Daoist practitioner, dressed in traditional Khitan attire and a long robe, is shown meditating on a square stone, with a long sword planted before him. In Daoist culture, swords are not merely weapons for self-defense but also ritual instruments used to ward off evil, vanquish demons, and sever inner demons. Beside the figure stands a three-tiered square platform holding three incense sticks. Burning incense in Daoism serves as a means to convey wishes and seek divine blessings, with the three sticks symbolizing the "Three Powers" of heaven, earth, and humanity. Heaven represents cosmic rhythms such as seasonal cycles and the alternation of day and night; earth signifies material foundations like mountains, rivers, and soil; and humanity embodies ethical principles such as benevolence and righteousness, harmonizing natural laws through moral practice. This imagery vividly reflects the Daoist pursuit of cosmic unity and the coexistence of all beings.

In Tomb No. 3, the joint burial site of Xiao Zhixing and his wife, red-crowned cranes are painted on the passage walls of the tomb gate, while Daoist priests holding objects are depicted in the small niches on the northern and southern sides. Daoism centers on the pursuit of longevity and immortality, and the crane, due to its legendary "thousand-year lifespan," became a symbolic representation of "eternal life," embodying the ultimate aspiration of practitioners to prolong life. Moreover, the crane’s soaring flight aligns with the Daoist ideal of "ascending to immortality through feather transformation." Its image—"soaring above the clouds, transcending worldly concerns"—is regarded as a manifestation of mortals ascending to the celestial realm. Cranes frequently appear as divine mounts in mythology, often serving as vehicles for immortals. Legends of riding cranes to ascend to heaven reinforce their role as "guides to the immortal realm." These murals illustrate the tomb occupants’ devotion to Daoist philosophy [15].

3. Discussion

This study identified a non-aristocratic Khitan tomb containing Taoist elements—the Liao Dynasty tomb at Erlinchang, Tongliao, Inner Mongolia. The Liao Dynasty inherited the Tang system. Based on the nine belt plaques (ornamental rings on the waistband used to hang bows, arrows, swords, and knives) unearthed from the tomb, it was determined that the tomb owner held a civil official rank of sixth or seventh grade. The gilded bronze fish excavated from the tomb should reflect the Liao Dynasty's adoption of the Tang Dynasty’s fish tally system, indicating the occupant’s position was higher than sixth grade. Additionally, a tri-colored ceramic pillow was excavated, depicting a figure riding a large bird on both sides, surrounded by streamlined cloud patterns, portraying a scene of human flight [16]. This imagery alludes to the Taoist legend of immortal Wang Qiao ascending to heaven on a white crane, embodying the Taoist concept of riding a crane to the "celestial realm."[9]

However, this study find that Taoist-influenced Khitan tombs are predominantly aristocratic, with far fewer non-aristocratic examples. While this discrepancy may partly stem from the limited preservation and fewer burial artifacts in non-aristocratic tombs—hindering a full representation of the occupants’ beliefs—it could also suggest that Taoism's influence on the Khitan people was largely confined to the nobility. Taoism's development during the Liao Dynasty relied primarily on imperial patronage. With the exception of Emperors Shengzong and Xingzong, other sovereigns had minimal interest in Taoism. Buddhism's focus on karma and reincarnation facilitated government, but post-Xingzong peasant uprisings sometimes embraced Taoism as a cohesive belief system, leading rulers to intensify its suppression. Taoism experienced a brief period of prosperity during the Liao era, with minimal influence among non-aristocratic classes, whose beliefs continued to be anchored in shamanism and Buddhism. Consequently, the influence of Taoism on non-elites was negligible.

4. Conclusion

This study demonstrates that Taoism’s influence on the Khitan people was largely confined to the aristocracy. Elite tombs feature murals of spiritual cultivation, visions of posthumous Taoist paradises, and burial items invoking divine guidance for the deceased, all reflecting a yearning for immortality and celestial transcendence. Geomantic site selection further reveals desires for enduring familial fortune and ancestral blessings. While Daoist motifs do occasionally appear in non-aristocratic tombs—such as the Erlianchang Liao Tomb—such instances remain relatively rare. Due to space constraints, this article cannot exhaustively catalog all Taoist-associated tombs, highlighting the need for further in-depth and systematic research.

References

[1]. 1999. Reading of the Mural Paintings of the Liao dynasty Tombs. Cultural Relics.

[2]. Yu Bo. (2018). The Influence of Buddhism on the Funerary Customs of the Liao Dynasty as Seen through True Likeness Statues. Northern Cultural Relics, (02), 91-95. doi: 10.16422/j.cnki.1001-0483.2018.02.015.

[3]. Du Xiaofan. (1987). The Relationship Between Masks, Networks, and Shamanism in the Burial Customs of the Khitan Ethnic Group—Also a Discussion with Comrade Ma Honglu.Ethno-National Studies, (06), 77-84.

[4]. Guo Aobo. (2021). A Brief Analysis of Religious Beliefs Reflected in Liao Dynasty Tombs.Identification and Appreciation to Cultural Relics, (13), 66-69.

[5]. Zhang Mingxing & Su Xiaoming. (2022). From Shamanism to Buddhism: A Preliminary Study on the Evolution of Religious Elements in the Funerary Art of the Liao Dynasty.Journal of Inner Mongolia Arts University, 19(03), 135-144.

[6]. Yuan Tuotuo. 1974. : History of Liao), Beijing: Zhonghua Shubu.

[7]. Du Xing. (2022). A Study on Religious Beliefs During the Reigns of Emperor Shengzong and Xingzong of Liao(Master's Thesis, Inner Mongolia University for Nationalities). Master https: //link.cnki.net/doi/10.27228/d.cnki.gnmmu.2022.000100doi: 10.27228/d.cnki.gnmmu.2022.000100.

[8]. Zheng Yonghua. (2013). A Preliminary Study on Taoism in Yanjing During the Liao Dynasty.Journal of Beijing Union University(Humanities and Social Sciences), 11(02), 55-58. doi: 10.16255/j.cnki.11-5117c.2013.02.008.

[9]. Zheng Yi. (2010). The Status and Role of Confucianism, Buddhism, and Taoism in the Liao Dynasty. History and Archaeology of the Liao and Jin Dynasties, (00), 187-201.

[10]. Sun Jianhua & Zhang Yu. (1987). Excavation Brief of the Joint Tomb of Princess Chen and Her Consort of the Liao Dynasty. Cultural Relics, (11), 4-24+97-106.

[11]. Sun Meng. (2010). Archaeological Investigation of Taoist Culture and Beliefs in the Liao Dynasty. China Taoism, (05), 34-37. doi: 10.19420/j.cnki.10069593.2010.05.014.

[12]. Suo Xiufen. (2004). Cultural relics from the joint burial tomb of Princess Chen of Liao and her consort. Rong Baozhai, (03), 44-49. doi: 10.14131/j.cnki.rbzqk.2004.03.003.

[13]. Han Baoxing. (1995). Beipiao Jizhangzi Liao Dynasty Mural Tomb.Liaohai Cultural Relics Journal, (01), 149-156+282-283.

[14]. Wang Su, 1985. A New Book of Illustrated and Corrected Geography, Taipei.

[15]. Liaoning Provincial Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology, 2011. Guanshan Liao Tomb [M]. Cultural Relics Publishing House.

[16]. Zhang Baizhong. (1985). Liao Dynasty Tomb at Erlinchang, Tongliao County, Inner Mongolia.Cultural Relics, (03), 56-62.

Cite this article

Liu,Y. (2025). Analysis of the Influence of Taoism on Khitan Tombs. Lecture Notes in Education Psychology and Public Media,100,228-234.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of ICEIPI 2025 Symposium: Understanding Religious Identity in Educational Contexts

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. 1999. Reading of the Mural Paintings of the Liao dynasty Tombs. Cultural Relics.

[2]. Yu Bo. (2018). The Influence of Buddhism on the Funerary Customs of the Liao Dynasty as Seen through True Likeness Statues. Northern Cultural Relics, (02), 91-95. doi: 10.16422/j.cnki.1001-0483.2018.02.015.

[3]. Du Xiaofan. (1987). The Relationship Between Masks, Networks, and Shamanism in the Burial Customs of the Khitan Ethnic Group—Also a Discussion with Comrade Ma Honglu.Ethno-National Studies, (06), 77-84.

[4]. Guo Aobo. (2021). A Brief Analysis of Religious Beliefs Reflected in Liao Dynasty Tombs.Identification and Appreciation to Cultural Relics, (13), 66-69.

[5]. Zhang Mingxing & Su Xiaoming. (2022). From Shamanism to Buddhism: A Preliminary Study on the Evolution of Religious Elements in the Funerary Art of the Liao Dynasty.Journal of Inner Mongolia Arts University, 19(03), 135-144.

[6]. Yuan Tuotuo. 1974. : History of Liao), Beijing: Zhonghua Shubu.

[7]. Du Xing. (2022). A Study on Religious Beliefs During the Reigns of Emperor Shengzong and Xingzong of Liao(Master's Thesis, Inner Mongolia University for Nationalities). Master https: //link.cnki.net/doi/10.27228/d.cnki.gnmmu.2022.000100doi: 10.27228/d.cnki.gnmmu.2022.000100.

[8]. Zheng Yonghua. (2013). A Preliminary Study on Taoism in Yanjing During the Liao Dynasty.Journal of Beijing Union University(Humanities and Social Sciences), 11(02), 55-58. doi: 10.16255/j.cnki.11-5117c.2013.02.008.

[9]. Zheng Yi. (2010). The Status and Role of Confucianism, Buddhism, and Taoism in the Liao Dynasty. History and Archaeology of the Liao and Jin Dynasties, (00), 187-201.

[10]. Sun Jianhua & Zhang Yu. (1987). Excavation Brief of the Joint Tomb of Princess Chen and Her Consort of the Liao Dynasty. Cultural Relics, (11), 4-24+97-106.

[11]. Sun Meng. (2010). Archaeological Investigation of Taoist Culture and Beliefs in the Liao Dynasty. China Taoism, (05), 34-37. doi: 10.19420/j.cnki.10069593.2010.05.014.

[12]. Suo Xiufen. (2004). Cultural relics from the joint burial tomb of Princess Chen of Liao and her consort. Rong Baozhai, (03), 44-49. doi: 10.14131/j.cnki.rbzqk.2004.03.003.

[13]. Han Baoxing. (1995). Beipiao Jizhangzi Liao Dynasty Mural Tomb.Liaohai Cultural Relics Journal, (01), 149-156+282-283.

[14]. Wang Su, 1985. A New Book of Illustrated and Corrected Geography, Taipei.

[15]. Liaoning Provincial Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology, 2011. Guanshan Liao Tomb [M]. Cultural Relics Publishing House.

[16]. Zhang Baizhong. (1985). Liao Dynasty Tomb at Erlinchang, Tongliao County, Inner Mongolia.Cultural Relics, (03), 56-62.