1. Introduction

1.1. Empathy

Empathy is a central topic in the field of positive psychology and serves as the foundation for building healthy interpersonal relationships. In previous research, scholars have commonly defined empathy from both affective and cognitive perspectives. From the affective perspective, empathy is regarded as an emotional response that an individual has to the experiences of others [1]. Some scholars view empathy as an emotional alignment with others, encompassing feelings such as sympathy, compassion, and tenderness—emotions that are consistent with others' emotional states and well-being [2]. Others define empathy as the capacity to share and understand another person’s experiences and emotions. Specifically, this refers to an emotional state within the individual that arises from observing or imagining another’s emotional condition, with the individual being aware that their emotional response is elicited by the other's emotional state [3-4]. From the cognitive perspective, empathy is understood as a decentering process in which one steps outside of one’s own viewpoint and mentally adopts the perspective of another—an act of perspective-taking within another’s situational context [5,6].

1.2. Intimate relationships

The definition of intimate relationships can be categorized into narrow and broad senses. In the narrow sense, intimate relationships primarily refer to romantic or dating relationships, in which the individuals involved are often referred to as partners. In the broad sense, intimate relationships encompass various types of connections characterized by a high degree of emotional interdependence, including romantic relationships, marital relationships, familial ties, peer relationships, and friendships [7]. Additionally, some foreign scholars argue that intimate relationships can also be viewed as collaborative and mutually attuned partnerships. Such relationships require a foundation of trust, enabling individuals with differing needs and life goals to gradually establish relational stability and shared goals of intimacy through a process of mutual adjustment and compromise [8].

In the context of Chinese culture, intimate relationships are often characterized by a strong automatic empathic process. Due to a high degree of self–other integration, individuals tend to experience empathy in the form of emotional distress or pain [9]. Furthermore, studies have found that women generally exhibit higher levels of affective empathy than men. Women's empathic responses are more significantly influenced by the nature of the intimate relationship, showing greater empathy toward romantic partners—an effect that is not observed among men [10].

1.3. Measurement of empathy

There are various methods for measuring empathy across different dimensions and target groups. The most commonly used methods include self-report, observer ratings, and experimental induction. Given the objectives of this study, the focus will be on reviewing empathy measurement approaches based primarily on psychometric scales.

One of the primary tools for measuring self-reported empathy is the Interpersonal Reactivity Index (IRI), which was developed based on the multidimensional theory of empathy. The IRI consists of 22 items rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (does not describe me well) to 4 (describes me very well), with higher scores indicating a higher level of empathy. The scale comprises four subscales: Perspective Taking (PT): measures the tendency of individuals to spontaneously adopt the psychological viewpoint of others; Fantasy Scale (FS): assesses the tendency to imaginatively transpose oneself into the feelings and actions of fictional characters; Empathic Concern (EC): evaluates the tendency to experience feelings of sympathy and concern for others in distress, reflecting an “other-oriented” emotional response; Personal Distress (PD): measures the feelings of anxiety and discomfort that arise during tense interpersonal situations, reflecting a “self-oriented” emotional response. Among these, Perspective Taking and Fantasy are categorized under cognitive empathy, while Empathic Concern and Personal Distress fall under emotional empathy. However, the IRI remains subject to ongoing debate. Despite its multidimensional structure, it fails to clearly distinguish between sympathy and empathy [11].

A major instrument for measuring basic empathy is the Basic Empathy Scale (BES), which was developed based on the definition of empathy as "understanding and sharing the emotional states and emotional content of others." The BES addresses the limitations of previous empathy scales by avoiding conceptual overlap with related constructs such as sympathy, social desirability, and interpersonal communication skills. It demonstrates strong reliability and validity, and its cross-cultural consistency has been confirmed in countries such as France and Italy. Each item on the BES is rated on a 5-point Likert scale, with higher scores indicating greater agreement with the statement. Domestic research in China has shown that the Basic Empathy Scale meets psychometric reliability standards. It is significantly correlated with the Interpersonal Reactivity Index and the Alexithymia Scale, but not significantly correlated with social desirability, indicating that the BES possesses good reliability and validity.

At present, a number of empathy scales have been developed for different target populations through various empirical studies. In the context of healthcare, researchers have approached empathy primarily from a cognitive perspective, viewing it as the ability to understand patients’ internal experiences and viewpoints. Based on this conceptualization, the Jefferson Scale of Empathy – Health Professionals version (JSE-HP) was developed in 2001 by Dr. Mohammadreza Hojat and his research team at the Center for Research in Medical Education and Health Care, Jefferson University, USA [12]. The scale has demonstrated good reliability and validity. Additionally, the Chinese version of the Jefferson Scale of Empathy, translated and adapted by An Xiuqin and colleagues, has been widely used both domestically and internationally in medical and nursing settings.

In comparison, it is only in recent years that researchers have begun to explore college students’ interpersonal and empathic abilities from the perspective of mental health. Among these efforts, Zhang Xinwei and colleagues developed the College Students' Empathy Scale, which measures empathy across four dimensions: perspective taking, insight, emotional contagion, and emotional detachment. The scale consists of 46 items and has demonstrated good reliability and validity [13].

1.4. Empathy and intimate relationships

1.4.1. Empathy and familial bonds

Familial bonds represent the most fundamental form of intimate relationships, typically existing among members of the same family. Empathy plays a crucial role in familial relationships, particularly between parents and children. Research by Zhang Xianying and others [14] has shown that parental empathy is closely associated with children's emotional development and behavioral outcomes. Parents with high empathic ability are better able to understand and respond to their children's emotional needs, thereby fostering emotional security and enhancing their children's social adaptability [15]. Moreover, empathy also contributes significantly to sibling interactions, helping them to resolve conflicts and build deep emotional connections.

1.4.2. Empathy and romantic love

Romantic love is the central form of adult intimate relationships, in which empathy plays a vital role. Research indicates that partners with higher empathic abilities are better able to understand and respond to each other’s emotional needs, thereby enhancing relationship satisfaction and stability [16]. Empathy facilitates emotional communication and conflict resolution, reducing misunderstandings and disputes. Additionally, empathy is closely linked to trust and attachment within intimate relationships. Individuals with strong empathic abilities are more likely to establish and maintain trusting bonds, which in turn improves the overall quality of romantic relationships.

1.4.3. Empathy and friendship

Friendship is an intimate relationship based on equality and reciprocity, in which empathy also plays an important role[17]. Friends with higher empathic abilities are better able to understand and support each other, thereby deepening and sustaining the friendship. Empathy promotes emotional connection and cooperation between friends, helping them to provide mutual support when facing challenges and difficulties. Moreover, empathy plays a key role in the formation and maintenance of friendships, as individuals with strong empathic abilities are more likely to attract and retain friends, thus forming stable social networks.

1.5. The correlation and influence between empathy and intimate relationships

The correlation between empathy and intimate relationships can be understood from multiple perspectives. First, empathy facilitates emotional understanding and responsiveness, thereby strengthening emotional bonds and the sense of intimacy. Second, empathy promotes trust and attachment, reduces conflicts and misunderstandings, and consequently enhances relationship stability and satisfaction. Finally, empathy is closely linked to individuals’ mental health and social adaptability. Those with higher empathic ability are more likely to establish and maintain healthy intimate relationships, which in turn improves their overall quality of life.

Empathy, as the ability to understand and share the emotions of others, plays a vital role in intimate relationships. Whether in familial bonds, romantic love, or friendship, empathy promotes emotional connection, strengthens trust and attachment, and reduces conflicts and misunderstandings, thereby enhancing the quality and stability of relationships. Based on the above research findings, it is evident that empathy is correlated with different types of intimate relationships; however, previous studies have not integrated these two constructs comprehensively. Therefore, this study aims to develop a questionnaire to investigate whether college students exhibit differences in empathy across various intimate relationship contexts, and to what extent these differences manifest.

2. Participants and methods

2.1. Participants

Sample 1 (Initial Survey): Using convenience sampling, college students from universities across Beijing, Hubei, Shandong, Gansu, Jiangsu, Tianjin, Sichuan, Shaanxi, Anhui, Hainan, Heilongjiang, Yunnan, Hebei, Shanxi, and Chongqing were invited to complete an online questionnaire. A total of 262 questionnaires were distributed, with 152 valid responses collected, resulting in an effective response rate of 58%. The average age of valid participants was 19.96 years. Among them, 26 were male, accounting for 17.11% of the sample, and 126 were female, accounting for 82.89%.

Sample 2 (Formal Survey): Using convenience sampling, college students from universities in Beijing, Hubei, Shandong, Gansu, Shanghai, Tianjin, Anhui, Shaanxi, Hebei, Jiangsu, Liaoning, and Shanxi were invited to complete an online questionnaire. A total of 193 questionnaires were distributed, with 110 valid responses received, yielding an effective response rate of 57%. The average age of participants was 20.65 years. Among them, 32 were male, accounting for 29.09% of the sample, and 78 were female, accounting for 70.91%.

All participants took part in this study voluntarily, having been fully informed and providing their consent.

2.2. Research procedure

2.2.1. Development of the initial questionnaire

By reviewing domestic and international theoretical and empirical studies on empathy, and extensively examining literature on empathy from the past five years—particularly focusing on intimate relationships—we established a framework dividing empathy in intimate relationships into three dimensions: empathy toward family members, friends, and romantic partners. Based on the reviewed literature and existing relevant scales, an initial pool of 60 items was drafted. The questionnaire employed a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “Strongly Disagree,” “Disagree,” “Neutral,” “Agree,” to “Strongly Agree,” scored 1 through 5, respectively. Reverse-coded items were scored inversely. Psychology experts were consulted to evaluate whether the items accurately represented the corresponding dimensions, removing items inconsistent with their intended constructs. They also assessed the rationality and completeness of the scale dimensions, judged the representativeness of each item, and ensured that the wording was suitable for college students’ reading habits. Ultimately, 30 items were retained, including 3 reverse-coded items, forming the initial version of the Empathy Ability Questionnaire in Intimate Relationships among College Students.

2.2.2. Formal administration and analysis procedure

Based on the initial survey results, the questionnaire was revised to form the final version. Following the principles and methods of scale development, the following item analyses were conducted: ①Items with nonsignificant critical ratio (CR) values based on the initial data were deleted. ②Items failing to meet statistical criteria in the exploratory factor analysis of the initial data were removed. Through this process, the finalized Empathy Ability Questionnaire in Intimate Relationships among College Students was developed for formal administration.

2.2.3. Criterion measure

This study used the Toronto Empathy Questionnaire (TEQ) as the criterion measure. The TEQ assesses individuals’ level of empathy and consists of 9 items, including 2 reverse-scored items reflecting high levels of empathy. The scale employs a 5-point scoring system: positively worded items are scored from 1 (“Never”) to 5 (“Always”), while reverse-scored items are scored inversely. Reliability analysis indicated a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.815, demonstrating good reliability and validity. Moreover, the TEQ has been shown to be appropriate for use within the Chinese cultural context.

2.2.4. Statistical methods

Item analysis, reliability and validity testing, and exploratory factor analysis were conducted using SPSS 17.0. Confirmatory factor analysis was performed using AMOS 24.0.

3. Results

3.1. Initial survey analysis

3.1.1. Item analysis

Based on the total questionnaire scores, participants were divided into a high-score group (top 27%) and a low-score group (bottom 27%). Using SPSS, total scores were calculated, and an independent samples t test was conducted. In the initial questionnaire, each group consisted of 41 participants. Analysis revealed that three items had significance values greater than 0.05: “I may feel afraid when a family member asks me for help,” “I may feel afraid when a friend asks me for help,” and “I may feel afraid when a romantic partner asks me for help.” These three items were deleted, while all other items met the statistical criteria and were retained.

3.1.2. Exploratory factor analysis

The data were subjected to the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) test and Bartlett’s test of sphericity to assess suitability for factor analysis. The results indicated a KMO measure of sampling adequacy of 0.822, and Bartlett’s test yielded c² = 2341.747, df = 351, p < 0.001, confirming that the data were appropriate for factor analysis. Principal component analysis was conducted on the remaining 27 items. During the analysis, five items that did not meet statistical criteria were removed, leaving 22 items with factor loadings all exceeding 0.4. The exploratory factor analysis initially identified five factors related to college students’ empathy: Empathy toward Romantic Partners, Empathy toward Friends, Positive Empathy toward Family Members, Situational Empathy, and Negative Empathy toward Family Members (see Table 1 for details). However, attempts to remove the factors of Negative Empathy toward Family Members and Situational Empathy resulted in a decrease in the internal consistency of the questionnaire. Therefore, these two factors were combined for further analysis. Since both Positive and Negative Empathy toward Family Members share the family as their focus, they were merged into a single factor: Empathy toward Family Members, within acceptable statistical parameters. Regarding Situational Empathy, the three items included were: "When I see some romantic tragedies, I imagine how I would feel if it happened to me," "When I see some friendship tragedies, I imagine how I would feel if it happened to me," "When I see some family tragedies, I imagine how I would feel if it happened to me." Analysis suggested that the emergence of this factor may be due to the exploratory factor analysis not constraining the three items to fixed factors. The system grouped these items based on their emphasis on "tragedy" rather than "intimate relationships." Consequently, we decided to reclassify these three items into the factors corresponding to family empathy, friend empathy, and romantic partner empathy. Reliability testing of these three revised factors showed good internal consistency, with Cronbach’s alpha coefficients of 0.808, 0.822, and 0.836, respectively.

|

Factor1 (lovers' empathy) |

Factor2 (friends’ empathy) |

Factor3 (familial positive empathy) |

Factor4 (situational empathy) |

Factor5 (familial negative empathy) |

|||||

|

item |

loading |

item |

loading |

item |

loading |

item |

loading |

item |

loading |

|

Q13 Q10 Q15 Q12 Q11 Q9 |

0.794 0.786 0.757 0.732 0.730 0.717 |

Q8 Q3 Q5 Q7 Q4 Q2 Q6 |

0.772 0.690 0.607 0.598 0.569 0.569 0.519 |

Q16 Q19 Q20 Q17 |

0.866 0.785 0.688 0.543 |

Q14 Q1 Q18 |

0.792 0.790 0.683 |

Q22 Q21 |

0.647 0.572 |

3.1.3. Reliability testing

Statistical analysis showed that the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the initial full questionnaire was 0.892. After deleting eight items that did not meet the criteria in item analysis and exploratory factor analysis, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of the revised questionnaire increased slightly to 0.894. Overall, the Empathy Ability Questionnaire in Intimate Relationships among College Students developed from the initial survey demonstrated good reliability.

3.1.4. Discussion of the initial survey

This study conducted item analysis and exploratory factor analysis on the initial version of the Empathy Ability Questionnaire in Intimate Relationships among College Students. Based on the results, eight items were removed. The analysis initially identified five factors: Empathy toward Romantic Partners, Empathy toward Friends, Positive Empathy toward Family Members, Situational Empathy, and Negative Empathy toward Family Members. According to the results and statistical principles, these were revised into three factors. The internal consistency coefficients (Cronbach’s alpha) for the three factors—Empathy toward Family Members, Empathy toward Friends, and Empathy toward Romantic Partners—were 0.808, 0.822, and 0.836, respectively. This structure essentially fits the conceptual model of empathy across the three types of intimate relationships.

3.2. Formal survey analysis

3.2.1. Item analysis

Based on total scores, participants were divided into a high-score group (top 27%) and a low-score group (bottom 27%). Using SPSS, total scores were calculated, followed by an independent samples t test. In the formal questionnaire, each group included 30 participants. Analysis showed that the significance levels of all items were less than 0.05, with the high-score group having higher mean scores than the low-score group. Additionally, each item’s score was significantly correlated with the total score.

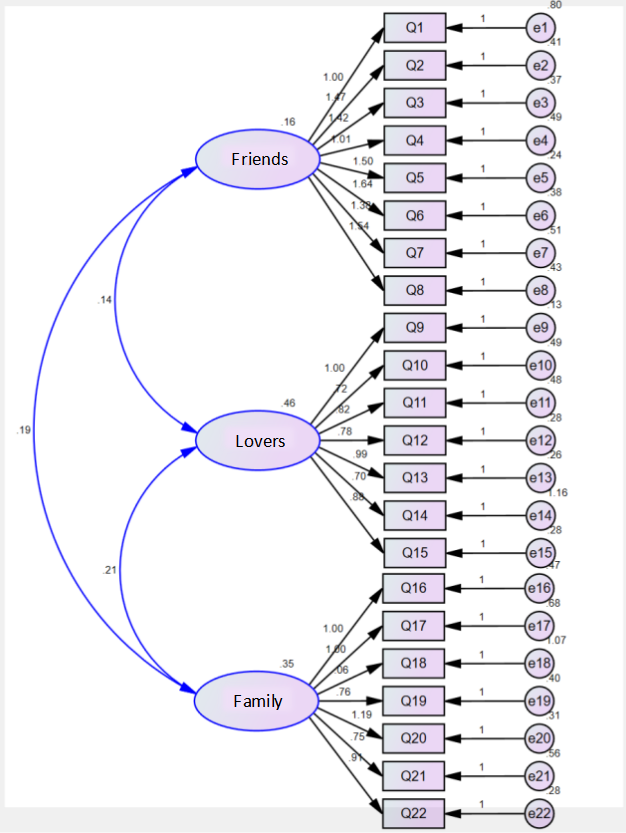

3.2.2. Confirmatory factor analysis (construct validity)

Confirmatory factor analysis was conducted on the formal questionnaire data to verify the construct validity of the Empathy Ability Questionnaire in Intimate Relationships among College Students. The results indicated that the three-factor model demonstrated an acceptable fit: x²/df = 2.09, GFI = 0.75, AGFI = 0.69, NFI = 0.67, CFI = 0.79, IFI = 0.79, and RMSEA = 0.10 (see Figure 1 for details).

3.2.3. Reliability testing

Statistical analysis showed that the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the formal questionnaire was 0.896, and the split-half reliability was 0.918. Overall, the Empathy Ability Questionnaire in Intimate Relationships among College Students demonstrated good reliability in the formal administration.

3.2.4. Validity testing

This study used the Toronto Empathy Questionnaire as the criterion measure for validity analysis. The questionnaire contains 9 items. Statistical analysis showed that the total score of the present scale was significantly correlated with the total score of the Toronto Empathy Questionnaire, with a correlation coefficient of 0.714 (p < 0.001), indicating good criterion validity for this scale.

3.2.5. Differences in empathy toward family members, friends, and romantic partners

A repeated measures ANOVA was conducted on empathy scores for family members, friends, and romantic partners. The results indicated a significant difference in college students’ empathy across these three types of intimate relationships, F(2, 108) = 39.042, p < 0.001. Further multiple comparison analyses revealed that empathy toward family members (26.12 ± 3.87 SE) was significantly lower than empathy toward friends (29.65 ± 4.79 SE; p < 0.001, Bonferroni correction) and empathy toward romantic partners (27.93 ± 4.40 SE; p < 0.001, Bonferroni correction). Additionally, empathy toward friends was significantly higher than empathy toward romantic partners (p < 0.001, Bonferroni correction).

Next, gender differences were examined for the total empathy score as well as for empathy toward family members, friends, and romantic partners. The results showed that males’ overall empathy ability (83.56 ± 8.42 SE) was significantly lower than that of females (83.74 ± 11.85 SE; t = –0.090, p = 0.049, independent samples t test). However, no significant gender differences were observed within the three types of intimate relationships (p > 0.05, independent samples t test).

3.2.6. Discussion of the formal survey

This study conducted item analysis and reliability and validity testing on the formal administration of the Empathy Ability Questionnaire in Intimate Relationships among College Students. Based on the analysis, all 22 items were retained. Difference analyses revealed that college students exhibited the highest empathy ability in friendships, followed by romantic relationships, and the lowest in familial relationships. Significant gender differences were found in overall empathy ability; however, no significant gender differences were observed within the specific types of intimate relationships. Using the Toronto Empathy Questionnaire (TEQ) as the criterion measure, the present scale showed a significant correlation with the TEQ, indicating good criterion validity.

4. Analysis and discussion

4.1. General discussion

Based on the data analysis, we conclude that contemporary college students exhibit significant differences in empathy across three distinct dimensions of intimate relationships. Their empathy ability toward friends is higher than that toward romantic partners and family members, while empathy toward romantic partners is higher than that toward family members. Thus, it can be concluded that college students demonstrate the highest level of empathy within friendships and the lowest within familial relationships.

Regarding gender, significant differences were also found. Consistent with previous studies, females demonstrated significantly higher overall empathy ability than males. However, no significant gender differences were observed across the three specific dimensions.

4.2. Limitations and shortcomings

Although this questionnaire has yielded certain results, limitations in resources such as capability and time have led to several deficiencies in the current version. Future research should focus on continuously improving these shortcomings by enhancing research capacity and rigor, thereby making the questionnaire more comprehensive and robust.

Regarding participant sampling, due to limitations in manpower and time, although data were collected from college students across most provinces and cities in China, a large proportion of the data came from students at a certain sports university in Beijing. The questionnaire’s effective response rate was relatively low, and the sample cannot be considered fully representative of the broader college student population. Additionally, there was a large gender imbalance, which may have reduced the external validity of the study and led to insufficient evidence for some inferences. There was also a considerable difference in the number of participants between the initial and formal surveys, with fewer participants in the formal survey, which may have influenced the results. Therefore, future research should expand the sample size and scope to include a larger and more representative participant pool, thereby enhancing the scientific rigor of the study. Furthermore, participants without any romantic relationship experience were excluded during the selection process. As a result, this study cannot explore whether, or to what extent, empathy ability differs for such individuals when facing family and friendship relationships.

Regarding data analysis, due to time constraints, test-retest reliability analysis was not conducted. Therefore, the data analysis results require further refinement and completion in future research.

4.3. Innovations and prospects

This study situates college students’ empathy ability within the context of intimate relationships, exploring whether and to what extent their empathy differs when facing different types of intimate relationship partners. The developed questionnaire may provide future research on intimate relationships with additional variables and possibilities. If gender balance is achieved in future samples, it may be possible to more accurately measure gender differences in empathy ability within intimate relationships.

5. Conclusions

(1) The Empathy Ability Questionnaire in Intimate Relationships among College Students consists of 22 items and is composed of three dimensions.

(2) The questionnaire demonstrates sound theoretical construction and good reliability and validity indices, making it an effective tool for studying empathy ability in college students’ intimate relationships.

(3)Females exhibit significantly higher empathy ability than males. Significant differences in empathy ability were found across the three dimensions of family, friendship, and romantic relationships, with college students showing the highest empathy level in friendships and the lowest in familial relationships.

References

[1]. Hoffman, M. L. (1975). Developmental synthesis of affect and cognition and its implications for altruistic motivation. Developmental Psychology, 11(5), 607–622.

[2]. Batson, C. D., Chang, J., Orr, R., & Rowland, J. (2002). Empathy, attitudes, and action: Can feeling for a member of a stigmatized group motivate one to help the group? Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 28(12), 1656–1666.

[3]. De Vignemont, F., & Singer, T. (2006). The empathic brain: How, when and why? Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 10(10), 435–441.

[4]. Singer, T. (2006). The neuronal basis and ontogeny of empathy and mind reading: Review of literature and implications for future research. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 30(6), 855–863.

[5]. Piaget, J., & Inhelder, B. (1970). The gaps in empiricism. Springer Study Edition, 24–35.

[6]. Zhang, L. L. (2014). Investigation of empathy ability among preschool teachers [Master’s thesis, Nanjing Normal University].

[7]. Collins, W. A., Welsh, D. P., & Furman, W. (2009). Adolescent romantic relationships. Annual Review of Psychology, 60, 631–652.

[8]. Kirchler, E., Rodler, C., & Hoezl, E., et al. (2001). Conflict and decision-making in close relationships: Love, money, and daily routines. Hove, East Sussex: Psychology Press, 39–47.

[9]. Yang, X. (2023). The influence of intimate relationships on empathy processes [Master’s thesis, Central China Normal University].

[10]. Chen, Y. X. (2021). Gender differences in the influence of intimate relationships on emotional and cognitive empathy [Master’s thesis, Soochow University].

[11]. Simon, B. C., & Sally, W. (2004). The Empathy Quotient: An investigation of adults with Asperger syndrome or high functioning autism, and normal sex differences. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 34, 164–175.

[12]. Hojat, M., Mangione, S., Nasca, T. J., Cohen, M. J. M., Gonnella, J. S., Erdmann, J. B., Veloski, J. J., & Magee, M. (2001). The Jefferson Scale of Empathy: Development and preliminary psychometric data. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 61, 349–365.

[13]. Zhang, X. W., Zhong, Z. L., & Zhou, P. (2017). Development and psychometric testing of the college student empathy scale. Advances in Psychological Science, 27(10), 1214–1222.

[14]. Zhang, X. Y., & Zhu, L. F. (2016). Research progress on peer acceptance, empathy, and parenting styles. Popular Science & Technology, (12), 112–114.

[15]. Yang, J., Zhang, X. H., Zhao, X. L., & He, Y. (2020). Childhood emotional neglect as a predictor of college students’ empathy ability. Community Psychology Research, (1), 143–160.

[16]. Yu, D. Y. (2022). The influence of romantic love on empathy and its gender differences: Based on cross-sectional and longitudinal studies [Master’s thesis, Southwest University].

[17]. Zhang, K., Fang, X. H., & Li, Z. W. (2023). The relationship between loneliness and aggressive behavior in college students: The chain mediation of empathy and interpersonal trust. Journal of Huaibei Normal University (Philosophy and Social Sciences Edition), (6), 117–123.

Cite this article

Zhang,R.;Wang,Z.;Jin,X.;Ou,L.;Li,Y. (2025). Development of the Empathy Ability Questionnaire in Intimate Relationships among College Students. Lecture Notes in Education Psychology and Public Media,98,9-20.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Education Innovation and Psychological Insights

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Hoffman, M. L. (1975). Developmental synthesis of affect and cognition and its implications for altruistic motivation. Developmental Psychology, 11(5), 607–622.

[2]. Batson, C. D., Chang, J., Orr, R., & Rowland, J. (2002). Empathy, attitudes, and action: Can feeling for a member of a stigmatized group motivate one to help the group? Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 28(12), 1656–1666.

[3]. De Vignemont, F., & Singer, T. (2006). The empathic brain: How, when and why? Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 10(10), 435–441.

[4]. Singer, T. (2006). The neuronal basis and ontogeny of empathy and mind reading: Review of literature and implications for future research. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 30(6), 855–863.

[5]. Piaget, J., & Inhelder, B. (1970). The gaps in empiricism. Springer Study Edition, 24–35.

[6]. Zhang, L. L. (2014). Investigation of empathy ability among preschool teachers [Master’s thesis, Nanjing Normal University].

[7]. Collins, W. A., Welsh, D. P., & Furman, W. (2009). Adolescent romantic relationships. Annual Review of Psychology, 60, 631–652.

[8]. Kirchler, E., Rodler, C., & Hoezl, E., et al. (2001). Conflict and decision-making in close relationships: Love, money, and daily routines. Hove, East Sussex: Psychology Press, 39–47.

[9]. Yang, X. (2023). The influence of intimate relationships on empathy processes [Master’s thesis, Central China Normal University].

[10]. Chen, Y. X. (2021). Gender differences in the influence of intimate relationships on emotional and cognitive empathy [Master’s thesis, Soochow University].

[11]. Simon, B. C., & Sally, W. (2004). The Empathy Quotient: An investigation of adults with Asperger syndrome or high functioning autism, and normal sex differences. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 34, 164–175.

[12]. Hojat, M., Mangione, S., Nasca, T. J., Cohen, M. J. M., Gonnella, J. S., Erdmann, J. B., Veloski, J. J., & Magee, M. (2001). The Jefferson Scale of Empathy: Development and preliminary psychometric data. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 61, 349–365.

[13]. Zhang, X. W., Zhong, Z. L., & Zhou, P. (2017). Development and psychometric testing of the college student empathy scale. Advances in Psychological Science, 27(10), 1214–1222.

[14]. Zhang, X. Y., & Zhu, L. F. (2016). Research progress on peer acceptance, empathy, and parenting styles. Popular Science & Technology, (12), 112–114.

[15]. Yang, J., Zhang, X. H., Zhao, X. L., & He, Y. (2020). Childhood emotional neglect as a predictor of college students’ empathy ability. Community Psychology Research, (1), 143–160.

[16]. Yu, D. Y. (2022). The influence of romantic love on empathy and its gender differences: Based on cross-sectional and longitudinal studies [Master’s thesis, Southwest University].

[17]. Zhang, K., Fang, X. H., & Li, Z. W. (2023). The relationship between loneliness and aggressive behavior in college students: The chain mediation of empathy and interpersonal trust. Journal of Huaibei Normal University (Philosophy and Social Sciences Edition), (6), 117–123.