1. Introduction

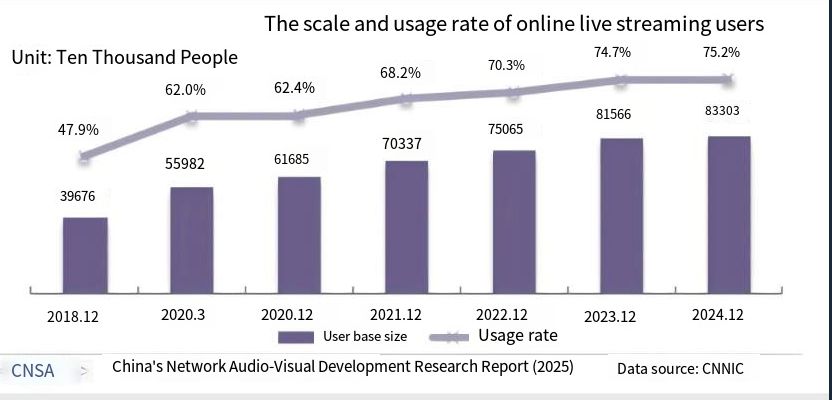

As a typical form of the digital economy, the live streaming industry in China has undergone a complete development cycle—from its emergence as PC-based show-style streaming around 2005, through phases of “technology-driven model innovation,” to widespread social penetration. According to the 55th Statistical Report on Internet Development in China released by the China Internet Network Information Center, as of December 2024, the number of live streaming users in China had reached 833 million, accounting for 75.2% of all internet users (see Figure 1). In 2023, the industry's market size exceeded 4.9 trillion yuan, with live-streaming e-commerce accounting for 9.8% of the total retail sales of consumer goods [1]. While live streaming has generated significant economic and social value—such as alleviating employment pressure by creating numerous job opportunities, stimulating consumption vitality through product promotion, and fostering cultural exchange by overcoming spatial and temporal constraints, thereby giving rise to new formats like “livestreaming to support agriculture” and “online education”—it has also introduced numerous governance challenges. These include false advertising, irrational tipping by minors, and legal disputes over the status of virtual streamers. The industry thus presents a core contradiction: the coexistence of “technology-driven innovation and regulatory challenges.” In response, legal regulation has followed an evolutionary path characterized by “delayed response—dynamic adjustment—systematic construction.” Since the promulgation of the Administrative Provisions on Internet Live Streaming Services in 2016, which established platform responsibilities, to the issuance of joint regulatory documents by seven central departments in 2023, a multi-level governance framework has gradually taken shape. This framework consists of legal statutes, administrative regulations, departmental rules, and industry standards. This paper aims to explore, from the perspective of legal sociology, the collaborative development and mutual refinement between legal regulation and the live streaming industry.

2. Development trajectory and stage characteristics of the live streaming industry

2.1. Technology-driven nascent stage (2005–2014): from technical experimentation to commercial prototype

This stage was dominated by PC-based show-style live streaming, with representative platforms including YY Live and 6.cn. The core functionality of these platforms was limited to unidirectional entertainment-oriented interaction. Given that the user base numbered only in the tens of millions, the industry’s societal impact remained confined to niche entertainment communities. Legal regulation during this period was essentially absent, characterized by a lack of dedicated legislation and reliance on the general provisions of the Administrative Measures on Internet Information Services. A typical phenomenon was the dominance of platform self-regulation as the primary governance tool. For example, in 2012, YY Live introduced its Code of Conduct for Streamers, yet this lacked any binding legal authority [2].

2.2. Mobile internet expansion period (2015–2018): from consumption upgrade to social phenomenon

The widespread adoption of 4G networks and the smartphone boom triggered an explosive growth in the live streaming industry. Platforms such as Douyin and Kuaishou gradually reshaped user habits with their “short video + live streaming” hybrid model. Live streaming content diversified from the original single-focus entertainment to a multifaceted mix of “entertainment + e-commerce + education.” The industry’s economic scale grew exponentially: by 2018, the live streaming e-commerce market reached 354.5 billion yuan, with Taobao Live alone surpassing 100 billion yuan in revenue. However, this rapid expansion was accompanied by a governance vacuum, with industry irregularities becoming increasingly prominent. According to the 2018 CCTV 3.15 Consumer Rights Day special report, numerous egregious incidents were exposed, including streamers selling counterfeit and substandard goods through “beauty filters + scripted pitches,” minors spending exorbitant amounts on gifts, and the proliferation of vulgar content in live broadcasts.

In 2016, the Cyberspace Administration of China promulgated the Administrative Provisions on Internet Live Streaming Services, which for the first time explicitly established three core regulatory requirements: platform qualification review, streamer real-name authentication, and real-time content monitoring. It also introduced a “license-before-permit” access mechanism, stipulating that obtaining the Network Culture Operation Permit was a prerequisite for engaging in online live streaming activities. However, regulatory measures remained primarily administrative in nature, and the provisions concerning legal liability consisted of only 11 articles. Detailed rules addressing emerging and difficult-to-prove issues, such as false advertising and data fabrication, were still lacking, resulting in a pronounced feature of “catch-up regulation.”

2.3. Period of digital governance and standardization (2019–present): from unregulated growth to ecological reconstruction

The commercialization of 5G and the widespread adoption of AI technologies have jointly driven a transformation in the industry’s ecosystem. By 2023, the live streaming e-commerce market size reached 4.9 trillion yuan, with over 30,000 Multi-Channel Network (MCN) agencies—companies that assist contracted influencers in continuous content production and monetization—and the number of virtual streamers exceeded 100,000. However, these technological applications have introduced new challenges [3]. Regulation has entered a stage of “precision governance,” characterized as follows:

(1) Systematic Institutional Provision: In 2023, seven government departments jointly issued the Guiding Opinions on Strengthening the Normative Management of Online Live Streaming, establishing twelve mechanisms including “account tiered management,” “reward limits,” and “special commissioners for the protection of minors.”

(2) More Refined and Professional Responsibility Allocation: The Code of Conduct for Online Streamers explicitly stipulates 31 prohibitive rules and requires streamers in specialized fields such as healthcare and education to hold relevant professional certifications (e.g., medical licenses, teaching certificates).

(3) Deep Integration of Technological Governance: Pilot programs for “AI content review systems” were launched in Beijing and Shanghai, mandating platforms to establish mechanisms that achieve a content violation interception rate of over 95%.

(4) Social Impact Exhibiting a Double-Edged Sword Effect: Positive examples include the 2023 “Dongfang Zhenxuan” agricultural support live streaming campaign, which significantly boosted agricultural product sales in Shaanxi Province. Conversely, negative cases such as the “Xiao Yang Ge” livestream room investigation by the State Administration for Market Regulation for price fraud highlight the dynamic and ongoing contest between governance systems and industry development.

3. Evolution of legal regulation and core issues

3.1. Content governance: from crude control to technically adapted, refined regulation

(1) Iteration and Coordination of Legal Rules

Foundational Phase (2016–2020): Relying on the superior legal framework of the Cybersecurity Law and the E-Commerce Law, regulation expanded the supervisory chain through the Administrative Measures on Internet Live Streaming Services. However, governance was primarily based on “manual review plus user complaints.” In 2018 alone, over one million live streaming-related complaints were filed, highlighting low processing efficiency.

Targeted Breakthrough (2021–2022): The Interim Measures for the Administration of Live Streaming Marketing explicitly established a “negative list” for live streaming marketing participants, prohibiting behaviors such as deleting consumer reviews. The Code of Conduct for Online Streamers incorporated virtual streamers under regulation, requiring clear labeling of “AI-generated” content. The 2023 Interim Measures for the Administration of Generative Artificial Intelligence Services further refined these requirements, with violations subject to fines up to 1 million yuan.

Coordinated Deepening (2023–Present): The regulatory model has shifted toward “AI-based review supplemented by manual verification,” integrated with local normative frameworks such as Hangzhou’s “Compliance Guidelines Database,” covering the entire content process [4].

(2) Shift in Regulatory Focus

In the early stage, emphasis was placed on industry development efficiency, with content violations generally addressed through “rectification within a limited timeframe.” After 2021, the focus shifted toward fairness and rights protection, clarifying boundaries through landmark cases. For example, in 2022, the “Beauty Influencer Filter Case” established the standard that “reasonable beautification (such as skin tone adjustment) does not constitute fraud, whereas altering the product’s demonstrated effects (such as modifying facial contours) constitutes false advertising.”

(3) Proactive Technological Regulation

The approach evolved from passively responding to technological issues (e.g., controversies over beauty filters) to proactively preventing risks. This involves both prohibiting the misuse of technology (such as failure to label AI-generated content) and encouraging technology-enabled supervision (such as AI-powered real-time review of prohibited content).

3.2. Subject responsibility: from ambiguous allocation to a precisely defined rights and obligations system

(1) Legal Rules Refining Responsibility

Platform Responsibility: The shift has been from the “safe harbor principle” (limited to the obligation to notify and remove content) toward an “active supervision duty.” The 2023 Guiding Opinions require the establishment of “streamer credit files,” with permanent bans imposed on those who violate regulations three times. In the Li Jiaqi Team False Advertising Case, platforms were required to assist in evidence collection, and the violating party (an MCN agency) was fined five times their sales revenue.

Streamer Responsibility: Distinctions have been made between “professional streamers” and “amateur streamers,” clarifying their respective obligations. Criminal liability has been strengthened [5]. In 2023, the “Liangshan Qubu” case marked the first criminal precedent in the live streaming sector, where a streamer was sentenced to two years’ imprisonment and fined 500,000 yuan for selling substandard honey using fabricated poverty alleviation scenes, convicted of false advertising.

(2) Fairness-Oriented Shift in Regulatory Focus

In the early stage, responsibility allocation was vague and primarily aimed at protecting platform development. In later stages, emphasis shifted toward “equivalence of rights and responsibilities,” requiring each link in the chain—platforms, MCN agencies, and streamers—to bear corresponding liability. For example, platforms failing to fulfill product selection review obligations are held jointly liable, while professional streamers, due to their expertise, bear a higher standard of care.

(3) Responsibility Binding through Technological Application

Technology has empowered the enforcement of responsibility. For instance, platforms utilize technical systems such as “streamer credit files” to trace violations. Operators of virtual streamers are required to assume the same legal responsibilities as real-person streamers, directly linking technological use with legal accountability.

3.3. Protection of rights and interests: from single-dimensional to comprehensive full-chain safeguarding network

(1) Systematic Construction of Legal Rules

Protection of Minors: A mechanism of “prevention before the fact — monitoring during the process — remedy after the fact” has been established. The 2024 Regulations on the Protection of Minors Online prohibit minors from live streaming tips and require platforms to implement “facial recognition + consumption limits” (a daily limit of 50 yuan). A 2023 Supreme People’s Court case clarified that platforms failing to fulfill their interception obligations must bear over 70% of the compensation liability.

Consumer Rights: The Administrative Measures for Live Streaming Marketing break the convention of “no returns or exchanges for flash sale items,” explicitly granting a seven-day no-reason return policy for discounted products. The General Administration of Customs has established a “cross-border live streaming goods traceability code” system (see Figure 2), enabling full-chain traceability from “overseas procurement — logistics transportation — domestic sales.”

(2) Value Shift in Regulatory Focus

In the early stage, emphasis was placed on industry expansion, with insufficient coverage of rights protection in areas such as after-sales service and cross-border transactions. Since 2021, the focus has shifted toward fairness and protection, addressing loopholes like “difficulties in after-sales service” and “information asymmetry” through departmental regulations and local cooperation—for example, Shanghai mandates a 100% tax declaration rate for streamers.

(3) Technological Empowerment of Rights Protection

The approach evolved from passively accepting rights risks caused by technology (such as irrational tipping by minors) to proactively leveraging technology to enhance protection. Measures include facial recognition systems to restrict minors’ tipping and traceability code technologies to ensure product authenticity, thus achieving a dual safeguard of “technological prevention and legal remedy.”

4. Analysis of the legal-sociological mechanism of interaction between law and the live streaming industry

The interaction between law and the live streaming industry essentially reflects a dynamic adaptation between institutional supply and social demand. Within the framework of legal sociology, this interaction manifests three major logics: instrumental control, anti-formalistic adjustment, and pluralistic co-governance. These logics demonstrate the legal system’s adaptive response to technological innovation and changes in social structure.

4.1. Instrumentalist perspective: law as an institutional tool of social control

Law guides the development direction of the live streaming industry through rule-making, functioning as a directive force. Within this process, a governance chain of “institutional framework — behavioral adjustment” is formed:

Structural regulation reshapes the industry ecosystem. Through admission systems (dual-license approval, streamer real-name authentication), compliance thresholds are raised, thereby driving industry resources to concentrate in leading platforms. In 2024, the number of newly approved platforms declined by 43% year-on-year, and market concentration increased significantly. To address the distortion of the “reward economy,” a tiered limit system was established, prompting the income structure to shift from reliance on user tipping toward diversified profit models. By 2024, tipping income accounted for 35%, reconstructing the commercial logic of the live streaming industry.

Institutional risk hedging of technological risks. In response to risks such as identity fraud and content falsification caused by AI technology, the law constructs a system of “prohibitive norms + preventive measures”: virtual streamers are required to be labeled as “AI-generated,” with violations subject to fines up to 1 million yuan, thereby curbing the misuse of technology; simultaneously, a technology application filing system is established to evaluate the effects of technologies like digital beautification that may affect perception, balancing technological innovation and social risk to avoid value distortions caused by excessive technological intervention.

Pluralistic allocation of interests and rights. In the field of user rights protection, the law constructs a fair trading order through responsibility allocation: regarding tipping by minors, a dual mechanism of “technical interception + legal accountability” is established, holding platforms liable for over 70% of compensation if they fail to fulfill their obligations; in consumer rights protection, joint liability of platforms for streamer qualifications and product quality is clarified, incorporating live-streaming e-commerce into the scope of the Consumer Rights Protection Law, addressing difficulties in subject tracing and promoting a shift in the industry from traffic competition to value competition.

4.2. Anti-formalism perspective: rule evolution driven by industry practice

The development of legal rules originates from social realities and changes with shifts in social forms, rather than being immutable laws. This dynamic adjustment is realized through three pathways:

Judicial practice fills rule vacuums. When emerging business formats exceed the scope of existing legal frameworks, new rules are generated through judicial interpretation in individual cases [6]. For example, in the virtual streamer “persona behind” dispute, the court broke the shackles of traditional rights classification and identified the virtual image as a “personality interest with property attributes,” establishing rights division rules between developers and performers. While providing a judicial paradigm for similar cases, this also reflects the judiciary’s response to rights reconstruction driven by technological innovation.

Technological iteration forces institutional supply. Applications of technologies such as blockchain and NFTs expose legal lag, driving rules to shift from “ex post regulation” to “ex ante adaptation.” In an NFT transaction case, the Hangzhou Internet Court recognized the evidentiary effect of blockchain and established the rule of “automatic performance of smart contracts,” prompting the Digital Economy Promotion Law to incorporate blockchain as a means of data ownership confirmation. This legal breakthrough demonstrates the positive driving force of technological progress on legal systems.

Interest games drive rule reconstruction. Conflicts over power distribution within the industry (such as revenue-sharing disputes between platforms and streamers) lead to governance consensus through negotiation. After protests from small- and medium-sized streamers over the 60% commission taken by top streamers, industry associations issued revenue-sharing guidelines and promoted the inclusion of streamers in new employment protections. This not only broke the one-way model of “government legislation—social enforcement” but also formed a collaborative transformation path of “industry autonomy—legal confirmation.”

5. Conclusion

The governance practice of the live streaming industry has always been accompanied by the interaction and collaboration of multiple actors. This process itself exemplifies the typical pattern of institutional evolution in the digital economy. From a pluralistic perspective, the generative logic of its governance framework is clearly visible: through vertical linkage of central coordination and local innovation, horizontal collaboration between government regulation and industry autonomy, the three-dimensional integration of technological governance and social supervision, and even the bidirectional alignment of domestic rules and international governance, an elastic governance network adapted to industry characteristics is gradually constructed. This process is neither purely government-led nor entirely market-autonomous, but rather a dynamic adaptation of the legal system to the industry’s features of “technological decentralization, pluralistic actors, and global influence.” It not only validates the fundamental proposition in legal sociology that “social change drives institutional innovation,” but also offers a Chinese solution of “pluralistic co-governance” for digital economy governance.

However, the current governance system still faces three core challenges: first, the tension between legal lag and technological innovation persists, with emerging issues such as the legal status of virtual streamers and metaverse asset confirmation lacking specialized regulations, resulting in rule supply failing to keep pace with technological iteration; second, the refinement of regulatory coordination needs improvement, as overlapping responsibilities among multiple departments cause discrepancies in law enforcement standards and high compliance costs for small and medium-sized enterprises, restricting the release of governance effectiveness; third, governance tools for emerging technological risks remain insufficient, with inadequate anticipatory mechanisms and full-chain regulatory capacity for potential risks brought by AIGC-generated content and deep synthesis technologies [7].

Future governance deepening requires a dual-track approach: at the level of rule supply, it is necessary to balance “bottom-line thinking and innovation tolerance,” reserving institutional flexibility for emerging fields such as AIGC and the metaverse, both consolidating bottom lines like data security and rights protection while avoiding excessive regulation that stifles technological innovation; at the level of governance practice, further strengthening the organic linkage of “legal regulation—technological empowerment—social co-governance” is required, releasing the collaborative effectiveness of multiple actors through unified law enforcement standards, reduced compliance costs, and improved social supervision channels; at the level of global governance, promoting the deep integration of China’s experience with international rules is essential, contributing solutions in areas such as cross-border live streaming regulation and digital asset confirmation, thereby enhancing China’s discourse power in digital economy governance. Only in this way can the live streaming industry and legal regulation achieve sustained synergistic evolution, laying a solid institutional foundation for healthy development in the digital era.

References

[1]. Li, T. (2025). Analysis and governance paths of irregularities in live streaming. China Price Regulation and Antitrust, (3), 78–82.

[2]. Zeng, Y. (2017). Characteristics and development trends of live streaming. Journal of Social Sciences, Harbin Normal University, 8(2), 158–161.

[3]. Lin, M. Z. (2025). Legal regulation of consumer rights protection in live streaming marketing. Journal of Journalism Research, 16(6), 226–230.

[4]. Li, J. Y. (2024). Administrative regulation of live streaming marketing in China (Master’s thesis). Shandong Normal University.

[5]. Sun, Z. X., & Qian, Q. (2022). Deviance and regulation: Study on irregularities and governance paths in live streaming. Journal of Hebei Police Vocational College, 22(4), 29–32.

[6]. Zhang, D. R. (2024). Legal status identification and responsibility determination of streamers in live commerce: A case study of the contract dispute between Zheng and Liu (Master’s thesis). Guizhou Normal University.

[7]. Liu, J. X. (2017). On the breakthrough path of “last mile” in live streaming regulation. Modern Audio-Visual, (3), 25–28.

Cite this article

Fu,Y. (2025). The Rise of the Live Streaming Industry and the Evolution of Relevant Legal Regulations. Lecture Notes in Education Psychology and Public Media,103,47-54.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on International Law and Legal Policy

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Li, T. (2025). Analysis and governance paths of irregularities in live streaming. China Price Regulation and Antitrust, (3), 78–82.

[2]. Zeng, Y. (2017). Characteristics and development trends of live streaming. Journal of Social Sciences, Harbin Normal University, 8(2), 158–161.

[3]. Lin, M. Z. (2025). Legal regulation of consumer rights protection in live streaming marketing. Journal of Journalism Research, 16(6), 226–230.

[4]. Li, J. Y. (2024). Administrative regulation of live streaming marketing in China (Master’s thesis). Shandong Normal University.

[5]. Sun, Z. X., & Qian, Q. (2022). Deviance and regulation: Study on irregularities and governance paths in live streaming. Journal of Hebei Police Vocational College, 22(4), 29–32.

[6]. Zhang, D. R. (2024). Legal status identification and responsibility determination of streamers in live commerce: A case study of the contract dispute between Zheng and Liu (Master’s thesis). Guizhou Normal University.

[7]. Liu, J. X. (2017). On the breakthrough path of “last mile” in live streaming regulation. Modern Audio-Visual, (3), 25–28.