1. Introduction

With the gradual proliferation of social media, digital communication’s popularity has been boosted to another level, since “online chatting forum was not introduced in China until 1994” [1]. Visual tools like stickers were integral to online interaction as they are unlike emoji, which are standardized pictograms, stickers are culturally nuanced and platform specific. Moreover, some stickers are tied to trending memes or even branded content. In fact, for 1.3 million users of WeChat (which is 80% of the total Chinese population), around 389 million stickers were exchanged every day [2]. These visuals serve more than mere embellishments since they drive expression, emotional nuance on the basis of an intergenerational dialogue [3]. Despite the ubiquity, the focus on emojis is disproportionately larger in the field of study and thus leaving sticker-related investigation, particularly across age evaluations, under-explored. This gap limits the wholesome understanding in the evolution of digital in response to generational preferences and platform mechanics.

It has been highlighted in existing studies that there does exist an age-related disparity in emoji usage, with younger users adopting more innovative forms (including creating their own, adapting from memes, personal jokes between friends), while older cohorts have preference for more functional or emotional purpose-based stickers. For instance, viral stickers campaigns on DouYin often leverage regional slang, appealing to Gen Z, whereas WeChat’s “Family Moments” stickers cater to middle-aged through familial motifs. Such trends trigger critical questions — Do different age groups use stickers for different communicative purposes? How do platform algorithms and peer networks shape sticker visibility? What implication does this hold for cross-generational digital literacy?

This study addresses all these mentioned questions through three objectives. Firstly, it analyzes variations in sticker usage frequency and purposes across five age groups (0-18, 19-25, 26-40, 41-60, 60+). Secondly, investigation on how social media platforms influence sticker discovery and adoption, comparing algorithmic recommendations (WeChat’s “searching”, DouYin’s “for you”) and organic peer sharing (through friends’ group chats). Thirdly, it gives general categorization to stickers based on semantic function (emotional, humorous, social bonding, cultural, branded) and content structure (facial, object-based, text-dependent) to decode generational preferences.

2. Literature review

While emoji — standardized pictograms — have been extensively studied due to its early invention in the 1980s [4], stickers (culturally nuanced, platform-specific visuals) are, however, under-investigated despite their growing dominance in major social platforms in China. Existing scholarship highlights generational disparities in graphic language (emoji & stickers) adoption, with younger users favoring innovation (creating their own stickers, based memes and jokes) and older users prioritize functionality [5]. This focus on emoji, on the other hand, neglects stickers’ unique role specifically being cultural-based and generational-dividing, particularly in China.

The knowledge of sticker diffusion mechanisms is sparse in particular, yet it would be applied in various practical fields if feasible. Algorithmic recommendations can be applied to social media strategies and that peer-driven sharing in group chats, for instance, can serve a critical method to sticker adoption [6], but the interplay with age-specific preferences remains comparatively covert. Studies on digital slang and memes (similar to stickers) suggest platform algorithms amplify youth-driven trends [7], potentially marginalizing older users who rely on passive exposure. This aligns with media ecology theory [8], which posits that discourse tools reshape social dynamics which is a lens rarely applied to sticker usage.

Theoretical gaps persist in categorizing stickers by purpose (emotional, humorous, social bonding, cultural, branded) and content (facial, object-based, text-dependent). While Herring and Dainas [9] classify emojis by semantic function, stickers’ hybrid nature (e.g., branded content, cultural references) demands a tailored framework. Additionally, existing studies on Chinese digital behavior focus narrowly on youth [10], overlooking cross-generational engagement. This study addresses these gaps by examining sticker usage across five age groups (0-18, 19-25, 26-40, 41-60, 60+), analyzing age-preference correlation, and helps create a categorization system to decode generational preferences.

This research is based on media ecology theory, positing that communication tools reshape social discourse patterns. Through examination on stickers as an innovation in linguistics, this study will contribute to debates on digital language evolution while offering practical strategies designing inclusive platform design. For social media marketers, findings clarify on aligning branded-stickers with age-specific humor or cultural codes, while for policymakers, they can apply the results on regulating sticker content without stifling creativity. Ultimately, this work advances understanding of how generational divides manifest in Chinese rapid digitalized society.

3. Methodology

The study employs a sequential integrated quantitative survey to explore sticker usage across five age cohorts in China. Data collection occurs in the three phases: 1. A pilot survey refining categorization frameworks; 2. A primary survey (n > 300, 50+ per age group); 3. Data analysis and visualization with pie charts, bar charts, and scatter plots.

3.1. Survey design

The survey, distributed via WeChat, Weibo, RED Note, and DouYin, comprises of four sections:

1. Demographics: age, gender, weekly social media usage hours.

2. Usage Patterns: frequency of sticker use, primary platforms, and context.

3. Sticker Preferences: Participants rank their preferred and commonly used sticker types that are categorized from different perspectives.

4. Adoption Drivers: Multiple choice questions on discovery methods, rated by influence.

3.2. Sampling

A stratified sampling strategy ensures even representation across ages and platforms. Quotas are enforced as well using screening questions, with targeted social media recruitment and partnership with elder communities who tend to communicate among themselves mostly. To mitigate self-reporting bias, scenario-based questions are given, as well as clarifications on sticker definitions, and a cohesive and comprehensive series of questions, anchoring responses in concrete behaviors [11].

4. Findings

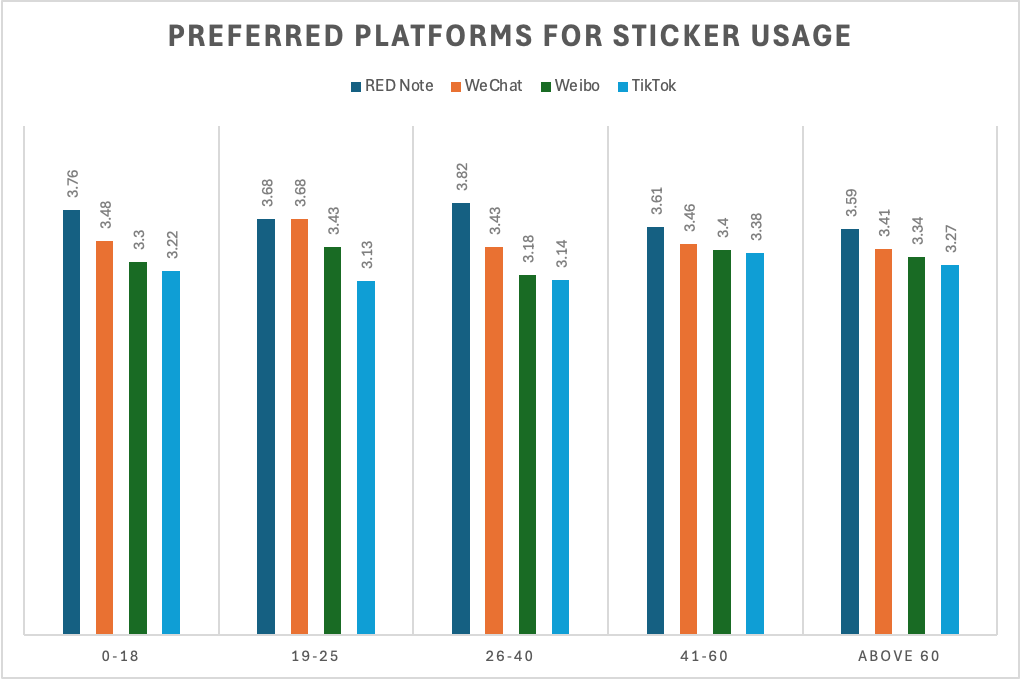

We asked participants to rank their most frequent and preferred platforms of using stickers. The results are shown in the figure above. RED Note is significantly favored for sending stickers, with WeChat being ranked the second preferred platform. However, stickers are less frequently sent in Weibo and TikTok. This is consistent with our hypothesis that the popularity of sticker usage on RED Note and WeChat overwhelms that of Weibo and TikTok. RED Note and WeChat, which are platforms that are primarily social media platforms focused on daily interaction, have abundant sticker sets that are defaulted in the systems, meaning that stickers are highly accessible within these applications. In contrast, Weibo and TikTok are both functional platforms, with the former platform designed for news sharing and the latter one focusing on short video spreading. With limited and often unnoticed sticker sets and low needs for sticker usage, Weibo and TikTok embrace relatively less sticker usage.

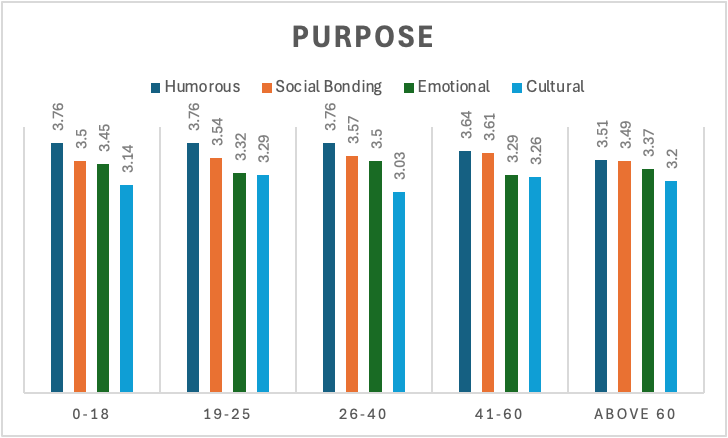

We asked the participants to rank their purposes of using stickers in daily interaction. Among all age groups, the major purpose for sticker usage is to express humor, followed by social bonds, emotions and cultural ideas. Delving into age-specific patterns, social-sticker usage peaks at 3.61 for 41-60 middle-aged-people, indicating the preference of pragmatic use over recreational use of stickers in this particular age group; emotional stickers are most frequently used among 26-40-year-olds, reflecting their needs to relieve from stress brought by different social roles. Cultural stickers are underused in any age group, mainly because of the lack of integration of the newly-introduced means of communication into its connection with a broader social context. Moreover, stickers as a communication tool primarily designed for recreational and informal purposes, are not usually considered a proper tool for spreading culture-related content.

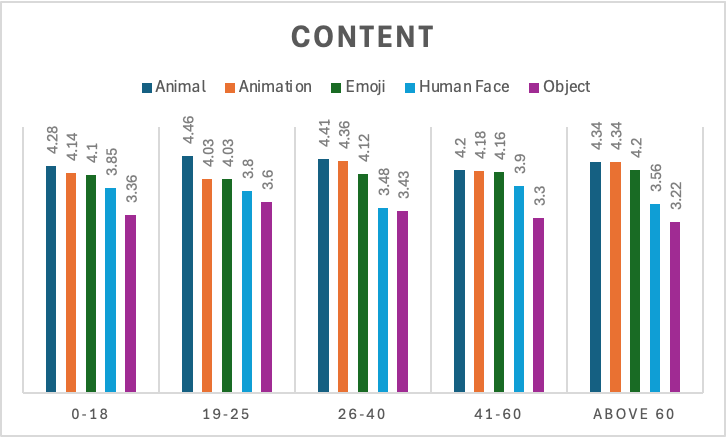

We asked the participants to rank their preferred content of stickers used, including animal-based, animation-based, emoji based, human-face-based, and object-based stickers, in daily interaction. Among all age groups, the most preferred content for sticker usage is animals, followed by animation, human faces, and objects. Investigating age-specific patterns, animation-based stickers’ preference rating peaks at 4.36 for 26-40-year-olds. Dating back to the 1980s and 1990s when people from this group were born and raised, there the rapid emergence of animation series took place. Consequently, people aged 26-40 are more familiar with animation elements, leading to their frequent use of animation-related stickers. The ratings of emoji-based stickers are balanced across different age groups, revealing the preference of simplicity and cross-generational familiarity for all age groups.

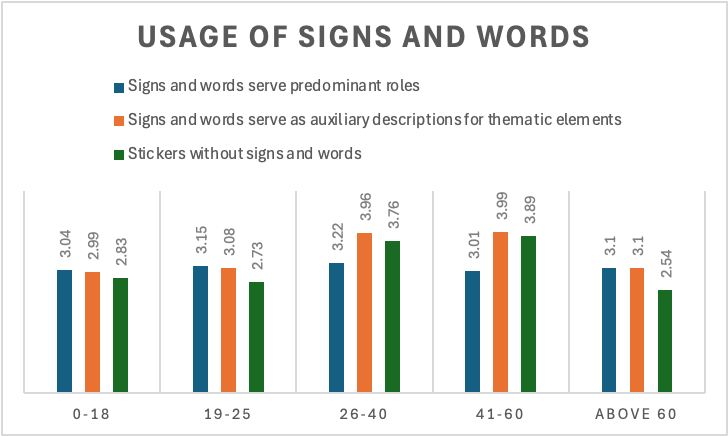

We asked participants to rank their preference for the usage of signs and words in stickers. The three options are: stickers with signs and words serving predominant roles, stickers with signs and words serving as auxiliary descriptions for thematic elements, and stickers without any signs and words. From this chart, we see differing trends in the preferences for signs and words across age groups. For people aged 0-18 and 19-25, they show high preference for signs and words in primary roles and low acceptance of text-free stickers; the preference for auxiliary text stands in the middle. However, for people aged 26-40, 41-60, and above 60, there is a strong reliance on auxiliary text. This might indicate that younger age groups rely heavily on explicit information, hoping to directly convey their ideas and emotions; older age groups, in contrast, send clear messages and are familiar with visual metaphors, reducing the need for further textual explanation.

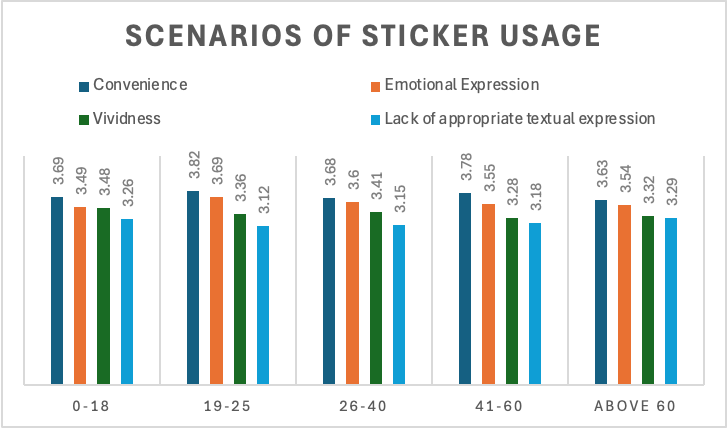

We asked our participants to rank their common scenarios of using stickers as a communication tool to investigate the purpose and intentions of people when deciding to send stickers. The four options are: “I try to make the conversation more simple and convenient” “I want to express my emotions more intensely” “I want to make my expressions more vivid and lively” “Words alone can’t help me fully express my ideas and emotions”. According to the overall feedback, people from all age groups view convenience and emotional expression over vividness, and the least common reason for using stickers is the lack of appropriate textual expression. In particular, young adults aged 19-25 highly value convenience and emotional intensity, and show low reliance on vividness and text substitution, probably attributable to their dependency on communication efficiency and confidence in communication clarity. In contrast, older groups aged 60+ show the lowest emphasis on convenience but the highest reliance on text substitution, revealing their deficiency in textual communication.

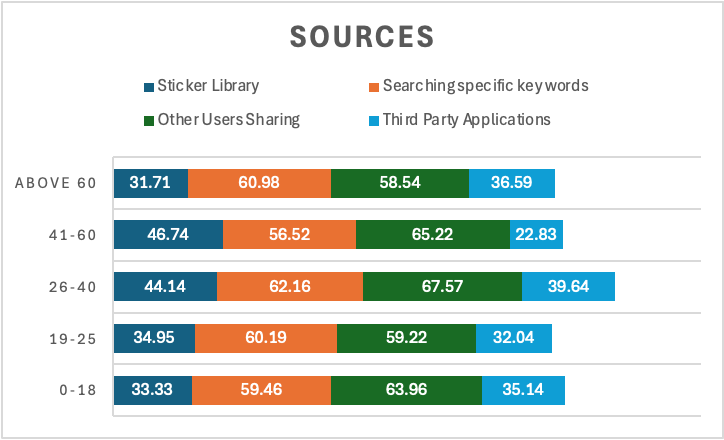

Participants were asked to identify the sources of their stickers used. Across all age groups, the preferred sources of stickers are searching specific key words and saving stickers that others shared. This finding is significant for sticker developers and marketers that they’d better prioritize investment in developing more efficient searching engines for stickers to help users more efficiently acquire and save desired stickers.

5. Discussion

This study set out to investigate the use of stickers on social media across different age groups. Specifically, we asked: What types of stickers do different age groups prefer to use, and how and why do they use stickers? Below we discuss our findings in relation to these questions.

The overall trends of preferred types of stickers used are similar among all age groups, with animal and animation stickers being most favored in terms of content, humorous and social bonding stickers being most popular in terms of purpose, and signs and words serving as crucial components of the stickers.

However, there are still age-specific differences between different age groups. 0-18 year-olds show highest preference for emotional stickers; young adults aged 19-25 have the highest reliance on the convenience of stickers; animation-based stickers are rated highest among middle-aged adults; older groups show lower reliance on predominant text in stickers.

6. Limitations

A limitation of the survey is that we analyzed far more quantitative data than qualitative data due to time constraints. Thus, we weren’t able to determine more personalized preference on the usage of stickers on social media. However, we integrated some qualitative surveys by integrating scenarios into multiple choice surveys to ensure both the efficiency and the accuracy of our survey and results.

Another limitation is that we only included hypothetical reasons behind the preferences of different age groups as we failed to contact respondents for follow-up interviews. However, the reasons stated in our essay are brought after thoughtful consideration and are reliable.

7. Conclusion

Our study of the role of social media in spreading sticker usage across different age groups in China found insightful patterns and differences of user preferences and motivations behind sticker usage. Based on our findings, we proposed possible strategies for sticker developers to expand the exposure of stickers that cater to different age groups’ needs.

For 0-18-year-olds, blending emotional stickers with text overlays can maximize sticker utility; for 19-25-year-old young adults, stickers with simple yet synoptical content are preferred; for middle-aged adults, animation-based stickers with auxiliary texts are optimal; for older adults, simplifying stickers by reducing texts and optimizing sticker discovery paths is crucial.

References

[1]. Li, D. (2017, February 16). Social Media in China: Current Status, Emerging Trends, and More. Annenberg.usc.edu. https: //annenberg.usc.edu/communication/digital-social-media-ms/dsm-today/social-media-china-current-status-emerging-trends

[2]. Tang, Y., & Hew, K. F. (2018). Emoticon, Emoji, and Sticker Use in Computer-Mediated Communications: Understanding Its Communicative Function, Impact, User Behavior, and Motive. New Media for Educational Change, 191–201. https: //doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-8896-4_16

[3]. Susanto, B. S. (2018, July 31). Council Post: the Evolution of Communication and Why Stickers Matter. Forbes. https: //www.forbes.com/sites/forbestechcouncil/2018/07/31/the-evolution-of-communication-and-why-stickers-matter/

[4]. Streets, M. (2023, July 11). The history and evolution of social media explained. WhatIs.com. https: //www.techtarget.com/whatis/feature/The-history-and-evolution-of-social-media-explained

[5]. Prada, M., Rodrigues, D. L., Garrido, M. V., Lopes, D., Cavalheiro, B., & Gaspar, R. (2018). Motives, frequency and attitudes toward emoji and emoticon use. Telematics and Informatics, 35(7), 1925–1934. https: //doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2018.06.005

[6]. Sun, Y., Jia, R., Razzaq, A., & Bao, Q. (2024). Social network platforms and climate change in China: Evidence from TikTok. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 200, 123197. https: //doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2023.123197

[7]. Shifman, L. (2013). Memes in a Digital World: Reconciling with a Conceptual Troublemaker. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 18(3), 362–377. https: //doi.org/10.1111/jcc4.12013

[8]. Mcluhan, M. (1964). The medium is the message. Corte Madera Gingko Press.

[9]. Herring, S., & Dainas, A. (2017, January 4). “Nice Picture Comment!” Graphicons in Facebook Comment Threads. Scholarspace.manoa.hawaii.edu. https: //doi.org/10.24251/HICSS.2017.264

[10]. Tang, L., Omar, S. Z., Bolong, J., & Mohd Zawawi, J. W. (2021). Social Media Use Among Young People in China: A Systematic Literature Review. SAGE Open, 11(2), 215824402110164. https: //doi.org/10.1177/21582440211016421

[11]. Reducing Bias in Self-Reporting Research. (2025). Dnstudio.au; DNStudio. https: //www.dnstudio.au/articles/reducing-bias-in-self-reporting-research

Cite this article

Zhu,Y.;Liu,Y. (2025). The Role of Social Media in Spreading Sticker Usage Across Age Groups in China: Exploring Digital Communication Trends in a Multigenerational Context. Lecture Notes in Education Psychology and Public Media,93,178-185.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of ICEIPI 2025 Symposium: Reimagining Society: AI's Role in Cultural Transformation and Learning Environments

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Li, D. (2017, February 16). Social Media in China: Current Status, Emerging Trends, and More. Annenberg.usc.edu. https: //annenberg.usc.edu/communication/digital-social-media-ms/dsm-today/social-media-china-current-status-emerging-trends

[2]. Tang, Y., & Hew, K. F. (2018). Emoticon, Emoji, and Sticker Use in Computer-Mediated Communications: Understanding Its Communicative Function, Impact, User Behavior, and Motive. New Media for Educational Change, 191–201. https: //doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-8896-4_16

[3]. Susanto, B. S. (2018, July 31). Council Post: the Evolution of Communication and Why Stickers Matter. Forbes. https: //www.forbes.com/sites/forbestechcouncil/2018/07/31/the-evolution-of-communication-and-why-stickers-matter/

[4]. Streets, M. (2023, July 11). The history and evolution of social media explained. WhatIs.com. https: //www.techtarget.com/whatis/feature/The-history-and-evolution-of-social-media-explained

[5]. Prada, M., Rodrigues, D. L., Garrido, M. V., Lopes, D., Cavalheiro, B., & Gaspar, R. (2018). Motives, frequency and attitudes toward emoji and emoticon use. Telematics and Informatics, 35(7), 1925–1934. https: //doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2018.06.005

[6]. Sun, Y., Jia, R., Razzaq, A., & Bao, Q. (2024). Social network platforms and climate change in China: Evidence from TikTok. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 200, 123197. https: //doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2023.123197

[7]. Shifman, L. (2013). Memes in a Digital World: Reconciling with a Conceptual Troublemaker. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 18(3), 362–377. https: //doi.org/10.1111/jcc4.12013

[8]. Mcluhan, M. (1964). The medium is the message. Corte Madera Gingko Press.

[9]. Herring, S., & Dainas, A. (2017, January 4). “Nice Picture Comment!” Graphicons in Facebook Comment Threads. Scholarspace.manoa.hawaii.edu. https: //doi.org/10.24251/HICSS.2017.264

[10]. Tang, L., Omar, S. Z., Bolong, J., & Mohd Zawawi, J. W. (2021). Social Media Use Among Young People in China: A Systematic Literature Review. SAGE Open, 11(2), 215824402110164. https: //doi.org/10.1177/21582440211016421

[11]. Reducing Bias in Self-Reporting Research. (2025). Dnstudio.au; DNStudio. https: //www.dnstudio.au/articles/reducing-bias-in-self-reporting-research