1. Introduction

Emotion, a state of mind that we experience throughout daily life, remains ambiguous in the sense that it contrasts between individuals. Various factors can influence the state of mind, for example biological, cultural, and social role differences among gender. Biologically, one element in which women perceive emotion differently than men is in the case of the menstrual cycle. Researchers Dan, et al. found that men’s neural activity increased when they experience negative emotions while the activity of females’ right cerebellum increased during the menstrual phase [1]. Besides biological factors, the emotions among males and females are inconsistent and distinctive cross-culturally [2]. In regards to social roles, men and women both experience positive emotions at different times of their lives but the style of their experiences is different, compared with men, women’s positive emotions were more related to their social interaction with friends, and family [3].

In addition to these idiosyncrasies, men and women experience distinctive emotions under different conditions [4, 5]. Regarding positive emotions, women are more likely to experience compassion than men, in contrast, men are more likely to have pride than women [3]. According to past research [4], we know that gender differences in self-conscious emotions (SCE) such as guilt, shame, pride, and embarrassment exist, showing that females tend to experience more negative emotions while males experience more pride. A previous study has suggested that males are more likely to experience positive emotions and females are more likely to have negative emotions when experiencing immoral behaviors, for instance, women expected lower positive emotions and higher self-conscious moral emotions when conducting immoral behaviors compared to men [5].

Women and men also express different emotions while reading. Although both men and women are highly similar when reading the experience texts, they show different emotional affinities towards plots and characters when reading action texts [6]. This gave us an idea of how entertainment and media affect the emotions of both women and men differently, therefore, we used videos as emotional triggers in the current study.

While the past studies are general and broad, in our work, we wanted to narrow down to how negative emotions affect both genders. In general, our study will examine how anger and sadness are self-perceived differently in males or females under the same situation. We are interested in the specific negative emotions: sadness and anger, and the different degree of the two emotions between males and females when expose to a trigger. Accordingly, the hypothesis of the present study was that females are more sensitive to sadness while males are more sensitive to anger. Specifically, males will score higher on anger compared with females when exposed to an infuriating video, indicating that males tend to experience more anger than females do under infuriating situations. In contrast, females will score higher in the degree of sadness compared to males after watching a sad video, indicating that females tend to experience more sadness than males do under dismal circumstances.

2. Present Work

In the present study, we will examine how anger and sadness are self-perceived differently in males or females under the same situation. The study specifically approaches sadness and anger. We expect that females would rate higher levels of sadness and males would rate higher levels of anger after watching the triggering videos.

3. Experiment Method

We will report all measures, manipulations, and exclusions. This study will be approved by and carry out in accordance with the recommendations of the Institutional Review Board for human participants with written informed consent obtained from all participants.

3.1. Participants.

450 individuals will participate in the study initially, 30 will be excluded because the participants identified themselves other than cisgender, or under 18 without parental consent, or emotionally unstable at the moment. The remaining 420 participants participate in the study.

Our primary hypothesis involves assessing the levels of emotional rating among genders when expose to emotional triggers. In order to have a strong database, we used G Power [7] to calculate our sample size. Assuming an effect size Cohen’s d = 0.5, the sample size was 210 participants in each condition (105 females and 105 males) and the total is 420 participants to achieve a 95% statistical power. While there are 210 participants in each video group, 105 females and 105 females were randomly assign to each of the two conditions. We plan to collect data from about 450 participants in case of any data that cannot be used.

3.2. Procedure.

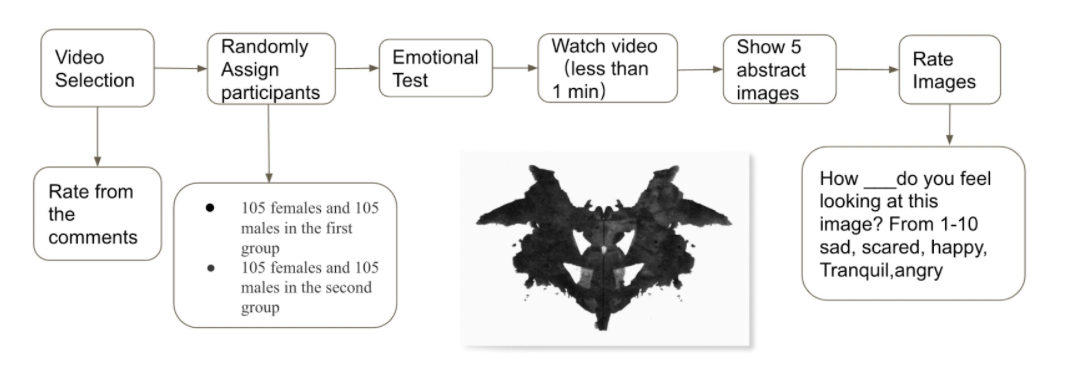

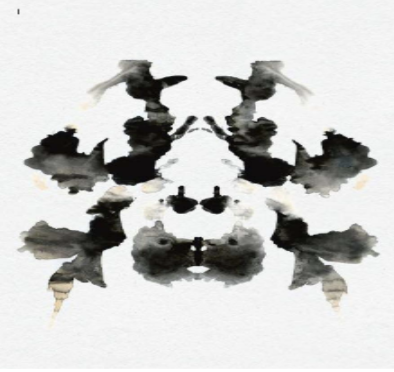

In the present study, we will performe a video comment selection, analyzing the comments under the videos and choosing the best fit of each condition. In our process(see Figure 1), we will choose two videos under one minute. If more than 90% of the comment section under the video indicate the video as a sad video, the video would be chosen as our sad video sample in the study. The same process will br used to select the infuriating video sample. After selecting the video samples, participants will be randomly assigned to watch either one of the two short videos (one is about sadness and the other is about anger). Before playing the video, we will perform an emotional test in order to examine the emotional status of the participants at the moment and eliminate participants with unstable emotions. We also will ask the participants to identify their gender at the beginning of the test, ensuring the testing data will only include male and female identifying subjects. The procedure of watching the video will be administered to trigger the target emotion of participants, and then we will use implicit emotion assessment to measure the emotional level of our participants after watching the videos. The videos act as emotional triggers which will affect an individual's emotional judgment toward the images. Since participants won’t know that their feelings towards the following pictures would be influenced by the video, it is an extremely good way of blinding them. First, we will show each individual five Rorschach inkblot test images and then asked one question for each image as shown in Figure 2. In the first image, we asked “On a scale from 1 to 10, how sad do you feel looking at this image?” For the second image, we asked “On a scale from 1 to 10, how scared do you feel looking at this image?” In the third image, we asked “On a scale from 1 to 10, how happy do you feel looking at this image?” In the fourth image, we asked “On a scale from 1 to 10, how tranquil do you feel looking at this image?” In the final image, we asked “On a scale from 1 to 10, how angry do you feel looking at this image?” This implicit emotions assessment was modeled by researchers Bartoszek and Cervone’s study which proved this method of assessing the ratings of abstract images revealing distinct emotional states is valid.

On a scale from 1 to 10, how tranquil do you feel looking at this image?

Figure 1: The process of the current study.

Figure 2: Example one of Rorschach inkblot test images.

3.3. Measure

The design of the current study will be a 2 (gender: male or female) x 2 (emotions: sadness and anger) factorial test, all between subject design. Two independent samples T-tests will be conducted to examine the emotional differences between female and male groups under each condition (anger and sadness). For each condition, the mean score of males and females will becompared, and then the mean difference will be calculated to obtain the t value and the p-value(see Figure 3). This will help determine whether there exists a significant difference between the means of the two gender groups. We will run the data in Excel to analyze.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive statistics.

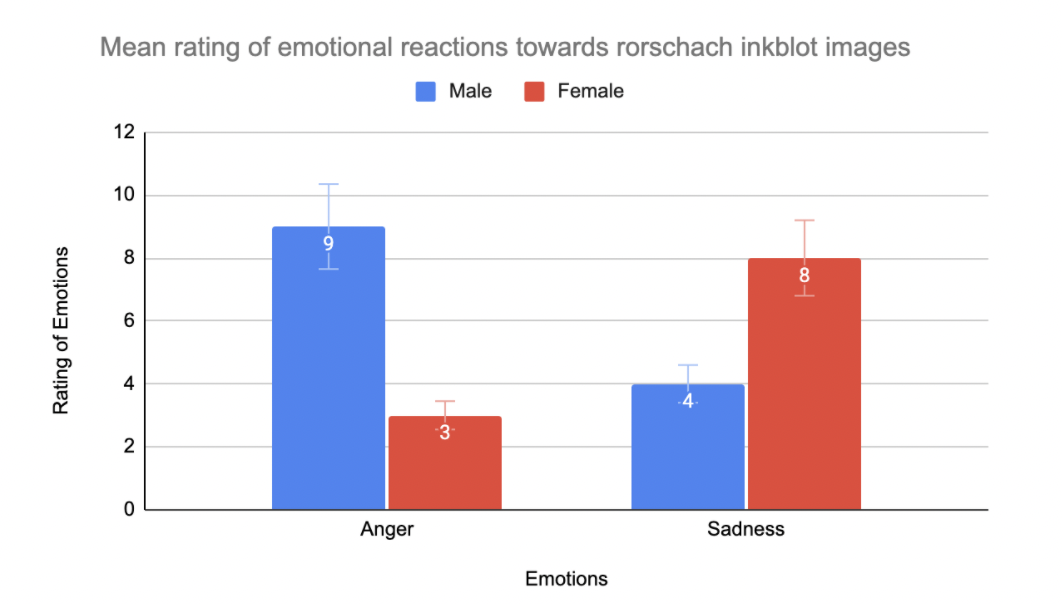

Aim 1. A two-tailed independent t-test will show that the levels of anger in males(M=9, SD=1.32) are significantly higher than females (M=3, SD=1.06) when expose to infuriating video; t(104)=9.24, p<0.001.

A two-tailed independent t-test shows that females(M=8, SD=1.08) will rate significantly higher levels of sadness than men(M=4, SD=1.22) when expose to sad video; t(104)=7.43, p<0.001.

The result of the study will support our hypothesis that women experience higher sadness than men toward sad circumstances, in contrast, men experience more anger than women toward infuriating circumstances

Figure 3: Males reported higher levels of anger regarding the infuriating video while females reported higher levels of sadness regarding the sad video. According to the graph, the mean rating of males scored 5 points higher on anger than females after watching the infuriating video, and females rated 4 points higher on sadness than males after watching the sad video.

5. Conclusion

In the present study, the goal is to examine how negative emotions affect both genders. In general, our study will examine how anger and sadness are self-perceived differently in males or females under the same situation. We will be focused on the two specific negative emotions: sadness and anger. We will show two videos, one related to sadness and the other related to anger. Afterward, we will provide five abstract images to participants for them to rate their emotional reactions toward the images. The assessment we will be done, is supported by a previous study [8]. We will find that females rated higher levels of sadness than males when expose to sad content; in contrast, the males rated higher levels of anger when expose to infuriating content. This finding is consistent with our hypothesis that males tend to experience more anger than females do under infuriating situations, and females tend to experience more sadness than males do under dismal circumstances. Unlike most previous studies, this study will only pinpoint two important and specific emotions and examined how these two emotions differ among gender.

The limitation of the study is that the sample size is general and wide, since we won’t account for different emotional patterns across culture or age. However, age and culture could be two significant moderators between emotional difference and gender. For future studies, we suggest researchers can focus on how culture and age moderate the emotional differences between genders. Moreover, the procedure of the current study will be to use video to evoke participants’ state of mind. Future studies could expand on this and use text, or images as emotional triggers to manage individuals’ emotions.

References

[1]. Dan, R., Canetti, L., Keadan, T., Segman, R., Weinstock, M., Bonne, O., Reuveni, I., & Goelman, G. (2019) Sex differences during emotion processing are dependent on the menstrual cycle phase. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 100, 85–95.

[2]. Gong, X., Wong, N., & Wang, D. (2018) Are gender differences in emotion culturally universal? Comparison of emotional intensity between Chinese and German samples. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 49(6), 993–1005.

[3]. Shamim, A., & Muazzam, A. (2018) Gender Differences in Positive Emotion. Journal of Arts & Social Sciences, 5(1), 125–137.

[4]. Allison, C., Else-Quest, N. M., Higgins, A., & Morton, L. C.(2012). Gender Differences in Self-Conscious Emotional Experience: A Meta-Analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 138(5), 947–981.

[5]. Ward, S. J., & King, L. A. (2018) Gender differences in emotion explain women’s lower immoral intentions and harsher moral condemnation. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 44(5), 653–669.

[6]. Odağ, Ö. (2013) Emotional engagement during literary reception: Do men and women differ? Cognition & Emotion, 27(5), 856–874.

[7]. Erdfelder, E., Faul, F. & Buchner (1996) A. GPOWER: A general power analysis program. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers, 28, 1–11.

[8]. Bartoszek, & Cervone, D. (2017) Toward an implicit measure of emotions: ratings of abstract images reveal distinct emotional states. Cognition and Emotion, 31(7), 1377–1391.

Cite this article

Wang,Z. (2023). Differences in Self-perceiving Emotions: The Role of Gender. Lecture Notes in Education Psychology and Public Media,2,169-173.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Educational Innovation and Philosophical Inquiries (ICEIPI 2022), Part I

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Dan, R., Canetti, L., Keadan, T., Segman, R., Weinstock, M., Bonne, O., Reuveni, I., & Goelman, G. (2019) Sex differences during emotion processing are dependent on the menstrual cycle phase. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 100, 85–95.

[2]. Gong, X., Wong, N., & Wang, D. (2018) Are gender differences in emotion culturally universal? Comparison of emotional intensity between Chinese and German samples. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 49(6), 993–1005.

[3]. Shamim, A., & Muazzam, A. (2018) Gender Differences in Positive Emotion. Journal of Arts & Social Sciences, 5(1), 125–137.

[4]. Allison, C., Else-Quest, N. M., Higgins, A., & Morton, L. C.(2012). Gender Differences in Self-Conscious Emotional Experience: A Meta-Analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 138(5), 947–981.

[5]. Ward, S. J., & King, L. A. (2018) Gender differences in emotion explain women’s lower immoral intentions and harsher moral condemnation. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 44(5), 653–669.

[6]. Odağ, Ö. (2013) Emotional engagement during literary reception: Do men and women differ? Cognition & Emotion, 27(5), 856–874.

[7]. Erdfelder, E., Faul, F. & Buchner (1996) A. GPOWER: A general power analysis program. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers, 28, 1–11.

[8]. Bartoszek, & Cervone, D. (2017) Toward an implicit measure of emotions: ratings of abstract images reveal distinct emotional states. Cognition and Emotion, 31(7), 1377–1391.